India’s tryst with contemporary terrorism started with the birth of the Khalistani movement in Punjab, which was followed by insurgency in the Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir. On the other hand, Maoist insurgency with a pan-Indian presence and insurgency in India’s north-east has been one of the teething issues seen as an impediment to the peace and tranquillity in these regions. While the Maoists have been in existence since the 1970s, insurgency in the North East, such as the Naga insurgency, is a direct legacy of the British rule. Most of the other insurgent groups, like the United Liberation Front of Assam (ULFA), are at least three decades old and have survived repeated government onslaughts and internecine conflicts.1

India’s tryst with contemporary terrorism started with the birth of the Khalistani movement in Punjab, which was followed by insurgency in the Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir. On the other hand, Maoist insurgency with a pan-Indian presence and insurgency in India’s north-east has been one of the teething issues seen as an impediment to the peace and tranquillity in these regions. While the Maoists have been in existence since the 1970s, insurgency in the North East, such as the Naga insurgency, is a direct legacy of the British rule. Most of the other insurgent groups, like the United Liberation Front of Assam (ULFA), are at least three decades old and have survived repeated government onslaughts and internecine conflicts.1

The prolonged existence of these terror and insurgent groups has been possible inter alia because of their financial strength, which feeds the organisations as well as their operational requirements. Often, these groups need finances to underwrite costs associated not only with conducting terrorist attacks (operational costs) but also with developing and maintaining a terrorist organisation and its ideology (organisational costs).2 Funds are required to promote militant ideology, pay operatives and their families, arrange for travel, train new members, forge documents, pay bribes, acquire weapons and stage attacks. For instance, it is estimated that 10 per cent of the annual income of al-Qaeda went to operational planning and execution while 90 per cent was mainly used for the network infrastructure, facilities, organisation, communication and protection.3

…in line with their new financial objectives, financial portfolios of these groups have relied more on nontraditional and criminal revenue streams, from kidnap for ransom and extortion…

Terror groups in India and some of the bigger known groups, like ULFA and the Nationalist Socialist Council of Nagaland (NSCN), have relied upon traditional sources of finances, like state sponsorship and narcotics trade, in the 1980s.4 However, recent trends point to increased incidence of reliance on internal activities with an aim to achieve selfsufficiency in their funding activity. Hence, in line with their new financial objectives, financial portfolios of these groups have relied more on nontraditional and criminal revenue streams, from kidnap for ransom (KFR) and extortion, recently. However, it has to be mentioned that KFR and extortion are not new revenue streams but have been in usage by groups such as the NSCN since the late 1980s concomitantly, with their revenue streams from state sponsorship and narcotics.5 This increasing reliance on KFR and extortion by all these groups to augur their group economics has placed a huge burden on the common man and his economics, especially in the north-east region. This paper would attempt to highlight the KFR operations adopted by the Indian terror and insurgent groups to finance their illegal activities.

Organised criminal groups in India have been involved in KFR and extortion activities. However, this research would limit its focus and scope only to the KFR operations by larger terror and insurgent groups, like the Maoists and other north-east groups. However, any meaningful research has to be supported by credible evidentiary data, which is not available in India. The only available database related to KFR incidents in India is provided by the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB), which provides data differentiating between KFR operations based on motives like revenge, ransom and sex. It, however, does not give granular information on KFR operations conducted individually by criminal gangs and terror groups. Moreover, the information supplied is not in its entirety as ransom payment details are not available in the open domain. Absence of complete information on KFR operations pertaining to terror groups adds to the existing complexities and is one of the challenges in conducting this analysis in the Indian context. However, information from other multiple open source databases, like South Asian Terrorism Portal (SATP),15 which could to some extent assist in assessing the ground realities, have been used to study the KFR operations pertaining primarily to the groups in the North East.

India has had its share of high-profile KFR episodes in the past with political objectives. Rubaiya Sayeed, daughter of Mufti Mohammed Sayeed, the Indian home minister in 1989, was kidnapped by militants belonging to the Jammu & Kashmir Liberation Front. They demanded the release of five militants, namely Abdul Hamid Sheikh, Sher Khan and three other extremists facing charges of anti-national activities – Noor Mohammad Kalwal, Altaf Ahmed and Javed Ahmed Jargar – who were later released by the Indian government.16 The capitulation of the Indian government became a trigger for insurgency ascent in Jammu & Kashmir and set a precedent for other episodes in the future.17

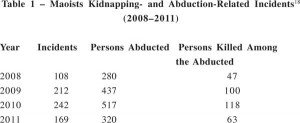

From 2008 to 2011, a total of 1,554 persons were kidnapped by the Maoists in different parts of India…

On 24 December 1999, five Pakistani terrorists associated with Harkat-ul-Jihad-al-Islami (HUJI) hijacked an Indian Airlines flight from Kathmandu to Kandahar, demanding the release of three Pakistani terrorists held in Indian jails. After prolonged negotiations with the Taliban, India’s minister of external affairs, Jaswant Singh, personally accompanied three terrorists to the Taliban in Kandahar in exchange for the surviving passengers. These kidnapping episodes represent the kidnapping-for-swap typology consistent with or similar to the trends prevalent among religiondriven terror groups during their KFS operations observed elsewhere globally.

The insurgent groups, on the other hand, also use KFR operations and extortion widely to extract both political and financial gains. The Maoists, in particular, have kidnapped government officials, private individuals and contractors in areas where they had presence. From 2008 to 2011, a total of 1,554 persons were kidnapped by the Maoists in different parts of India (see Table 1). Out of these, 328 persons were killed by the Maoists and the rest released.

It is imperative to mention at this juncture that not all Maoist kidnappings pertain to ransom demands as Maoists are known to abduct and kill informers who act against them. However, considering the high release percentage (79 per cent of the hostages are released) of the hostages kidnapped by the Maoists, it would be logical to assume that the government or the concerned stakeholders would have met the demands either fully or partially. However, past experience and prudence dictate that not all political demands can be met on all occasions, perceptibly pointing to the presence of financial ransom or demands in some of the cases if not all.

It is imperative to mention at this juncture that not all Maoist kidnappings pertain to ransom demands as Maoists are known to abduct and kill informers who act against them. However, considering the high release percentage (79 per cent of the hostages are released) of the hostages kidnapped by the Maoists, it would be logical to assume that the government or the concerned stakeholders would have met the demands either fully or partially. However, past experience and prudence dictate that not all political demands can be met on all occasions, perceptibly pointing to the presence of financial ransom or demands in some of the cases if not all.

…the only fundraising activities with minimum investment, minimum exposure and maximum returns were KFR and extortion operations.

However, post 9/11, with their traditional sources of funding drying up due to the war on terrorism, Indian terror groups took to KFR, which was again consistent with the similar operations of other groups, like al- Qaeda and its affiliates. The period post 9/11 witnessed the obliteration of traditional hierarchical terror groups around the world, which led to the emergence of a new phenomenon, called ‘new terrorism’. Groups under this new phenomenon were characterised by flat structures and autonomous modules with indigenous membership. Hence, these small groups had to necessarily diversify into local sources of funding in the areas of their operations using local resources. Given these constraints, the only fundraising activities with minimum investment, minimum exposure and maximum returns were KFR and extortion operations. For instance, the Indian Mujahedeen (IM), which closely resembles the characteristics associated with ‘new terrorism’ in India, uses KFR operations to fund its operations.19

The IM’s foray into criminal activities began when one of its key members, Riyaz Bhatkal, came in contact with Asif Raza Khan through another gangster, Aftab Ansari.20 Asif Raza Khan was, however, killed in a shootout with the Gujarat police in 2002. His brother, Amir Raza Khan, set up the Asif Raza Commando Force, a fundamentalist group. Amir Raza Khan, who is linked to terror operations, including an attack on the US cultural centre in Kolkata, allegedly provided passports and funds to facilitate the movement and training of several IM members in Pakistan through Riyaz Bhatkal.21 Amir Raza Khan is now an important member of IM after merging with IM (possibly part of the core leadership).

Aftab Ansari, who is part of the Asif Raza Commando Force and the operational mastermind behind the attack on the US cultural centre in Kolkata in 2002, was instrumental in raising around Rs. 60 crore from abduction, extortion and kidnapping of Indian businessmen. For instance, the 2001 abduction of Kolkata business baron Partha Roy Burman and Rajkot-based jeweller Bhaskar Parekh yielded Rs. 7 crore in total for the Ansari gang.22 It is now known that Ansari paid USD 1,00,000 out of the Partha Roy ransom amount23 to Omar Sheikh (the prime accused in the Daniel Pearl killing case and one of the terrorists released by the Indian government in the IC 814 hijacking case). This money, however, ended up with Mohammed Atta, the leader of 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center in 2001.24 Given the linkages and influence, it would not come as a surprise for the erudite to assess the IM’s involvement in extortion operations.

A few years back, Assam became the kidnap capital of India. The state recorded 3,250 abductions in 2010; 3,785 cases in 2011; 3,812 cases in 2012 and 4,113 abductions in 2013.

In 2002, Mumbai police records show criminal proceedings were first initiated against Riyaz for an extortion-related attempt to murder Kurla-based businessman Deepak Farsanwalla.25 There have been only isolated incidents of KFR operations by terror groups like Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT) and the IM that have been documented. However, recent open source reports indicate that an arrested LeT operative Abdul Subhan had planned to kidnap corporate leaders in India to finance their activities.26

On the other hand, insurgent groups in the North East use KFR operations solely to finance their campaigns. Groups like ULFA, NSCN factions, and other smaller groups have adopted KFR operations.

A few years back, Assam became the kidnap capital of India. The state recorded 3,250 abductions in 2010; 3,785 cases in 2011; 3,812 cases in 2012 and 4,113 abductions in 2013. However, not all kidnappings pertain to terror and insurgent groups. According to SATP, Assam’s forest minister Rockybul Hussain has stated that, altogether, 191 persons were abducted by different insurgent outfits in Assam from 2011 to 2013. Mr. Hussain further disclosed that between 2006 and 2011, there were 456 cases of abduction in the state. In 2012, the state police arrested 620 members of various insurgent outfits for indulging in kidnapping and extortion.

Insurgent groups like the ULFA anti-talk faction, or ULFA (Independent); the National Democratic Front of Bodoland (NDFB) antitalk faction; Karbi People’s Liberation Tiger (KPLT) and the Kamtapur Liberation Organisation (KLO) are all known to indulge in KFR operations. The most prominent among them was ULFA.