In the wake of President Yahya Khan’s threats, India had considered the various courses open to Pakistan on the Western front. Many possibilities were considered: an attack across the CFL in the hilly areas of Jammu & Kashmir, or against Chhamb, or the Samba-Jammu or Samba-Pathankot sub-sectors. An offensive in the Punjab plains and forays into Rajasthan were also envisaged. However, due to the commitment on the Eastern front and the possibility of intervention by China, the Indian Government had decided that a posture of offensive defence would be maintained in the West.

As in 1965, two commands shared the responsibility for India’s Western borders. The Western Command, under Lieutenant General K.P. Candeth, was responsible for the whole area extending Northward from Anupgarh, on the edge of Rajasthan, to the furthest limit of the CFL in Jammu & Kashmir. It was also responsible for the India-China border in Ladakh.1 The border running through the Thar Desert, in Rajasthan, and along the Rann of Kutch, in Gujarat, was under the Southern Command commanded by Lieutenant General G. G. Bewoor (later General G.G. Bewoor, PVSM, COAS) .

Click to buy: Indian Army After Independence

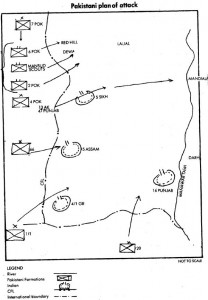

In this theatre, Pakistan had near parity with India in armour and artillery, while the latter had superiority in infantry (for the order of battle on the two sides, see Appendix 3). West Pakistan had ten infantry divisions, a few independent infantry brigades, two armoured divisions, and two independent armoured brigades. Of these formations, their 12 Infantry Division, with a large paramilitary force under command, was deployed in the Northern sector of Occupied Kashmir, while they had their 23 Infantry Division (of four infantry brigades) deployed against Chhamb. These two divisions also included seven POK Brigades, which were considered as good as regular Pakistan Army troops, especially when employed in Jammu & Kashmir. Their 1 Corps, with Headquarters at Sialkot/Kharian, was responsible for the area opposite Chhamb to Dera Baba Nanak, between the Chenab and Ravi Rivers. Of West Pakistan’s three corps, this was the strongest in armour and infantry. It had 6 Armoured Division (less two regiments, which were with 23 Division), 8 Independent Armoured Brigade (of four regiments) and 8, 15 and 172 Infantry Divisions. Of these 6 Armoured and 17 Infantry Divisions were uncommitted and therefore in reserve. 8 Independent Armoured Brigade was committed to act as a mobile strike force in Shakargarh at the limit of penetration.

Pakistan had near parity with India in armour and artillery, while the latter had superiority in infantry.

Pakistan’s 4 Corps, with Headquarters at Lahore, was responsible for the Lahore-Amritsar axis and the area opposite Khem Karan. It had two infantry divisions (10 and 11). Their 2 Corps was responsible for the area down South up to Fort Abbas with its Headquarters at Multan. It had one infantry division (33) and two infantry brigade groups. The sector opposite India’s Southern Command was under their 18 Infantry Division, which had two regiments of armour. Pakistan’s GHQ reserve, consisting of 1 Armoured Division and 7 Infantry Division, was held in the Okara-Montgomery area, close to their 2 Corps.

Candeth had three corps. In the North, 15 Corps, under Lieutenant General Sartaj Singh, was deployed in Jammu & Kashmir. It had five infantry divisions (3, 19,25, 10 and 26) and one independent armoured brigade (3) under command. The area from Anupgarh to Dera Baba Nanak (North of Amritsar) was the responsibility of 11 Corps under Lieutenant General N.C. Rawlley. This Corps had three infantry divisions (15, 7 and Foxtrot Sector [a divisional level area command]) and one independent armoured brigade (14). North of Dera Baba Nanak, the Indo-Pak border takes a plunge to the East, forming a bulge that reaches close to Pathankot, India’s base for land-communications with Jammu & Kashmir. This bulge, with the Pakistani town of Shakargarh at its centre, was a source of worry to the Indian command. Its neutralization was made the responsibility of 1 Corps, commanded by Lieutenant General K.K. Singh, and the main strike force of Western Command. Of the Corps’ three infantry divisions, only one was stationed in the vicinity of the bulge in normal times. The rest of its strength was held in Central and Southern India and was moved to Punjab in October after Pakistan had begun a build-up on the border. Indian Army Headquarters reserves, comprising 1 Armoured Division and 14 Infantry Division, were positioned South of the Sutlej.

Accounts published after the termination of hostilities spoke of a sharp division within the Pakistani high command. It was said that one group had been for an all-out offensive, while the second group favoured preliminary operations by holding formations. These operations would fix the Indians and divert their attention, so as to facilitate the subsequent launching of the main offensive. Ultimately, the views of the second group prevailed.

Pakistan began the war without ultimatum or warning by launching air-strikes on Indian airfields.

Pakistan had the advantage of choosing the time and place of her attacks. The Indian high command could only plan measures to counter Pakistan’s designs, as perceived from the placement of her forces. Both sides knew fairly accurately the general dispositions of each other. The Indian aim was to draw out Pakistani reserve formations in such a manner that they should not be in a position to launch a major offensive against India. Towards this end, limited offensive operations were planned as under:

- An advance by 1 Corps into the Shakargarh Bulge with a view to capturing Zafarwal, Dhamthal and Narowal. The Corps was subsequently to secure the line Marala – Ravi Link Canal- Degh Nadi and later take Pasrur.

- A two-pronged move by 15 Corps, with 10 Infantry Division advancing North of the Chenab towards Tanda and Gujarat and 26 Infantry Division advancing South of that river to threaten Sialkot.

- A feint towards Qila Sobha Singh by simulating a crossing over the Ravi in the general area of Gill Ferry.

The rest of the Western Command was to maintain a posture of offensive defence. In case 1 Corps’ offensive succeeded in diverting Pakistan’s GHQ reserve to the Shakargarh Bulge, Candeth was to launch the Indian reserve, together with other troops that could be mustered from the holding forces at the point of thrust, across the Sutlej so as to secure Pakistani territory up to the line Raiwind-Rajajang-Luliani, South-West of Lahore.3

In the event, neither side could launch its reserves to deliver what each had planned as its coup de main. The Pakistani command kept dithering till the declaration of unilateral cease-fire by India, while the Indian advance bogged down before 1 Corps could capture its initial objectives.

Pakistan began the war without ultimatum or warning by launching air-strikes on Indian airfields. At about 2000 hours, Pakistani artillery shelled Indian border posts, which were mostly manned by the Border Security Force (BSF). The shelling was followed by infantry attacks. These came mostly in company-strength and were repelled in most cases. There were, however, certain objectives over which the Pakistanis expended much more effort.

Chhamb

One of the Pakistanis’ main objectives was Chhamb in the 10 Division Sector of 15 Corps. In 1965, the Pakistanis had succeeded in capturing this place with a surprise attack. There should have been no surprise element in 1971, yet they succeeded again. This time they caught 10 Division off balance.

| Editor’s Pick |

This division, under Major General Jaswant Singh, was deployed for the offensive already mentioned. It was fairly well-equipped, having as it did four infantry brigades, two regiments of armour (9 Horse and 72 Armoured Regiment), two Engineer regiments, six regiments of artillery (two medium, three field and one light), besides elements of air defence and locating artillery and the usual ancillary units. The division also had a para commando group (from 9 Para) and a squadron equipped with anti-tank guided missiles. Of his infantry, Jaswant Singh deployed 28 Brigade in the hill sector North and North-East of Chhamb, while 191 Brigade held the firm base in the plains West of the Manawar Tawi. Covering troops held positions supporting BSF posts on the border. The first phase of the attack was to be put in by 68 Brigade, held around Akhnur. The division’s fourth brigade (52) was had near Jaurian.

The deployment of the division was based on the assumption that the commencement of its offensive would by itself ensure the defence of the Chhamb-Akhnur area. This was unfortunate. The assumption disregarded the basic principle that it is always the responsibility of a commander to ensure the security of his own force and what he is required to defend in the first instance. As it was, the bulk of 10 Division’s troops had been pulled out of their defences into concentration areas to prepare for the offensive. This should actually have happened after the main offensive of 1 Corps had got under way, enemy reactions observed and it was reasonably certain that a threat to Chhamb no longer existed.

On 30 November, the Indian Government received an intelligence report that Pakistan would attack in the West in the next few days. This information was conveyed to the Army Chief with a directive that Indian troops on that front would remain on the defensive until permission was given to go on the offensive. Thanks to the lethargy in passing down this information, it reached 10 Division on the evening of 1 December. It was only on 2 December that a co-ordinating conference was held at Jammu and certain moves were ordered. In the event, no major adjustment was made in the deployment of the division and only marginal changes were effected. Efforts were made to strengthen the existing minefields and lay new ones. However, in the Barsala-Jhanda area, South-West of Chhamb, through which 10 Division was to have attacked, a dummy minefield was left.

On the evening of 3 December, Major General Jaswant Singh was with Brigadier (later Lieutenant General) R.K. Jasbir Singh, Commander 191 Brigade, at the latter’s Headquarters at Chhamb. Of the brigade’s four infantry battalions, three covered the CFL from the Manawar village-Jhanda area, in the South, to Mandiala, in the North (see Fig. 11.2). One battalion held positions East of the Manawar Tawi. A squadron of 9 Horse was deployed West of the river, and guided missiles covered the crossings over it. One battalion of 28 Brigade was holding the Dewa-Ghopar axis in the foothills North of Mandiala. The new defences, occupied after the warning from Army Headquarters, had been hastily prepared due to lack of time and stores. About 1900 hours a general alert was sounded after the corps commander rang up and told of the Pakistani air-strikes. A massive artillery bombardment of border posts began shortly before 2100 hours. Then, around 2130 hours, came simultaneous attacks all along the line. Indian troops stood their ground except at one or two places.The attack was mounted by Pakistan’s 23 Division. Captured documents and prisoners of war later revealed that the Pakistanis’ aim here was to secure Indian territory up to the East bank of the Manawar Tawi. Major General Iftikhar Khan, the Divisional Commander, showed skill and determination in carrying out his mission. He decided to capture Chhamb with an outflanking move from the North. After the cease-fire it came to be known that he employed four infantry brigades, supported by an armoured brigade and eight regiments of artillery for the operation. The additional resources given to him were 2 (ad hoc) Independent Armoured Brigade, 66 and 111 Infantry Brigades and sizeable corps’ artillery reiriforcing his own (see Fig. 14.1). He used two of his own brigades to hold his firm base.

Click to buy: Indian Army After Independence

Indian intelligence sources had indicated the approximate location of Pakistani concentrations but the presence of that much artillery and armour was not known. It is probable that after the initial attacks on the night of 3/4 December more enemy units were quickly brought forward under cover of the noise and fog of battle. The Pakistani base at Kharian was only about 50 kilometres away.

The enemy had occupied the high ground at Mandiala and brought the troops on the Eastern end of the bridge under machine-gun fire.

On 4 December, the enemy attacked many Indian positions with armour and infantry. On the Dewa-Ghopar axis, in the North, six Pakistani tanks were knocked out. However, by midday, Mandiala North had fallen. That day several localities South and South-West of Chhamb were also overrun or ordered to withdraw.

During the afternoon, efforts were made to reinforce 191 Brigade but these reinforcements were sent piecemeal and could not save Chhamb. A squadron of 72 Armoured Regiment was placed under the brigade and the para commando group and a troop of 9 Horse were deployed on the Eastern side of the Mandiala Bridge to block the enemy’s advance towards Jaurian. To retake Mandiala North, 7 Kumaon and a squadron of 72 Armoured Regiment were ordered forward from Akhnur (68 Brigade). During the night, however, while this group was on its way, its mission was changed. It was told that its task now would be to guard the East bank of the Manawar Tawi in the area of the bridge. The change was perhaps due to the failure of a counter-attack against Mandiala North that had been put in at 2020 hours.

The cavalier manner in which the situation was being handled can be seen from the composition of the force employed for that counter-attack: about 70 men lifted from an area South of Chhamb, a detachment of tanks and a field battery. The enemy had occupied the high ground at Mandiala and brought the troops on the Eastern end of the bridge under machine-gun fire. Around 0300 hours on 5 December, a company of enemy infantry and a troop of tanks scrambled across the Sukhtau Nulla, a tributary of the Manawar Tawi that joins it North of the bridge. The para commandos and 9 Horse were wide awake and scattered the enemy with ease. But this was only a probe.

A brigade attack came an hour and a half later when Pakistan’s 47 Punjab attacked after a heavy artillery concentration. The tiny force at the bridge held its ground but an overflow of the assault went on to 216 Medium Regiment gun area and wagon lines and the enemy succeeded in disabling six of its guns4 and killing some men in the wagon lines. The assaults was beaten back by the depth battery and 39 Medium Regiment firing over open sights. This regiment was deployed a short distance East of the para commandos. The second medium regiment of the division (39th) was also deployed about 1,000 metres further East.The enemy’s 47 Punjab was soon followed by 13 Azad Kashmir Battalion. Meanwhile, the main body of 7 Kumaon had come under heavy shelling when moving to Mandiala Crossing after debussing at Kachreal. Caught in the open, the battalion suffered heavily and four of its officers (including the commanding officer) were wounded. With the arrival of the second enemy battalion, pressure on the Indian position increased. The para commandos lost some ground and the Kumaonis were in disarray. There was confused fighting for some time. Enemy infantry tried to capture the tanks on the bridge but their efforts were foiled by the crew, who managed to keep their cool.

At this stage, some enemy armour that had been standing by under cover of the Sukhtau Nulla moved out to link up with its infantry under the impression that the latter had already secured a bridgehead. As they came up the embankment, they were easy targets. Within seconds five of them were written off while the remainder managed to get away.

After the rebuff in the Kachreal-Mandiala Crossing area, the enemy had shifted its attention South-West of Chhamb.

The situation eased when the Commander of 68 Brigade reached the scene on the morning of 5 December with a company of 9 Jat mounted on two troops of tanks from 72 Armoured Regiment. The remnants of the enemy between Mandiala Crossing and Kachreal Heights were cleared. During the mopping up, about 180 Pakistani dead were counted. Among the prisoners was Lieutenant Colonel Basharat Ahmed, the commanding officer of 13 Azad Kashmir Battalion.

A reorganization on the morning of 5 December limited 191 Brigade’s responsibility to the area West of the Manawar Tawi. That day the rest of 9 Jat moved up from Akhnur and was made responsible for the three crossings over the river South of Mandiala Crossing: Darh, Chhamb and Raipur. After the rebuff in the Kachreal-Mandiala Crossing area, the enemy had shifted its attention South-West of Chhamb. That night, after bitter fighting, it succeeded in taking three localities in the area. Though a counter-attack soon drove it back, the situation was causing considerable concern. The artillery deployed West of the river was moved East of it and a battalion (less a company) from 68 Brigade was sent forward to reinforce 191 Brigade.

On 6 December, the enemy increased its pressure South-West of Chhamb as it had discovered that the minefield in the area was a dummy. During the afternoon, it captured Ghogi and Barsala after repeated attacks. By evening, Mandiala South had also fallen. Quickly exploiting this success, it pushed East. Attempts to readjust the line proved futile and 191 Brigade was ordered to withdraw across the river after last light. The Mandiala bridge was blown up at 2330 hours after the last Indian troops had crossed over.

| Editor’s Pick |

As in 1965, the Pakistanis chose to pause after this initial success. Iftikhar Khan did not pursue 191 Brigade across the Manawar Tawi straightaway. This gave Indian troops the time to strengthen their defences and the enemy lost the chance of establishing itself East of the river.

It was on the night of 7/8 December that the Pakistanis tried to get a foothold East of the river, only to be thrown back. However, on the afternoon of 8 December, Dewa, in the hill sector, fell. On the night of 9/10 December, the enemy made a second and more determined attempt to come East of the river. It put in a brigade attack, supported by armour, against 9 Jat. The battalion fought hard to hold its ground but superior numbers prevailed and the enemy succeeded in taking the crossings at Darh and Raipur. However, timely reinforcement of the area prevented it from expanding and building up its bridgeheads. Some of its follow-up echelons were shot up and its tanks were unable to give much support to the infantry due to bad going. The next morning, a counter-attack was launched by 3/4 Gorkha Rifles (ex 52 Brigade), with some armour in support. However, when the tanks bogged in the soft ground, the infantry also dug in about 900 metres short of Darh.

Indian troops fought well at Chhamb. One cannot, however, help saying that the higher commanders did not acquit themselves too well.

Around noon, Lieutenant General Sartaj Singh arrived on the scene and ordered a counter-attack to roll up the enemy bridgeheads from North to South. The Darh Crossing was retaken by 5/8 Gorkha Rifles, supported by a squadron from 72 Armoured Regiment. The Raipur Crossing was recaptured with a two-pronged attack by 3/4 Gorkha Rifles and a company of 10 Garhwal Rifles. The operation was over around midnight. Dawn revealed the fierceness of the struggle. The whole area was littered with Pakistani dead and six of their tanks lay abandoned.

This was the last Pakistani attempt to gain a foothold East of the Manawar Tawi. Soon after this action the Pakistani high command withdrew the additional resources it had brought into this sector. Major General Iftikhar Khan was killed in a helicopter crash on 10 December. Surprisingly neither 10 Division nor 15 Corps exploited the enemy’s inactivity and the depletion of its resources. From 11 December till the cease-fire no worthwhile task was undertaken by 10 Division to regain lost territory. .

Indian troops fought well at Chhamb. One cannot, however, help saying that the higher commanders did not acquit themselves too well. When the warning regarding the enemy attack was given, they did not make all-out efforts to strengthen the defences, or redeploy their resources. An even greater error was to ignore direct observation reports being sent in a steady stream by forward troops. Caught off balance, they did little to rectify the faulty deployment. The situation demanded bold action but the divisional commander contented himself with moving battalions and companies or squadrons, instead of dealing with brigades and armoured regiments. This led to ineffective and indecisive command and control. The corps commander took a firm hand only on 10 December. On the other hand, the enemy commander showed commendable flexibility. Having achieved surprise by using the Northern approach, he switched to the South when he found himself firmly checked at Mandiala Crossing.

The poor showing in this sector warranted a thorough investigation to avoid a repetition of the errors that led to the loss of Chhamb. But no such action appears to have been taken, and India lost this valuable territory under the Simla Agreement.

As in 1965, Indian casualties in this sector were heavy. Of the 440 killed, 23 were officers and 20 JCOs. Among the 723 wounded, 36 were officers and 35 JCOs. The missing and the prisoners numbered 190: Five among them were officers and three JCOs. Losses in equipment included 17 tanks and 10 guns destroyed and 1 tank and 12 guns damaged. Pakistan’s casualties were not announced but Major General Fazal Muqueem Khan has confirmed in his book, Pakistan’s Crisis in Leadership, that they were heavy.The Pakistan Air Force was quite active in this sector. The Indian Air Force began its support to ground troops on 4 December. It was in low key to start with but was later stepped up. The high-water mark was reached on 9 December, when 48 sorties were used against Pakistani concentrations. This time round the Manawar Tawi provided a visible forward line of own troops from 7 December onwards.

Punch

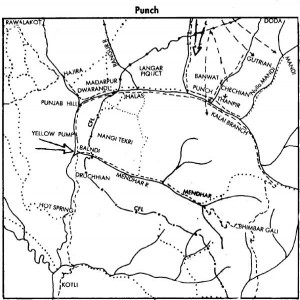

Punch was another objective on which the enemy expended considerable effort: Its defence was the responsibility of 93 Infantry Brigade, commanded by Brigadier (later Major General) M.V. Natu, a formation under 25 Infantry Division commanded by Major General Kundan Singh. The ravines and jungle-clad hills of the region were ideal for infiltration. The CFL ran West of the town of Punch and then swung East to form a bulge in the Kahuta-Haji Pir Pass area (see Fig. 14.2). This bulge, North of Punch, was used by Pakistan in 1965 to infiltrate the Sallaudin force into the Kashmir Valley. She used it again in 1971 in her bid to annex Punch.

Click to buy: Indian Army After Independence

Both sides had strong defensive positions—on the CFL. Kahuta, about 13 kilometres North of Punch as the crow flies, was Pakistan’s administrative base in this area. India had captured the Haji Pir Pass in 1965 and reopened the Uri-Punch road. However, under the Tashkent Agreement, she had returned the pass and the bulge to Pakistan. Thus, Indian ground communications with Punch were only from Rajauri, in the South. Two roads linked these towns: one ran by way of Mendhar and Balnoi while the other went via Thanna Mandi and Surankot. From August onwards, Indian patrols had observed warlike preparations on the Pakistan side, around Kahuta and South of it. This prompted Western Command to reinforce Punch, which was done by inducting 33 Infantry Brigade from 39 Infantry Division of 1 Corps on 25 November.

Major General Akbar Khan, the Commander of Pakistan’s 12 Infantry Division, planned to take Punch with an outflanking move from the East, using two infantry brigades. In a preliminary operation, the Indian defence line North-East of Punch was to be breached by capturing the posts at Danna, Shahpur and Gutrian. Thereafter his two brigades were to infiltrate Southward, reach the Surankot-Punch road and then attack Punch from the South-East, where it was expected to be least defended. Meanwhile, Indian picquets on other parts of the CFL were to be kept engaged by diversionary attacks. The plan was bold in concept but it failed for two reasons. First, Akbar Khan did not take into account the reaction of the Indian garrison, which had defensive positions North and West of his line of advance. Secondly, he made little or no provision for the resupply of his forward troops.

Major General Akbar Khan, the Commander of Pakistan’s 12 Infantry Division, planned to take Punch with an outflanking move from the East, using two infantry brigades. In a preliminary operation, the Indian defence line North-East of Punch was to be breached by capturing the posts at Danna, Shahpur and Gutrian. Thereafter his two brigades were to infiltrate Southward, reach the Surankot-Punch road and then attack Punch from the South-East, where it was expected to be least defended. Meanwhile, Indian picquets on other parts of the CFL were to be kept engaged by diversionary attacks. The plan was bold in concept but it failed for two reasons. First, Akbar Khan did not take into account the reaction of the Indian garrison, which had defensive positions North and West of his line of advance. Secondly, he made little or no provision for the resupply of his forward troops.

Under cover of heavy shelling, which began soon after nightfall on 3 December, the leading battalions of Akbar Khan’s assault brigades moved East and then South, to get to their initial objectives. By 2200 hours the battalion making for Danna had taken an Indian outpost and the second battalion had contacted the picquets at Shahpur and Gutrian. The follow-up battalions advanced soon after, without waiting for the fall of these positions. One of these battalions was required to secure the heights overlooking Mandi, while the other was to make for the Thanpir and Chandak features overlooking the Kalai Bridge on the Surankot-Punch road.

Under cover of heavy shelling, which began soon after nightfall on 3 December, the leading battalions of Akbar Khans assault brigades moved East and then South, to get to their initial objectives.

A detachment of 3 Jammu & Kashmir Militia,5 that had been holding Thanpir, was unfortunately moved out during the early part of the night to reinforce the Shahpur and Gutrian posts before the troops ordered for its relief had arrived. Thus, when the enemy reached Thanpir, it found the post unoccupied, except for some non-combatants. Later, when the relieving troops arrived, the enemy was already in occupation of Thanpir, and they suffered heavy casualties.

From Thanpir, the Pakistanis fanned out and occupied the Nagali and Chandak features. The next morning, they ambushed a BSF patrol near the Kalai Bridge. As a consequence, all traffic on the Surankot-Punch road came to a halt. Unfortunately for the Pakistanis, the radio set of their forward observation officer ceased to function and they could not bring the vehicles halted on the road under artillery fire. The second enemy battalion was also able to reach Mandi, but could do little damage.

Major General Kundan Singh ordered a reserve battalion to move from Jaranwali Gali to Punch during the night of 3/4 December. This battalion was now given the task of clearing Chandak and Thanpir. The Pakistanis at these places were in a tight corner as they had no artillery support and were without food. During the afternoon, those at Chandak began to march back towards Thanpir. The Pakistani troops that had reached Nagali comprised a company of infantry and a platoon from their Special Service Group. They had earlier made their presence felt by opening up on the wagon lines of an artillery unit in the area. A group from 9 (Para) Commando6 soon drove them away after inflicting heavy casualties.

| Editor’s Pick |

By 1000 hours on 5 December, the enemy was withdrawing from Nagali and Chandak and had fallen back on Thanpir. Meanwhile, Indian troops holding Danna had stood their ground despite repeated attacks throughout 4 December and the night of 4/5 December. The enemy suffered heavy casualties, its assault battalion losing its commanding officer. Mines and effective artillery support helped the defenders in a big way.

The attack on Shahpur and Gutrian also failed. These failures on both axes isolated the enemy’s forward troops. At Thanpir, there was utter confusion after the battalion occupying it lost its commanding officer. About 1600 hours on 5 December this battalion withdrew to Kirni, leaving behind large quantities of arms and equipment. The battalion that had reached Mandi also fell back on the night of 5/6 December.

By this time the Pakistani offensive was virtually over. Their troops investing Danna, Gutrian and Shahpur, however, remained in position till 7 December, when they also withdrew. Some elements of their Special Service Group had managed to infiltrate far behind the CFL. They were also mopped up within a few days.

After the failure of their offensive, the Pakistanis became apprehensive of an Indian riposte towards Haji Pir Pass. But the Indian command had no plans for a major counter-offensive in this sector, though the divisional commander did order limited operations along the CFL to improve his defensive posture. In an operation mounted on the night of 10/11 December, some features of tactical importance opposite Madarpur, South-West of Punch, were captured. However, another operation on the night of 13/ 14 December proved a costly failure. It was mounted against Daruchian by 14 Grenadiers and the battalion suffered about 160 casualties, including all the assault company commanders.

By this time the Pakistani offensive was virtually over. Their troops investing Danna, Gutrian and Shahpur, however, remained in position till 7 December”¦

As pan of the attack on Daruchian, Major General Kundan Singh had ordered his para commando group to eliminate six enemy guns which were supponing this position. These 122-mm Chinese-made weapons were located on a ridge near the village of Mandhol. The paratroopers’ operation was a complete success.

Chicken’s Neck

Soon after the Pakistani air-strikes, orders went out for offensive operations to commence within 48 hours. However, the operations which were to support 1 Corps had to be given up or curtailed. As we have seen, 10 Division remained on the defensive after being-pushed out of Chhamb. The deficiency in 1 Corps resulting from the despatch of 33 Brigade to Punch was made good by placing 168 Brigade of 26 Division under 39 Division. This, in turn, led to the cancellation of 26 Division’s advance towards Sialkot and the only important mission this formation undertook was the capture of ‘Chicken’s Neck’.

About 170 square kilometres in area, this narrow strip of Pakistani territory has a small neck in the South, from which a jagged head, with a beak-like point, extends Northwards. The beak points towards Akhnur, with its important bridge over the Chenab. Before Major General Z.C. Bakhshi took over 26 Division, the strip was often referred to as ‘the Dagger’ on account of its shape and the threat it posed to Akhnur. To remove this kind of thinking, he told everyone in his command that the name would thenceforth be Chicken’s Neck and that he was soon going to wring it (it is called Phulkian Salient by the Pakistanis).

Access to the salient from the Pakistani side was over ferries on the Chenab in the South and its defences were generally oriented towards the North and East

The Neck was important to the Pakistanis also. Their Marala Headworks lay South of it and it was a base for infiltration into the Akhnur-Jammu area. Access to the salient from the Pakistani side was over ferries on the Chenab in the South and its defences were generally oriented towards the North and East. Pakistan’s 15 Division was responsible for this area and Indian intelligence had estimated that the Neck was held by about four companies of Chhamb Rangers and a regular battalion, with some tanks in support.

Like his operation against the Haji Pir Pass in 1965, Bakhshi managed to achieve complete surprise in his attack on Chicken’s Neck. His orders to 19 Infantry Brigade, commanded by Brigadier Mohinder Singh, were to infiltrate from the South so as to block the enemy’s route of withdrawal and thus demoralize it before taking its main defences. The brigade was supported by armour and had a group from 9 (Para) Commando under command.

The operation began at last light on 5 December and was successfully completed within 48 hours. However, due to the over-cautious advance of the leading elements and the sandy nature of the terrain. which slowed down the resupply column, the enemy was able to pull out the major portion of its troops from the salient.

After this operation, 26 Division contented itself with small raids on the border outposts opposite its area. The troops released after the completion of the Chicken’s Neck mission remained unused till the cease-fire.

The Shakargarh Bulge

Lieutenant General K.K. Singh, GOC 1 Corps. was Director of Military Operations at Army Headquarters before assuming command of this formation in October 1971. He was, therefore, closely associated with the planning of the operation he was to undertake later. Initially, he set up his Headquarters at Pathankot but moved it to Samba on 2 December. On the morning of 4 December he met Lieutenant General Candeth at Dina Nagar. At this meeting it was decided that the offensive would be mounted on the night of 5/6 December.

Lieutenant General K.K. Singh, GOC 1 Corps. was Director of Military Operations at Army Headquarters before assuming command of this formation in October 1971. He was, therefore, closely associated with the planning of the operation he was to undertake later. Initially, he set up his Headquarters at Pathankot but moved it to Samba on 2 December. On the morning of 4 December he met Lieutenant General Candeth at Dina Nagar. At this meeting it was decided that the offensive would be mounted on the night of 5/6 December.

Before we describe the Corps’ operations it would be worthwhile to take a look at the area in which it operated. The terrain was flat, except for the foothills in the North. The only major river in the area was the Ravi. To its West flowed several minor rivers: Ujh. Tarnah, Bein. Karir, Basantar, Degh Nadi and Aik Nala. Like the Ravi all of them flowed from Indian territory into Pakistan.

Click to buy: Indian Army After Independence

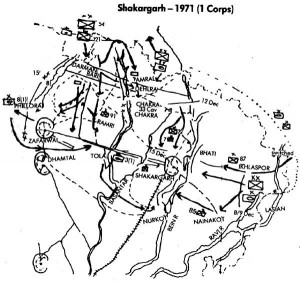

Pakistan’s 1 Corps held the area. From its base at Sialkot, a line of defences ran Eastwards. An anti-tank ditch covered the international boundary up to the Degh Nadi. Thereafter, the Supwal Ditch covered the gap between the Degh Nadi and the Basantar. All major towns had anti-tank ditches, which were integrated into a belt of defences running from the Degh Nadi to Zafarwal, Dhamthal and further down (see Fig. 14.3). Extensive but indifferently laid minefields barred the likely Indian approaches. Communications were fairly good in dry weather.

Besides its three infantry divisions (36, 39 and 54), 1 Corps had two independent armoured brigades (2 and 16), two independent artillery brigades (41 and 31, less a medium regiment), and about two engineer brigade equivalents. The infantry divisions had no integral armour but had their own complement of artillery and engineer elements, besides the ancillary units. The corps had a locating battery and an air OP squadron (less a flight). Headquarters 1 Corps had Number 8 Tactical Air Centre of Indian Air Force affiliated to it.The corps’ battle order looked impressive but its defensive commitments tied it down considerably. The orders to the corps commander were to contain the enemy offensive in his area frontally and then deliver a riposte against enemy lines of communication so as to force it back. In case the enemy did not launch an offensive, K.K. Singh was to advance into the Shakargarh Bulge East of the Degh Nadi and capture the objectives mentioned earlier.

The defensive deployment could at a pinch cover the requirement of a flanking attack on the Pakistanis by anyone of the unengaged armoured brigades.

The initial deployment of the corps was as follows:

- 36 Division – South-East of the Ravi, in the Thakurpur-Gurdaspur-Dina Nagar area.

- 39 Division – North of the Ravi, in the Madhopur-Bamial-Dayalachak area.

- 54 Division – Around Samba, between the Bein River and the Degh Nadi.

The corps’ flanks were covered by 11 Corps in the South and by 15 Corps in the North. However, the former was thin on the ground in the area immeiliately to the South of 1 Corps’ boundary with it and its defences had to be catered for.

Lieutenant General K.K. Singh’s plan required 54 and 39 Divisions to advance South from their bases, while 36 Division was to strike Westward in case the situation warranted. The defensive deployment could at a pinch cover the requirement of a flanking attack on the Pakistanis by anyone of the unengaged armoured brigades. The Pakistani Army remained on the defensive in this sector. But it had considerable offensive potential and the corps commander deployed the following formations for the defence of his area of responsibility:

- 168 Infantry Brigade (26 Division), 323 Infantry Brigade (39 Division) and 16 Cavalry (less a squadron);

- 87 Infantry Brigade (39 Division) and a squadron of 16 cavalry in the Bamial-Parol sector; and,

- 18 Infantry Brigade (36 Division) with a squadron of armour from 14 Independent Armoured Brigade in the Thakurpur-Gurdaspur sector.

Pakistans 1 Corps held the area. From its base at Sialkot, a line of defences ran Eastwards. An anti-tank ditch covered the international boundary up to the Degh Nadi.

Pakistan’s 1 Corps working out of Sialkot area had deployed its integral assets in a defensive role as follows:

- 15 Infantry Division was deployed between the Chenab and the Degh Nadi guarding the Marala-Chapral, Suchetgarh and South-Eastern approaches to Sialkot with an infantry brigade each.

- Initially, 8 Independent Amroured Brigade (four regiments and one armoured infantry battalion) was held centrally in the Chawinda area awaiting the Indian 1 Corps’ offensive pattern to emerge. Once it did it shifted its weight Eastwards to their 1 Corps’ limit of penetration.

- With the Degh Nadi forming the inter divisional boundary, 8 infantry Division was deployed to its East. Its infantry brigades held Zafarwal, Dhamthal, Narowal and Shakargarh in strength converting each into a strongpoint covered by all-round protective minefields and anti-tank ditches. Its fourth brigade (14) was in reserve.

39 Infantry Division

The offensive got off to a good start. Pakistan’s border outposts were cleared during the night of 5/6 December. However, 39 Division got stuck soon after. This division, under Major General B.R Prabhu, was to advance on Shakargarh between the Bein and the Karir Rivers. The divisional commander had none of his own infantry brigades with him. For this operation, he was given 72 Infantry Brigade, with four battalions, from 36 Division. The rest of his order of battle comprised 2 Independent Armoured Brigade (T-55) less a regiment, 1 Dogra (mechanized), a brigade plus in artillery and two regiments plus of engineer resources. Opposing him initially were elements of covering troops from 3 Independent (ad hoc) Armoured Brigade backed up in depth by one infantry brigade.

The division was required to make a two-pronged advance. One column was to advance by way of Dehlra and Chakra and the other by way of Khaira, Harar Khurd and Giddopindi. The leading infantry battalion (3 Sikh LI), supported by a squadron of 7 Cavalry, was to establish a bridgehead at Harar Khurd. In the dark, however, the group lost its way and reached a village about four kilometres North-West of the objective. This did not, by itself, affect the overall plan but the group was thereafter held up at a minefield. When the armour got bogged in the mines, it was pulled back and 3 Sikh LI were told to advance after last light on 6 December.

| Editor’s Pick |

Progress was again slow. The infantry could only get as far as Giddarpur by the morning of 7 December. Around noon that day, the armour reached an unguarded minefield near Parni, across which a bridgehead was established.

Prabhu now ordered 2 Armoured Brigade to break out to the rear of the Harar Kalan-Harar Khurd line. The brigade commander gave the mission to 1 Horse with 1 Dogra (less a company) under command. However, this group soon encountered a second minefield and heavy fire. Without allowing for adequate reconnaissance, the brigade commander launched 1 Dogra and one squadron of armour against Harar Kalan during the night. The attack failed despite heavy casualties of 24 dead and 65 wounded.

At this stage, it was decided to turn this position. During the afternoon of 8 December an outflanking move was begun after breaching a minefield. Unfortunately, after two of the tanks had crossed over, a third blew up on an odd mine. Apprehending attack by tank-hunting parties, the two forward tanks were abandoned. Two trawls, used for the breaching, were also left behind after an attempt to bring them out failed. The brigade commander could have saved the situation by ordering some infantry across the breach but this was not done. The divisional commander too did not intervene. The setback in 39 Division affected 54 Division operating West of the Karir. Dehlra and Chakra, East of this river, had been earmarked as the initial objectives of 39 Division. Its failure to take them exposed the Eastern flank of 54 Division, which had reached a point West of Dehlra on the night of 7 December. The corps commander had, therefore, to order 54 Division to reduce the Dehlra-Chakra position.

Progress was again slow. The infantry could only get as far as Giddarpur by the morning of 7 December.

On 10 December, 72 Brigade attacked Harar Kalan after due preparation and captured it. However, exploitation further South was again held up on a minefield on the other side of the village.

About this time, Lieutenant General K.K. Singh began to have second thoughts about his tasks. There were two reasons for this. First, he realized that 36 Division had a better chance of reaching Shakargarh than 39 Division. Secondly, the situation in the Chhamb-Akhnur sector was aftecting his order of battle To reinforce that sector, the Army Commander had moved a battalion from 168 Infantry Brigade to Akhnur on 10 December and the rest of that brigade had also been placed on a few hours’ notice to move there. At the same time, 54 Division had been ordered to earmark an infantry brigade to replace 168 Brigade in the Ramgarh-Samba area in case the latter moved out. In view of this commitment, further operations by 54 Division would depend on the situation in the Chhamb-Akhnur sector. To launch 36 Division against Shakargarh, the Corps Commander transferred to it most of 39 Division’s combat strength, except for72 Brigade and 7 Cavalry, which he placed under 54 Division. At the same time, he ordered the Headquarters of 39 Division to take over the Ramgarh-Samba area.

54 Infantry Division

As we have seen earlier, the situation in the Chhamb-Akhnur sector had stabilized by 11 December. Thereafter, the battalion sent to this sector from 168 Brigade reverteel to it and 54 Division was freed of the commitment of sending out a brigade.

Major General W.A.G. Pinto, GOC 54 Division, had under him three infantry brigades (47, 74 and 91), 16 Independent Armoured Brigade, under Brigadier A.S. Vaidya (later General A.S. Vaidya, mvc, COAS), less 16 Cavalry, 18 Rajputana Rifles (Mechanized) less two companies, 90 Independent reconnaissance squadron (AMX-13) and two engineer regiments. Of the three divisions under 1 Corps, Pinto had the strongest artillery with four medium regiments. The division’s mission was to capture the Zafarwal-Dhamthal line and then be prepared to go for Deoli and Mirzapur. Facing it were the covering troops of 3 Independent Armoured Brigade, thereafter elements of 24 Infantry Brigade and at the third obstacle 8 Independent Armoured Brigade.

The division’s route of advance lay between the Karir and Basantar Rivers. It came up against the first minefield on 6 December when Pinto ordered 47 Brigade, commanded by Brigadier A.P. Bhardwaj, with 4 Horse under command, to establish a bridgehead across it in the Dudwan Kalan-Bari-Darman area. A calculated risk was taken in trawling the minefield in a dust-haze before last light and, by 1745 hours, a squadron of armour was across and the Bari Line was secured by the evening of 7 December. That night the bridgehead was further enlarged. Dudwan Kalan was captured by 16 Madras with 17 Horse in support, and a company of 18 Rajputana Rifles took Ghamrola by first light.

At this stage, the failure of 39 Division to take the Dehlra-Chakra complex, East of the Karir, began to affect Pinto. On 8 December the enemy brought Dudwan Kalan under fire from across the Karir. The Pakistanis had a strong pivotal position in the Dehlra-Chakra area and unless it was eliminated, 54 Division’s East flank would remain under threat.

Click to buy: Indian Army After Independence

Pinto gave the task to 74 Brigade, led by Brigadier Ujaggar Singh. It had to move all the way back via Bhoi Brahmnan, in the North. After reconnoitring the objective for two successive nights the attack took place on the night of 10/11 December. Chakra was attacked from the rear by 8 Grenadiers and a squadron of 4 Horse. The enemy fought hard and the position fell after a battle lasting over four hours. The enemy lost six M-47/48 Pattons during the action. Dehlra was taken by 6 Kumaon without trouble. The engineers’ contribution to the success of this operation was considerable. Under Major V.R. Chowdhary’s leadership, men of 9 Engineer Regiment cleared a lane through the minefield at Chakra in the face of intense enemy fire.

A few enemy pockets were holding out, particularly in the gap between the positions of the two forward battalions.

Pinto now ordered 91 Brigade, commanded by Brigadier (later Lieutenant General and Army Commander) A. Handoo, to pass through and exploit further South. Handoo expected strong enemy reaction and proceeded with caution. In the event, the brigade met desultory resistance and by 15 December, it was dominating the Shakargarh-Zafarwal road from positions at Ramri, Barwal and Chanda, about a kilometre from that highway.

Preparations for the division’s attack on the Supwal Ditch had begun on 12 December. The operation involved the turning of enemy defences across the Basantar River. Two brigades were to take part. A bridgehead was to be established by 47 Brigade in the Lalial-Sikandarpur-Barapind area, including the South-East shoulder of the Supwal Ditch. The rest of the Supwal Ditch was to be tackled by 74 Brigade in a follow-up operation. The East flank of the enemy defences was covered by a minefield laid in the bed of the river. It was 1,400 metres in depth and the clearing of lanes through it would be a formidable task for the engineers.

The Battle of Basantar

The task of providing a firm base for the operation was given to 91 Brigade and by 1600 hours on 14 December, 3/1 Gorkha Rifles captured Jhumbiyan Manhasan, East of the Basantar, against stiff opposition. The divisional attack was scheduled to go in that night but was postponed for 24 hours for further reconnaissance as very little was known of enemy dispositions or suitable crossing places over the Basantar. However, the postponement brought no advantage. Hardly any information of value was obtained, while the enemy gained time to regroup and reinforce its troops.

After the battle, it came to be known that three infantry battalions of Pakistan’s 24 Brigade were deployed in the Supwal Ditch-Rupo Chak-Jarpal-Barapind area. A company of their divisional reconnaissance and support battalion was on the West bank of the Basantar and a regiment minus of armour supported the brigade. In addition, 8 Independent Armoured Brigade, with at least two regiments of armour and an armoured infantry battalion, was at hand as reserves. A big surprise of the battle was the induction of Pakistan’s 124 Infantry Brigade. It was brought all the way from Rahimyar Khan, South of Multan and used in a fierce counter-attack on 17 December within hours of its arrival. The Pakistan Air Force was quite active in this sector. Having got wind of the coming attack, it put in about 30 sorties against 47 Brigade’s assembly area on 15 December.

In Bangladesh, Pakistani infantry had not shown much inclination to fight at close quarters. Here they were much more tenacious and had to be driven from each position by hand to hand combat.

Besides his three infantry battalions (3 Grenadiers, 6 Madras, 16 Madras), Brigadier Bhardwaj had under him 17 Horse7 and 18 Rajputana Rifles (less two companies). Supporting the operation was the divisional artillery brigade, two medium regiments from 41 Independent Artillery Brigade, the brigaded mortars of 91 Brigade and three field companies. His plan was simple. His leading battalion, 16 Madras, was to capture Saraj Chak and the 5r area. Thereafter, 3 Grenadiers would follow and take Jarpal and Lagwal. There was a considerable gap between the objectives of the two battalions. The third battalion, along with 17 Horse, was to close the gap and expand the bridgehead after first light.

The action began at 2000 hours. Both 16 Madras and 3 Grenadiers met very stiff resistance. In Bangladesh, Pakistani infantry had not shown much inclination to fight at close quarters. Here they were much more tenacious and had to be driven from each position by hand to hand combat. Saraj Chak, Jarpal and Lagwal were captured but the situation remained confused. Bhardwaj, therefore, decided to use 6 Madras to reinforce, rather than expand, the captured positions. A few enemy pockets were holding out, particularly in the gap between the positions of the two forward battalions. The engineers had done their job well and by first light, 17 Horse and 6 Madras arrived into the bridgehead.

The morning mist, common in the Punjab at this time of the year, delayed the forward move of the newly arrived troops. The enemy had the advantage of familiarity with the ground and dawn brought to light a number of machine-gun bunkers in the area not cleared during the night. Some of the enemy infantry had also infiltrated the bridgehead. Enemy artillery and these pockets caused many casualties. Lieutenant Colonel V. Ghai, the commanding officer of 16 Madras, was killed and his second-in-command and adjutant were wounded.

Around 0800 hours on 16 December, a major counter-attack developed from the direction of Lalial and Ghazipur. Two regiments of armour from Pakistan’s 8 Independent Armoured Brigade put in repeated assaults in echelon one at a time. First, 13 Lancers tried their hand. This regiment was decimated. The second regiment was 31 Cavalry which met the same fate. But 17 Horse, under Lieutenant Colonel (later Lieutenant General) Hanut Singh, and the three infantry battalions held the enemy. Good artillery support played its part. The enemy’s fury and desperation can be judged from the fact that by 1600 hours 46 of its tanks had been destroyed.

| Editor’s Pick |

The battle witnessed many acts of valour. The part played by Second Lieutenant Arun Khetarpal of 17 Horse shows the grit and dedication with which officers and men met the challenge. The Indian position at Jarpal was held by two troops from B Squadron of his regiment and 3 Grenadiers. When it came under severe pressure from enemy armour, Khetarpal’s troop and another under Lieutenant Ahlawat were ordered forward from Saraj Chak. While the two troops were advancing under Captain V. Malhotra, the second-in-command of their squadron, they came under attack from recoilless guns concealed in bunkers and groves that lay to a flank. To silence them, Malhotra and Khetarpal made a headlong charge, overran the guns and captured their crew at pistol-point. Then putting them on their tanks, they again moved forward. In the course of this action, the commander of the only other tank left in Khetarpal’s troops was also killed.

Nearing the position occupied by B Squadron, Malhotra saw some enemy tanks withdrawing towards Barapind. Straightaway, he and Khetarpal gave chase. The latter got within range of an M-47 Patton and shot it before the two were ordered to get back to B Squadron’s position.

Soon after, an enemy squadron was seen approaching for attack and a shoot-up ensued. The three tanks under Malhotra were mainly responsible for taking on the enemy and completely breaking up the assault. Ten Pakistani tanks were destroyed in quick succession. Of these, Khetarpal had accounted for four. During the engagement, Ahlawat’s tank was hit. He was wounded and had to be evacuated. Malhotra’s own gun jammed. This left Khetarpal facing the oncoming enemy alone. His tank was hit soon after whereupon it burst into flames and he was severely wounded. Seeing this, Malhotra ordered him to abandon his tank. Khetarpal, however, saw that the enemy was still pressing the attack and there was nothing to stop it from breaking through. So he decided to fight on and told Malhotra: “No, Sir, my gun is still functioning and I’ll get these bums”. Thereafter he kept engaging the enemy from his burning tank and destroyed a tank that was less than a hundred metres from him. That tank carried the commander of the Pakistani squadron, who, in turn, scored a hit on Khetarpal’s tank. This resulted in this brave and fearless officer’s death. Khetarpal’s citation later said: “His calculated and deliberate decision to fight from his burning tank was an act of valour and self-sacrifice beyond the call of duty”.The country paid a tribute to Arun Khetarpal with a posthumous award of the PVR.

Pakistan’s 13 Cavalry had mounted this counter-attack. Major Nisar, the squadron commander who led the charge, had abandoned his tank after it had been shot up by Khetarpal. He was so impressed by the gallantry of the three tank commanders who had broken up his assault that he came across to meet them after the cease-fire. He could, however, only meet one of them, Captain Malhotra.

The night of 16/17 December was relatively quiet. It was, however, to be the calm before another storm. Just before dawn, the second and third major counter-attacks developed. Massive artillery shelling preceded infantry assaults in brigade strength. Two battalions of the enemy’s recently arrived 124 Brigade attacked vigorously from the direction of Barapind but were thrown back. This was made possible by the determination of the jawans to hold on to what they had taken and the excellent artillery support they received. 3 Grenadiers’ success in repulsing the enemy owed much to Major Hoshiar Singh’s gallantry and his conduct is sure to inspire future generations of officers of the Indian Army.Hoshiar Singh was in command of the left forward company of his battalion. He had led it in the storming of Jarpal. During the enemy’s counter-attack on 16 December, he went from trench to trench to cheer his men, disregarding the bullets that flew around him. When the Pakistanis counter-attacked on the morning of 17 December his company faced an assault by one battalion (39 Frontier Force). He was seriously wounded by a shell-splinter in the bombardment that preceded the attack.

Click to buy: Indian Army After Independence

Despite his wound and in utter disregard of his own safety, he again moved about in the open from position to position to encourage his men. When a shell landed near one of his machine-gun posts, injuring its crew, he manned the gun himself and accounted for a good number of the enemy. After the battle, 85 enemy dead were counted on the company’s front, including the commanding officer of the enemy battalion and three other officers. Even after the attack was repulsed, Hoshiar Singh refused to be evacuated till the cease-fire was declared. His superb leadership and dauntless courage brought him the PVR. He was the third man in the history of the Indian Army to live to receive this award.

Due to lack of intelligence on the Pakistani defensive layout and their tactics, 1 Corps commenced operations in an area which was very heavily defended by minefields.

About 1000 hours the enemy laid a smoke-screen covering the whole front, obviously in preparation for launching another attack. Defensive artillery fire was therefore, continued and the attack, if any, fizzled out. That day, 4 Horse (less a squadron) moved into the bridgehead. Thereafter the enemy’s chances of success withered away. With the cease-fire coming into effect during the evening, the Indian advance also came to a halt, seven kilometres short of Zafarwal.

36 Infantry Division

Turning to 36 Division, we find that this formation was on a watching brief till 8 December. Under Major General B.S. Ahluwalia, it had till that day only two infantry brigades – 18 and 115 – and a regiment of armour.115 Infantry Brigade had only two battalions (4 Grenadiers and 10 Guards), 1 Mahar having been placed under 39 Division earlier. However, the reorganization of 12 December gave Ahluwalia 87 Brigade, till then marking time in the Bamial-Parol area. The Mahars also returned to 115 Brigade. In the shape of armour, 36 Division now had the Headquarters of 2 Independent Armoured Brigade, 1 Horse, 14 Horse and one squadron from 64 Cavalry (of 14 Independent Armoured Brigade). Its artillery comprised two medium regiments, two field regiments, one heavy mortar battery and one air defence battery. Three engineer regiments and 1 Dogra Mechanized (less a company) completed its order of battle in so far as fighting elements were concerned.

A spring-board for launching the division was secured early enough. On the night of 5/6 December, 18 Brigade, under Brigadier (later Major General) Prithvi Raj, secured the Lasian Enclave East of the Ravi thus obtaining a good crossing over the river. This action would not have gone unnoticed by the Pakistanis and it certainly helped to divide their attention to the area East of the Bein River. However, it was only after the advance of 39 Division was checked that the corps commander ordered Ahluwalia to advance towards Shakargarh by way of Nurkot. Ahluwalia gave the task to 115 Brigade, commanded by Brigadier (later Lieutenant General) H. Kaul. A battalion from 18 Brigade and 14 Horse were placed under Kaul for the operation.

Surprisingly, the operation was mounted that very night by 115 Brigade. The results were disastrous.

The advance began on the night of 8/9 December. By next morning the Engineers had a Class 9 bridge ready over the Ravi. Nainakot, the first likely enemy position in the brigade’s path, was occupied without opposition around noon on 10 December: the enemy had vacated it earlier. During the advance, 14 Horse encountered a squadron of Pakistan’s 33 Cavalry (M-47/48 Pattons) on 11 December and put in a brisk action, destroying eight enemy tanks for no loss of theirs. By noon on 12 December, the East bank of the Bein was secured. It was only thereafter that things started going wrong.

On 12 December, Candeth visited this sector and met the corps commander. After the meeting, the latter outlined his plan for the capture of Shakargarh. By this time, 87 Brigade had advanced from its base and crossed the Ujh and Tarnah Rivers. Its orders were to make for Shakargarh by way of Ikhlaspur. In doing so, it would not only protect 36 Division’s Northern flank, but also pose a convergent threat to Shakargarh while 115 Brigade advanced for the kill from the East. Another move to help the capture of the objective would be a simultaneous advance towards it by 72 Brigade. The Southern flank of 115 Brigade was to be covered by 2 Independent Armoured Brigade. The corps commander made it very clear that the attack on Shakargarh would only be put in after due preparation. Ahluwalia assured him that it would be feasible to go in on the night of 13/14 December. The next day in the evening, he rang up the corps commander and asked for a postponement for 24 hours saying preparations were not yet complete. The corps commander agreed.

Surprisingly, the operation was mounted that very night by 115 Brigade. The results were disastrous. A company of 4 Grenadiers was sent across the Bein with the aim of securing a foothold West of the river. No reconnaissance appears to have been carried out as the troops were unaware of the minefield covering Shakargarh from the East. After this company had crossed over, the rest of the battalion and a squadron of 14 Horse were ordered to build up on it. Meanwhile, the enemy encircled the company on the West bank and the tanks ran into a minefield while trying to cross over. The infantry and the armour then came under intense fire and were ordered back. Besides other casualties, the Grenadiers lost 72 all ranks as prisoners. On the Northern axis, 87 Brigade made good progress. By the morning of 14 December it had captured two villages, Bhatti and Shahpur Chinjore, on the East bank of the Bein.

The corps commander went to 36 Division that morning to see things for himself. He could get no satisfactory explanation for the previous night’s happenings. Ahluwalia now told him of his plan for another assault that night (14/15 December). The corps commander could see for himself that preparations, such as artillery fire tasks and Engineers’ co-ordination, were not yet complete. But he did not postpone the operation as Ahluwalia was confident of success.

The second assault ended in a fiasco. For unknown reasons, 4 Grenadiers, who had received a severe mauling the previous night, were again given the leading role.

The second assault ended in a fiasco. For unknown reasons, 4 Grenadiers, who had received a severe mauling the previous night, were again given the leading role. Enemy guns opened up while they were in the forming-up place. One of the companies was caught in the open and, although the casualties were not many, some of the sub-units got scattered and the attack had to be called off.

On the Eastern approach, 3/9 Gorkha Rifles, the leading battalion of 87 Brigade, put in a spirited attack. A village on the outskirts of Shakargarh was its objective. The battalion struggled valiantly on the wrong side of the minefield until orders were given to the assault companies to withdraw. The mine-breaching operation had let down the Gorkhas. It could not begin on time and the breach, when made, was not successful. The battalion suffered heavily and some of its men were taken prisoner.

The second attack having fizzled out, the corps commander now decided to bring up 18 Brigade and put in a third attempt on the night of 17/18 December. Preparations commenced straightaway but the timing coincided with the cease-fire, and it had to be abandoned. The advance of 72 Brigade also did not make much headway as the armour was obstructed by minefields.

| Editor’s Pick |

Thus ended 1 Corps’ offensive without the capture of its initial objectives. All it had achieved in doing was to drive the enemy’s covering troops to its main defended positions. During 12 days it had advanced about 13 kilometres. The lack of spectacular results was mainly due to the dispersal of resources. Four infantry brigades were tied up in base areas and the multi-pronged approach precluded the concentration of adequate strength for a decisive breakthrough. Of the two armoured brigades with the corps, not more than one regiment was in contact with the enemy at any point of time.

The complete command structure of 1 Corps was smitten with indecision. A constant narrowing down of objectives – from Ravi-Marala Link Canal to Zafarwal-Dhamthal to Zafarwal and Shakargarh – took place giving the Pakistanis enough time to discern major thrusts and therefore objectives. GOC 1 Corps, by subordinating his two armoured brigades to his infantry division commanders, surrendered all mobile assets. In the event, neither were these formations successful nor did he have the infantry divisions to crack open the series of obstacles by combined action. The six long-range medium regiments were also unable to suppress Pakistani artillery which took a heavy toll.

Due to lack of intelligence on the Pakistani defensive layout and their tactics, 1 Corps commenced operations in an area which was very heavily defended by minefields. GOC 1 Corps and his formation commanders walked into this sector blindfolded and made no attempts to break free of its shackles by concerted, orchestrated offensive action.

Due to lack of intelligence on the Pakistani defensive layout and their tactics, 1 Corps commenced operations in an area which was very heavily defended by minefields. GOC 1 Corps and his formation commanders walked into this sector blindfolded and made no attempts to break free of its shackles by concerted, orchestrated offensive action.