The Chinese reaction to the setting up of a post by India at Che Dong was a calculated move. By this time, China appears to have decided on a full-scale campaign to assert her territorial claims. According to independent observers, the Chinese would have sought provocations elsewhere if no trouble had taken place at Che Dong.l Brigadier J.P. Dalvi, who was taken prisoner during the hostilities, also arrives at the same conclusion. While he was in their custody, he saw the elaborate arrangements that the Chinese had made for 3,000 prisoners.

Che Dong was no prominent landmark, or a feature of tactical importance. It was merely a cluster of herders’ huts built by Monpa tribesmen of the region. The huts lay a short distance from the spot where the boundaries of India, Bhutan and Tibet meet. In fact 33 Corps had ordered that the post should be set up at the trijunction itself. However, the Assam Rifles’ detachment that went to establish it found the site unsuitable owing to its altitude and inaccessibility and selected Che Dong instead. The place lay on the lower slopes of a range called Tsangdhar, which runs Eastwards from the knot of mountains that form the trijunction. The post faced the Thag La Ridge. Between Thag La and Tsangdhar is a mountain stream, called the Namka Chu, which flows from West to East.

Click to buy: Indian Army After Independence

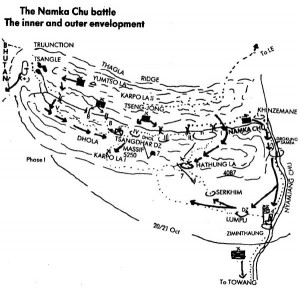

Here, a word about the Namka Chu. Its source lay North-West of Che Dong among a group of lakes near Tsangle, at an altitude of 4,590 metres. About 26 kilometres in length and 6 to 16 metres in width, it ran in a deep, boulder-strewn bed with banks six to ten metres high. By the time it joined the Nyamjang Chu near Khinzemane, it dropped some 2,620 metres. Though fast-flowing, it was fordable, except during and immediately after the monsoon and when the snows melted. The river valley was thickly wooded; movement was difficult, except on the tracks, and fields of fire were limited.

How did Thag La come to be treated as Indian territory when it was shown North of the McMahon Line on the Survey of India maps? The answer is to be found in the Simla Convention of 1914.

Local herders had thrown wooden bridges across the Namka Chu for use when it was unfordable. These consisted merely of logs tied together and slung across the stream. There were five of these bridges and they came to be numbered from East to West as I, II, III, IV and V. Following the Hathung La route to Dhola Post, the track hit Bridge I. Across it, the track forked. Going Eastwards one reached Khinzemane; going North-West along the river and recrossing to the South at Bridge II, one reached Dhola Post opposite Bridge III. A short distance from the post was Bridge IV, and close to Tsangle was Bridge V. Between Bridges IV and V were two more bridges: Temporary Bridge and Log Bridge. The bridges, of no use to man or beast when the river was not in spate, became vital points to be defended to the utmost. In October one could walk across the river without using the bridges.

Thag La is higher than Tsangdhar and runs almost parallel to it. Thus, the Che Dong Post was overlooked by Thag La as also the Tsangdhar range itself. Sited thus, it served no purpose. In case the Army wanted to set up a post in the region, it should have been sited either upon Thag La or atop Tsangdhar.

The Assam Rifles were responsible for setting up border posts. However, as the latter were under the Army’s operational control, it helped in their establishment. While this particular post was being set up, the officer entrusted with the task was questioned over the radio by the General Officer Commanding 4 Infantry Division, Major General Niranjan Prasad, as to why a site shown North of the McMahon Line on the map was selected. In reply he was told that according to the Intelligence Bureau representative with the party, even the Thag La Ridge was Indian territory. In most contemporary records, the post is incorrectly mentioned as the Dhola Post. The Dhola feature, in fact, lay a few kilometres South of the McMahon Line but the man on the spot somehow gave this name to the post at Che Dong and it stuck.

Prasad was unhappy about this post. From the middle of July 1962, he made several representations to the effect that it should either be withdrawn or moved forward to a tactically sound position on the Thag La Ridge, in case that ridge was Indian territory. His objections were conveyed to higher authorities, right up to Army Headquarters and the Defence Ministry but no reply was received till 12 September, when he was told that Thag La was indeed Indian territory and the Army must exercise the country’s rights over it. The decision came too late; by then, the Chinese were already on Thag La in strength, with regular People’s Liberation Army first-line troops.

| Editor’s Pick |

How did Thag La come to be treated as Indian territory when it was shown North of the McMahon Line on the Survey of India maps? The answer is to be found in the Simla Convention of 1914. At this Convention, Sir Henry McMahon had generally taken the Himalayan watershed as the frontier. In fact, one of the objectives of the Indian Government at this convention was to secure a strategic watershed boundary between the two countries. Where the boundary terminated in the West, ‘there was no watershed to be followed, and McMahon drew his line along what his maps showed as outstanding ridge features’.2 However, after Independence when the Indian authorities began to take a closer look at the country’s Northern borders, it was found that on transposing the McMahon Line to the ground from its map coordinates, the line would not run along the highest ridge in the area. The Thag La Ridge, lying four to five kilometres North of the map-marked McMahon Line, was the highest feature and India decided to treat the crest of this ridge as the boundary.

The Army authorities, from Army Headquarters down to brigade Headquarters, were apparently guided by this decision when the post at Che Dong was set up. Had they known that Thag La was Indian territory, the story of the 1962 hostilities might have been different.

The Indian Government thus knew of the Chinese stand on Thag La and it might have been more expedient to let sleeping dogs lie than to set up a post at Che Dong

As it was, Thag La was important for the Chinese too. On its Northern slopes was Le, a large Tibetan village, which was the obvious site for a Chinese forward base for any operations against India in this sector. Besides, there had been trouble over the ridge earlier.

In August 1959, the Assam Rifles set up a checkpost at Khinzemane, on the South-Eastern tip of the Thag La Ridge where the Namka Chu joins the Nyamjang Chu, a river that flows from Tibet into NEFA. The Chinese reacted sharply. About 200 of them appeared on the scene and pushed the Assam Rifles’ men to the bridge on the Nyamjang Chu at Drokung Samba, a few kilometres to the South which they claimed was the boundary according to the McMahon Line. Thereafter, the Chinese withdrew. A couple of days later, the Assam Rifles returned to Khinzemane. The Chinese again tried to push them out but this time the Assam Rifles made it clear that they would resist. The Chinese made no further attempt to remove the Khinzemane post but protest notes began to fly between the two Governments. A stalemate followed after India proposed discussions on the exact alignment of the boundary at Khinzemane and other disputed points.

The Indian Government thus knew of the Chinese stand on Thag La and it might have been more expedient to let sleeping dogs lie than to set up a post at Che Dong, a place that was nothing but a death-trap for the men guarding it.

Let us now take a look at the military situation in the sector as on 9 September 1962, the day Defence Minister Krishna Menon ordered the eviction of the Chinese facing the Assam Rifles’ post at Che Dong.

It was almost three years since 4 Division had been made responsible for the defence of NEFA. During this period, there had been no increase in the strength of the division or in its striking capacity. The Divisional Headquarters was still at Tezpur and the Headquarters of 7 Brigade was at Towang. Major General Niranjan Prasad had taken over command of the division in May 1962. Brigadier John Parashram Dalvi had assumed command of 7 Brigade a few months earlier. He had just finished a stint at 15 Corps Headquarters as Brigadier-in-Charge Administration. Earlier, he had commanded a Guards’ battalion.

The Border Roads Organization, set up in 1960, made commendable efforts after they took over the task of road-building in this sector. But it was impossible for this organization to complete in two years a task that would normally take twelve. By September 1962, a one-ton road was built upto Towang. As it had to be laid across the grain of the Southern Himalayas, it would take many years to settle down and was at the time only fit as a fair-weather road. Monsoon rains had damaged it extensively, large chunks having been washed away.Taking a look at the terrain that this road traverses, one becomes aware of the tremendous difficulties the Army engineers faced in building it. From the foothills of the Himalayas, Nordi of Misamari, it climbs 2,743 metres above sea-level to reach a place called Eagle’s Nest; a further climb of about 200 metres takes one to Bomdi La. Thereafter, there is a drop to Dirang Dzong, situated at 1,676 metres. Then begins the ascent to Se La, perched at 4,180 metres followed by a steep drop to Jang (1,524 metres), and finally the climb to Towang (3,048 metres).

The Border Roads Organization, set up in 1960, made commendable efforts after they took over the task of road-building in this sector. But it was impossible for this organization to complete in two years a task that would normally take twelve. By September 1962, a one-ton road was built upto Towang. As it had to be laid across the grain of the Southern Himalayas, it would take many years to settle down and was at the time only fit as a fair-weather road. Monsoon rains had damaged it extensively, large chunks having been washed away.Taking a look at the terrain that this road traverses, one becomes aware of the tremendous difficulties the Army engineers faced in building it. From the foothills of the Himalayas, Nordi of Misamari, it climbs 2,743 metres above sea-level to reach a place called Eagle’s Nest; a further climb of about 200 metres takes one to Bomdi La. Thereafter, there is a drop to Dirang Dzong, situated at 1,676 metres. Then begins the ascent to Se La, perched at 4,180 metres followed by a steep drop to Jang (1,524 metres), and finally the climb to Towang (3,048 metres).

The total distance from the foothills is only about 291 kilometres but it takes several days to cover. Considering the necessity for acclimatization of troops inducted from the plains, quick reinforcement of the theatre was impracticable. Also, till then, no staging facilities had been provided on the route and there were no replenishment dumps. In fact, a journey to Towang was a nightmare.

Considering that the McMahon Line in Kameng stretched for about 150 kilometres, this solitary brigade was woefully inadequate for these tasks.

Beyond Towang, ponies, mules and porters were the only mode of transport. Two main routes led from here into Tibet. One led North, by way of Pankentang, Tongpeng La and Bum La to Tsona Dzong. Its subsidiary also reached Bum La direct from Jang, bypassing Towang. The other route followed the Nyamjang Chu most of the way. Lum La, about 35 kilometres West of Towang, was the first important valley to reach Shakti, another 28 kilometres upstream. Keeping along the river for another 36 kilometres, one reached Khinzemane. From there a track over the Thag La Ridge led to Le.

To reach the Assam Rifles’ post at Che Dong, one had to leave the Shakti-Khinzemane route about 5 kilometres short of the point where the Namka Chu meets the Nyamjang Chu, go West to Lumpu (3,048 metres), whence a path led North across Hathung La (4,396 metres) to Che Dong (see Fig. 9.1). The last leg of this route ran along the North bank of the Namka Chu, right under the Chinese positions on Thag La. Indian troops had, therefore, to use an alternative route later on. This was longer and more difficult. It led Westward from Lumpu by way of Karpo La I (5,250 metres,) on to the Tsangdhar range and thereafter descended steeply to the Namka Chu. From the Tsangdhar Northern face another faint track of sorts led towards the trijunction.

Besides the main routes mentioned above, there were several tracks in India and Tibet that joined them either laterally or longitudinally at different points over little known passes and alignments. Also, there were many footpaths in the region that traversed the India-Bhutan boundary. For the Chinese, access to the Namka Chu Valley was comparatively easy. From Thag La, their forward base at Le was only a three-hour march away. During their offensive, they extended their motor road from Tsona Dzong to Towang over Bum La.

The tasks given to 7 Brigade bore no relationship to its capability. Its primary task was spelt out as the defence of Towang. Preventing any penetration of the McMahon Line, setting up of and assistance to the Assam Rifles’ posts, were its other tasks. Considering that the McMahon Line in Kameng stretched for about 150 kilometres, this solitary brigade was woefully inadequate for these tasks. As it was at the time of the Che Dong incident, it had only two infantry battalions: 9 Punjab and 1 Sikh, both at Towang. Its third battalion – 1/9 Gorkha Rifles – was at Misamari. This battalion had completed its three-year tenure in NEFA and was under move to Yol, where the men’s families were. The battalion earmarked to replace the Gorkhas – 4 Grenadiers – had not yet arrived.The training of 7 Brigade had been neglected. It had done no collective training since its arrival in NEFA. Its men had been employed on tasks unconnected with the brigade’s role. Large numbers were employed for building a helipad at Towang and for the construction of shelters for themselves. The two battalions now with the brigade had a strength of only about 400 men each.

The tasks given to 7 Brigade bore no relationship to its capability. Its primary task was spelt out as the defence of Towang. Preventing any penetration of the McMahon Line, setting up of and assistance to the Assam Rifles’ posts, were its other tasks. Considering that the McMahon Line in Kameng stretched for about 150 kilometres, this solitary brigade was woefully inadequate for these tasks. As it was at the time of the Che Dong incident, it had only two infantry battalions: 9 Punjab and 1 Sikh, both at Towang. Its third battalion – 1/9 Gorkha Rifles – was at Misamari. This battalion had completed its three-year tenure in NEFA and was under move to Yol, where the men’s families were. The battalion earmarked to replace the Gorkhas – 4 Grenadiers – had not yet arrived.The training of 7 Brigade had been neglected. It had done no collective training since its arrival in NEFA. Its men had been employed on tasks unconnected with the brigade’s role. Large numbers were employed for building a helipad at Towang and for the construction of shelters for themselves. The two battalions now with the brigade had a strength of only about 400 men each.

| Editor’s Pick |

Several factors were responsible for this. Both had rear dumps at Misamari and men had to be kept there to look after the battalion equipment and stores. Many men were away on courses and leave and, like other units in the Army at the time, these battalions had been ‘milked’ for new raisings. Then there was the question of maintenance and supply. All troops at Towang and beyond were on air-supply. This restricted the number that could be maintained there.

Lack of intelligence about Chinese intentions and their preparations was a major deficiency on the Indian side. In the Indian Army’s plans, it was assumed that the Chinese would not be able to deploy more than a regiment (brigade) against Kameng.3 Apparently, the assumption was tailored to suit the Indian capability at the time. In the event, the Chinese brought up more than two divisions into Kameng. At best, Indian assessments were guesswork.