The South China Sea Imbroglio

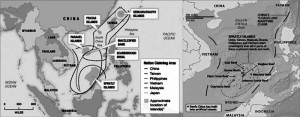

At the heart of the South China Sea dispute is the “Nine-Dash Line”, Beijing’s claim that encircles as much as 90 per cent of the contested waters. The line runs as far as 2,000 km from the Chinese mainland to within a few hundred kilometres of the Philippines, Malaysia and Vietnam. Beijing maintains it owns any land or features contained within the line, which confers vaguely defined “historical maritime rights”.

The Chinese bided their time, integrated into the world market and became one of the largest trading partners with the ASEAN…

The discourse on the South China Sea disputes is understandably laden with emotion. It appeared on a Chinese map as an 11-Dash Line in 1947 as the then Republic of China’s Navy took control of some islands in the South China Sea that had been occupied by Japan during the Second World War. After the People’s Republic of China was founded in 1949, and Kuomintang forces fled to Taiwan, the communist government declared itself the sole legitimate representative of China and inherited all the nation’s maritime claims in the region.

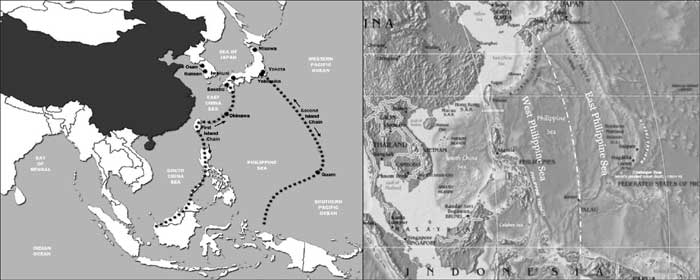

But two “Dashes” were removed in the early 1950s to bypass the Gulf of Tonkin as a gesture to communist comrades in North Vietnam. A look at the choke points along the access routes to the South China Sea, the approaches available to the US naval fleet and the location of its naval fleet, especially the nuclear submarines brings out the issue in stark reality. This is the key for it to achieve its Maritime Strategy as enunciated in 1986 by Admiral Liu Huaquing.

Seen in the backdrop of the approaches available to the US Navy, Hainan Island in the South China Sea, where the PLAN has its nuclear submarine base, is the most critical location. Thus, the importance that China gives to South China Sea, as it struggles to counter ‘The Revenge of Geography’.

As per Admiral Liu Huaquing, PLA Navy needed to develop four capabilities:

As per Admiral Liu Huaquing, PLA Navy needed to develop four capabilities:

- The ability to seize limited sea control in certain areas for a certain period of time

- The ability to effectively defend China’s sea lanes

- The ability to fight outside of China’s claimed maritime areas

- The ability to implement a credible nuclear deterrent.

Bernard D Cole, in his article “The Great Wall at Sea: China’s Navy in the Twenty-First Century”, 2nd edition, (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2010) notes, “…the PLA Navy’s capability to fulfill the requirements of its ‘Offshore Defense’ strategy were to develop along three phases:

On July 12, 2016, a United Nations tribunal ruled that China’s sovereignty claims over the South China Sea and its aggressive attempts to enforce them violate international law…

Phase 1: To be achieved by 2000, during which time the PLA Navy needed to be able to exert control over the maritime territory within the First Island China, namely the Yellow Sea, East China Sea and South China Sea — a goal that Cole argues China has yet to fully achieve. But the deployment of Chinese weapons on its Eastern Seaboard and its effective reach belies this notion.

Phase 2: To be achieved by 2020, when the Navy’s control was to extend out to the Second Island Chain. It is for this phase that China wants to secure the South China Sea and deploy its aircraft and missiles on the artificial islands created to ensure effective dominance up to the Second Island Chain or at least till the West Philippine Sea. This will enable it to gain unhindered access to the Indian Ocean – the Phase most critical for India as China would then be aggressive against it along both its Northern and Maritime borders, without fear of intervention by the US Navy as it would be fighting well beyond its maritime boundaries with them and be able to defend its sea lanes of communications. It would, thereby, have fulfilled three out of the four capabilities as listed by Admiral Liu Huaquing.

Phase 3: To be achieved by 2050, by which time the PLA Navy is to evolve into a true global navy and launch itself on to the ‘open seas’. By then the development of the SSBN fleet would also have been completed and the PLAN would be in a position to provide effective nuclear deterrence.

Before pushing aggressively in the South China Sea and learning its lessons from the earlier push in the late 1980s and early 1990s, China evolved its ‘Unrestricted Warfare’ by going beyond conventional war and entering into domains that are quasi-military and non-military. While the 1980s had a different geo-strategic impulse, post First Gulf War, China realised that the methods of pure military deterrence were passé and the need was for economic, commercial, diplomatic, socio-political deterrence – their concept of ‘Unrestricted Warfare’ akin to the US concept of ‘Full Spectrum Dominance’.

India needs to realise that South China Sea is but a step towards China’s ultimate goal of being the sole arbiter in Asia and later, the world…

Thus, the Chinese bided their time, integrated into the world market and became one of the largest trading partners with the ASEAN. Concurrently, China developed and deployed its missiles, new generation fighters, ships, nuclear submarines and cruise missiles on its Eastern Seaboard thereby ensuring effective weapons coverage up to the First Island Chain and some coverage beyond.

Having achieved it by 2010-2012, China now began its assertive push into the South China Sea by reclaiming rocks and atolls, and converting it into islands to expand its military presence in the area. To guard its Eastern Seaboard, China needs to control the Senkaku, Pratas, Paracel and Spratly Islands and the Scarborough Shoals (the case referred to PCA by the Philippines), and these are where the Chinese push has come about over the last few years.

The Way Ahead

On July 12, 2016, a United Nations tribunal ruled that China’s sovereignty claims over the South China Sea and its aggressive attempts to enforce them violate international law. The Hague-based Permanent Court of Arbitration found that China’s main claim to the sea, represented by its notorious “Nine-Dash Line” map, has “no legal basis.” It further slammed China’s frequent claims to “historic” rights, confirming that these do not fly under the UN Law of the Sea Treaty and that there is “no evidence that China had historically exercised exclusive control over the waters or their resources.” China has said it will not accept a ruling against it in a key international legal case over strategic reefs and atolls that Beijing claims would give it control over disputed waters of the South China Sea.

The Chinese President, Xi Jinping, said China’s “territorial sovereignty and marine rights” in the seas would not be affected by the ruling, which declared large areas of the sea to be neutral international waters or the Exclusive Economic Zones of other countries. He insisted China was still “committed to resolving disputes” with its neighbours. A clever policy, as individually each country could succumb to the lure of Chinese investment, as is evident from the responses of the Philippines President Rodrigo Duterte, who took office June 30 promising better relations with China. He wants bilateral talks, Chinese investment and joint resource development in the South China Sea.

The Chinese President, Xi Jinping, said China’s “territorial sovereignty and marine rights” in the seas would not be affected by the ruling, which declared large areas of the sea to be neutral international waters or the Exclusive Economic Zones of other countries. He insisted China was still “committed to resolving disputes” with its neighbours. A clever policy, as individually each country could succumb to the lure of Chinese investment, as is evident from the responses of the Philippines President Rodrigo Duterte, who took office June 30 promising better relations with China. He wants bilateral talks, Chinese investment and joint resource development in the South China Sea.

The UN may have to do some soul-searching on whether China should be a part of it and gain from its Institutions, if it is not ready to abide by International Laws…

By stressing that, “India supports freedom of navigation and over-flight and unimpeded commerce based on the principles of international law, as reflected notably in the UNCLOS,” the MEA statement was seen as chiding China. Emphasising India’s specific national interest in the issue, it added, “States should resolve disputes through peaceful means without threat or use of force and exercise self-restraint in the conduct of activities that could complicate or escalate disputes affecting peace and stability.” The demand for “utmost respect,” the assertion of India’s vital interest in maintaining “freedom of navigation and over-flight rights under UNCLOS” and aversion to “activities that complicate or escalate disputes” – all implied strong criticism of Beijing’s intention to reject the tribunal’s verdict and continue as before.

Is that enough? India needs to realise that South China Sea is but a step towards China’s ultimate goal of being the sole arbiter in Asia and later, the world. That status it can achieve only if its Navy can get unrestrained access to the Indian Ocean in the first phase and the Pacific and Atlantic thereafter. Control over the South China Sea is critical towards this step and hence the vitriolic response in the Chinese media against this judgment.

The response has to be a joint concerted push in all domains, military, trans-military and the non-military domains. Plans need to be made by the leading economists on a step-by–step approach to counter the Chinese economic creep and overcome the impact on world economy should China respond vehemently. At the same time, maybe the UN may have to do some soul-searching on whether China should be a part of it and gain from its Institutions, if it is not ready to abide by International Laws and norms to which it is a signatory.

Chinese economic coercion needs to be curbed and the bamboo-curtain that it has erected be opened up in a phased manner…

Is there a case to re-look the various shadow institutions that China has created and put certain rules and curbs in place to deny Chinese economic arm-twisting of the under-developed countries? Should there be such shadow organisations or re-cast and strengthen existing bodies? India needs to ensure a joint calibrated response to this Chinese thrust. Even as it seeks to gain control of the South China Sea and is procrastinating in resolving the land boundary, it is keen to enter the Indian market, financial market et al, while it blocks all attempts by the Indian entrepreneurs’ in entering the Chinese markets. Reciprocity has never been a part of the Chinese push, as these thrusts are all a part of its ‘Unrestricted Warfare’. Hence it has the fear of a blowback in its backyard akin to what it aims to achieve in other countries.

In what manner can the ARF ensure a joint military and trans-military response to China’s aggressive stance of claiming the South China Sea as its exclusive domain? Would the arming of the ASEAN countries with THAAD, cruise missiles, anti-ship missiles and UCAVs prove beneficial in the long run? Should all ASEAN countries also follow an asymmetric response like the Chinese and inhibit the artificial islands and PLAN movement with hundreds of fishing boats and trawlers? However, before such a step, they would need to ensure a quick joint response to any PLAN adventurism against it.

For India, these are crucial times and it should ensure ASEAN solidarity and a joint response to this imbroglio, a united front of South China Sea claimants (the Philippines, Vietnam, Indonesia, Malaysia, Brunei) negotiating jointly with China under the umbrella of ASEAN Regional Forum. Should all these islands be monitored by a Joint ARF Task Force, whose leadership can never be with China? Would a Joint Task Force of the ARF, under the leadership of the USA, be established to ensure implementation of UNCLOS in the South China Sea?

This would blunt the Chinese strength. Further, the Chinese economic coercion needs to be curbed and the bamboo-curtain that it has erected be opened up in a phased manner. For any economic treaty with China, it should be made incumbent by the WTO that concomitant entry has to be provided by China to other countries in a similar manner. It could help resolve the issue in the immediate future. Strengthening extant regional organisations to counter such coercion by a strong nation is the immediate need.

India has to ensure that ‘the Revenge of the Geography’ in the South China Sea stays. It is the first step in ensuring that future threat from China to its Northern borders gets diminished. It would force China in the medium term to resolve the boundary dispute amicably with India and restrict its reach to its ‘near seas’ only, way short of the ‘open seas’ as envisaged by Admiral Liu Huaquing in 1986.