The Indian cabinet met on 28 April 1971. General Manekshaw was told to attend the meeting as he was Chairman of the Chiefs of Staff Committee. Without much ado, he was told to take charge of the situation. When he asked what was actually required, he was told: “Go into East Pakistan”. He pointed out that this would mean war. ‘We don’t mind it,’ was the reply.1

Till the middle of April the Army had not even been told of the BSF backed Mukti Bahini operations. Manekshaw now explained that war was not something one started casually. No plans had yet been made and a good deal of preparation was necessary. Even the time was not opportune. A war with Pakistan now would mean fighting on two fronts – in Bengal and in Punjab and possibly on a third front, if the Chinese decided to intervene. This was harvest-time in Punjab and if the troops moved forward at this juncture, it would not be possible to reap the harvest. This would mean famine in the land. Also, the Himalayan passes would soon open and the Chinese might give an ultimatum, as they did in 1965. That would make it impossible for him to pull out any troops facing the Chinese for operations in East Pakistan.

Manekshaw also pointed out that the monsoon broke in the Eastern region in the middle of May; thereafter, till late autumn, Bangladesh would be one big marsh. Confined to the roads, the Indian Army could be stopped easily. There were three divisions in West Bengal at the time. They had been split into penny packets to maintain peace in the state and were without their heavy weapons. To collect these divisions and to train them for operations would take some months. His most telling argument was in respect of India’s only armoured division. Most of its armour was unfit for operations due to the lack of spare parts, for which the Finance Ministry had till then refused funds. He finally said: “I guarantee you hundred per cent defeat if you want to go in now”.

The target set by Manekshaw was to train and equip three brigade groups of regular Bangladesh troops, organized to function independently.

Mrs Gandhi dismissed the meeting but asked Manekshaw to stay back. Left alone with her, he straightaway offered to resign on some pretext if that suited her. But it was not his resignation that the Prime Minister wanted. What she did not like was the Chief’s blunt manner. “Well, it is my job as your Army Chief to put the facts before you,” Manekshaw told her. Then he added: “If your father had had me as his Chief and not General Thapar he wouldn’t have been shamed in 1962”.

The upshot of the meeting was that planning and preparation began for a possible operation in East Pakistan in case further diplomatic efforts failed to solve the refugee problem. The task of training and guiding the Mukti Bahini was also taken over by the Army, though the latter was not to enter East Pakistan. The target set by Manekshaw was to train and equip three brigade groups of regular Bangladesh troops, organized to function independently. Their main content would be the personnel of the East Bengal Regiment, the shortfall being made up by men from the East Pakistan Rifles. At the same time, about 70,000-80,000 guerrillas were to be trained and equipped. Their training, which till then had been sketchy, was to be improved. Recruits for the guerrilla force were to be found from among the young able-bodied refugees as also the ranks of the East Pakistan Rifles.

Manekshaw wanted a quick, decisive campaign that would be over before any outside intervention could materialize. Towards this end, he planned multi-pronged thrusts from the East, North and West; the Navy would blockade the province’s ports and the Air Force would destroy or ground the enemy Air Force. It was foreseen that Pakistan would attack in Punjab; and possibly in Kashmir also, in case India launched large-scale operations against East Pakistan. However, offence being the best form of defence, it was decided that in that theatre also a posture of offensivedefence would be maintained; a limited campaign formed part of it.

Auroras commitment was the defence of the borders and counter-insurgency operations in Nagaland and Mizoram.

Lieutenant General Jagjit Singh Aurora was the GOC-in-Chief Eastern Command at this time. As such, the task of detailed planning and preparation for operations in East Pakistan, as also the Mukti Bahini commitment, fell to him. A quiet but confident Commander, Aurora had taken over Eastern Command in June 1969 from Manekshaw. He belonged to the 2nd Punjab Group and had commanded its 1st Parachute Battalion with distinction in the Jammu & Kashmir operations of 1948, where he also commanded 19 Infantry Brigade during the Punch link-up. A cautious and careful man, he believed in facing a given situation after due thought and preparation. Once the ball was set rolling, he led the team with vigour.

Eastern Command, with Headquarters at Fort William (Calcutta), was responsible for the whole of North-East India. It had two corps under it: 4 Corps and 33 Corps (for total force levels on both sides, see Appendix 2). Aurora’s commitment was the defence of the borders and counter-insurgency operations in Nagaland and Mizoram. His troops were, however, equipped and trained for warfare in mountainous areas, except for the division responsible for the defence of West Bengal. Thus, except for this division, his formations had very little armour and their artillery consised mostly of towed mountain guns, which were too light to be effective against well-prepared defences. Moreover, the troops on counter-insurgency role had no artillery at all. Also, large quantities of bridging and river-crossing equipment would be needed for the operations in East Pakistan.

Aurora saw that his biggest difficulty would be in regard to the bases for launching the operations, particularly in the Tripura and Meghalaya regions, which had hardly any roads at the time. The airfields in the area would also need improvement. The work of building the essential roads, and the improvement of airfields was taken in hand straightaway; it continued through the rainy season. Aurora estimated that he would need eight divisions for the task. However, while allocating troops and equipment to Eastern Command, Manekshaw had to strike a balance between the requirements of the two theatres. He gave Aurora the bridging and river-crossing equipment, the artillery and the armour that he needed. In infantry, Aurora got his eight divisions but in equivalents: a number of ad hoc brigade-sized forces were raised and given over to him.

A serious snag in the scheme was the likelihood of intervention by China. Some degree of insurance against this eventuality was achieved when, on 9 August, India signed a treaty of friendship and co-operation with the USSR. The treaty catered for mutual consultations in case of aggression or a threat of it. All the same, Aurora had to be very careful in the use of formations normally committed to the defence of the Northern borders. It was after a good deal of changing and chopping that he was able to muster the requisite forces. For the effective control of operations he was given a third Corps Headquarters. This was done by raising Headquarters 2 Corps early in October.

…on 9 August, India signed a treaty of friendship and co-operation with the USSR. The treaty catered for mutual consultations in case of aggression or a threat of it.

The Bangladesh assignment would commit the Indian Army for the first time since Independence to large-scale operations on two fronts which were 1,600 kilometres apart. It would be an all-out war. As Chairman of the Chiefs of Staff Committee, the task of co-ordinating the aspects that concerned all three Services fell to Manekshaw. With his knack for evoking a team spirit among those who worked with him, he got the unstinted co-operation of the other Chiefs: Admiral S.M. Nanda and Air Chief Marshal P.C. Lal.

Besides inter-service co-ordination, Manekshaw had the gigantic job of co-ordinating the planning and preparation within the Army, as also with the civil authorities concerned. The personal prestige that he had built up over the years and his rapport with the Prime Minister helped him immensely in orchestrating various organs of the Government towards the common national goal. Manekshaw worked in close concert with D.P. Dhar, Chairman of the Policy Planning Committee of the Ministry of External Affairs. This enabled him to cut through the red tape. Reminiscing about this period, Manekshaw said:

“I got everything I wanted. I got the money. I went to the Soviet Union and got Soviet tanks; went elsewhere, got the equipment I wanted much against the wishes of the bureaucracy; they don’t like such things coming into the hands of the Service Chief, especially a Service Chief who took no notice of them. It was all done against their opposition but I had the Prime Minister’s support. She knew what the aim was and she understood that this man would carry it out”.2

I must make a mention here of the tremendous spade-work done by the staff at Army Headquarters and lower formations to get ready for the eventuality of war. A scheme for the reorganization and re-equipment of the Army, specially affecting the Armoured Corps and Artillery, was under way at this time. Many units were under-strength, besides being deficient in equipment. The reorganization and re-equipment was completed in record time and a crash programme taken in hand at regimental and corps centres to turn out combat soldiers by cutting down the training period.The lessons of 1965 were not ignored. The annual turnover programme of units was held in abeyance. Reservists were called up for training before the monsoon and were kept on till after the war. Leave was restricted to keep units at a reasonable level in preparedness. Deficiencies in the officer cadre were made up by pruning the staff at Army Headquarters and other static Formation Headquarters. Courses of instruction for officers were cancelled and a scheme was drawn up to utilize the instructional staff at officer training establishments and the students at the National Defence College. Territorial Army units were embodied and made effective well before the commencement of hostilities. Several measures were effected to improve the jawans’ morale. These included better financial assistance to the dependents of battle casualties.

While these preparations were under way, the Indian Government did all that was possible to solve the refugee problem by peaceful means. It gave wide publicity abroad, through diplomatic missions and special delegations, to the colossal problem that the refugees posed for the country. These efforts brought much sympathy but no practical help for sending them back to their homes. As a last resort, Mrs Indira Gandhi undertook two tours abroad to personally brief the heads of government of important countries. She went to the Soviet Union towards the end of September. Her visit to countries of the Western bloc – Belgium, Austria, the United States, the United Kingdom, France and West Germany – was undertaken from 23 October to 13 November. However, the effort brought no tangible results.

Besides the Mukti Bahini, there were several independent guerrilla groups within East Pakistan. Prominent among these were the Qadir Bahini and the Mujib Bahini.

The United States could have played a crucial role in defusing the situation in the sub-continent. It could have used its immense influence to persuade Yahya Khan to check himself and restart a political reconciliation process. It could be done as Pakistani commentators themselves maintain.

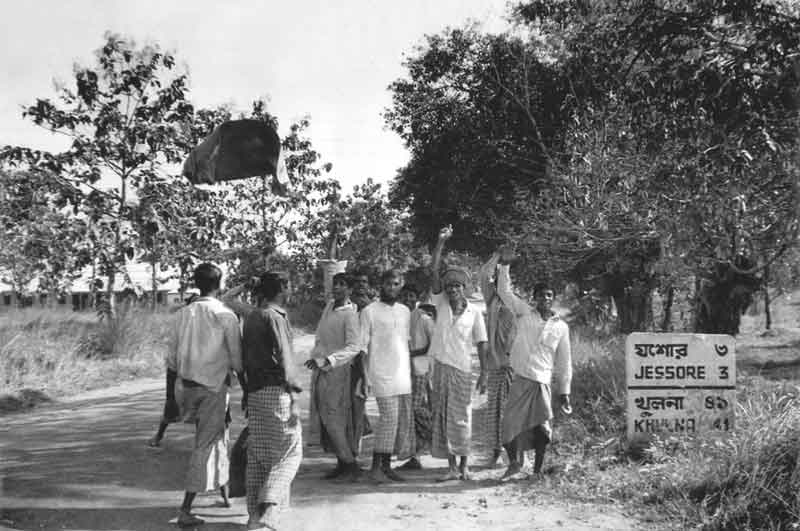

Over the months the Mukti Bahini had been gaining in strength. From August onwards its operations showed more daring and better leadership. In October, it began to liberate small chunks of territory in the border areas, Pakistani authorities claimed that such operations had the backing of Indian troops and artillery. Besides the Mukti Bahini, there were several independent guerrilla groups within East Pakistan. Prominent among these were the Qadir Bahini and the Mujib Bahini. The former operated in the Tangail area and attained a strength of 16,000-20,000. The Mujib Bahini, which was equally large, operated around Dacca.

Confronted by insurgents from across the border and from within, the Pakistan Army came under greater stress. With a strength of about 42,000 regular troops, it had to contend with rebellion spread over the whole of East Pakistan. Though it was able to maintain its hold over most of the province, the prolonged counterinsurgency operations left their mark. Casualties were heavy: 237 officers, 136 JCOs and 3,559 other ranks.3

The stepping up of the Mukti Bahini’s operations forced Lieutenant General A.A.K. Niazi, GOC-in-C Pakistani Eastern Command, to move a large number of his regular troops to defend the border areas, which had normally been the responsibility of paramilitary personnel. A veteran of the Second World War, during which he had won the Military Cross, Niazi was tall, well-built, and full of self-confidence. He had the reputation of being a soldier’s general and the Indo-Pak conflict of 1965 had brought him the Hilal-i-Jurat, Pakistan’s second highest award for gallantry. Flamboyant in his lifestyle, he was said to be fond of the good things of life. According to Lieutenant Colonel Salik, his Public Relations Offlcer, Niazi was given to bluff and boasting. “He declared several times that if war broke out, he would take the battle to Indian territory. In his loud fantasies, his attack sallied at one time, towards Calcutta and, at another, towards Assam”.4

Reacting to Pakistani moves and pronouncements, the Indian Army took precautionary steps. The formations on internal security duties in West Bengal and Bihar had, by the end of August, collected their heavy weapons and begun to move to their concentration areas. About the same time, other formations allotted for the task in East Pakistan also began to assemble.

Bangladesh is not ideal campaigning ground. Though most of it is flat country, except for the hilly tracts of Chittagong and Sylhet, nearly a quarter of its area is covered by lakes, rivers and swamps. Three great rivers, with their numerous tributaries and distributaries, meander across its vast plains: the Ganga (called the Padma locally), the Brahmaputra (known locally as the Jamuna), and the Meghna. Before reaching the Bay of Bengal they form vast deltas, the creeks running far inland. Ample monsoon rains and alluvial soil produce a luxuriant growth of vegetation, vast fields of paddy and other crops. Though one of the most densely populated regions of the world, then with a population of about 75,000,000 in an area of 143,272 square kilometres, its surface communications are poor. Inland water-transport is the mainstay, The rail system is sketchy; the numerous ferries that link segments of railways and roads, are a peculiar feature of the region. The major rivers then had no bridges, except for two: Hardinge Bridge over the Ganga and the Ashuganj Bridge over the Meghna.

Its rivers divided the province into four main sectors. The Eastern Command decided to allot the responsibility for operations in relation to the riverine divisions. The tract nearest Calcutta came to be known as the South-Western Sector. It comprised the area lying South and West of the Ganga. Placed under 2 Corps (Lieutenant General T.N. Raina, MVC), the sector had its Headquarters at Krishnanagar (see Fig.). It had under command 4 Mountain Division, 9 Infantry Division and a regiment plus of armour, besides the divisional and corps complement of artillery.

Its rivers divided the province into four main sectors. The Eastern Command decided to allot the responsibility for operations in relation to the riverine divisions. The tract nearest Calcutta came to be known as the South-Western Sector. It comprised the area lying South and West of the Ganga. Placed under 2 Corps (Lieutenant General T.N. Raina, MVC), the sector had its Headquarters at Krishnanagar (see Fig.). It had under command 4 Mountain Division, 9 Infantry Division and a regiment plus of armour, besides the divisional and corps complement of artillery.