When the Constitution was framed, a sub-committee headed by Gopinath Bordoloi was appointed to examine and recommend the constitutional arrangements that would fulfill the aspirations of the tribal population of the Northeast and thus set at rest fears about the possible loss of their unique identity. Recommendations of the Bordoloi sub-committee were extensively debated and incorporated with some amendments into the Constitution as the Sixth Schedule which protected not only the tribal laws, customs and land rights; but also gave sufficient autonomy to the tribes to administer themselves with minimum outside interference. However, as events unfolded, hopes were belied. Tribal insurgencies erupted in Nagaland, Mizoram, Manipur, Assam and Tripura at different points in time. The Mizo insurgency was resolved through a political settlement. The Naga insurgency, the oldest in the Northeast, has been in a state of suspended animation for more than a decade through various ceasefires negotiated from time to time since 1997 but a solution is yet to be found.

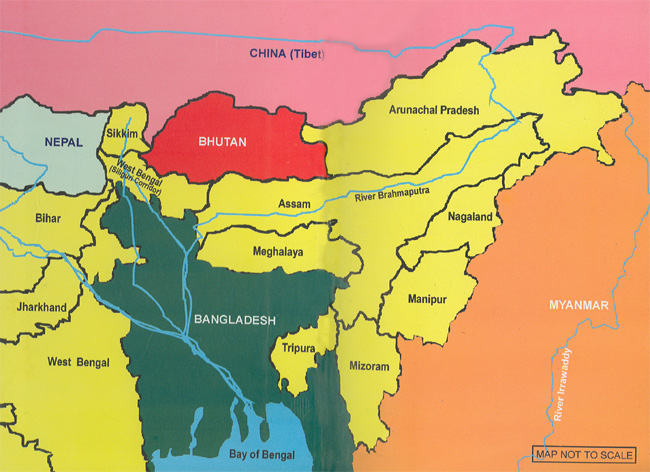

Northeast India covers an area of 255,083 sq. km. It shares 98 per cent of its boundary with four countries. It is connected to the rest of India by 28 km. vide Siliguri Corridor. It comprises seven states which possess a distinct culture, historical traditions and are in different stages of political and economic development. Physiographically, the Northeast comprises three distinct regions – Assam Valley, Purvanchal Region (which includes Nagaland, Tripura, Mizo Hills and Cachar hills and Meghalaya and Mikir Region. The complete area is inhabited by 213 different tribes speaking 325 different dialects.

In an insurgency area, the space is occupied by five actors namely society, insurgents, administration, politicians and security forces. The key to success is to increase the space of the society and reduce that of the insurgents. The six-decade old insurgency in the Northeast continues to endure perhaps on account of failure to manage. Much of what ails the region is the result of a feeling of alienation. The term ‘Northeast’ is not only a physical identity that has been artificially fashioned; but also the one that drives New Delhi’s political, economic and security policies for the region. The policies that New Delhi has been adopting for resolving the insurgency in the Northeast is a mix of military power, suspension of operations, dialogue and ceasefire.

The ULFA insurgency is still active and has also spread to parts of Arunachal Pradesh…

An Overview of Insurgency in the Northeast

When the Constitution was framed, a sub-committee headed by Gopinath Bordoloi was appointed to examine and recommend the constitutional arrangements that would fulfill the aspirations of the tribal population of the Northeast and thus set at rest fears about the possible loss of their unique identity. Recommendations of the Bordoloi Sub-committee were extensively debated and incorporated with some amendments into the Constitution as the Sixth Schedule which protected not only the tribal laws, customs and land rights but also gave sufficient autonomy to the tribes for self-administration with minimum outside interference. However, as events unfolded, hopes were belied. Tribal insurgencies erupted in Nagaland, Mizoram, Manipur, Assam and Tripura at different points in time. The Mizo insurgency was resolved through political settlement. The Naga insurgency, the oldest in the Northeast, has been in a state of suspended animation for over a decade through various ceasefires negotiated from time to time since 1997 but a solution is yet to be found.

The situation in Manipur is probably the worst. The state presents a rather complex picture of ethnic divisions. The Nagas of Manipur hills who feel closer to their kin of Naga hills (in Nagaland) want to be part of Greater Nagaland. Meities, who constitute over 60 per cent of the total population of Manipur, want to maintain their integrity, but the demands are secessionist in nature. They maintain that Manipur was never a part of India and still is not. The ongoing conflict between the Nagas and Kukis further complicates the situation. The level of violence is quite high. The gravity of the situation may be gauged from the fact that recently a Joint Action Committee constituted by the State recommended that civilians be permitted to possess arms to defend themselves against insurgents.

In spite of the 1988 Accord with the Tripura National Volunteer Force, Tripura is also faced with a low level of insurgency and keeps regressing into ethnic violence from time to time. The State is surrounded by Bangladesh except for a small stretch of the border which it shares with Mizoram and Assam. Due to a large influx of illegal immigrants since 1947, the local tribals in the State have been reduced to a minority. The resultant clash of interest between the tribals and the immigrants is the root cause of insurgency in the state. The most worrisome aspect of the insurgency is the process of ethnic cleansing undertaken by the People’s Front of Tripura that has been targeting Bengalis and forcing them to flee the State.

The discontent in Assam has a long history. The partition of India in 1947 started a process by which Assam continued to shrink in size to what it is today. It also resulted in an increased flow of migrants from the erstwhile East Pakistan and from other parts of India. Re-organisation of the rest of the country on a linguistic basis also had its effects on the aspirations of the people of Assam.

The origins of insurgency in Assam can be traced to the Assam Movement started by the All Assam Gana Sangram Parishad (AAGSP) along with the All Assam Students Union (AASU) in 1979. It was an agitation against the so-called “foreigners” and the demographic changes that had occurred due to the large influx of migrants. The Assam Accord of August 1985 which brought the AASU into power, did not bring peace to the state. Encouraged by the success of the violent means adopted by AASU, another militant organisation – the United Liberation Front of Assam (ULFA), started the agitation for “Swadhin Asom” (Independent Assam).

India, like most other democracies is slow to react to developing internal threat…

The ULFA insurgency is still active and has also spread to parts of Arunachal Pradesh. The Bodo area is slowly becoming a flashpoint again, Bodo People’s Progressive Front, now running the Bodo Territorial Autonomous District Council, is in conflict with the secessionist National Democratic Front of Bodoland, which is observing a truce with the Centre since 2005. The 2003 Bodo Accord has not been able to restore peace in the region. Further, illegal migration from Bangladesh threatens to change the demographic profile of Assam and West Bengal which has serious political and security implications for India. Bangladesh however, refuses to accept that any of its nationals are staying outside its boundaries and is also opposed to fencing the Assam–Bangladesh border. The situation is further compounded by the external linkages with Myanmar and Bangladesh, of various insurgent groups operating in the Northeast. There are reports to suggest that terrorist groups located in Bangladesh, are acting in concert with the Inter Services Intelligence (ISI) of Pakistan for spreading terrorism in India.

The Routine Government Response

Since independence, the situation in the Northeast has been quite delicate. The Sixth Schedule of the Constitution was a major step to address the problems that were foreseen at that point of time. However, since then, there has been no coherent strategy to integrate the region into the national mainstream. The Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act, 1958 (AFSPA) was enacted in 1958, essentially to tackle the situation in Nagaland prevailing at that time and was initially supposed to have remained in operation for one year. The Act continues to be in force and extends to all the seven states in the Northeast. Following large-scale protests in Manipur in 2004, a Review Committee was formed by the Government. No final decision has yet been taken and AFSPA continues to be in force.

Every time there has been an agitation or a movement, the response has been to deploy the Security Forces, mainly the Army, to conduct counter insurgency operations, followed by a protracted dialogue and announcement of large financial packages for development. In the absence of effective governance in these states, the funds have often found their way to the insurgent groups who have given up their ideologies and are indulging in large scale extortions. The victims are the transporters, traders, government employees, public and private enterprises and the common man; none is spared. Their aim is to gain power and to control the parallel economy. Insurgency has become an industry and a way of life. In some cases, insurgents have also enjoyed political patronage.

The only insurgency that has been successfully resolved has been that in Mizoram. The two-decade old insurgency (1966-1986) came to an end with the signing of the Peace Treaty on June 30, 1986. It is perhaps time to re-visit this success story to draw lessons which can be applied elsewhere, albeit with modifications.

Recently, a document called “Northeast Vision 2020” prepared at the behest of the Central Government was released by the Prime Minister. Hopefully, it signifies a new beginning for the troubled region but much would depend on its translation into action.

The impression that India is a ‘soft state’ needs to be dispelled by the Government by demonstrating its resolve, politically, diplomatically and militarily…

New Delhi recognises and governs the Northeast despite its non-homogenous character, only as a fused identity. Consequently, the term “Northeast” is not only a physical identity that has been artificially fashioned, but also one that drives New Delhi’s political, economic and security policies for the region. But the diversity that make up the Northeast are apparent. A Nocte of Arunachal Pradesh has as much in common with a Mising of Assam, as would a Kashmiri Pundit have with a Namboodiri from Kerala, despite the fact that in ordinary comprehension, both Nocte and Mising are tribals, just as, in the case of the comparison that is being made, the Kashmiri and Keralite belong to the Brahmin affiliation. It is such indistinct notations that have provided the region with a sense of false homogeneity and – as aforesaid, the character of a “security zone”, the latter perhaps as a result of New Delhi’s policy towards the encircling nations, propelled to a significant degree by circumspection and the need therefore, to create a buffer region.

Reasons for Insurgency in the Northeast

After partition, the Northeastern Areas (Re-organisation) Act, 1971 created three states – Manipur, Tripura and Meghalaya and two Union Territories, Mizoram and Arunachal Pradesh effective from January 21, 1972. The two Union Territories became states in 1987. All the states in the Northeast are in the grip of insurgency or have been through insurgency in the past. The reasons for these are similar and have been enumerated below:

- The roots of insurgency in the area go back to pre-independence days. The tribes were not brought under a strict political control and rigid regulations. The British tribal policy and Christian education are believed to have queered the pitch for Independent India.

- Setting up of reserved forests by British led to the loss of tribal control over natural resources.

- Migration of people from the plains posing economic, cultural and political threat to the tribals.

- Lack of good governance and transparency,

- Faulty nation-building strategies (economic deprivation).

- Inappropriate development.

- Large-scale unemployment.

- Hostile neighbours extending moral and material support.

- Lack of good leadership and popular support.

- Not anti–India but anti-establishment.

- Money for development never reached the target but was diverted to insurgents by politicians to buy security. There was no shortage of recruits as unemployed educated youth were available to join them.

The Gateway Paradigm – A Necessity to End the Insurgency

And so we have, over the past years – with increasing enthusiasm since the early 1990s – the propagation of a new variant of the ‘development solution’:

- South-east Asia begins in Northeast India.

- For India’s Northeast, the future lies in emotional and political integration with the rest of India an economic integration with the rest of Asia.

- India’s ‘Look East Policy’ is meaningless if it does not have an impact on the Northeast region.

The logic derives exclusively from location and history, with almost no consideration of current imperatives of geopolitics, capacities, governance and security. As one commentator notes, “The economic approach to the problems of the Northeast seems based more on historical romanticism than cold economic facts.” In brief, the argument is:

- The Northeast is land-locked and has been further isolated by partition and the existence of a hostile Bangladesh which blocks access to the Indian mainland, except by a tenuous and uneconomical transportation link through the chicken’s neck or the Siliguri Corridor.

- The Northeast is the ‘hub’ or “tri-junction’ of three great civilizations – the Indian, Chinese and Southeast Asian – with a rich history of cultural and trade relations.

- Historically, this tri-junction was at the hub of the famed Silk Route that enriched the enveloping region, including the Northeast. The locational advantages that fuelled the Silk Route still exist and have been infinitely advanced as a result of the new globalisation of the economy and the revolution in transport and communications.

- The region is also joined by and exists as a natural geographical par of multiplicity of regional economic groupings including:

– The South Asia Growth Quadrangle (Nepal, Bhutan, Bangladesh and Eastern/Northeastern India).

– SAARC (South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation).

– ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations).

– Bangladesh, India, Myanmar, Sri Lanka and Thailand in an incipient Bay of Bengal Community (BIMSTEC).

– Greater Mekong Sub-region (GMS) including Myanmar, the Lower Mekong countries of ASEAN, the new China – Yunnan, Myanmar, Laos, Thailand upper – Mekong quadrangle and the New Mekong – Ganga cooperation project.

– The encompassing Indian Ocean Rim – Association for Regional Cooperation (IOR-ARC) and the trans-Himalayan and pan-Asian links being forged by highway, rail and pipeline connections.

- By ‘opening up’ Eastwards, the Northeast would not only secure “wider market access to some of the fastest growing South East Asian and East Asian economies”, but this market integration would also create greater trade between India and these countries, with the Northeast “serving as a gateway”. This trade would then serve as “a driver of rapid economic development of the region”.

- ‘Export led growth’ has been the ‘centerpiece of industrial policy’ in many countries of Asia, resulting in tremendous development in many countries. This is a model that can be replicated in the Northeast.

- Frontier development in the heartland of continents through the development of commercial nodes in border zones along road, rail or inland water corridors creates the potential for the region to become gateways or entry posts.

- The ‘Look East Policy’ envisages the Northeastern region not as the periphery of India, but as the centre of a thriving and integrated economic space linking two dynamic regions with a network of highways, railways, pipelines, transmission lines, criss-crossing the region.

- The Northeast, in addition to its tremendous locational centrality, has immense resource endowments – particularly in bio-diversity, hydro-potential, oil and gas, coal, limestone and forest wealth, and is ideally suited to produce and process a whole range of plantation crops, spices, fruits, vegetable, flowers and herbs.

A great deal of this rhetoric is well intentioned; in other cases, it is simply facile, glib political postures entirely lacking any connect with the realities of the ground. In all cases, however, it reflects either a purely ‘microeconomic’ orientation, with a deliberate neglect of the peculiarities of the political economy of the region or a deceptive superficiality, again with no reference to the situation on the ground. It is crucial to understand:

- You cannot simply order the various components of this supposed strategy off an a la carte menu. Take the idea of the separation of ‘emotional and political integration’ with India, and ‘economic integration’ with South East Asia. In this fractious region, given the patterns of underlying kinship across national borders and the interests of external powers – including both great and lesser powers in the immediate neighbourhood – how precisely is this to be secured in any but an ideal world?

- Various components of the ‘paradigm’ that has been widely articulated and enthusiastically seized upon need to be evaluated within the realities of the prevailing situation, before large amounts of money and political capital are pumped into another doomed project.

- Specifically and immediately, certain unanswered questions arise out of the present concepts of the ‘bridgehead’ or ‘entrepot’ paradigm and these need to be objectively evaluated.

– Market integration can lead to both trade creation – through the emergence of new industries; and trade destruction – as a result of the demise of inefficient operation due to exposure to more efficient competitors from integrating countries, and advantages of economies of scale that may already exist in these.

– The economic transformations that are catalyzed by ‘integration’ may, in fact, bypass the entire traditional sector and replicate the development of ‘colonial’ sectors, such as tea and oil, which have had a long existence in the region – particularly Assam – with little linkage with domestic local commodity, factor and money markets, few forward and backward linkages to the large local economy, and little impact as a driver of growth and general prosperity.

– India’s relations with neighbouring countries are riddled with political and diplomatic minefields. Bangladesh has had a long history of overt and covert hostility. Border disputes and the memory of 1962 place China in the realm of perpetual suspicion. While India’s relations with Myanmar are friendly, but China’s overwhelming presence in Myanmar will, again, create potential difficulties and areas of suspicion. China’s aggressive expansion across South East Asia and in the Indian neighbourhood is also perceived as a significant threat – both in economic and security terms. Given the existing political relationships in the neighborhood, the actual realisation of trade potential is constrained.

– Most significant, however, is the fact that manufactured goods of local origin comprise little of the existing (formal and informal) trade with the Northeast’s neighbours. While bicycle exports to Bangladesh were thriving, the only bicycle factory in the region, at Guwahati, was shut down, and export requirements were met from elsewhere despite high transport costs. Existing trade, though substantial in local terms, has resulted in nothing more than the emergence of a few trading centres near the borders.

– The capital cost of ‘integration’ and realisation of the Northeast’s potential does not appear to have been realistically factored into the benign projections currently in favour. A few examples are:

(i) `228,000 crore at 2002-2003 prices for full development of hydropower potential.

(ii) The Stillwell Road project is now conceptualised as part of the Trans Asia Express Way and the Trans Asian Railway that could link Southwest Chinese trading centres and the entire South East Asian region. India’s trade with China would then need to cover less than 2,000 km, as against the current 6,000 km trip through the Strait of Malacca. The cost implications would be staggering.

(iii) `93,619 crore at 1996-1997 prices for infrastructure development within India. (High Level Commission to be Prime Minister on Tackling Backlogs in Basic Minimum Services and Infrastructure).

(iv) Current sea transport accounts for as little as five per cent of the landed cost of any commodity – consequently, geographical proximity has little to do with trade, except in limited border trade. It is not clear that the massive investments required for developing the Trans-Asian Road and Rail Links will be forthcoming in any rational economic policy framework, as against ‘historical romanticism’.

– Resource endowment and location themselves are not enough to unleash a dynamic process of economic development or productive integration. The ‘potential’ of the Northeast has always existed – but it has not been realised, and there are overwhelming reasons in the political economy of the region why this is the case.