Kashmir

In the North-Eastern part of Kashmir, India was concerned about the safety of her lines of communication with Ladakh. Pakistani picquets in the Kargil area overlooked the Srinagar-Leh road. Infiltration routes from the direction of Gilgit and Skardu were also a cause for worry. The defence of this region was the responsibility of 3 Division, commanded by Major General S.P. Malhotra. An overwhelming portion of his strength faced the Chinese.

The threat from Gilgit and Skardu was eliminated by the Ladakh Scouts, under Major Rinchen, MVC. The operation began on 6 December with a bold advance up the Shyok Valley. Rinchen made good progress initially and took Turtok. This meant an advance of 22 kilometres in very bad weather, with temperatures dipping to –25 degrees Celsius. The average altitude of the posts captured by the Ladakh Scouts was 5,000 metres and their achievement was remarkable. However, the problem of resupply made further progress almost impossible.

Click to buy: Indian Army After Independence

The Pakistanis now began their old game of interfering with movement between Dras, Kargil and Leh. 121 Infantry Brigade, commanded by Brigadier M.L. Whig, was ordered to deal with the situation.

The average altitude of the posts captured by the Ladakh Scouts was 5,000 metres and their achievement was remarkable.

The offending picquets were at altitudes averaging 4,500 metres and weather conditions were hardly better than in the Shyok Valley. Also, the Pakistanis had strengthened these since 1965. Whig, however, took up the challenge and mounted a vigorous offensive on both sides of the Shingo River, There was tough resistance by the enemy which was able to bring down mortar and machine-gun fire on the attackers. All the same, the brigade captured 36 out of a total of 80 enemy posts in the area. The territory gained was about 110 square kilometres.

The captured area in the Shyok Valley and in Kargil was later retained by India under the Simla Agreement. The gains in the Kargil area gave significant advantage to India. The cost, however, was heavy. There were 517 cases of frostbite, while battle casualties were 278 (55 killed, 195 wounded and 28 missing). The enemy lost 22 as prisoners, and its casualties in dead were estimated at 114.

The defence of the CFL in the rest of Kashmir, excluding the Punch sector, was the responsibility of 19 Infantry Division under Major General E. D’Souza. Anticipating that Pakistan might send guerrilla-type forces into this region, as in 1965, Indian authorities took adequate precautions. The division was freed of the responsibility for internal security by raising a temporary organization, called ‘V’ Sector. Pakistan, however, had learnt a lesson in previous ventures and did not repeat the tactic.

D’Souza’s brief was confined to limited offensive operations which would improve the division’s defesive posture. Both India and Pakistan had over the years strengthened their defences on the CFL to such an extent that it was difficult and costly to launch frontal assaults. The mountainous terrain also gained by 19 Division was largely due to the Pakistani command, having withdrawn some of its regular troops for its Punch offensive.

| Editor’s Pick |

Of the three operations mounted by the division soon after the outbreak of hostilities, only one succeeded. This was the capture of two features by 8 Rajputana Rifles in the Lipa Valley, between the Tithwal and Uri sectors. D’Souza exploited the success by pushing further into the valley and occupying the entire Kaiyan bowl.

These operations entailed much administrative effort and the troops undertaking them had to undergo considerable hardship. When the cease-fire came into effect, they settled down to winter conditions and snow covered the area. With the melting of the snows, a small Pakistani detachment surfaced near Kaiyan. The enemy had maintained it during the winter months through a track that ran along a nulla, both sides of which were held by Indian troops. The divisional commander had known of the existence of the pocket but had not reported it to the higher authorities on the assumption that he could get rid of it any time.

Of the three operations mounted by the division soon after the outbreak of hostilities, only one succeeded.

However, when he tried to negotiate with the Pakistanis for its removal, they refused.8 He then mounted a hasty attack which failed. The Pakistani command taking advantage of the situation, quickly brought up more troops and threw back 9 Sikh, the forward Indian battalion. The episode earned a good deal of criticism for Major General D’Souza.

11 Corps

Coming South of the CFL into the Punjab plains, past the Shakargarh Bulge, we reach the area of 11 Corps, commanded by Lieutenant General N.C. Rawlley. Headquarters 11 Corps had Number 1 Tactical Air Centre affiliated to it. Extending from Dera Baba Nanak to the Sutlej and beyond, up to Anupgarh, the area of 11 Corps had seen bitterly fought battles in 1965. This time, there were only local actions, though Some of them were contested enough to be considered battles. A major difference in the scenario, as compared to 1965, was a ditch-cum-bund line that now formed India’s forward defence in some sensitive areas. The defence line was a few kilometres behind the international frontier and the intervening ground was held by the BSF and covering troops. While it provides a safeguard against surprise attack, this type of linear defence entails initial loss of territory unless the ground ahead of it is dominated all along from the bund. This, however, ties down troops and equipment and may not leave adequate reserves to deal with a breakthrough. Some of the losses suffered by 11 Corps were due to this inherent weakness in the system.

From the course of events, it would appear that 11 Corps’ operational plans envisaged the evacuation of border posts when under attack. The premise apparently was that they would be recaptured with a riposte after the pattern of enemy plans had been evaluated. However, once the enemy had secured a lodgement, it became difficult to push it out. In the area between the Ravi and the Sutlej, the struggle to recapture some of the lost posts continued till the cease-fire.

Though enemy strength on the enclave turned out to be just about a company, the riverine terrain posed many difficulties for the operation, which was mounted on the evening of 5 December.

As in 1965, both sides went for each other’s enclaves on these two rivers. These bits of land were a legacy of the partition. Surrounded by alien tenitory, they were at the mercy of the other side. But they had tactical value: an enclave in enemy area was a launching pad for attack by the holding side.

15 Infantry Division

There were two enclaves near Dera Baba Nanak, one Indian and the other Pakistani. The Indian enclave of Kasowal was North of the Ravi and the Pakistani enclave of Jassar (Dera Baba Nanak Enclave to the Indians) was South of the river. The Jassar Enclave was linked to Pakistan’s hinterland by a rail-cum-road bridge. It had been fortified with pill-boxes and bunkers built on the irrigation bunds. The area was marshy and tall elephant sarkanda grass obscured observation. Facing the enclave was 86 Infantry Brigade, commanded by Brigadier (later Lieutenant General) Gowri Shankar. This brigade was one of five under 15 Division commanded by Major General B.M. Bhattacharjea. The five brigades were as follows:

- 86 Infantry Brigade with 71 Armoured Regiment (T-55) under command from Dera Baba Nanak to Gill Ferry on the Ravi.

- 54 Infantry Brigade South of Gill Ferry and inclusive of the Ranian axis to Grand Trunk Road (exclusive).

- 66 Infantry Brigade from the Grand Trunk Road to the Rajatal approach.

- 96 Infantry Brigade was deployed to give a bit of depth to the main approach to the Chagawan area.

- The fifth brigade, 11 Corps ‘reserve’, was actually a formation from 14 Infantry Division in the Ajnala area. 15 Division had 66 Armoured Regiment (Vijayantas) as its integral regiment.

Pakistani infantry and tanks attacked Kasowal enclave around 2130 hours on 3 December and its garrison vacated it before the morning. The next day, preparation began for the capture of the Dera Baba Nanak/Jassar Enclave. Gowri Shankar had under him one regiment of armour and an independent artillery brigade (seven fire units) besides his infantry brigade. Though enemy strength on the enclave turned out to be just about a company, the riverine terrain posed many difficulties for the operation, which was mounted on the evening of 5 December. When his armour bogged on a steep bund, Gowri Shankar quickly changed the direction of attack by sending the follow-up battalion from the enemy’s rear. This put the Pakistanis into panic and the enclave was in Indian hands by next morning. To make sure that the enemy should not use the bridge; one span on the home side was destroyed.

Another enclave over which the two sides fought was around the villages of Fatehpur and Bhago Khama. This was a readymade launch-pad for Pakistan for an advance towards Amritsar from the Nonh-West. It would have been more expedient for 15 Division to eliminate it right at the beginning but Bhattacharjea chose to block it with a containing position, held by elements from 96 Infantry Brigade. The enemy struck the first blow by capturing a bund and some villages to extend this enclave. Thereafter attacks and counter-attacks continued. The Pakistanis had no armour supporting their infantry here and suffered heavily in casualties and equipment. They also suffered a moral setback on 5 December, when about 150 men of the East Bengal Rifles surrendered to Indian troops in this area.

Another enclave over which the two sides fought was around the villages of Fatehpur and Bhago Khama. This was a readymade launch-pad for Pakistan for an advance towards Amritsar from the Nonh-West. It would have been more expedient for 15 Division to eliminate it right at the beginning but Bhattacharjea chose to block it with a containing position, held by elements from 96 Infantry Brigade. The enemy struck the first blow by capturing a bund and some villages to extend this enclave. Thereafter attacks and counter-attacks continued. The Pakistanis had no armour supporting their infantry here and suffered heavily in casualties and equipment. They also suffered a moral setback on 5 December, when about 150 men of the East Bengal Rifles surrendered to Indian troops in this area.

7 and 14 Infantry Divisions

South of the GT Road, the Khalra-Khem Karan-Ferozepur border was the responsibility of 7 Infantry Division, commanded by Major General Freemantle. In the Khalra area, the main Indian defence line was East of the UBD Canal, several kilometres East of the border. Covering troops ahead of the canal withdrew after the enemy’s initial assault on the evening of 3 December. Thereafter the Pakistanis advanced swiftly and were soon leaning on the canal and threatening Khalra itself. Attempts to throw them back proved fruitless, though 14 Rajput made a valiant bid to recapture Chhina Bidhichand, a village North of Khalra.

The enemy did not, however, try to come further East. Pakistan’s Sehjra Bulge, South of Khem Karan, is of tactical importance to India. Its capture lends depth to the defences of Khem Karan and some security to her enclave at Hussainiwala, lying South of the bulge. In 1965, a company of Indian infantry and a detachment of armed police had taken Sehjra without much difficulty initially. But Pakistan had since strengthened its defences. This time a brigade attack by 48 Infantry Brigade was put in on the night of 5 December and the Pakistanis yielded the position after a stiff fight, in which they lost about 30 men killed and 65 taken prisoner.

“¦the Pakistanis advanced swiftly and were soon leaning on the canal and threatening Khalra itself.

Had this operation been launched two days earlier it might have saved the Hussainiwala Enclave. The Hussainiwala complex, near Ferozepur, comprises the bridge over the Sutlej, the Gang Canal headworks and some territory across the river. A memorial to the great freedom-fighter Bhagat Singh also stood on this territory, giving it sentimental value. The whole complex was held by 15 Punjab and the BSF. The battalion was part of a peculiar command system that prevailed at the time. It belonged to a brigade of 7 Division, but had been placed under 35 Brigade of 14 Division which was then under 7 Division.

The enclave had strong defences and the battalion had a fine operational record. However, the Pakistani attack; launched soon, after dusk on 3 December, took the Punjabis by complete surprise. Most of their officers and JCOs had assembled during the afternoon at battalion Headquarters for a farewell tea-party to their subedar major, who was retiring from service. The Headquarters was South of the river and the party was still on when the attack came. The enemy had pin-pointed its initial objectives and some of them were already in its hands before the command group could come to grips with the situation.9

The companies manning the defences fought hard but faced superior numbers. The enemy attacked with two battalions ex 106 Infantry Brigade, supported by a squadron of armour. The battalion commander despatched a troop of tanks to reinforce his beleaguered troops. However, in the confusion of battle, the bridge, which had been prepared for demolition, was blown through panicky action while one tank was still on the far end, dropping a span. The withdrawing Centurion, carrying a number of wounded, fell into the river. Fighting continued till late in the night, with the remnants of the forward companies valiantly trying to hold on to what remained in their hands. Their radio communication with battalion Headquarters had broken down but the battalion commander made no effort go forward and see things for himself.

“¦the Indian Air Force attacked enemy troops several times and the artillery pounded them continuously.

The next morning, the Indian Air Force attacked enemy troops several times and the artillery pounded them continuously. The Punjabis had suffered heavy casualties, mainly in missing men but they still had a good deal of fight left in them. Instead of reinforcing them, however, the brigade commander recommended a withdrawal. The divisional commander was too far away to leave his Headquarters at Patti. The corps commander could also not come to see things for himself as his helicopter had developed a mechanical fault. He accepted the brigade commander’s recommendation and Hussainiwala was abandoned that night.

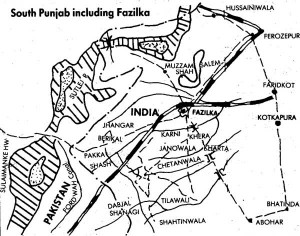

Pakistan’s 2 Corps and her GHQ reserve in the Multan-Okara-Montgomery area were cause for worry to the Indian high command. It was considered likely that the enemy would use these forces for an advance across the Sutlej between Ferozepur and Fazilka, or in the desert region between Fazilka and Anupgarh. Prisoners of war and other sources later confirmed that Pakistan did have plans to launch a major offensive into the Ganganagar region, but these were not put into effect for various reasons.10 It was to counter this threat that Army Headquarters positioned its 1 Armoured Division, commanded by Major General Gurbachan Singh, and 14 Infantry Division under Major General Harish Bakhshi, in the Muktsar-Kot Kapura-Faridkot area. However, 14 Division was weakened before the start of hostilities by the transfer of one of its infantry brigades to Ajnala, under 15 Division. Of its remairiing strength, 35 Infantry Brigade was placed under 7 Division. This brigade, however, reverted to 14 Division after the loss of Hussainiwala. With two brigades now under him, Bakhshi was made responsible for the area from the Harike headworks upto Fazilka, the city of Ferozepur being one of his defensive commitments.

Bakhshi did not stay long with 14 Division. On the night of 4/5 December the BSF vacated two posts, Joginder and Raja Mahatam, after they were subjected to heavy shelling. Joginder was recaptured without difficulty but the Pakistanis holding Raja Mahatam showed more spirit. After the latter’s recapture, Bakhshi was wounded by a mine-blast when he visited the post, and was later evacuated.

| Editor’s Pick |

The new GOC was Major General Onkar Singh Kalkat. He infused a new spirit into his command and showed the aggressiveness essential to offensive defence. He decided to use the forward troops of 35 Brigade to push back some of the enemy border posts opposite Ferozepur. Basti and New Kasoke, North of Ferozepur, were captured by 15 Dogra on the night of 6/7 December. Soon after, it was decided to clear the Pakistani enclave opposite Mamdot. As part of this operation, 15 Dogra took Rangewala at heavy cost and later followed up by seizing Jaluke Dhuan and Amrud Wali. Another battalion, 13 Punjab, captured Dona Beta, Pira Kana and Jaloke Hithar.

Furthet South, 116 Brigade was deployed to hold two axes: Ferozepur-Guru Harsarai and Muktsar-Jalalabad. In the absence of any move by the enemy, Kalkat ordered the capture of certain border posts to improve his posture. As a result, Pireke, Gatti Bharola, Kali Sahu, Ghurka and Amin Bhaini were added to the division’s bag. These posts were mostly taken, by smart manoeuvre, at small cost. After the cease-fire, the enemy tried to recapture Kali Sahu on 3 January but the attempt was foiled with heavy losses to the enemy.

After the experience of 1965, India had put up a wet ditch-cum-bund for the protection of Fazilka.

From Fazilka to Anupgarh the border was placed under an ad hoc division-sized formation, called ‘F’ Sector. Raised in July 1971, under Major General Ram Singh, it had its Headquarters at Abohar. He had three infantry brigades under him and a complement of other arms, these being 166 Field Regiment, 18 Cavalry less a squadron (T-54), one independent squadron (Sherman), four 130-mm medium batteries, a parachute field regiment and an engineer brigade equivalent. The enemy had two independent infantry brigades facing the sector: 105 at Sulaimanke and 25 at Bahawalnagar. The main threat, however, was from the forces held further back, which we have mentioned earlier.

Though Pakistan did not launch these reserves, her Sulaimanke brigade mounted a local action against Fazilka. Its aim was to bolster the defences of the Sulaimanke headworks, situated only about 1,500 metres from Indian territory. After the experience of 1965, India had put up a wet ditch-cum-bund for the protection of Fazilka. The Sabuna distributary, as it was called ran parallel to the border and about four to five kilometres from it. A few strongpoints had also been developed ahead of the distributary. The case was the same for the Pakistanis as for the Indians at Hussainiwala, except that the Sulaimanke Enclave did not have a continuous river obstacle to its rear.

The defence of Fazilka was assigned to 67 Infantry Brigade, under Brigadier S.S. Chowdhary. Chowdhary had under him three infantry battalions (4 Jat, 15 Rajput and 3 Assam), approximately two battalions of BSF, two squadrons of armour (‘B’ Squadron, 18 Cavalry [T-54] and 4 Independent Armoured Squadron [Scinde Horse]), 166 Field Regiment and a medium battery. His orders were to contain the Sulaimanke position and defend Fazilka (see Eig. 14.4). Like other border towns in ‘F’ Sector, Fazilka had been turned into a fortress. Chowdhary deployed most of 4 Jat and 15 Rajput for its close defence, while 3 Assam held the Sabuna distributary and the strongpoints ahead of it. The BSF manned the border posts.

A basic weakness in the brigade’s deployment was that the positions on the distributary, the strongpoints and the fortress did not form an integrated network of defences. Fazilka town was almost ten kilometres from the distributary. The brigade commander had further unbalanced himself by deploying three companies of 3 Assam on the strongpoints, while the distributary itself was held by a weak company and some battalion Headquarter personnel. The disposition implied firstly that the strong points would be held against enemy attack till a counter-stroke was delivered to relieve them. Unfortunately, most of them were abandoned on first contact. Secondly, troops in the strongpoints ahead, which had to fall back on the distributary or hold on till another unit could man the obstacle, again by implication, did not do so.When the first shots were fired on the evening of 3 December one of the strongpoints came under attack. Chowdhary ordered its garrison to fall back, leaving a small number of men to maintain contact with the enemy. The locality fell soon after and the enemy followed up with an attack on the distributary itself. By 2030 hours, a considerable portion of it had fallen, together with a bridge near the village of Beriwala.

A basic weakness in the brigade’s deployment was that the positions on the distributary, the strongpoints and the fortress did not form an integrated network of defences. Fazilka town was almost ten kilometres from the distributary. The brigade commander had further unbalanced himself by deploying three companies of 3 Assam on the strongpoints, while the distributary itself was held by a weak company and some battalion Headquarter personnel. The disposition implied firstly that the strong points would be held against enemy attack till a counter-stroke was delivered to relieve them. Unfortunately, most of them were abandoned on first contact. Secondly, troops in the strongpoints ahead, which had to fall back on the distributary or hold on till another unit could man the obstacle, again by implication, did not do so.When the first shots were fired on the evening of 3 December one of the strongpoints came under attack. Chowdhary ordered its garrison to fall back, leaving a small number of men to maintain contact with the enemy. The locality fell soon after and the enemy followed up with an attack on the distributary itself. By 2030 hours, a considerable portion of it had fallen, together with a bridge near the village of Beriwala.

Chowdhary now ordered a company of 4 Jat and a squadron (less two troops) of armour to clear the enemy from the distributary. Some of the tanks, however, got bogged before reaching the objective and some others were destroyed by enemy action. It was still touch and go for the weak company of 6 Frontier Force on the Sabuna. As the tanks closed up the men started falling back. The company officer tried his hand with a strim anti-tank grenade and a T-54 caught fire. The men rallied bravely. 6 Frontier Force was thereafter able to reinforce the captured segment with recoilless and machine guns.

4 Jat was able to clear only a portion of the distributary and the bridge remained in enemy hands. During the night, many of the BSF posts fell or were withdrawn. The same was the fate of the remaining strongpoints held by 3 Assam and by first light, most of the battalion had withdrawn towards the distributary after suffering casualties. Less than half a dozen posts West of the distributary remained in Indian hands. Perhaps the most unfortunate happening was the blowing-up, in the early hours of 4 December of more than 20 bridges on the distributary and the creek from which it took off.Another counter-attack against the Beriwala lodgement was launched by 4 Jat during the night of 4/5 December but it achieved only partial success. The foothold was strengthened the next day and a third counter-attack was put in during the night of 5/6 December by the same battalion. In a determined bid, the forward elements reached the objective but in the ensuing hand-to-hand fighting, the company commander was killed. Some of the troops held on to a portion of the objective while the rest fell back. 4 Jat lost more than 60 men in this action.

4 Jat was able to clear only a portion of the distributary and the bridge remained in enemy hands. During the night, many of the BSF posts fell or were withdrawn. The same was the fate of the remaining strongpoints held by 3 Assam and by first light, most of the battalion had withdrawn towards the distributary after suffering casualties. Less than half a dozen posts West of the distributary remained in Indian hands. Perhaps the most unfortunate happening was the blowing-up, in the early hours of 4 December of more than 20 bridges on the distributary and the creek from which it took off.Another counter-attack against the Beriwala lodgement was launched by 4 Jat during the night of 4/5 December but it achieved only partial success. The foothold was strengthened the next day and a third counter-attack was put in during the night of 5/6 December by the same battalion. In a determined bid, the forward elements reached the objective but in the ensuing hand-to-hand fighting, the company commander was killed. Some of the troops held on to a portion of the objective while the rest fell back. 4 Jat lost more than 60 men in this action.

At this stage, Ram Singh took charge of the battle. He reinforced the brigade with infantry and artillery and also replaced one armour squadron as casualties and bogging had reduced its strength to a troop. Then, on the night of 8/9 December he ordered another counter-attack by 15 Rajput and a squadron of tanks to retake Beriwala. However, the Pakistanis were by this time well entrenched and threw back the attack. Ram Singh was wounded, but retained command.

Ram Singh took charge of the battle. He reinforced the brigade with infantry and artillery and also replaced one armour squadron as casualties and bogging had reduced its strength to a troop.

Repeated failures led to Chowdhary’s replacement by Brigadier Piara Singh on 11 December. Meanwhile, the enemy had become more aggressive. It attacked a position on the outskirts of Fazilka held by 3/11 Gorkha Rifles, a newly inducted unit. Piara Singh did his best to restore the situation but the destruction of the bridges over the distributary left little chance for manoeuvre. Two of the posts were recaptured on the night of 11/12 December but another counter-attack against Beriwala, put in two nights later, failed. Despite Piara Singh’s efforts the overall situation remained unchanged till the cease-fire. The brigade’s casualties during the 14 days of fighting were 811: 190 killed, 425 wounded and 196 missing.11

The rest of ‘F’ Sector did not see any noteworthy action, except for 51 Independent Parachute Brigade, led by Brigadier E.A. Thyagaraj. This formation was holding an 80 kilometre stretch of the border in the Ganganagar area. Except for three raids across the border to capture prisoners for identification, the area basically remained quiet. It was after the cease-fire that the Pakistanis provoked the paratroopers.

At Jalwala, 1,500 metres from the border. Pakistan’s Eastern Sadiqia Canal forks into three branches. The enemy had a defensive position and a squadron of armour to protect the headworks. India had a BSF post facing the headworks, about a kilometre from the boundary. On 25 December, it was discovered that the Pakistanis had crossed the border and established themselves on a couple of sand-dunes facing the BSF.

A reconnaissance ascertained that regular Pakistani troops had entrenched themselves on the encroachment with anti-tank and anti-personnel mines. As a consequence, Thyagaraj ordered 4 Para to push them out of Indian territory. A company-attack was put in in the early hours of 28 December and the mission was accomplished after a battle that lasted two hours. Though the enemy had only a platoon of its 36 Frontier Force and some Rangers on the encroachment, its artillery played havoc with the assault company and two other companies that had moved forward. It is estimated that the Pakistanis employed 72 artillery pieces in this action. Indian casualties, including those suffered by 9 (Para) Field Regiment, totalled 81: 21 killed (including three officers) and 60 wounded (including two officers). Three of the enemy were captured. However, enemy casualties could not be ascertained as the Pakistanis removed their dead and wounded when they withdrew.

The Barmer sector was under 11 Infantry Division under Major General R.D.R. Anand. The Division had its Headquarters at Ranasar, about 11 kilometres short of the border at Gadra Road.

Some of the fiercest battles of this war were fought by the troops of Western Command. Both sides suffered heavy casualties, Indian casualties totalling 6,524. Of these, 1,628 were killed, 4,131 wounded and 253 missing while 512 were prisoners of war. Pakistan did not announce its casualties. These would, in all probability, have been as heavy.

Once again, formation and higher level command in 11 Corps zone had failed. At Fazilka, the corps commander issued preliminary orders for a portion of ‘F’ Sector to fall back on the Gang Canal, well to the East of the defensive line. This order had to be countermanded by GOC-in-C Western Command. The arrival of Headquarters 2 Corps in the West with 9 Division and 50 (Para) Brigade did provide relief in some measure but it was too late to undo the adverse situations created by 11 Corps’ command structure.

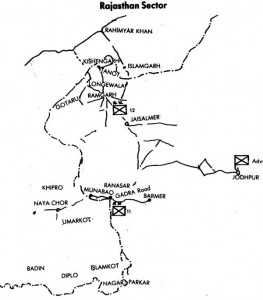

Rajasthan

For operational purposes, the border under Southern Command was divided into four sectors. From North to South, these were Bikaner, Jaisalmer, Barmer and Kutch. The 1971 campaign was, however, largely confined to the Jaisalmer and Barmer sectors due to the poor surface communications in the other two. The Jaisalmer sector was under 12 Infantry Division, commanded by Major General Khambata. The Divisional Headquarters was at Tanot, about 120 kilometres North of Jaisalmer. The Barmer sector was under 11 Infantry Division under Major General R.D.R. Anand. The Division had its Headquarters at Ranasar, about 11 kilometres short of the border at Gadra Road. The divisional centre lines were about 240 kilometres apart in these two sectors. There was no corps Headquarters controlling the forces here. Command was to be assumed by an advanced Headquarters of Southern Command.

| Editor’s Pick |

North of Tanot and parallel to the border, ran Pakistan’s main railway and road system connecting Karachi, her only seaport in West Pakistan, with Lahore. Rahimyar Khan, about 65 kilometres from the border, was an important station, of this railway. The Indian plan was to cut off Karachi from Lahore by capturing Rahimyar Khan with 12 Division. At the same time, 11 Division was to advance to the Naya Chor—Umarkot area and pose a threat to Hyderabad (Sind) (see Fig. 14.5). Before partition, the metre-gauge railway connecting Barmer to Gadra Road and Munabao used to run right up to Hyderabad. Partition had given Gadra Road and Munabao to India but Gadra City went to Pakistan, as also the railway beyond Munabao. The Pakistani authorities had removed a portion of the track near the border and ran their train services only up to Khokhropar, a village about six kilometres form Munabao. Southern Command planned to revive the rail-link between Munabao and Khokhropar and use the line for operational purposes.

Lieutenant General G.G. Bewoor, GOC-in-C, set up his Advanced Headquarters at Jodhpur and divided between the two divisions the combat manpower and equipment at his disposal. The reserves with him comprised one infantry battalion and a squadron of anti-tank guided missiles.12 These could hardly be expected to influence an advance on two widely separated axes.

This was the first time that the Indian Army was to undertake fairly large-scale operations in the desert. From the course of events it would appear that the planners of the campaign did not pay adequate attention to the problems of movement and maintenance in the terrain in which the troops were to operate. They were apparently guided by the experience of campaigns in the Western Desert of North Africa, where many Indian divisions fought the Axis armies during the Second World War. The Thar and Kutch Deserts are, however, quite different from the African one.

The latter allows free movement of wheeled traffic over most of the coastal region and Allied armies could move cross-country on wide fronts. The soft sand of the Thar Desert does not generally permit the movement of wheeled traffic off the road. Though sand tyres were issued to combat formations these soon wore off and replacements were not forthcoming. Provision had been made for laying duckboard tracks but the material available to the two divisions was insufficient for their tasks. Water was another big problem.Plastic containers and Braithwaite tanks were given to units but the carriage of water to forward areas became difficult due to the shortage of bowsers. Besides the inadequacy of engineer resources, a big handicap for Indian commanders was the lack of accurate intelligence regarding the state of communications across the border.

The latter allows free movement of wheeled traffic over most of the coastal region and Allied armies could move cross-country on wide fronts. The soft sand of the Thar Desert does not generally permit the movement of wheeled traffic off the road. Though sand tyres were issued to combat formations these soon wore off and replacements were not forthcoming. Provision had been made for laying duckboard tracks but the material available to the two divisions was insufficient for their tasks. Water was another big problem.Plastic containers and Braithwaite tanks were given to units but the carriage of water to forward areas became difficult due to the shortage of bowsers. Besides the inadequacy of engineer resources, a big handicap for Indian commanders was the lack of accurate intelligence regarding the state of communications across the border.

Click to buy: Indian Army After Independence

Khambata had under him three Infantry brigades, his divisional artillery brigade, 20 Lancers (AMX-13), 3 Independent Armoured Squadron (T -55), and an engineer regiment. At the outbreak of hostilities, one of the infantry brigades held the firm base in the general area Kishengarh-Tanot-Sadhewal-Longewala. The assault brigade was concentrated near Mokal and the follow-up brigade was held in the Sanu area.

Khambata had under him three Infantry brigades, his divisional artillery brigade, 20 Lancers (AMX-13), 3 Independent Armoured Squadron (T -55), and an engineer regiment. At the outbreak of hostilities, one of the infantry brigades held the firm base in the general area Kishengarh-Tanot-Sadhewal-Longewala. The assault brigade was concentrated near Mokal and the follow-up brigade was held in the Sanu area.

Pakistan’s 51 Infantry Brigade, from their 18 Infantry Division, was deployed in the Rahimyar Khan area while their border posts were held by paramilitary personnel. According to Indian intelligence, an armoured regiment equipped with Shermans was in support of this brigade but the enemy was actually able to launch a composite regiment comprising two squadrons of T-59 and one of Shermans (22 Cavalry). Rahimyar Khan itself lay in a canal-irrigated region but to its South, right up to the border, was sandy desert. Pakistan had developed no roads beyond the canal area and the sand belt served as a deterrent to attack.

Southern Command’s offensive was scheduled to start on the night of 4 December. However, due to the lack of preparation in the Jaisalmer sector, 12 Division’s mission was postponed for 24 hours, though preliminary moves had begun earlier. The postponement, in fact, saved Khambata from a good deal of embarrassment.

During the night of 4 December forward elements of 12 Division captured a border post on its route of advance. Operations were also in progress for the capture of Islamgarh, another post on the same axis. Air reconnaissance had earlier been carried out on the evening of 4 December and no enemy activity was noticed on the Islamgarh-Rahimyar Khan route. The reconnaissance did not, however, cover the Gabbar-Longewala axis. Apparently, Khambata expected no enemy initiative from that direction.

Southern Commands offensive was scheduled to start on the night of 4 December. However, due to the lack of preparation in the Jaisalmer sector, 12 Divisions mission was postponed for 24 hours, though preliminary moves had begun earlier.

Islamgarh was captured around 0400 hours on 5 December. Two hours earlier, a patrol from the Indian locality at Longewala, manned by a company from 23 Punjab, had reported the approach of an enemy armoured column. 16 kilometres inside Indian territory, this isolated locality had no anti-tank weapons or mines. The battalion commander rushed two recoilless guns to the locality and informed the brigade and divisional commanders of the developments.

Khambata alerted the air-base at Jaisalmer and asked for a strike at first light. Meanwhile, it fell to Major Kuldip Singh Chandpuri, the company commander at Longewala, to hold out till the arrival of air-support and reinforcements. It was a moonlit night and his men could soon see the Pakistani T-59s and the infantry that accompanied them on jeeps take up positions on a ridge about 300 metres away. His machine-gunners and the crews of the newly received recoilless guns engaged at very high rates of fire. From its volume, the Pakistanis assumed that Longewala was strongly held and decided to encircle the locality instead of storming it. They kept engaging it with fire. It is possible that a strand of barbed wire that ran around the locality to keep stray dogs out gave them the impression that it was a protective minefield marker.

The air-strike came promptly at first light. Jaisalmer had only two Hunters in serviceable condition but the Air Force put them to good use. Sortie after sortie was flown. The tanks around Longewala and those strung on the track leading to it were sitting ducks. Guided by the air observation pilots in their tiny Krishaks, the Hunters shot them up. The air action continued throughout 5 December. Surprisingly, the Pakistan Air Force did not show up. By midday, 17 tanks and 23 other vehicles had been written off. It later transpired that the enemy had launched this offensive without arranging for air-support or even ground air-defence weapons.

Plans captured from the tanks showed that the Pakistanis had wanted to outflank the Indian troops deployed in the Tanot-Kishengarh area. They expected to have breakfast at Ramgarh and dinner at Jaisalmer. Coming as they did without any air-cover and, as it later turned out, without enough water and food, their venture was extremely foolhardy. But it did mess up General Bewoor’s plans.13 Had the Pakistani thrust come on 6 or 7 December when 12 Division would have been plodding through the desert towards Rahimyar Khan, the consequences would have been much more serious.

Plans captured from the tanks showed that the Pakistanis had wanted to outflank the Indian troops deployed in the Tanot-Kishengarh area.

The Army Commander now had two options. He could contain the enemy on the Longewala axis and go ahead with his offensive, with the knowledge that the enemy had already committed most of its armour and would not be able to divert it to Rahimyar Khan in time to interfere with the Indian advance. Alternatively, he could direct his assault force on Longewala. But he did neither, and ordered the entire division to adopt a defensive posture.14 To reinforce it, he sent a troop of anti-tank guided missiles out of his reserve.

On 6 December, enemy artillery kept shelling Longewala intermittently. A second Pakistani column was sighted South of Kharotar that day. An air mission sent to strafe it reported that the column had bogged in the sand on the Gabbar-Longewala axis. This was the second prong of the Pakistani offensive but it had lost direction in the desert and converged on its first column.

Manekshaw was riled when he saw that no advantage was being taken of the enemy’s discomfiture. On his urging, Bewoor ordered 12 Infantry Division to go on the offensive and “destroy the enemy force quickly and, if possible, by last light on 8 December”. 15 Bewoor, however, stipulated that the divisional plan should be based on brigade attacks and that Khambata should submit it for his approval by 1100 hours the next day (7 December).

This dithering angered Manekshaw. There was no question of set-piece attacks as visualized by the Army Commander; all that was required was bold pursuit before the enemy recovered its breath and got away. As a last resort, Manekshaw, sent a personal message to Khambata on 7 December to get on with the job.

| Editor’s Pick |

In spite of this, the pursuit began after the enemy’s withdrawal was well under way. The Pakistanis were quick to act. They replaced the commander of their 18 Division, responsible for mounting the offensive. The new commander seized the initiative and promptly ordered a withdrawal. According to Pakistani accounts, there was no pursuit of their forces.

Khambata’s advance was slow. There was, however, some rear-guard action near the border and thereafter about 640 square kilometres of empty desert was captured. According to Indian estimates, Pakistan lost 24 tanks, five field guns, four air-defence guns and 138 vehicles in the offensive.

After the Longewala episode, Bewoor asked for a change in his task as he felt that the resources with him were inadequate for the capture of Rahimyar Khan. Manekshaw was at first adamant, but the slow pace of the ‘pursuit’ made him change his mind. Bewoor’s recommendation was to leave one brigade of 12 Infantry Division in the Jaisalmer area, send one to reinforce 11 Division and another to the Kutch sector. Manekshaw accepted the transfer of only one brigade as he did not want to jeopardize the security of Northern Rajasthan, where he foresaw a threat from Pakistani reserves held around Multan.

Opposite 11 Division, too, the enemy had just one brigade group with paramilitary personnel holding border outposts. Major General Anand deployed one infantry brigade group in his firm base in the Gadra Road-Munabao area, while the rest of his division was held in the rear. In the shape of armour he had one independent squadron. To assist him, 10 (Para) Commando (less a group)16 was to operate in a ground role against enemy lines of communication. This unit was, however, directly under Southern Command for operational purposes. The success of the division depended largely on the speed with which the rail-track between Munabao and Khokhropar could be made operational.

The divisional plan envisaged the capture of Khokhropar and Gadra City on D plus one day. A firm base was thereafter to be established by the leading brigade for a divisional attack on Naya Chor, the main enemy position before Umarkot. The leading brigade was to complete this task by D plus two days, and Naya Chor was expected to fall in the next six days. The main axis of advance was to be Munabao-Khokropar-Parbat Ali, while a subsidiary thrust was to make for Khinsar and Chachro.

The advance began on the evening of 4 December. The enemy Air Force was very active but despite its efforts the division took its initial objectives by 5 December. The leading brigade took Khokhropar against light opposition and the brigade holding the firm base took Gadra City and Khinsar. At the same time a camel battalion (17 Grenadiers), deployed North of the main divisional axis, made good progress. By 7 December it had taken several enemy posts opposite the Myajlar-Sundra area and was thereafter ordered to consolidate its gains and guard this axis against infiltration.

The advance began on the evening of 4 December. The enemy Air Force was very active but despite its efforts the division took its initial objectives by 5 December. The leading brigade took Khokhropar against light opposition and the brigade holding the firm base took Gadra City and Khinsar. At the same time a camel battalion (17 Grenadiers), deployed North of the main divisional axis, made good progress. By 7 December it had taken several enemy posts opposite the Myajlar-Sundra area and was thereafter ordered to consolidate its gains and guard this axis against infiltration.

Anand’s difficulties surfaced soon after the initial successes. The road beyond Khokhropar was found to be a desert track. Indian intelligence had reported it earlier as a tarmac highway. This meant the laying of a duckboards. The division’s engineer resources were woefully inadequate for this task. The requirement of duckboard, originally estimated for a 10-kilometre stretch, now shot up to 60 kilometres. Laying the duckboard track required much effort due to the sand-dunes that ran across the track and were as high as 50 metres at some places. To augment the division’s engineer capability,17 a Railway Engineer Group (TA) and an Army Engineer Regiment were rushed in. At the same time, a Road Maintenance Unit and two Pioneer Companies were sent to the divisional area.

By 7 December the leading brigade had taken Parche-ji- Veri, on the route to Naya Chor and on the Southern axis, Dali and Mahendro-or-par were also taken. That day the Engineers were able to run the first train to Khokhropar but it was strafed from the air soon after its arrival.

The first major engagement in this sector took place in the early hours of 13 December, when the leading brigade put in a silent attack and captured Parbat Ali after a stiff battle.

The para commandos crossed into Pakistan after dusk on 5 December. The task given to them was to raid Umarkot, a canal-bridge in its vicinity, Chachro, Virawah and Nagar Parkar. However, for some reason, Southern Command cancelled the operations in the Umarkot area and the group heading in that direction was recalled. The raid on Chachro took place in the early hours of 7 December. The commandos cleared the town, capturing nearly 20 prisoners and a good quantity of arms and ammunition. On the following night they operated against Virawah and later against Nagar Parkar, after which they returned to their base. Hardly any advantage, however, was taken of their good work. The formation advancing from the direction of Dali-Khinsar had been ordered to occupy Chachro after the raid. But its troops arrived a day later. The enemy had by then returned, with the result that the town had to be fought over again.

By the evening of 8 December, the leading brigade had arrived in front of a high feature called Parbat Ali. The enemy had a screen position here, behind which lay the main Naya Chor defences. The latter were held by about two battalions of infantry, with armour in support. That day the Pakistanis attacked the leading Indian elements, but were thrown back. The follow-up brigade had, by this time, fetched up in the Parche-ji-Veri area, though the duckboard track was still far behind and the forward troops were without water.

By 11 December the follow-up brigade was also leaning on Parbat Ali. An attempt by Anand’s solitary squadron of armour to outflank this position failed. To give more punch to 11 Division, a brigade group from 12 Division, together with two squadrons of armour, was now ordered to this sector. However, in a situation where the troops already with 11 Division could not be maintained, the additional brigade would only add to the administrative difficulties.

The first major engagement in this sector took place in the early hours of 13 December, when the leading brigade put in a silent attack and captured Parbat Ali after a stiff battle. The enemy left behind 57 dead and 35 prisoners. It later put in three counter-attacks to retake the position, failing each time.

| Editor’s Pick |

Meanwhile, efforts continued to push forward the duckboard road and to build up for the attack on Naya Chor. On 15 December, a probing mission against its defences was severely mauled. In fact, the Pakistanis had by this time reinforced this sector with a brigade group, which included a regiment of armour, from their 33 Infantry Division. Anand’s chances of taking Naya Chor had thus receded sharply. On13 December, he had sent a battalion group from Chachro to develop a threat towards Umarkot from the South-East. The group made good progress and reached Hingrotar on 16 December. However, the next day, before the field guns supporting the battalion could catch up with it, the enemy attacked, forcing it to fall back to Chachro.

The cease-fire came while 11 Division was still building up for its projected attack on Naya Chor. The BSF had done well in the Bikaner and Kutch sector, capturing about 50 enemy border outposts ‘which had either been vacated by the Rangers or Mujahids, or where opposition was light’.18 At one stage, around 8 December, Army Headquarters had suggested to General Bewoor that one brigade group of 12 Division be sent to Kutch to operate towards Badin, South of Hyderabad, but administrative problems precluded a quick switch-over. Bewoor, however, ordered the para commandos to raid Badin on 12 December. Later, when it was discovered that there was no suitable route for infiltration towards Badin, he ordered raids on Islamkot and Diplo.

It was for the first time in the history of Indo-Pak conflicts that a decision to end hostilities was not dictated by the UN or an external mediator. President Yahya Khan kept his people in suspense for several hours after the Indian announcement.

Making a 64-kilometre advance from Nagar Parkar during the night of 16/17 December a commando group raided Islamkot at dawn but found that the enemy had left the town a week earlier. Later, on the way to Diplo, the group shot up an enemy motor detachment. By the time the commandos could dispose of the captured material and send back the prisoners, it was too late to go for Diplo before the cease-fire, and they exfiltiated to their base.

The Rajasthan campaign ended before Southern Command could reach the green belt in Sind. The extent of territory it captured was quite large – 12,200 square kilometres – but it was all a sandy waste.19 Better results might have accrued had some of the basic principles of warfare not been disregarded. Instead of concentrating the available resources on a worthwhile axis at a time, an advance on two divergent axes was undertaken simultaneously. Planning lacked imagination as was shown by the last-minute scramble for engineer stores and personnel. There could be no better proof of the low state of Indian intelligence than its failure to discover the condition of surface communications in territory that was only a few kilometres from the border. On the other hand, 12 Division took no notice of the information given by the civil authorities regarding Pakistan’s preparations opposite Longewala and Sadhewala.

CEASE-FIRE

On 16 December, after the surrender of his Army in East Pakistan, President Yahya Khan made a broadcast to his people that it was merely the loss of a battle and that the war would go on. The Indian Government, however, had no intention of prolonging the conflict as that would mean further loss of life and property and suffering for countless people. Accordingly, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi announced in the Parliament on 17 December that Indian armed forces had been given instructions to cease operations from 2000 hours that day on all fronts in the West.

It was for the first time in the history of Indo-Pak conflicts that a decision to end hostilities was not dictated by the UN or an external mediator. President Yahya Khan kept his people in suspense for several hours after the Indian announcement. However, the realities of the situation must have dawned upon him soon enough, for he accepted the cease-fire before the deadline fixed by India. It is unlikely,that he was not aware about the reinforcement of the Western theatre by India, with troops withdrawn from the East. A part of 11 Corps had begun moving to Punjab, and the first troops had arrived there on 13 December.

It was for the first time in the history of Indo-Pak conflicts that a decision to end hostilities was not dictated by the UN or an external mediator. President Yahya Khan kept his people in suspense for several hours after the Indian announcement. However, the realities of the situation must have dawned upon him soon enough, for he accepted the cease-fire before the deadline fixed by India. It is unlikely,that he was not aware about the reinforcement of the Western theatre by India, with troops withdrawn from the East. A part of 11 Corps had begun moving to Punjab, and the first troops had arrived there on 13 December.

Some people later asserted that India wanted to destroy West Pakistan after finishing the campaign in the East and that the cease-fire was announced under-pressure from a particular country or countries. The author asked Field Marshal Manekshaw whether there was any truth in this assertion. “There was no pressure on me or the Prime Minister,” he said. “And I can’t believe that any country can put pressure on Indira Gandhi”.

NOTES

- Northern Command was created later and made responsible for the Jammu & Kashmir region.

- Its one infantry brigade was with their 23 Infantry Division.

- Defence of the Western Border, by Major General Sukhwant Singh, p. 12.

- According to one source, the guns of the two forward batteries of this regiment were damaged when the depth battery engaged the enemy in the direct lay.

- Now Jammu & Kashmir Light Infantry.

- This battalion was under 15 Corps.

- The regiment is also known as the Poona Horse.

- Defence of the Western Border, by Major General Sukhwant Singh, p. 41.

- Ibid., p. 143.

- lbid., p.138.

- Ibid., p.159.

- Ibid., p. 192.

- Major General Sukhwant Singh was Deputy Director of Military Operations at Army Headquarters at the time. In his book Defence of the Western Border (pp. 237-8), he says that when he visited Longewala after the cease-fire, he was told by the Collector of Jaisalmer that he had informed 12 Division on 30 November 1971, of the evacuation of villages on the Pakistan side of the border and had also reported that the Pakistanis were improving the tracks in their territory leading to Longewala and Sadhewala. Obviously no notice was taken of this information.

- Ibid., pp. 212-3.

- Ibid., p. 214.

- One group of this battalion was assigned to 12 Infantry Division to operate in an airborne role in the Rahimyar Khan area. After the cancellation of that mission, this group remained unutilized till the cease-fire.

- The division originally had only its integral Engineer regiment and an independent field company.

- Defence of the Western Border, by Major General Sukhwant Singh, pp. 230-1.

- Ibid., p. 231

Surprising to see that the role of 2nd Bn BSF is completely ignored in the narration. This battalion had established bridgehead across the salt flats of Suigam sector and had attacked and overrun the towns of Virawah and Nagar Parkar. Assistant Commandant T. P. Singh was awarded Sena Medal and the commandant, Lt Col L B Kane was awarded VSM for these crucial battles, establish firmbase from which 10 Para conducted further ops.