The decision to make Se La the main defensive position of 4 Division and to put half its fighting strength there had been unwise. However, a withdrawal from that position when it was under a frontal attack and had been outflanked could bring nothing but disaster. In his battles against the Japanese, Slim had evolved a standard tactic for such a situation.

When any force was cut off, it would stand and not withdraw; at the same time, it would try to cut the enemy’s lines of communication. Air supply was assured to the besieged force and other troops were sent to relieve it. With some effort, Se La could have been maintained by air.

Click to buy: Indian Army After Independence

The morale of the men there was by no means cracking; the Garhwalis had shown that. What was missing was determined and foresighted leadership. A determined stand at Se La might have proved a turning point in the Kameng battle.

The Chinese closely followed the Sikh LI as the latter withdrew and opened up with mortars and small-arms. It would appear that the information regarding the Sikh LIs withdrawal did not reach the men of 1 Sikh”¦

Kaul returned to his Headquarters around 1930 hours. Within 15 minutes Pathania was again on the line to seek permission for abandoning Se La. Kaul did not agree and told Pathania that Se La had a week’s supplies and should be able to hold out even if cut off.

Later during the night, while Kaul and his guests from Delhi and Lucknow were at dinner, the telephone rang again; it was Pathania reiterating his request for a withdrawal. Kaul told him that he must hold on at Se La that night and that he would give final orders the next morning. However, after consultation with Thapar and Sen, he later sent Pathania a directive. Instead of being a firm and precise command, it left room for different interpretations. Among other things, the directive told Pathania: “You will hold on to your present position to the best of your ability; when any position becomes untenable I delegate the authority to you to withdraw to any alternative position you can hold”.25 By the time the directive was ready, communications between 4 Division and 4 Corps Headquarters had broken down. It reached Pathania via 48 Brigade in the early hours of 18 November. By then much had happened at Se La.

Around 1830 hours on 17 November, Hoshiar Singh held a conference, at which a plan for withdrawal on the night of 18/19 November was chalked out and conveyed to those who could not attend. He made it clear that the information was for them personally and that he would brief them in detail the next morning.

Later that night around 2200 hours, Hoshiar Singh rang up his brigade major from his bunker to tell him that he had ordered 2 Sikh LI to withdraw during the night from its position on Kya La, North of Se La; the battalion was to leave one company covering the road to Se La. He had done this, he told the brigade major, as there were reports of enemy build-up for a dawn-attack against Kya La and he did not want the battalion to be involved in battle. Hoshiar Singh had informed Pathania of this decision, as also the commanding officer of 1 Sikh, through whose positions 2 Sikh LI would withdraw. But the move, when it began, resulted in chaos.

Brigadier Hoshiar Singh reached Phutang after some days but his small party was later ambushed by the Chinese and he was killed.

The Chinese closely followed the Sikh LI as the latter withdrew and opened up with mortars and small-arms. It would appear that the information regarding the Sikh LI’s withdrawal did not reach the men of 1 Sikh; the firing and unexpected movement of 2 Sikh LI caused panic among them and they abandoned their positions. By then, communications between Brigade Headquarters and battalions had broken down, adding to the confusion.

Around 0400 hours on 18 November, Hoshiar Singh went up to Se La to see things for himself and found 2 Sikh LI mixed up and completely disorganized. He tried to restore order. An hour or so later, when he returned to his Headquarters, he discovered that his line and radio communications with Divisional Headquarters had also broken down. He now decided to withdraw straightaway to Senge as one side of Se La was already in enemy hands. He tried to inform everyone who could be contacted. He could not get in touch with 4 Sikh LI, on the left shoulder of Se La and the unit was left to its fate.

The head of the brigade column reached the vicinity of Senge around 0900 hours. Here Hoshiar Singh decided to send the vehicles straightaway to Dirang Dzong. His brigade major had informed 48 Brigade and 4 Corps from a wayside camp that the brigade was making for Bomdi La by way of Dirang Dzong. Neither he nor Hoshiar Singh was aware that Dirang Dzong was being evacuated even as 62 Brigade was making for the place.

| Editor’s Pick |

Of the infantry that had accompanied Hoshiar Singh from Se La, only the Garhwalis were in good shape; 2 Sikh LI and 1 Sikh were still sorting themselves out. There was the risk of hot pursuit by the enemy. He, therefore, decided to push off to Dirang Dzong with the Garhwalis as his advanced guard; 2 Sikh LI and l Sikh were to follow; 13 Dogra (less two companies with Divisional Headquarters) was to act as the rearguard.

The advanced guard was divided into two groups. Two of the companies under Lieutenant Colonel Bhattacharjea moved along the heights; the remainder of the battalion was under the brigade commander, leading the main column. The move had begun at about 1040 hours. When the main column rounded a bend in the road beyond the village of Nyukmadong,

“a harrowing sight suddenly came into view. Vehicles, guns and bulldozers lay scattered. The road and the shallow drain running along it were littered with the bodies of the dead and the dying. This was the end of the vehicle column”.26

The main foot column was on the move till 1400 hours when it came under heavy fire from the heights overlooking the road. Soon, the Chinese appeared at the rear also. Efforts to dislodge the enemy failed and by 1600 hours the column was completely disorganized. As darkness enveloped the scene, control was lost and the column disintegrated into small parties. Brigadier Hoshiar Singh reached Phutang after some days but his small party was later ambushed by the Chinese and he was killed.27

After the conference, when Pathania went in his jeep to watch the progress of road-clearance, he witnessed utter confusion.

The Garhwalis under Bhattacharjea cleared the enemy from several places along their route of withdrawal. However, beyond Nyukmadong this group lost touch with the main column. On arrival at Dirang Dzong after midnight, it was ambushed. Most of its men became casualties; Bhattacharjea was taken prisoner with some others. When a count was later taken, 34 officers, 43 JCOs and 1,610 other ranks of 62 Brigade were found missing. The Garhwalis won many awards for gallantry, including two MVCs and seven Vir Chakras.

Major General Pathania abandoned Dirang Dzong in the forenoon of 18 November. Lying in a valley, the Headquarters of 4 Division was hardly capable of defence. Early that morning he had sent off the three infantry companies with him to bar the enemy’s route to Bomdi La. Later he called a conference. ‘All contact with 48 and 62 Brigades had by then been lost and the atmosphere was one of impending doom’. While the situation was being discussed, an officer of 19 Maratha LI came at the double to Divisional Headquarters with the news that the Chinese had arrived at Munna Camp on the Bomdi La road, only a few kilometres from Dirang Dzong.

This was enough ground for the GOC to decide that Dirang Dzong be abandoned. He told his audience that his intention was to withdraw to Bomdi La by way of Manda La. This pass lay South-West of Bomdi La and a track leading to it ran due South from Dirang Dzong. No plan for the withdrawal was given out. The last order that Pathania gave was that the two companies of Dogras, already deployed East of Dirang Dzong and the tanks of 7 Light Cavalry should clear the road-block which the enemy had just established. He told the squadron commander of 7 Light Cavalry that if he could not fight through to Bomdi La, he should abandon the tanks and withdraw with his men to the plains.

After the conference, when Pathania went in his jeep to watch the progress of road-clearance, he witnessed utter confusion. The tanks had advanced from their harbour but South of Dirang Dzong the road was completely choked with abandoned vehicles. The tanks could go no further. Soon after, the Chinese attacked this jumbled confusion of men and vehicles from the heights along the road. Without more ado, Pathania and his staff left their vehicles and took the Manda La track. On the way, he learnt that Bomdi La had fallen and made for Phutang. Kaul picked him up in his helicopter two days after the cease-fire.After Pathania’s departure from Dirang Dzong, some officers of the rank of major and below tried to rally the troops into a scratch force to fight their way into Bomdi La. However, in the face of Chinese pressure, their efforts soon fizzled out. Units split into small parties and made for the plains.

After the conference, when Pathania went in his jeep to watch the progress of road-clearance, he witnessed utter confusion. The tanks had advanced from their harbour but South of Dirang Dzong the road was completely choked with abandoned vehicles. The tanks could go no further. Soon after, the Chinese attacked this jumbled confusion of men and vehicles from the heights along the road. Without more ado, Pathania and his staff left their vehicles and took the Manda La track. On the way, he learnt that Bomdi La had fallen and made for Phutang. Kaul picked him up in his helicopter two days after the cease-fire.After Pathania’s departure from Dirang Dzong, some officers of the rank of major and below tried to rally the troops into a scratch force to fight their way into Bomdi La. However, in the face of Chinese pressure, their efforts soon fizzled out. Units split into small parties and made for the plains.

Among those who had attended Pathania’s conference was the commander of 65 Brigade. When the conference ended, he went to his Headquarters and after informing his staff of the withdrawal order, drove away in his jeep. One of his battalions, 19 Maratha LI, took the Manda La track soon after and reached Phutang before the Chinese got there. The brigade’s second battalion, 4 Rajput, could not withdraw as one body as its companies were widely dispersed. The Rajputs had been in contact with the enemy since 14 November and had fought a company-action North of Nyukmadong on 16 November, losing many men. Two of their companies withdrew independently.

The Rajputs had been in contact with the enemy since 14 November and had fought a company-action North of Nyukmadong on 16 November, losing many men.

The rest, under Lieutenant Colonel B.N. Avasthy, began to withdraw on 19 November. Four days later, the Chinese ambushed them South-West of Bomdi La. They fought gallantly against superior numbers and suffered heavy casualties. Among the killed was the battalion commander. A count after the withdrawal showed that 37 of the battalion had been killed, while 226 were missing.

In a radio signal to Eastern Command and Army Headquarters, sent around 1730 hours on 18 November, Kaul informed his superiors: “I am just going to the Bomdi La battle”. Unfortunately for him, the Chinese were always a few steps ahead of him. An hour before he had put his signature to that message, Brigadier Gurbux Singh had ordered a withdrawal from Bomdi La. Kaul did not know at the time that Dirang Dzong had fallen. He had been out of touch with 4 Division since 0730 hours that morning. But he knew that prospects were bleak and reflected it in his signal by repeating his request that the Government should seek the help of foreign armies and air forces to throw back the advancing Chinese.

Among the last-minute attempts to reinforce 4 Division was the move of 67 Infantry Brigade from Nagaland. Its Headquarters and advance parties from units reached Misamari on 14 November. Two days later, its commander, Brigadier M.S. Chatterjee, left for Dirang Dzong to meet Pathania. He arrived there on the morning of 17 November, only to witness the rout the next day.

One of the battalions of 67 Brigade was flown to the Lohit sector. The advance parties of Brigade Headquarters and one of the remaining battalions – 3 Jammu & Kashmir Rifles — reached Bomdi La around 0930 hours on 18 November. Brigadier Gurbux Singh ordered the men from Jammu & Kashmir Rifles to take up a position West of Bomdi La, where 5 Guards had earlier been deployed.

The artillery could not take on the enemy as communications between the guns and the forward observation officer had broken down.

Bomdi La was poorly held. North of the town was 1 Sikh LI, less its company at Phutang. The defences East of the town were held by 1 Madras. Brigade Headquarters was South of the Deputy Commissioner’s bungalow. The units had no wire or mines to strengthen their defences and they only had their first-line scale of ammunition. This was to some extent due to the fact that Se La had been getting preference for stores and equipment. The Headquarters of 67 Brigade was placed under 48 Brigade on arrival.

Shortly after the arrival of the advance elements of the new brigade at Bomdi La, Kaul ordered 48 Brigade to send out a mobile column to Dirang Dzong. Gurbux Singh protested but was overruled and told to despatch the column within 45 minutes. Sent around 1100 hours, the column consisted of two tanks of 7 Cavalry, a section of mountain guns and two companies of 1 Sikh LI. Only sentries and cooks were left in the positions which the two companies had been holding, except for a section of medium machine guns that remained behind.

The Chinese attacked an hour after the column left. Though their positions were denuded, the Sikh LI repulsed the enemy. Gurbux Singh now ordered the advance party of 3 Jammu & Kashmir Rifles and a platoon of 377 Field Company to fill the gap left by the companies that had been pulled out. At the same time, he recalled the mobile column and ordered that the two companies of 1 Sikh LI should re-occupy their old defences. Around 1330 hours the battalion beat back another assault with support from artillery and medium machine guns. However, an hour or so later, while its two companies were re-occupying their positions, the Chinese struck again and overran most of the battalion’s positions. Attempts to retrieve the situation failed.

Meanwhile, 48 Brigade Headquarters and the gun positions had come under small-arms fire; only the field guns and the tanks were holding the enemy at bay. Around 1630 hours, the brigade commander ordered a withdrawal to Rupa, 14 kilometres South of Bomdi La. Unfortunately, the withdrawal order did not reach every unit. One of the units that did not get it was 1 Madras. At about the time Gurbux Singh issued that order, the Chinese were forming up to attack this battalion. The artillery could not take on the enemy as communications between the guns and the forward observation officer had broken down. Soon after, when the Chinese put in an attack, they succeeded in taking a part of the battalion’s position. The battalion commander had sent out a patrol a short while earlier to establish contact with Brigade Headquarters as he had been out of communication with it. The patrol returned with the information that there was no one at the place where the Headquarters had been.

| Editor’s Pick |

Left to himself, the battalion commander withdrew his unit in the night and made for Tenga Valley. He presumed that the rest of the brigade too would have gone there. However, in following the jungle tracks, the battalion lost its way, and was ambushed on 21 November. Small parties reached Charduar later. A count showed that the battalion had 245 of its personnel missing including the battalion commander.

Brigadier Gurbux Singh’s hurried departure from Bomdi La created a great deal of confusion. While his party was on its way to Rupa, the main body of 3 Jammu & Kashmir Rilles was making for Bomdi La by a different route. The battalion arrived there around 0500 hours on 19 October and found that the Chinese had not yet occupied the place. The battalion commander, Lieutenant Colonel Gurdial Singh, decided to stay put and occupied a defensive perimeter around the dropping zone.

Units were hurriedly told what defensive positions to occupy but before they could even move into them, the Chinese had opened up.

About this time, another battalion of 67 Brigade was making for Bomdi La. This was 6/8 Gorkha Rifles. When the convoy carrying this battalion reached Tenga towards the evening, the road was choked with refugees and an unending stream of Army vehicles coming from the direction of Bomdi La. As it was impossible to make further progress, the battalion commander, Lieutenant Colonel G.S. Kale, halted the convoy and as a temporary measure, ordered his unit to occupy the high ground dominating the Tenga Valley camp. He made arrangements to stop the stragglers and then set out to meet Brigadier Gurbux Singh. The meeting took place at Rupa and Kale was told to take his battalion to Bomdi La.

Evidently, Gurbux Singh was having second thoughts about Bomdi La. He had earlier sent his brigade major to Tenga to get in touch with 4 Corps and report the situation. The brigade major spoke to the GSO 1 at Corps Headquarters on the telephone around 2130 hours and was told that the Brigade, should withdraw to Foot Hills. However, when this officer got back to Rupa, he found that Gurbux Singh had meanwhile left for Bomdi La. He caught up with him around 0200 hours (19 November).

On arrival at Bomdi La, Gurbux Singh met the commanding officers of 3 Jammu & Kashmir Rifles and 22 Mountain Regiment. Manning the defences around the dropping zone were the 3 Jammu & Kashmir Rifles, a field battery, two tanks of 7 Light Cavalry and a few men of 1 Sikh LI. After taking stock of the situation, Gurbux Singh ordered all troops at Bomdi La to withdraw before first light. The convoy of 6/8 Gorkha Rifles was only a few kilometres from Bomdi La when it was ordered to countermarch.

To add to the prevailing confusion, 4 Corps reversed its earlier orders and told 48 Brigade to hold Rupa. This happened at 0630 hours. Units were hurriedly told what defensive positions to occupy but before they could even move into them, the Chinese had opened up. They were already holding the heights. The brigade now fell back upon Tenga, with 6/8 Gorkhas and two tanks of 7 Light Cavalry acting as the rearguard.

At Tenga, Gurbux Singh received orders to pull back to Chaku. By 1730 hours, the remnants of 48 Brigade had reached Chaku. A defensive position was then organized to cover the approach from Rupa.“In the absence of tools, the men had to use bayonets and mess-tins to dig trenches. The digging continued till about 0230 hours (20 November) when the Chinese attacked from three directions. By this time most of the troops were extremely demoralized and hardly any command or control existed. It was a very dark night and after some fighting, the units broke up into small parties and made for Foot Hills”.28

At Tenga, Gurbux Singh received orders to pull back to Chaku. By 1730 hours, the remnants of 48 Brigade had reached Chaku. A defensive position was then organized to cover the approach from Rupa.“In the absence of tools, the men had to use bayonets and mess-tins to dig trenches. The digging continued till about 0230 hours (20 November) when the Chinese attacked from three directions. By this time most of the troops were extremely demoralized and hardly any command or control existed. It was a very dark night and after some fighting, the units broke up into small parties and made for Foot Hills”.28

During the withdrawal, the 3 Jammu & Kashmir Rifles fought an action in the Tenga Valley and suffered heavy casualties, with 98 of their personnel missing (including the commanding officer). The number of missing in 6/8 Gorkha Rifles was 147. 1 Sikh LI had only 16 missing; their remaining casualties were 22 killed and 35 wounded.

The announcement of cease-fire was as sudden as the invasion had been. In fact, Indian newspapers published the news before members of the Cabinet knew of it.

The curtain came down just before midnight on 20 November when the Chinese announced a unilateral cease-fire, effective from the midnight of 21/22 November. The announcement said that the Chinese force would begin to pull out on 1 December and would withdraw to positions ‘20 kilometres behind the line of actual control(LAC) that existed between the two countries on 7 November 1959’.

The announcement of cease-fire was as sudden as the invasion had been. In fact, Indian newspapers published the news before members of the Cabinet knew of it. On the morning of 21 November, Lal Bahadur Shastri, the Home Minister, was at Delhi airport to take a plane for Tezpur. He was going there to study the situation. Seeing an excited crowd at the news-stand, a member of his party went and bought a newspaper which gave the announcement of the cease-fire. Shastri immediately drove to Nehru’s residence with the news.

According to some sources, Chou En-lai had called the Indian charge d’ affaires at Peking to his residence the night before the announcement was made and told him in detail of China’s intentions. Delays in enciphering and deciphering the message and in its transmission, were responsible for the embarrassing situation.

The Chinese did not follow Indian troops beyond Chaku, though they did send some patrols and there were stray clashes after the cease-fire. In the civil area of Tezpur, there was great panic in the wake of Indian reverses. The civil administration broke down completely, with senior officials deserting their posts. On 20 November, the main Headquarters of 4 Corps was ordered to move to Gauhati by train. However, the train staff fled and the Headquarters left by road on 21 November. When the news of the cease-fire reached Tezpur, the road-convoy was recalled.

The civil administration broke down completely, with senior officials deserting their posts.

On 19 November, 5 Infantry Division had begun to arrive at Foot Hills from Punjab. But it was, by then, too late to retrieve the situation. Had this division arrived a week earlier, or had General Pathania held on to Se La till its arrival, the story in Kameng might have been different. The delay in pulling out 5 Division from Punjab was due to the fact that India was not sure of Pakistan’s intentions during the early stages of the hostilities.

THE REST OF NEFA

The terrain in the Lohit sector is no different from the rest of NEFA. The Mishmis form the dominant tribal group of the region. The main defended sector was Walong. This village, situated about 32 kilometres from the McMahon Line, lies in a bowl surrounded by high hills. The Lohit River, on whose banks the village lies, is a tributary of the Brahmaputra.

| Editor’s Pick |

The route to Tibet mostly follows the Lohit. In 1962, Teju was the road-head; the railhead was at Talap, 48 kilometres further back on the South bank of the Lohit. Due to its extremely strong current, the Lohit is neither navigable nor fordable. The Mishmis had put up some rope-bridges but these were shaky and took time to negotiate. The Chinese brought rubber dinghies for crossing the Lohit. Walong had an air-strip but it was so small that it could only take Otters and Caribous. These planes were the only means of supply to this sector, besides air-drops.

As part of the ‘forward policy’, the Assam Rifles had set up a post on 30 June 1962 on a feature called Mohan Ridge, which runs from the East bank of the Lohit towards the border trijunction between India, Tibet and Burma. Here the Lohit flows in from Tibet at a height of 1,300 metres only even though the McMahon Line on either side varies in height from 2,500 to 3,500 metres.

Chinas hostile intent became evident on 18 October when it was discovered that a detachment of Chinese troops, led by a lama, had occupied a hill (Point 10,070) South of the McMahon Line.

The Chinese had a post facing Mohan Ridge at Sama, a Tibetan village about five kilometres from the border. A little further back, at Rima, was the Chinese forward base. As we have mentioned elsewhere, 5 Brigade originally was responsible for all sectors of NEFA barring the Kameng Division.

Evidence of Chinese activity in this sector came in the beginning of August, when their patrols could be seen across the border. Later, when a heavy build-up of Chinese posts was reponed, a company of 6 Kumaon was moved forward to Dichu, a Mishmi village South of Mohan Ridge, separated by a stream of the same name. This battalion had arrived in Walong in March 1962. In the first week of October, 4 Sikh arrived in the sector.

China’s hostile intent became evident on 18 October when it was discovered that a detachment of Chinese troops, led by a lama, had occupied a hill (Point 10,070) South of the McMahon Line. To check further intrusions, an Assam Rifles’ platoon was deployed on a feature facing this hill. At the same time, a platoon of the Kumaonis was moved to Mohan Ridge.

On the night of 20/21 October, Indian observation posts saw numerous lights moving in and around Sama. On the following day, the Chinese were seen digging in their area and clearing paths for mules through the jungle towards Mohan Ridge. All this activity portended an attack and the Indian defended locality at Mohan Ridge was reinforced with another Kumaoni platoon.

The attack came a few minutes after midnight. The Kumaonis stuck to their positions, their mortars taking a heavy toll of the enemy. Around 0300 hours the fighting ceased. ‘The silence all round gave the impression that the Chinese had withdrawn. But they hadn’t. Under cover of the dark, they silently infiltrated on the flanks and the rear of the Indian positions. At first light they attacked again’. The fighting now became intense. However, as it was not possible to reinforce Mohan Ridge, the troops there and at Dichu were ordered to fall back on Kibithu, a village lying three kilometres South of the McMahon Line.The intermixing of companies made little sense to anyone, especially the fighting troops. No commander made the necessary readjustments both to the defensive layout as well as to the command and control set-up. The brigades’ dispositions were essentially linear with no depth.

The attack came a few minutes after midnight. The Kumaonis stuck to their positions, their mortars taking a heavy toll of the enemy. Around 0300 hours the fighting ceased. ‘The silence all round gave the impression that the Chinese had withdrawn. But they hadn’t. Under cover of the dark, they silently infiltrated on the flanks and the rear of the Indian positions. At first light they attacked again’. The fighting now became intense. However, as it was not possible to reinforce Mohan Ridge, the troops there and at Dichu were ordered to fall back on Kibithu, a village lying three kilometres South of the McMahon Line.The intermixing of companies made little sense to anyone, especially the fighting troops. No commander made the necessary readjustments both to the defensive layout as well as to the command and control set-up. The brigades’ dispositions were essentially linear with no depth.

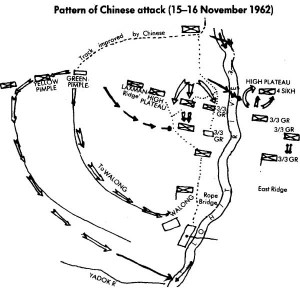

The Chinese held two features, Green Pimple and Yellow Pimple, facing the Kumaonis’ forward locality in the far West. During the lull, they had built a track to these positions under cover of the intermittent shelling that marked the period. From observation posts on these hills, they were able to bring down accurate fire on Indian defences from their mortars and artillery. To deprive the enemy of this advantage, Rawlley ordered 6 Kumaon to capture Green Pimple. However, the Kumaonis’ assault, put in on 6 November, did not succeed.

The Chinese had attacked the Ladders on the morning of 15 November, but suffered heavily in a frontal assault.

The Pimples’ area was obviously the base for the Chinese attack by infiltration on the Western flank. Rawlley, therefore, ordered another attack, again on Green Pimple. Again the task was given to the Kumaonis, with the Sikhs making a diversionary manoeuvre. The attack went in on 14 November. Despite heavy opposition, the Kumaonis were able to reach within 50 metres of their objective. However, the enemy held them there; he had bunkers near the top of the hill. Around 1700 hours, Rawlley ordered the battalion to stand firm in its positions.

Shortly before midnight, the enemy counter-attacked. The Kumaonis’ assault companies were encircled and they could break out only after bitter fighting. The remnants reorganized at a feature called Trijunction, which had been the base for this operation. This position also came under attack soon after but the Kumaonis held their ground. On the morning of 15 November, the Chinese attacked Trijunction a second time but were again repulsed.

The previous day, 4 Dogra had begun to arrive at Walong. A company of this battalion and the men collected from other Kumaoni localities (which the Dogras had taken over) were rushed to Trijunction on the night of 15/16 November. Thus reinforced, Trijunction repulsed two more attacks. The fate of Walong, however, was by then sealed.

Around 0300 hours on 16 November the Chinese began a series of co-ordinated attacks on both sides of the Lohit River. Combined with the frontal attacks was an enveloping move from the West. Their aim was to reach the air-strip and the junction of the Lohit with the Yepak River, both South of Walong, so as to cut off the Indians’ retreat. Indian troops fought with determination but superior numbers and better weapons carried the day.

| Editor’s Pick |

At their company localities, 4 Sikh withstood enemy attacks with great courage. Regardless of the odds, they fought on; in some cases whole platoons were wiped out but did not surrender. The Gorkhas fought their hardest action at the Ladders’ position. This locality on the Kibithu-Walong track, which ran along the West bank of the Lohit, got its name from the steps cut into a vertical rock-face. The Gorkhas’ bunkers in this position were virtually rock-caves, impervious to artillery fire from the West bank. Indian Para field guns and mortars and medium machine guns, placed East of the Lohit, supported this position. As long as the Indian defence East of the river held out, the Ladders’ position was safe.

The Chinese had attacked the Ladders on the morning of 15 November, but suffered heavily in a frontal assault. Thereafter, they began to blast the Gorkhas’ bunkers with bazooka fire. They attacked Ladders again that night but were beaten back. The company commander now asked 4 Sikh for reinforcements as the company was under command of that battalion. However, the Sikhs were themselves hard-pressed and could not spare any men.

The withdrawal order did not reach them and most of them were taken prisoner.

On the morning of 16 November, the Gorkhas at the Ladders could watch the attack develop on the Sikhs’ position East of the river. The Chinese crossed over for the attack in large numbers from the West bank in their rubber dinghies. By 0800 hours they had overrun the Sikhs’ company position. Then they placed their direct fire support weapons on the East bank and began to shell Ladders. One by one, the Gorkhas’ bunkers were knocked out but the survivors stayed put. The withdrawal order did not reach them and most of them were taken prisoner.

Due to the manner in which the Indian positions were sited, an orderly withdrawal was out of the question. The battle ended with the Gunners of 17 (Para) Field Regiment firing off their remaining ammunition from their gun-positions on both sides of the Lohit. The Heavy Mortar Battery had earlier abandoned its pieces when the Chinese advanced towards its positions since it had run out of ammunition completely (see Fig.). The withdrawal order was given by Rawlley at 1100 hours on 16 November.

Brigadier Rawlley intended to make a stand on the Yepak but the Chinese forestalled him.

Brigadier Rawlley intended to make a stand on the Yepak but the Chinese forestalled him.

“They were already there and ambushed the withdrawing troops. It was here that the Chinese took most of their prisoners; units broke up into small parties and the long trek to Teju began. The leading troops arrived there on 24 November. When a count of heads was carried out at Teju on November 27, a total of 1,843 all ranks were present with 11 Brigade”.30

The trek from Walong was arduous. Many of the men had to go without food for several days. Stragglers continued to join their units for some days. The Chinese ended their pursuit of the withdrawing troops short of Hayuliang.

As for the remaining two frontier divisions of NEFA, the Chinese entered the Siang Divisions on 16 November and took Gelling, Tuting, Machuka and some other posts in its Northern portion. In the Subansiri Division, they overran the Indian posts at Asafila, Tasking and Limeking.31

LADAKH

It is refreshing to turn to Ladakh from the unrelieved litany of disasters in NEFA. Here too the Chinese took what lay within their claim-line. But good leadership ensured that men were not ordered to shed their blood in defence of territory that was of no tactical importance. At the same time, the enemy was made to pay heavily for his gains. The Indian Army is justly proud of the gallantry shown by the officers and men of 114 Brigade at the Battle of Chushul.

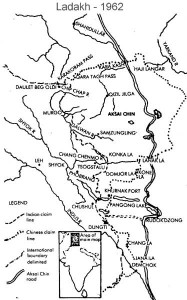

We have earlier noted how Western Command had asked for an infantry division with four brigades and supporting arms to meet the Chinese on equal terms. However, till the end of September 1962, Ladakh had only 114 Infantry Brigade with two regular battalions – 1/8 Gorkha Rifles and 5 Jat. These two battalions and the Jammu & Kashmir Militia were strung out on posts and picquets throughout Ladakh, from Daulet Beg Oldi in the North to Demchok in the South (see Fig. 9.5). Most of these posts were there only to show possession of territory. In case of hostilities, all they could do was to serve as warning posts. Brigadier T.N. Raina (later General Raina, mvc) took over command of 114 Brigade in the third week of September.

According to the Indian Government’s estimate, the Chinese were not expected to react strongly in Ladakh to Operation ‘Leghorn’. Hence the lack of promptness in reinforcing this sector. The first indication of this was the arrival of 13 Kumaon at Leh on 2 October, together with a platoon of 1 Mahar (machine guns). Even at this stage, there was no inkling of Chinese designs and 13 Kumaon was told that it might move to Chushul in March 1963.When the Chinese struck in the early hours of 20 October, Indian troops at the higher posts had already begun their annual thinning out for the winter. The attacks came simultaneously against many of the forward posts. In the North, the posts on the Chip Chap River, East of Daulet Beg Oldi, were among the first to be attacked. The Jammu & Kashmir Militia, who were manning them, fought stubbornly. But the Chinese had brought up enough strength to overwhelm them and they were ordered to withdraw to Daulet Beg Oldi. Two days later, when the Chinese threatened to encircle Daulet Beg Oldi, the garrison there was told to withdraw along the Chip Chap and Shyok Rivers to lay back positions at Thoise, North of Leh.

According to the Indian Government’s estimate, the Chinese were not expected to react strongly in Ladakh to Operation ‘Leghorn’. Hence the lack of promptness in reinforcing this sector. The first indication of this was the arrival of 13 Kumaon at Leh on 2 October, together with a platoon of 1 Mahar (machine guns). Even at this stage, there was no inkling of Chinese designs and 13 Kumaon was told that it might move to Chushul in March 1963.When the Chinese struck in the early hours of 20 October, Indian troops at the higher posts had already begun their annual thinning out for the winter. The attacks came simultaneously against many of the forward posts. In the North, the posts on the Chip Chap River, East of Daulet Beg Oldi, were among the first to be attacked. The Jammu & Kashmir Militia, who were manning them, fought stubbornly. But the Chinese had brought up enough strength to overwhelm them and they were ordered to withdraw to Daulet Beg Oldi. Two days later, when the Chinese threatened to encircle Daulet Beg Oldi, the garrison there was told to withdraw along the Chip Chap and Shyok Rivers to lay back positions at Thoise, North of Leh.

On the Northern shore of the Pangong Lake, India had two posts at Sirijap. They formed the first line of defence of Chushul from the North and were thus of vital importance. Held by a company of 1/8 Gorkha Rifles under Major Dhan Singh Thapa, Sirijap came under fierce attacks from the Chinese on 21 October. The Gorkhas threw back the first attack which was launched after heavy shelling. Though the enemy suffered heavily, it came back in larger numbers after more shelling. The Gorkhas beat back this attack as well.By then casualties had greatly depleted the Gorkha company. The men under Dhan Singh Thapa were, however, a determined lot. When the Chinese attacked once again, they continued to give battle as long as any of them remained on their feet. When the position was finally overrun, Dhan Singh Thapa got out of his trench and killed several of the enemy before he was overpowered and taken prisoner. His courage and exemplary leadership won Dhan Singh Thapa India’s highest award for gallantry. This was the first award of the PVC in Ladakh. Only seven men came back from Sirijap.

On the Northern shore of the Pangong Lake, India had two posts at Sirijap. They formed the first line of defence of Chushul from the North and were thus of vital importance. Held by a company of 1/8 Gorkha Rifles under Major Dhan Singh Thapa, Sirijap came under fierce attacks from the Chinese on 21 October. The Gorkhas threw back the first attack which was launched after heavy shelling. Though the enemy suffered heavily, it came back in larger numbers after more shelling. The Gorkhas beat back this attack as well.By then casualties had greatly depleted the Gorkha company. The men under Dhan Singh Thapa were, however, a determined lot. When the Chinese attacked once again, they continued to give battle as long as any of them remained on their feet. When the position was finally overrun, Dhan Singh Thapa got out of his trench and killed several of the enemy before he was overpowered and taken prisoner. His courage and exemplary leadership won Dhan Singh Thapa India’s highest award for gallantry. This was the first award of the PVC in Ladakh. Only seven men came back from Sirijap.

The Galwan Post had been taken over by 5 Jat in the first week of October. The Chinese had wiped out this post. Kongka, which had been in the news in 1959, suffered the same fate. The Hot Springs Post was withdrawn, and Demchok also fell.

Prior to the invasion, the airfield at Chushul seldom received more than one aircraft a day. It had now to cope daily”¦

After the fall of Sirijap, it was decided that the troops North of the Pangong Lake should withdraw. Two storm boats of 36 Field Company assisted the withdrawal. Under enemy fire, they ferried the troops at night across the lake. Unfortunately, one of the boats sank after being hit.

At this stage, Lieutenant General Daulet Singh appreciated that Chushul would be the next enemy objective. It had an all-weather airfield and lay on the route to Rudok, a hundred kilometres to the East as the crow flies. The Chushul Valley is a narrow sandy tract at an altitude of 4,337 metres. At its Northern end is the beautiful Pangong Tso (Lake). On its East and West, the valley is flanked by lofty ranges that rise up to 5,790 metres. There is a parting in the mountains in the East: the Spanggur Gap. Over it runs the route to Rudok, skirting another gorgeous lake, the Spanggur Tso. The Chinese, in their pre-invasion activity, had improved the track right up to the Spanggur Gap. It could even take tanks, The Chushul airfield was near the Southern end of the valley not far from the mouth of the Gap.

The Engineers had earlier converted the 293-kilometre track linking Chushul to Leh via Dungti into an unmetalled road. On 9 October, Daulet Singh had paid a visit to Chushul to assess its capabilities as a defensive position. Reinforcements began to reach Chushul after a few days. By 24 October, 13 Kumaon was deployed at Chushul. Two days earlier, 9 Dogra had begun to fly to Leh. This battalion was later deployed on the Leh-Chushul road. Towards the end of October, 3 Himalayan Division was raised under Major General Budh Singh to assume control of operations in Ladakh; 114 Brigade was made entirely responsible for the defence of Chushul and its tactical Headquarters moved there. The other two brigades of the new division, 70 Infantry Brigade was deployed around Dungti, South of Chushul. Its third Brigade (163) was flown into Leh on 10 November. By then further reinforcements had arrived at Chushul. These comprised a troop from 20 Lancers (AMX Tanks). 38 Field Battery of 13 Field Regiment a troop from 32 Heavy Mortar Regiment. 1 Jat (LI) and Y Company of 1 Mahar machine guns.

Chinese reconnaissance parties would come up, spread out maps, take a good look and go back”.

The Indian Air Force had a big hand in the build-up at Chushul. It flew sortie after sortie to bring troops, tanks, guns and other equipment. Prior to the invasion, the airfield at Chushul seldom received more than one aircraft a day. It had now to cope daily with six AN-12s and about eight C-119 sorties and frequently became unserviceable. The men of 9 Field Company had a hard task keeping it in repair. To assist them, the Divisional Engineers were also diverted to this task.

As a subaltern in the Kumaon Regiment, Raina had fought the Japanese in several actions in Burma. That experience now served him well. Under his leadership, 114 Brigade began to prepare for the defence of Chushul. He was untiring in his efforts and visited each locality to make sure that it was well sited and the men had all their requirements. That he was able to infuse into his command the spirit that induces men to take on any odds became evident when the battle began. Describing the situation on the eve of the Battle of Chushul, the brigade’s war diary records: “Our troops were well dug down, their arms tested, their ammunition next to them and their hearts all set to face the Yellow Peril”.32 All weapons in the brigade had six second-line scales of ammunition, besides the first-line scale.

| Editor’s Pick |

The brigade held a frontage of 40 kilometres. Building of defences on the heights around Chushul had not been easy, the only means of transport being yaks and ponies hired from the local Ladakhis. The defences were mainly arrayed against the Spanggur Gap. The recoilless guns of three infantry battalions were pooled to ensure concentrated fire on the Gap. The guns of the field battery and the tanks were also trained on this vital ground. North of the Gap was a relatively high feature called Gurung Hill (4,809 metres). This feature, Gun Hill and the Gap were made the responsibility of 1/8 Gorkha Rifles. Mugger Hill (5,182 metres) overlooked the Gap from the South and was held by two companies of 13 Kumaon.

Further South lay Rezang La (5,005 metres) which overlay a track from Tibet that skirted the Eastern shore of the Spanggur Tso and did not touch the Gap. One company of 13 Kumaon held Rezang La. To guard the Northern approaches to Chushul, 1 Jat (LI), together with attached troops, was deployed in the Tokung area. The brigade’s fourth battalion,5 Jat, guarded the Southern approaches and its companies were positioned around Tsaka La, on the Leh-Chushul road. All infantry positions were protected by mines and wire. Dummy guns and tanks were positioned to mislead the enemy. These dispositions then formed the outer defensive perimeter guarding the Brigade’s vital ground – Chushul and its airfield.

The Chinese too had been preparing. Indian observation posts watched their build-up day after day.

“Their lorries came right up to their post at Spanggur. They did a lot of blasting, and their boats were seen to ply on the Spanggur Tso at night. The area that seemed to get the maximum attention from them was the Spanggur Gap. Chinese reconnaissance parties would come up, spread out maps, take a good look and go back”.33

This was in fact a ruse. When they attacked, the Chinese did not attempt a breakthrough at the Gap.

The shelling was particularly intense at Rezang La: the Chinese were determined to take it at any cost.

18 November 1962 was a Sunday. The morning was bitterly cold, and visibility down to 350 metres. The battle that was fought that day was perhaps unique in the history of warfare. Never before had a major action been fought at such heights and with such ferocity. The Chinese began with a ‘silent’ attack on Rezang La in the early hours of the morning. They had brought up their troops during the night in order to surprise this isolated company locality. Ten kilometres from 13 Kumaon’s Headquarters, Rezang La was held by C Company of the battalion and had no artillery support.

Several gullies ran down from the upper reaches of Rezang La towards the Spanggur Tso. At about 0400 hours a patrol spotted a large body of the Chinese scrambling up the gullies and gave the alarm. Within minutes; every man in the company was at his fire position. Under Major Shaitan Singh, a Rajput from Jodhpur, the company at Rezang La had been brought to a state of absolute readiness. The gullies had been ranged in and all of Shaitan Singh’s light machine guns and mortars were now trained on them. As the Chiniese came within range, the Kumaonis let them have it. ‘Many of them fell; others continued to move up. But with every weapon in C Company firing, the gullies in front of the three platoons were soon full of dead and wounded chinese’.34

Their surprise attack having failed, the Chinese now began a massive shelling of the whole front: Gurung Hill, the Gap, Mugger Hill and Rezang La. The shelling was particularly intense at Rezang La: the Chinese were determined to take it at any cost. To destroy the Kumaoni bunkers, they brought up 75-mm and 57-mm recoilless guns on wheelbarrows to the flanks of the company and tired them en masse. They also used a certain number of 132-mm rockets.

No bunker could stand this onslaught. The corrugated iron sheets covering the bunkers were smashed to bits and the ballis reduced to matchwood. Under cover of the shelling, about 600 of the Chinese reached the flanks and attacked the two forward platoons simultaneously. While the Indians were fighting this assault, a Chinese column managed to reach the rear of the company. Under attack from three sides, the gallant Kumaonis put up a brave fight. ‘Eventually, post by post, section by section and platoon by platoon, the company was overrun’. By 0900 hours the Chinese had taken Rezang La.The bitterness of the fighting is evident from the casualties suffered by both sides. Of the Kumaon company, only 14 survivors reached the battalion, all of them wounded. This was out of a total of 1 officer, 3 jcos and 124 other ranks who had gone into battle that morning. According to the estimates of 114 Brigade, the Chinese suffered about 300 casualties in their attack on Rezang La.

No bunker could stand this onslaught. The corrugated iron sheets covering the bunkers were smashed to bits and the ballis reduced to matchwood. Under cover of the shelling, about 600 of the Chinese reached the flanks and attacked the two forward platoons simultaneously. While the Indians were fighting this assault, a Chinese column managed to reach the rear of the company. Under attack from three sides, the gallant Kumaonis put up a brave fight. ‘Eventually, post by post, section by section and platoon by platoon, the company was overrun’. By 0900 hours the Chinese had taken Rezang La.The bitterness of the fighting is evident from the casualties suffered by both sides. Of the Kumaon company, only 14 survivors reached the battalion, all of them wounded. This was out of a total of 1 officer, 3 jcos and 124 other ranks who had gone into battle that morning. According to the estimates of 114 Brigade, the Chinese suffered about 300 casualties in their attack on Rezang La.

Shaitan Singh had received a burst in his arm in the later stages of the battle. After most of the men from his centre platoon and Company Headquarters were either killed or wounded, he was persuaded by his Company Havildar Major Harphul Singh to withdraw along with the others who could walk. While he and his party were on their way, they were spotted by the enemy. Harphul Singh fell mortally wounded and Shaitan Singh received a burst in the abdomen.

Enemy casualties at Gurung Hill were estimated at 500. Indian casualties totalled 39: 26 killed or missing and 13 wounded.

‘The remaining two men of the party bandaged his wound and picked him up, descended into one of the ravines that led to the company’s base. But they had not gone far when they were caught in the crossfire of enemy automatics’. Shaitan Singh realized that there would be no chance of escape for even these two men if they had to carry him. ‘He ordered them to leave him where he was and save themselves. Retuctantly, they left. Three months later, his body was found at that very spot’. Shaitan Singh’s stand at Rezang La earned him the PVC from the Indian Government.

Gurung Hill came under attack from Chinese infantry around 0630 hours on 18 November. By then their artillery and mortars had lifted their fire from the forward Indian positions and begun to shell targets in the rear. Gurung Hills was dominated by Black Hill. The latter was in Chinese hands. Gurung Hill was held by 1/8 Gorkha Rifles with two companies, less a platoon. They were supported by a section each of medium machine guns and 3-inch mortars and an artillery observation party was also positioned with them. Under cover of their shelling, a company plus of the Chinese were seen to roll down from Black Hill to the Gorkhas’ position. Second-Lieutenant S.D. Goswamy, the artillery observation officer, was ready for them, and directed well-aimed artillery fire on them. The impact was sudden and devastating; the remnants of the first wave were hurled back to Black Hill.

Ten minutes later, a second assault wave of the remaining battalion of the enemy was seen advancing from the same direction. The curtain of artillery fire continued, with the tanks, 3-inch mortars and the medium machine guns now joining in. However, even this combined firepower did not daunt the Chinese. By 0930 hours a portion of the defences had been overrun. However, when they advanced towards the remaining defences, fire from the tanks effectively stopped them and they made no further infantry attacks that day. The artillery observation party remained in position till the enemy had reached within 50 metres of it. After Goswamy was wounded by a grenade, his assistant took over and kept directing the fire of his guns till the very end. Except for Goswamy, the entire observation party was wiped out.35 He was awarded the MVC.

| Editor’s Pick |

After lifting their fire from the forward Indian positions, the Chinese turned their artillery and mortars on the airfield, the dummy tanks and gun positions, the Headquarters of 13 Kumaon and the Chushul-Tsaka La road. Though the shelling was heavy it did not do much damage. Some 600 shells landed around 13 Kumaon’s Headquaters, but not a single casualty occurred. Shelling of the remaining portion of Gurung Hill continued till the afternoon, when there was a lull. During the night the Chinese shelled the airfield intermittently.

On 19 November, around 1030 hours, the Chinese formed up to attack the remaining portion of Gurung Hill. The tanks and the artillery again stopped the enemy. The Chinese, however, bided their time. They attacked yet again in the afternoon, under cover of snow and a heavy mist that occurred around 1400 hours. It was a two-pronged assault and came in such strength that the position fell at 1530 hours.

Enemy casualties at Gurung Hill were estimated at 500. Indian casualties totalled 39: 26 killed or missing and 13 wounded.

After the battle, enemy movement was observed in the direction of the airfield. The Chinese were apparently aiming to roll down in strength from Gurung Hill and another position during the night with a view to cutting off Indian troops in the Spanggur Gap and on Mugger Hill. The Indians had decided earlier that in such a contingency it would be futile to hold on to these positions. Raina accordingly gave orders to commence thinning out at last light. Similar orders were sent to the troops holding the line between Tokung and Gurung Hill.

The result of his timely action was that the whole brigade, with practically its entire equipment and stores, was re-established in its new defences around Chushul village by the morning of 20 November. On 18 November, as part of a planned withdrawal, about a hundred second- and first-line vehicles had been sent back from Chushul to Dungti to avoid their falling into enemy hands.

As the reader would have noted, such moves, planned and deliberate, were conspicuous by their absence in NEFA. Much of the credit for organizing the defences of Chushul and for saving the village and the airfield goes to Brigadier Raina. The Indian Government recognized this by conferring upon him the MVC.

As the reader would have noted, such moves, planned and deliberate, were conspicuous by their absence in NEFA. Much of the credit for organizing the defences of Chushul and for saving the village and the airfield goes to Brigadier Raina. The Indian Government recognized this by conferring upon him the MVC.

14 Brigade remained undefeated. The fighting in Ladakh ended with China’s unilateral cease-fire declaration. The new Chinese Line of Actual Control now gave full security to the Aksai Chin Road running in Indian territory.

NOTES

- Himalayan Battleground, by Fisher, Rose and Huttenback, p. 135.

- India’s China War, by Maxwell, p. 293.

- Himalayan Blunder, by Brigadier J.P. Dalvi, p. 130.

- The Untold Story, by Kaul, p. 341

- Himalayan Blunder, by Dalvi, p. 150.

- The Untold Story, by Kaul, p. 356.

- An Assistant Political Officer came up a few days later for this purpose but was stopped en route when a radio signal was received forbidding such talks. The Chinese request had been conveyed to Nehru, then in London, and the refusal has been attributed to him.

- Some sources put the incident on the previous night.

- Himalayan Blunder, by Dalvi, pp. 235–6 and 239–40.

- The Untold Story, by Kaul, pp. 36–8.

- Ibid., p. 372.

- This officer was Brigadier General Staff at Headquarters 4 Corps.

- He was the Chief Engineer at Headquarters 4 Corps.

- The Untold Story, by Kaul, p. 386.

- Ibid., p. 387.

- Himalayan Blunder, by Dalvi, p. 330.

- The Untold Story, by Kaul, pp. 388–9.

- Himalayan Blunder, by Dalvi, p. 341.

- Y.B. Chavan, then Chief Minister of Maharashtra, was named as Menon’s successor but he took over his new charge only after the cease-fire.

- The Untold Story, by Kaul, p. 398.

- The technique of infiltrating the Indian flanks was continued by the Chinese in the second phase of their operations. They had evidently given a good deal of thought to this manoeuvre. In the Second World War, the Japanese had hoodwinked an astute general like Slim with this technique. They attacked his flank in Imphal and Kohima after bringing up two infantry divisions along very difficult tracks that led through the jungle from the Chindwin River. Slim had estimated that the Japanese would not be able to bring up more than a brigade that way. Their feat surprised him and the battles around Kohima and Imphal were the most crucial in the Burma campaign. The fate of Assam had hung in the balance for many weeks. Slim had the resources to deal with his adversary’s unexpected manoeuvre; 4 Corps neither had the resources, nor someone even approaching Slim’s calibre to control the situation that resulted from Chinese thrusts against 4 Division’s flanks.

- Tse La (4,754 metres) lies North-East of Se La.

- India’s Defence Problem, by Khera, p. 230.

- In other sectors too, Chinese advance elements used men dressed in local attire to confuse Indian troops.

- The Untold Story, by Kaul, p. 413.

- Quote from The Red Eagles.

- The ambush took place after the cease-fire.

- Quote from The Red Eagles.

- Chinese Invasion of NEFA, by Major S.R. Johri, p. 211.

- Quote from Valour Triumphs.

- Chinese Invasion of NEFA, by Johri, pp. 250, 254.

- Quote from Valour Triumphs, p. 246.

- Ibid., p. 248.

- Ibid., p, 250.

- Red Coats to Olive Green, by Longer, p. 388.

When,,,, photo of Brigadier Hoshiar Singh shown to one of the pow after his sacrifice,,, the chinese officer asked …. do you know this officer ?… he is now …no more…

face of indian Jwan got SHOCKED,,,

oh !!! u know this man…tell me about him…

…he replied… his wardi shows …..

he is an indian officer …we salute and proud of him.

jai hind….

to immediate officer of this jawan… who really remembers his great hero till now. .

I visited NEFA IN 1987 after a gap of 25 years of operations and had carried out recovery operations of equipment after declaration of ceasefire by Chinese.

When I was visiting Rupa few people stationed there showed the place where Brigadier Hoshair Singh was tied behind a Chinese Jeep and dragged till he passed away.

While reading one of the accounts it said that he was shot dead.

What is the truth ?