For India, these are crucial times, and it should ensure ASEAN solidarity and a joint response to this imbroglio, a united front of South China Sea claimants (the Philippines, Vietnam, Indonesia, Malaysia, Brunei) negotiating jointly with China under the umbrella of ASEAN Regional Forum. Should all these islands be monitored by a Joint ARF Task Force, whose leadership can never be with China? Would a Joint Task Force of the ARF, under the leadership of the USA, be established to ensure implementation of UNCLOS in the South China Sea?

At this year’s Shangri-La Dialogue on Asian Security, China’s territorial claims in the South China Sea were in sharp focus…

Ever since the major step taken by Hu Jintao in 2006 to call 40 Heads of State of African nations and position China as an alternative source of economic assistance, China has systematically edged forward in various domains covertly and overtly, to challenge the existing World Order. As per Mercatior Institute of China Studies (Merics), China’s foreign policy is working systematically towards a realignment of the international order through establishing parallel structures to a wide range of international institutions.

China has taken on a key role in financing these alternative mechanisms that are designed to increase China’s autonomy vis-à-vis the US-dominated institutions and to expand its international sphere of influence. It currently follows a process of supplementing/complementing existing multi-lateral institutions. Thereafter, it would surely replace the existing order to suit its convenience. The “One Belt, One Road” initiative also appears to be part of this game plan, considering that China herself has burst the myth of its ‘Peaceful Rise’ – as evident in its extreme reactions to the verdict by the Permanent Court of Arbitration against its Nine-Dash Line and its stand-off with the Philippines.

At this year’s Shangri-La Dialogue on Asian Security, China’s territorial claims in the South China Sea were in sharp focus. Admiral Sun Jianguo again represented China at the conference, a position he is uniquely suited for due to his role as the Deputy Chief of the People’s Liberation Army General Staff with the foreign affairs portfolio. On this occasion, Admiral Sun left no room for negotiations on China’s stand on the South China Sea. He said, “I hope to again reiterate that China’s South China Sea Policy has not and cannot change.”

It is necessary to grasp the Chinese Grand-Strategy of Unrestricted Warfare to be able to gauge the inter-linking dimensions and stem this ‘Unpeaceful Rise’ of China…

In addition to ruling out a change in China’s basic position, Sun also hinted that China was seeking to replace or at least supersede regional security organisations, citing a speech by Xi Jinping on April 28, before the Conference on Interaction and Confidence-Building Measures in Asia (CICA), where the Chinese President and Communist Party General Secretary called for, “the building of a new architecture of regional security cooperation that reflects Asian needs” (Xinhua, April 28). Thus, in a step-by-step integrated approach, China seeks to become the sole arbiter for all issues confronting the world, whether in the economic, commerce, defence, diplomatic, political or social domains.

Analysts and policy makers look at each event independent of the other and are thus stymied by their responses, considering that China looks at each as a part of the whole. It benefits from the governance system it has wherein the General Secretary of the CCP controls all facets of the system and dictates the policies that facilitate each other. China seems to have grasped the nuance of Sun Tzu’s famous saying, “The acme of Generalship is to defeat the enemy before war is joined.” With its ‘Unrestricted Warfare’ concept as enunciated in 1999, China has been moving ahead relentlessly with the single-minded purpose of ensuring her rise as the sole super-power at the expense of USA.

China is using military, quasi-military and non-military domains unrelentingly to achieve this end. With a common goal and purpose overarching all the policies in these domains, each step forward in any domain strengthens the rest, akin to a ‘Force Multiplier’, thereby ensuring that the sum as a whole is more than the sum of the parts.

The South China Sea imbroglio is one such event, which is a part of the overall push by China to attain its goal. However, it needs to counter the ‘Revenge of Geography’ (to borrow the quote of Robert Kaplan), to enable it to provide adequate buffer to the Han heartland from its Eastern seaboard. It is, therefore, necessary to grasp the Chinese Grand-Strategy of Unrestricted Warfare to be able to gauge the inter-linking dimensions, and be able to stem this ‘Unpeaceful Rise’ of China. It needs to be a comprehensive strategy to enable the world to be able to withstand economic, political, diplomatic and military outcomes.

Military strategists of China have elaborated a “unified field theory” of war in which the kinetic dimension is no longer dominant…

Unrestricted Warfare: A People’s War in other Dimensions

“Fighting power is but one of the instruments of grand strategy – which should take account of and apply the power of financial pressure, of diplomatic pressure, of commercial pressure and not least of ethical pressure, to weaken the opponents’ will… Unlike strategy, the realm of grand strategy is for the most part terra incognita – still awaiting exploration, and understanding.” —B.H. Liddell Hart, Strategy (1954)

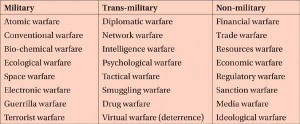

Military strategists of China have elaborated a “unified field theory” of war in which the kinetic dimension is no longer dominant. The most articulate example of such theory to date. remains the manifesto published in 1999 by Colonels Qiao Liang and Wang Xiangsui and translated in English under the somewhat misleading title of Unrestricted Warfare (Chao Xian Zhan, literally ‘War Beyond Rules’ or ‘Beyond-limits Combined War’).

Such a grand-strategy has eight principles, as under:

- Omni directionality – no distinction between what is or is not a battlefield.

- Synchrony – key factors in different space and domains brought to bear within the same designated time period (not necessarily precisely at the same time).

- Limited objectives – creeping forward, within limits based on capabilities at each step.

- Unlimited measures – enlarge scope, space and domains to attain the limited objectives: limited must be pursued in unlimited ways.

- Asymmetry – identify and exploit weak spots and calibrate asymmetrical response to develop any situation as per requirement.

- Minimal consumption – rational designation of objective(s) to make it a step-by-step approach, combine varied dimensional responses to accomplish objective with minimum consumption.

- Multi-dimensional coordination – ensure proper co-ordination between all space and domains of response to accomplish objective. Exploit intangible strategic resources such as ethnic identity, international rules/laws/organisations and socio-cultural/political divides .

- Adjustment and control of the entire process – need feedback and revision at every stage to calibrate resources, space and domains of response based on the enemy’s reactions and thereby ensure initiative is maintained.

Based on the above principles, there are 24 lines of operation identified in the Military, Trans-military, and Non-military domains as under:

The implication is that China has moved on to a People’s War in all domains against all nations including the existing world powers, to ensure that it has an unhindered rise. Considering the shadow institutions it has setup and the desire to supersede the existing security organisations, it is clear that China sees itself as the sole superpower in the long term and is moving towards that goal in a step-by-step approach. What Admiral Sun left unsaid at the Shangri La Dialogue was that superseding the Regional Security Structures, was just the first step.

The implication is that China has moved on to a People’s War in all domains against all nations including the existing world powers, to ensure that it has an unhindered rise. Considering the shadow institutions it has setup and the desire to supersede the existing security organisations, it is clear that China sees itself as the sole superpower in the long term and is moving towards that goal in a step-by-step approach. What Admiral Sun left unsaid at the Shangri La Dialogue was that superseding the Regional Security Structures, was just the first step.

China needs to first secure its heartland from land, sea, space, cyber, economic, commercial, diplomatic, social and air threats…

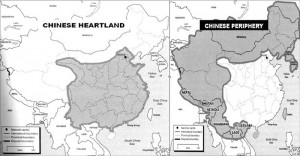

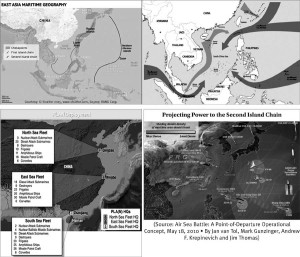

In its march towards a ‘full spectrum’ domination of the world, China needs to first secure its heartland from land, sea, space, cyber, economic, commercial, diplomatic, social and air threats. The South China Sea dominance and subsequent dominance of the East China and Philippines Sea are steps in consonance with this unstated goal. Without the control of the open seas, as enunciated by Admiral Liu Huaqing, (the father of PLA Navy, in his ‘Offshore Defence’ Maritime Strategy in 1986), China would be militarily weak, as the maritime geography of the Eastern Seaboard leaves the ‘Chinese Heartland’ vulnerable to naval attacks.

Currently, the only threat that it faces from the land is from India; but that mainly targets the periphery and not the heartland. East Arunachal, Myanmar, North Vietnam and Laos are critical to China as these provide access to the fringes of its heartland. It appears that the only reason it is dragging the boundary resolution with India is this vulnerability on the Eastern Seaboard. It fears that the intervention by the US Navy, in case of a boundary war with India, would make it lose face with heavy strikes on the Han heartland. So the procrastination with India appears to be its game plan, till it secures itself along the Eastern Seaboard up to the Second Island Chain or till the West Philippine Sea at least.

Towards that end, it started first with its ‘Economic Push’, to ensure that China gets firmly embedded in the world market and ASEAN, as the manufacturing hub, through the 1990s and the early 2000s. Most of the MNCs have their major factories on the Eastern Seaboard of China earmarked as SEZs. At the same time, China has ensured that beyond this, there was no access to this industry into any other part of China.

Towards that end, it started first with its ‘Economic Push’, to ensure that China gets firmly embedded in the world market and ASEAN, as the manufacturing hub, through the 1990s and the early 2000s. Most of the MNCs have their major factories on the Eastern Seaboard of China earmarked as SEZs. At the same time, China has ensured that beyond this, there was no access to this industry into any other part of China.

At the heart of the South China Sea dispute is the “Nine-Dash Line”, Beijing’s claim that encircles as much as 90 per cent of the contested waters…

This economic integration, it correctly opined, would enable it to push the envelope in other domains as the world powers would hesitate to adopt stringent actions fearing an economic backlash. The fall of the Asian Tigers in the late 1990s provided China with a golden opportunity, which it grabbed with both hands. It ensured that China became one of the largest trading partners with each member of the ASEAN and also provided economic support to the economically weaker countries, Laos and Cambodia. It thus worked towards breaking the cohesion of the ASEAN to ensure that future face-off in the South China Sea would ensure no coherent response. This was proved right, considering the muted response to China’s refusal to accept the PCA’s verdict.

Learning from the Tiananmen Square incident, the ‘Colour Revolutions’ in Russia’s periphery and the reach of the social media in its success, it has denied access to them by creating a parallel internet web and social media network in its language that it controls completely. Thus it has ensured the revival of the virtual ‘Bamboo Curtain’ of the Mao era.

Further, it has made inroads into the socio-political domain not only through its diaspora, but also by investing in the extant societal rifts in the various countries thereby weakening their fabric in a slow and steady manner and inhibit their Comprehensive National Power (CNP). In its classic asymmetric response to the various fleet exercises by the US with Japan, Australia, South Korea and India, China floods the area with hundreds of fishing boats and trawlers to impede the exercise. Obviously all are not civilian boats but any physical response could have other repercussions

The South China Sea Imbroglio

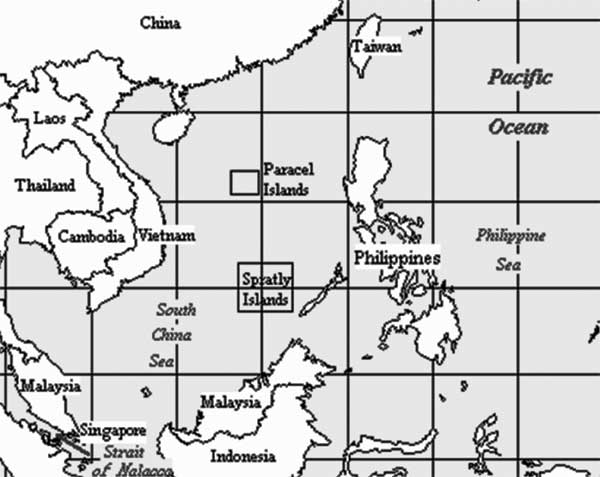

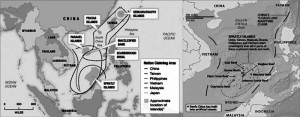

At the heart of the South China Sea dispute is the “Nine-Dash Line”, Beijing’s claim that encircles as much as 90 per cent of the contested waters. The line runs as far as 2,000 km from the Chinese mainland to within a few hundred kilometres of the Philippines, Malaysia and Vietnam. Beijing maintains it owns any land or features contained within the line, which confers vaguely defined “historical maritime rights”.

The Chinese bided their time, integrated into the world market and became one of the largest trading partners with the ASEAN…

The discourse on the South China Sea disputes is understandably laden with emotion. It appeared on a Chinese map as an 11-Dash Line in 1947 as the then Republic of China’s Navy took control of some islands in the South China Sea that had been occupied by Japan during the Second World War. After the People’s Republic of China was founded in 1949, and Kuomintang forces fled to Taiwan, the communist government declared itself the sole legitimate representative of China and inherited all the nation’s maritime claims in the region.

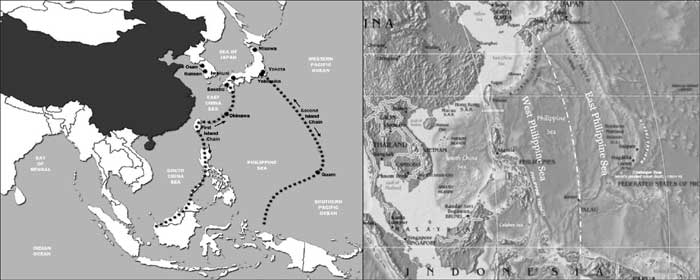

But two “Dashes” were removed in the early 1950s to bypass the Gulf of Tonkin as a gesture to communist comrades in North Vietnam. A look at the choke points along the access routes to the South China Sea, the approaches available to the US naval fleet and the location of its naval fleet, especially the nuclear submarines brings out the issue in stark reality. This is the key for it to achieve its Maritime Strategy as enunciated in 1986 by Admiral Liu Huaquing.

Seen in the backdrop of the approaches available to the US Navy, Hainan Island in the South China Sea, where the PLAN has its nuclear submarine base, is the most critical location. Thus, the importance that China gives to South China Sea, as it struggles to counter ‘The Revenge of Geography’.

As per Admiral Liu Huaquing, PLA Navy needed to develop four capabilities:

As per Admiral Liu Huaquing, PLA Navy needed to develop four capabilities:

- The ability to seize limited sea control in certain areas for a certain period of time

- The ability to effectively defend China’s sea lanes

- The ability to fight outside of China’s claimed maritime areas

- The ability to implement a credible nuclear deterrent.

Bernard D Cole, in his article “The Great Wall at Sea: China’s Navy in the Twenty-First Century”, 2nd edition, (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2010) notes, “…the PLA Navy’s capability to fulfill the requirements of its ‘Offshore Defense’ strategy were to develop along three phases:

On July 12, 2016, a United Nations tribunal ruled that China’s sovereignty claims over the South China Sea and its aggressive attempts to enforce them violate international law…

Phase 1: To be achieved by 2000, during which time the PLA Navy needed to be able to exert control over the maritime territory within the First Island China, namely the Yellow Sea, East China Sea and South China Sea — a goal that Cole argues China has yet to fully achieve. But the deployment of Chinese weapons on its Eastern Seaboard and its effective reach belies this notion.

Phase 2: To be achieved by 2020, when the Navy’s control was to extend out to the Second Island Chain. It is for this phase that China wants to secure the South China Sea and deploy its aircraft and missiles on the artificial islands created to ensure effective dominance up to the Second Island Chain or at least till the West Philippine Sea. This will enable it to gain unhindered access to the Indian Ocean – the Phase most critical for India as China would then be aggressive against it along both its Northern and Maritime borders, without fear of intervention by the US Navy as it would be fighting well beyond its maritime boundaries with them and be able to defend its sea lanes of communications. It would, thereby, have fulfilled three out of the four capabilities as listed by Admiral Liu Huaquing.

Phase 3: To be achieved by 2050, by which time the PLA Navy is to evolve into a true global navy and launch itself on to the ‘open seas’. By then the development of the SSBN fleet would also have been completed and the PLAN would be in a position to provide effective nuclear deterrence.

Before pushing aggressively in the South China Sea and learning its lessons from the earlier push in the late 1980s and early 1990s, China evolved its ‘Unrestricted Warfare’ by going beyond conventional war and entering into domains that are quasi-military and non-military. While the 1980s had a different geo-strategic impulse, post First Gulf War, China realised that the methods of pure military deterrence were passé and the need was for economic, commercial, diplomatic, socio-political deterrence – their concept of ‘Unrestricted Warfare’ akin to the US concept of ‘Full Spectrum Dominance’.

India needs to realise that South China Sea is but a step towards China’s ultimate goal of being the sole arbiter in Asia and later, the world…

Thus, the Chinese bided their time, integrated into the world market and became one of the largest trading partners with the ASEAN. Concurrently, China developed and deployed its missiles, new generation fighters, ships, nuclear submarines and cruise missiles on its Eastern Seaboard thereby ensuring effective weapons coverage up to the First Island Chain and some coverage beyond.

Having achieved it by 2010-2012, China now began its assertive push into the South China Sea by reclaiming rocks and atolls, and converting it into islands to expand its military presence in the area. To guard its Eastern Seaboard, China needs to control the Senkaku, Pratas, Paracel and Spratly Islands and the Scarborough Shoals (the case referred to PCA by the Philippines), and these are where the Chinese push has come about over the last few years.

The Way Ahead

On July 12, 2016, a United Nations tribunal ruled that China’s sovereignty claims over the South China Sea and its aggressive attempts to enforce them violate international law. The Hague-based Permanent Court of Arbitration found that China’s main claim to the sea, represented by its notorious “Nine-Dash Line” map, has “no legal basis.” It further slammed China’s frequent claims to “historic” rights, confirming that these do not fly under the UN Law of the Sea Treaty and that there is “no evidence that China had historically exercised exclusive control over the waters or their resources.” China has said it will not accept a ruling against it in a key international legal case over strategic reefs and atolls that Beijing claims would give it control over disputed waters of the South China Sea.

The Chinese President, Xi Jinping, said China’s “territorial sovereignty and marine rights” in the seas would not be affected by the ruling, which declared large areas of the sea to be neutral international waters or the Exclusive Economic Zones of other countries. He insisted China was still “committed to resolving disputes” with its neighbours. A clever policy, as individually each country could succumb to the lure of Chinese investment, as is evident from the responses of the Philippines President Rodrigo Duterte, who took office June 30 promising better relations with China. He wants bilateral talks, Chinese investment and joint resource development in the South China Sea.

The Chinese President, Xi Jinping, said China’s “territorial sovereignty and marine rights” in the seas would not be affected by the ruling, which declared large areas of the sea to be neutral international waters or the Exclusive Economic Zones of other countries. He insisted China was still “committed to resolving disputes” with its neighbours. A clever policy, as individually each country could succumb to the lure of Chinese investment, as is evident from the responses of the Philippines President Rodrigo Duterte, who took office June 30 promising better relations with China. He wants bilateral talks, Chinese investment and joint resource development in the South China Sea.

The UN may have to do some soul-searching on whether China should be a part of it and gain from its Institutions, if it is not ready to abide by International Laws…

By stressing that, “India supports freedom of navigation and over-flight and unimpeded commerce based on the principles of international law, as reflected notably in the UNCLOS,” the MEA statement was seen as chiding China. Emphasising India’s specific national interest in the issue, it added, “States should resolve disputes through peaceful means without threat or use of force and exercise self-restraint in the conduct of activities that could complicate or escalate disputes affecting peace and stability.” The demand for “utmost respect,” the assertion of India’s vital interest in maintaining “freedom of navigation and over-flight rights under UNCLOS” and aversion to “activities that complicate or escalate disputes” – all implied strong criticism of Beijing’s intention to reject the tribunal’s verdict and continue as before.

Is that enough? India needs to realise that South China Sea is but a step towards China’s ultimate goal of being the sole arbiter in Asia and later, the world. That status it can achieve only if its Navy can get unrestrained access to the Indian Ocean in the first phase and the Pacific and Atlantic thereafter. Control over the South China Sea is critical towards this step and hence the vitriolic response in the Chinese media against this judgment.

The response has to be a joint concerted push in all domains, military, trans-military and the non-military domains. Plans need to be made by the leading economists on a step-by–step approach to counter the Chinese economic creep and overcome the impact on world economy should China respond vehemently. At the same time, maybe the UN may have to do some soul-searching on whether China should be a part of it and gain from its Institutions, if it is not ready to abide by International Laws and norms to which it is a signatory.

Chinese economic coercion needs to be curbed and the bamboo-curtain that it has erected be opened up in a phased manner…

Is there a case to re-look the various shadow institutions that China has created and put certain rules and curbs in place to deny Chinese economic arm-twisting of the under-developed countries? Should there be such shadow organisations or re-cast and strengthen existing bodies? India needs to ensure a joint calibrated response to this Chinese thrust. Even as it seeks to gain control of the South China Sea and is procrastinating in resolving the land boundary, it is keen to enter the Indian market, financial market et al, while it blocks all attempts by the Indian entrepreneurs’ in entering the Chinese markets. Reciprocity has never been a part of the Chinese push, as these thrusts are all a part of its ‘Unrestricted Warfare’. Hence it has the fear of a blowback in its backyard akin to what it aims to achieve in other countries.

In what manner can the ARF ensure a joint military and trans-military response to China’s aggressive stance of claiming the South China Sea as its exclusive domain? Would the arming of the ASEAN countries with THAAD, cruise missiles, anti-ship missiles and UCAVs prove beneficial in the long run? Should all ASEAN countries also follow an asymmetric response like the Chinese and inhibit the artificial islands and PLAN movement with hundreds of fishing boats and trawlers? However, before such a step, they would need to ensure a quick joint response to any PLAN adventurism against it.

For India, these are crucial times and it should ensure ASEAN solidarity and a joint response to this imbroglio, a united front of South China Sea claimants (the Philippines, Vietnam, Indonesia, Malaysia, Brunei) negotiating jointly with China under the umbrella of ASEAN Regional Forum. Should all these islands be monitored by a Joint ARF Task Force, whose leadership can never be with China? Would a Joint Task Force of the ARF, under the leadership of the USA, be established to ensure implementation of UNCLOS in the South China Sea?

This would blunt the Chinese strength. Further, the Chinese economic coercion needs to be curbed and the bamboo-curtain that it has erected be opened up in a phased manner. For any economic treaty with China, it should be made incumbent by the WTO that concomitant entry has to be provided by China to other countries in a similar manner. It could help resolve the issue in the immediate future. Strengthening extant regional organisations to counter such coercion by a strong nation is the immediate need.

India has to ensure that ‘the Revenge of the Geography’ in the South China Sea stays. It is the first step in ensuring that future threat from China to its Northern borders gets diminished. It would force China in the medium term to resolve the boundary dispute amicably with India and restrict its reach to its ‘near seas’ only, way short of the ‘open seas’ as envisaged by Admiral Liu Huaquing in 1986.