When the Constitution was framed, a sub-committee headed by Gopinath Bordoloi was appointed to examine and recommend the constitutional arrangements that would fulfill the aspirations of the tribal population of the Northeast and thus set at rest fears about the possible loss of their unique identity. Recommendations of the Bordoloi sub-committee were extensively debated and incorporated with some amendments into the Constitution as the Sixth Schedule which protected not only the tribal laws, customs and land rights; but also gave sufficient autonomy to the tribes to administer themselves with minimum outside interference. However, as events unfolded, hopes were belied. Tribal insurgencies erupted in Nagaland, Mizoram, Manipur, Assam and Tripura at different points in time. The Mizo insurgency was resolved through a political settlement. The Naga insurgency, the oldest in the Northeast, has been in a state of suspended animation for more than a decade through various ceasefires negotiated from time to time since 1997 but a solution is yet to be found.

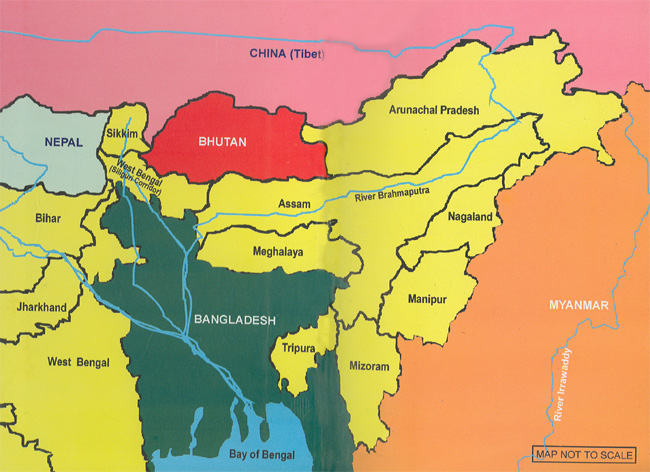

Northeast India covers an area of 255,083 sq. km. It shares 98 per cent of its boundary with four countries. It is connected to the rest of India by 28 km. vide Siliguri Corridor. It comprises seven states which possess a distinct culture, historical traditions and are in different stages of political and economic development. Physiographically, the Northeast comprises three distinct regions – Assam Valley, Purvanchal Region (which includes Nagaland, Tripura, Mizo Hills and Cachar hills and Meghalaya and Mikir Region. The complete area is inhabited by 213 different tribes speaking 325 different dialects.

In an insurgency area, the space is occupied by five actors namely society, insurgents, administration, politicians and security forces. The key to success is to increase the space of the society and reduce that of the insurgents. The six-decade old insurgency in the Northeast continues to endure perhaps on account of failure to manage. Much of what ails the region is the result of a feeling of alienation. The term ‘Northeast’ is not only a physical identity that has been artificially fashioned; but also the one that drives New Delhi’s political, economic and security policies for the region. The policies that New Delhi has been adopting for resolving the insurgency in the Northeast is a mix of military power, suspension of operations, dialogue and ceasefire.

The ULFA insurgency is still active and has also spread to parts of Arunachal Pradesh…

An Overview of Insurgency in the Northeast

When the Constitution was framed, a sub-committee headed by Gopinath Bordoloi was appointed to examine and recommend the constitutional arrangements that would fulfill the aspirations of the tribal population of the Northeast and thus set at rest fears about the possible loss of their unique identity. Recommendations of the Bordoloi Sub-committee were extensively debated and incorporated with some amendments into the Constitution as the Sixth Schedule which protected not only the tribal laws, customs and land rights but also gave sufficient autonomy to the tribes for self-administration with minimum outside interference. However, as events unfolded, hopes were belied. Tribal insurgencies erupted in Nagaland, Mizoram, Manipur, Assam and Tripura at different points in time. The Mizo insurgency was resolved through political settlement. The Naga insurgency, the oldest in the Northeast, has been in a state of suspended animation for over a decade through various ceasefires negotiated from time to time since 1997 but a solution is yet to be found.

The situation in Manipur is probably the worst. The state presents a rather complex picture of ethnic divisions. The Nagas of Manipur hills who feel closer to their kin of Naga hills (in Nagaland) want to be part of Greater Nagaland. Meities, who constitute over 60 per cent of the total population of Manipur, want to maintain their integrity, but the demands are secessionist in nature. They maintain that Manipur was never a part of India and still is not. The ongoing conflict between the Nagas and Kukis further complicates the situation. The level of violence is quite high. The gravity of the situation may be gauged from the fact that recently a Joint Action Committee constituted by the State recommended that civilians be permitted to possess arms to defend themselves against insurgents.

In spite of the 1988 Accord with the Tripura National Volunteer Force, Tripura is also faced with a low level of insurgency and keeps regressing into ethnic violence from time to time. The State is surrounded by Bangladesh except for a small stretch of the border which it shares with Mizoram and Assam. Due to a large influx of illegal immigrants since 1947, the local tribals in the State have been reduced to a minority. The resultant clash of interest between the tribals and the immigrants is the root cause of insurgency in the state. The most worrisome aspect of the insurgency is the process of ethnic cleansing undertaken by the People’s Front of Tripura that has been targeting Bengalis and forcing them to flee the State.

The discontent in Assam has a long history. The partition of India in 1947 started a process by which Assam continued to shrink in size to what it is today. It also resulted in an increased flow of migrants from the erstwhile East Pakistan and from other parts of India. Re-organisation of the rest of the country on a linguistic basis also had its effects on the aspirations of the people of Assam.

The origins of insurgency in Assam can be traced to the Assam Movement started by the All Assam Gana Sangram Parishad (AAGSP) along with the All Assam Students Union (AASU) in 1979. It was an agitation against the so-called “foreigners” and the demographic changes that had occurred due to the large influx of migrants. The Assam Accord of August 1985 which brought the AASU into power, did not bring peace to the state. Encouraged by the success of the violent means adopted by AASU, another militant organisation – the United Liberation Front of Assam (ULFA), started the agitation for “Swadhin Asom” (Independent Assam).

India, like most other democracies is slow to react to developing internal threat…

The ULFA insurgency is still active and has also spread to parts of Arunachal Pradesh. The Bodo area is slowly becoming a flashpoint again, Bodo People’s Progressive Front, now running the Bodo Territorial Autonomous District Council, is in conflict with the secessionist National Democratic Front of Bodoland, which is observing a truce with the Centre since 2005. The 2003 Bodo Accord has not been able to restore peace in the region. Further, illegal migration from Bangladesh threatens to change the demographic profile of Assam and West Bengal which has serious political and security implications for India. Bangladesh however, refuses to accept that any of its nationals are staying outside its boundaries and is also opposed to fencing the Assam–Bangladesh border. The situation is further compounded by the external linkages with Myanmar and Bangladesh, of various insurgent groups operating in the Northeast. There are reports to suggest that terrorist groups located in Bangladesh, are acting in concert with the Inter Services Intelligence (ISI) of Pakistan for spreading terrorism in India.

The Routine Government Response

Since independence, the situation in the Northeast has been quite delicate. The Sixth Schedule of the Constitution was a major step to address the problems that were foreseen at that point of time. However, since then, there has been no coherent strategy to integrate the region into the national mainstream. The Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act, 1958 (AFSPA) was enacted in 1958, essentially to tackle the situation in Nagaland prevailing at that time and was initially supposed to have remained in operation for one year. The Act continues to be in force and extends to all the seven states in the Northeast. Following large-scale protests in Manipur in 2004, a Review Committee was formed by the Government. No final decision has yet been taken and AFSPA continues to be in force.

Every time there has been an agitation or a movement, the response has been to deploy the Security Forces, mainly the Army, to conduct counter insurgency operations, followed by a protracted dialogue and announcement of large financial packages for development. In the absence of effective governance in these states, the funds have often found their way to the insurgent groups who have given up their ideologies and are indulging in large scale extortions. The victims are the transporters, traders, government employees, public and private enterprises and the common man; none is spared. Their aim is to gain power and to control the parallel economy. Insurgency has become an industry and a way of life. In some cases, insurgents have also enjoyed political patronage.

The only insurgency that has been successfully resolved has been that in Mizoram. The two-decade old insurgency (1966-1986) came to an end with the signing of the Peace Treaty on June 30, 1986. It is perhaps time to re-visit this success story to draw lessons which can be applied elsewhere, albeit with modifications.

Recently, a document called “Northeast Vision 2020” prepared at the behest of the Central Government was released by the Prime Minister. Hopefully, it signifies a new beginning for the troubled region but much would depend on its translation into action.

The impression that India is a ‘soft state’ needs to be dispelled by the Government by demonstrating its resolve, politically, diplomatically and militarily…

New Delhi recognises and governs the Northeast despite its non-homogenous character, only as a fused identity. Consequently, the term “Northeast” is not only a physical identity that has been artificially fashioned, but also one that drives New Delhi’s political, economic and security policies for the region. But the diversity that make up the Northeast are apparent. A Nocte of Arunachal Pradesh has as much in common with a Mising of Assam, as would a Kashmiri Pundit have with a Namboodiri from Kerala, despite the fact that in ordinary comprehension, both Nocte and Mising are tribals, just as, in the case of the comparison that is being made, the Kashmiri and Keralite belong to the Brahmin affiliation. It is such indistinct notations that have provided the region with a sense of false homogeneity and – as aforesaid, the character of a “security zone”, the latter perhaps as a result of New Delhi’s policy towards the encircling nations, propelled to a significant degree by circumspection and the need therefore, to create a buffer region.

Reasons for Insurgency in the Northeast

After partition, the Northeastern Areas (Re-organisation) Act, 1971 created three states – Manipur, Tripura and Meghalaya and two Union Territories, Mizoram and Arunachal Pradesh effective from January 21, 1972. The two Union Territories became states in 1987. All the states in the Northeast are in the grip of insurgency or have been through insurgency in the past. The reasons for these are similar and have been enumerated below:

- The roots of insurgency in the area go back to pre-independence days. The tribes were not brought under a strict political control and rigid regulations. The British tribal policy and Christian education are believed to have queered the pitch for Independent India.

- Setting up of reserved forests by British led to the loss of tribal control over natural resources.

- Migration of people from the plains posing economic, cultural and political threat to the tribals.

- Lack of good governance and transparency,

- Faulty nation-building strategies (economic deprivation).

- Inappropriate development.

- Large-scale unemployment.

- Hostile neighbours extending moral and material support.

- Lack of good leadership and popular support.

- Not anti–India but anti-establishment.

- Money for development never reached the target but was diverted to insurgents by politicians to buy security. There was no shortage of recruits as unemployed educated youth were available to join them.

The Gateway Paradigm – A Necessity to End the Insurgency

And so we have, over the past years – with increasing enthusiasm since the early 1990s – the propagation of a new variant of the ‘development solution’:

- South-east Asia begins in Northeast India.

- For India’s Northeast, the future lies in emotional and political integration with the rest of India an economic integration with the rest of Asia.

- India’s ‘Look East Policy’ is meaningless if it does not have an impact on the Northeast region.

The logic derives exclusively from location and history, with almost no consideration of current imperatives of geopolitics, capacities, governance and security. As one commentator notes, “The economic approach to the problems of the Northeast seems based more on historical romanticism than cold economic facts.” In brief, the argument is:

- The Northeast is land-locked and has been further isolated by partition and the existence of a hostile Bangladesh which blocks access to the Indian mainland, except by a tenuous and uneconomical transportation link through the chicken’s neck or the Siliguri Corridor.

- The Northeast is the ‘hub’ or “tri-junction’ of three great civilizations – the Indian, Chinese and Southeast Asian – with a rich history of cultural and trade relations.

- Historically, this tri-junction was at the hub of the famed Silk Route that enriched the enveloping region, including the Northeast. The locational advantages that fuelled the Silk Route still exist and have been infinitely advanced as a result of the new globalisation of the economy and the revolution in transport and communications.

- The region is also joined by and exists as a natural geographical par of multiplicity of regional economic groupings including:

– The South Asia Growth Quadrangle (Nepal, Bhutan, Bangladesh and Eastern/Northeastern India).

– SAARC (South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation).

– ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations).

– Bangladesh, India, Myanmar, Sri Lanka and Thailand in an incipient Bay of Bengal Community (BIMSTEC).

– Greater Mekong Sub-region (GMS) including Myanmar, the Lower Mekong countries of ASEAN, the new China – Yunnan, Myanmar, Laos, Thailand upper – Mekong quadrangle and the New Mekong – Ganga cooperation project.

– The encompassing Indian Ocean Rim – Association for Regional Cooperation (IOR-ARC) and the trans-Himalayan and pan-Asian links being forged by highway, rail and pipeline connections.

- By ‘opening up’ Eastwards, the Northeast would not only secure “wider market access to some of the fastest growing South East Asian and East Asian economies”, but this market integration would also create greater trade between India and these countries, with the Northeast “serving as a gateway”. This trade would then serve as “a driver of rapid economic development of the region”.

- ‘Export led growth’ has been the ‘centerpiece of industrial policy’ in many countries of Asia, resulting in tremendous development in many countries. This is a model that can be replicated in the Northeast.

- Frontier development in the heartland of continents through the development of commercial nodes in border zones along road, rail or inland water corridors creates the potential for the region to become gateways or entry posts.

- The ‘Look East Policy’ envisages the Northeastern region not as the periphery of India, but as the centre of a thriving and integrated economic space linking two dynamic regions with a network of highways, railways, pipelines, transmission lines, criss-crossing the region.

- The Northeast, in addition to its tremendous locational centrality, has immense resource endowments – particularly in bio-diversity, hydro-potential, oil and gas, coal, limestone and forest wealth, and is ideally suited to produce and process a whole range of plantation crops, spices, fruits, vegetable, flowers and herbs.

A great deal of this rhetoric is well intentioned; in other cases, it is simply facile, glib political postures entirely lacking any connect with the realities of the ground. In all cases, however, it reflects either a purely ‘microeconomic’ orientation, with a deliberate neglect of the peculiarities of the political economy of the region or a deceptive superficiality, again with no reference to the situation on the ground. It is crucial to understand:

- You cannot simply order the various components of this supposed strategy off an a la carte menu. Take the idea of the separation of ‘emotional and political integration’ with India, and ‘economic integration’ with South East Asia. In this fractious region, given the patterns of underlying kinship across national borders and the interests of external powers – including both great and lesser powers in the immediate neighbourhood – how precisely is this to be secured in any but an ideal world?

- Various components of the ‘paradigm’ that has been widely articulated and enthusiastically seized upon need to be evaluated within the realities of the prevailing situation, before large amounts of money and political capital are pumped into another doomed project.

- Specifically and immediately, certain unanswered questions arise out of the present concepts of the ‘bridgehead’ or ‘entrepot’ paradigm and these need to be objectively evaluated.

– Market integration can lead to both trade creation – through the emergence of new industries; and trade destruction – as a result of the demise of inefficient operation due to exposure to more efficient competitors from integrating countries, and advantages of economies of scale that may already exist in these.

– The economic transformations that are catalyzed by ‘integration’ may, in fact, bypass the entire traditional sector and replicate the development of ‘colonial’ sectors, such as tea and oil, which have had a long existence in the region – particularly Assam – with little linkage with domestic local commodity, factor and money markets, few forward and backward linkages to the large local economy, and little impact as a driver of growth and general prosperity.

– India’s relations with neighbouring countries are riddled with political and diplomatic minefields. Bangladesh has had a long history of overt and covert hostility. Border disputes and the memory of 1962 place China in the realm of perpetual suspicion. While India’s relations with Myanmar are friendly, but China’s overwhelming presence in Myanmar will, again, create potential difficulties and areas of suspicion. China’s aggressive expansion across South East Asia and in the Indian neighbourhood is also perceived as a significant threat – both in economic and security terms. Given the existing political relationships in the neighborhood, the actual realisation of trade potential is constrained.

– Most significant, however, is the fact that manufactured goods of local origin comprise little of the existing (formal and informal) trade with the Northeast’s neighbours. While bicycle exports to Bangladesh were thriving, the only bicycle factory in the region, at Guwahati, was shut down, and export requirements were met from elsewhere despite high transport costs. Existing trade, though substantial in local terms, has resulted in nothing more than the emergence of a few trading centres near the borders.

– The capital cost of ‘integration’ and realisation of the Northeast’s potential does not appear to have been realistically factored into the benign projections currently in favour. A few examples are:

(i) `228,000 crore at 2002-2003 prices for full development of hydropower potential.

(ii) The Stillwell Road project is now conceptualised as part of the Trans Asia Express Way and the Trans Asian Railway that could link Southwest Chinese trading centres and the entire South East Asian region. India’s trade with China would then need to cover less than 2,000 km, as against the current 6,000 km trip through the Strait of Malacca. The cost implications would be staggering.

(iii) `93,619 crore at 1996-1997 prices for infrastructure development within India. (High Level Commission to be Prime Minister on Tackling Backlogs in Basic Minimum Services and Infrastructure).

(iv) Current sea transport accounts for as little as five per cent of the landed cost of any commodity – consequently, geographical proximity has little to do with trade, except in limited border trade. It is not clear that the massive investments required for developing the Trans-Asian Road and Rail Links will be forthcoming in any rational economic policy framework, as against ‘historical romanticism’.

– Resource endowment and location themselves are not enough to unleash a dynamic process of economic development or productive integration. The ‘potential’ of the Northeast has always existed – but it has not been realised, and there are overwhelming reasons in the political economy of the region why this is the case.

Politico – Military Synergy – Necessary Steps

In any society, especially which is in turmoil, the ‘Centre of Gravity’ are the people. The focus, therefore, must be on them – their perceptions, aspirations, sense of isolation, deprivation, alienation or grievances that need to be addressed. Regrettably, while seeking solutions to these complex problems we tend to ignore them and only consider issues put forth by the insurgents. To be able to achieve resolution of the problem, the state has to function in a transparent, non-partisan and credible manner. To that extent, a rejuvenated, conscientious, dedicated and competent bureaucracy has to be in place to ensure effective administration, which is unfortunately lacking in most of the states in the region, due to a variety of reasons.

The manner in which events over the past decade have been handled by the Centre have only strengthened the perception of adversaries that India is ‘soft’ state.

The problem in the Northeast is complex and has various dimensions – ethnic, cultural socio-economic and security. It is thus axiomatic that the solution cannot be found by one particular ministry at the Centre. The Development of the North-Eastern Region (DONER) Ministry is constituted for and focused on development in the Northeast region, Development does address some of the aspects stated above, but does not deal with security issues. The Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) deals with security matters and forces deployed for Counter Insurgency (CI) operations in Assam, Nagaland, Manipur ALO and Tripura. There is thus a definite disconnect in perceptions and comprehension of the situation at the Centre between the ‘decision makers’ (MHA) and the executors (Army formations deployed in various states). The Army HQ functions through the MOD, however the latter is only on ‘listening watch’ as ‘internal security’ is the preserve of the MHA! The harsh truth is that there is hardly any ‘Politico-Military Synergy’ at the Centre.

Consequently, a similar lacuna exists at the state level where the Army is considered to be for “Aid to Civil Authority” and not a part of the ‘Decision Making Process’. If synergy is to be achieved, there has to be a change in the mindset of the ‘Politico Bureaucratic’ hierarchy, to allow the army to be a part of the organisation. This can only happen if the political leadership asserts itself and interacts with senior military officers directly sans the bureaucracy. To ensure implementation, this change must be effected at the Centre and only then will it percolate downwards. Till this systemic change is brought about, whatever synergy is being achieved at the Centre or the states is purely ‘personality oriented’ and contingent upon the ‘personal vibes’ between heads of various organisations – certainly not the best way to achieve synergy.

It is an accepted fact that there is no military solution to insurgency, but the military is an essential ingredient in the effort seeking a solution. Political consolidation must follow the success achieved by military operations against insurgents. It thus emerges that politico–military synergy is the sine quo non for a solution. Some aspects wherein synergy is mandatory to ensure that the CI efforts shall succeed are covered in succeeding paragraphs.

Establishment of Central Expert Security Group

India, like most other democracies is slow to react to developing internal threat. Weak resolve, political pressures, bureaucratic hurdles and the lack of inter-agency integration as well as cooperation, prevent the formulation of a clear aim, overall policy and plan. Besides, lack of in-depth knowledge at the Centre of the Northeast states afflicted with insurgency, has led to these problems being treated in a routine manner or merely as just another more issue. Mired in the routine, those dealing with it in the Ministry cannot visualise feasible solutions to the complex problems of the region; well-thought out measures or responses, are exceptions.

With reasonably large number of officers available from the Army, Police, Para Military Forces (PMF), bureaucracy and academia who have grassroots knowledge, a selected expert group needs to be set up by the Centre to evolve policy(s), so as to achieve conflict resolution. Retired personnel, if any, can be appointed on a contractual basis. This group must be empowered to take decisions and direct measures to be taken. It must not be an adjunct of the Northeast desk of MHA. It should be under a separate minister for the Northeast or perhaps be an adjunct of the DONER Ministry. Though this group would be a part of the Central Government, it should be located within the Northeast region.

In response to a possible argument that the National Security Advisory Board (NSAB) already exists for the purpose, it needs to be stated that the NSAB has a vast canvas to cover and its members may not have requisite knowledge of the Northeast region. Besides, the NSAB is only an advisory body and has no executive powers, whereas the expert group being recommended will be able to address issues specific to the Northeast and facilitate resolution of problems.

Establishing “Unified Command”

After protracted efforts by the Army, the concept of ‘Unified Command’ has been accepted and set up to tackle insurgency in Assam and Manipur. The set-up in Assam called the ‘Strategic Group’, is headed by the Chief Secretary and functions under the state bureaucracy in violation of the concept. Bereft of political involvement and direction, the organisation suffers from bureaucratic hassles and inefficiency. The ‘Operational Group’ is headed by General Officer Commanding (GOC) 4 Corps.

In Manipur, the ‘Combined Headquarters’ has the Chief Minister as the Chairman whereas the ‘Strategic and Operational Group’ is headed by the Chief Secretary; the principle of operational control by the lead agency to synergise operations, has been ignored thus negating the intended benefits of the concept. Besides, functionally, the Chief Minister has delegated authority to the Chief Secretary with its concomitant fall-outs. Until and unless the state-level political leadership gets actively involved and oversees the functioning, ‘Unified Command’ will continue to remain a mere concept and not achieve its stated objectives.

Synergy Between Various Intelligence Organisations

The lack of synergy between the Army and various civil organisations in the conduct of CI operations is the most glaring weakness in the realm of intelligence. Lack of coordination and cooperation has come about, as each agency tends to pursue its own agenda by withholding information and indulging in ‘one-upmanship’, at times even at the cost of larger gains. Though the Unified Command has an ‘intelligence group’ as part of its organisation, the functioning is well below the desired standard. In the states without Unified Command, intelligence sharing is virtually non-existent.

Another major weakness in the process of acquiring, collating, analysing and disseminating intelligence information is the assessment, which is more generic than specific, to ensure a safe fall-back position for the authors of the intelligence. Total synergy amongst various intelligence agencies, be it civil or military, is the only way actionable intelligence can be provided to seriously impair operational capabilities of insurgent groups. Such a change can only come about if the political leadership allows these agencies to perform their primary tasks unhindered and instead provides positive directions for implementation of CI measures.

Information Warfare

In this age of ‘information explosion’, the insurgent groups are techno-savvy and use all available means to spread disinformation, propaganda, unleash psychological warfare to demoralise the state apparatus and create a feeling of despondency in the public. The Army has been making efforts to counter such propaganda to negate efforts of the insurgents. Regrettably, these are not being supported by the state apparatus viz., the publicity department or the Press Information Offices. These organisations can bridge gaps in language, dialects, cultural and social aspects.

Besides, a synergised public information and counter propaganda initiative aimed at the common man is necessary. In this effort, the state machinery has an important role to play. Unfortunately, this segment of the state government apparatus is only utilised for collecting data for publishing in the Annual Reports of achievements of the state government and may be some routine brochure/pamphlets and does not contribute to the CI effort. There is a requirement of setting up a Psychological Operations Cell by the state government in concert with the local Army formation. A synergised effort in this regard will be a force multiplier for the CI effort and pay handsome dividends, since the common man does not have access to information except that put out by the vernacular media, which is a mouthpiece of the insurgent groups.

Development Projects

As highlighted earlier, only an insignificant amount of financial largesse given by the Centre is actually utilised for development due to corruption. Besides, there is no audit or accountability of the expenditure by the state government of funds provided by the Centre for specific development projects. As no benefits of the development projects reach the masses, it leads to a feeling of neglect and further alienation. The states invariably misrepresent facts and blame the Centre for the lack of development. In some cases, the state administration may not be able to reach out to projects in far-flung areas to ensure smooth execution and monitor progress. Politico-military cooperation can certainly provide an avenue to ensure successful completion of such projects as Army units/sub-units are located almost everywhere and can certainly help in monitoring progress and providing accurate feedback. This is only feasible if details of all such projects are shared with the Army; a step which the state authorities are loath to take. A joint approach in this regard will not only accelerate development per se with its concomitant spin-offs but will also assuage the feelings of the masses to some extent.

Institutionalised Mechanism to Obtain Inputs

Over a period of time, it has been observed that whenever required, the MHA summons the Chief Secretary and the Director General Police of the concerned state to obtain inputs on various current issues or incidents. However, no direct inputs are taken from the Army in the state, even if the incident involves them. It must be appreciated that the Army is as much involved in tackling the problem and in fact has primacy in the conduct of operations. There is thus the necessity of evolving an institutionalised system of obtaining inputs from the Army as well. This would imply that if and when the Centre requires an update or inputs related to an ongoing issue or incident in an insurgency environment, the Army Officer at the helm of affairs in the State would also be part of team.

To those skeptical of this setting a wrong precedent, it merits mention that an arrangement already exists wherein IGAR (N), who is the Major General in-charge of all troops deployed in Nagaland, attends talks between the Government and the NSCN (IM) at Delhi, with the ADGMO (A), Army HQ also present. A similar system can thus be institutionalised wherever required. Besides giving definite impetus to politico-military synergy, it will enable inputs to the authorities at the Centre and facilitate decision making.

Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA)

When under pressure due to operations by security forces, the insurgents and their sympathisers invariably raise the bogey of Human Rights (HR) violations and seek abrogation of the so called ‘draconian’ AFSPA. It merits mention that the AFSPA can only be imposed after the state government has promulgated the Disturbed Area Act (DAA) in whole or part of the state. This provision is reviewed every six months. In case the state or Central Government does not promulgate the DAA, the AFSPA becomes inoperative. Seven constituencies of Imphal town are outside the ambit of the DAA and consequently, the AFSPA since August 2004.

Notwithstanding the above, it is imperative to have legal provisions to provide protection to the troops conducting CI operations, be it in the form of AFSPA or Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act 1967, suitably amended or any other legal provision. Without such provisions, troops will not be able to undertake any operations against insurgents, but will only be on the defensive and reactive, which is operationally unacceptable. Needless to state that those found guilty of HR violations must be dealt with in a transparent manner and speedily.

Imposition of the AFSPA is a political decision. However, politicians of the concerned state continue to find the AFSPA a handy tool to beat the SF publicly. Paradoxically, in private, they state that it should not be revoked. With divergent views emerging from various organs of the state, insurgents exploit the AFSPA issue through the media; the security forces have to bear the flak, even in case of false allegation. No support is ever forthcoming to the Army from the state polity. Instead politicians of the ruling party also are known to exploit even false incidents to score brownie points. If there is politico-military synergy on this issue, unwarranted conflagrations can be averted and false propaganda by insurgents and their sympathisers negated.

Government’s Stance: Position of Strength

The manner in which events over the past decade have been handled by the Centre, be it the hijack of IC 814, the killing of BSF personnel by Bangladesh Rifles or response to the Chinese aggressive diplomatic posturing or others, have only strengthened the perception of adversaries that India is ‘soft’ state. The Government did not even take a well-considered stand on the issue of ‘Nagalim’ initially and have been vacillating thereafter, causing periodic turbulence in Manipur.

The impression that India is a ‘soft state’ needs to be dispelled by the Government by demonstrating its resolve, politically, diplomatically and militarily. The Government must deal with the insurgents from a position of strength. To this end, India must have a clear stance on sanctuary and support to the insurgent groups by neighbouring countries and must retain the option of an armed response besides coercive diplomacy. Setting up of an expert group as suggested, will also be an indication of the nation’s resolve to deal with the situation in the Northeast and positive indicators of achieving politico-military synergy.

Illegal Immigration

Immigration of large numbers illegally from Bangladesh into Assam, Tripura and West Bengal, has resulted in a demographic inversion in the border districts of these states. A fall-out of this has been sprouting of madrassas and illegal settlements in the vicinity of the border with their concomitant security implications. This potential security threat is regrettably being ignored for short-term political gains. If not tackled with urgency, this is a handy tool for elements inimical to India to exploit for destabilisation of the region and eventually for balkanisation of the country. Besides revamping the immigration set up at the border, there is a need to examine the issue of work permits and enabling legal provisions need to be promulgated to deal with this menace. Politico–military synergy on this issue is indispensible to eradicate insurgency in the Northeast.

Countering Foreign Elements

Support to insurgent groups including setting up of camps in Myanmar and Bangladesh, is an incontrovertible fact of involvement of foreign elements. Despite intensified diplomatic efforts, there has been no change in the situation on the ground. This is another area where politico-military synergy is vital. Governments in both these countries are being controlled by the Military. It would thus be prudent to allow the Indian Army to increase interaction with the military of Bangladesh, Myanmar and the PLA, in addition to the renewed diplomatic efforts. In case of persistent denials and in view of their aggressive behavior with BSF in the past, India must exhibit resolve by launching precision strikes by Special Forces on camps of IIGs in Bangladesh. .

There are a number of other issues such as revamping and rejuvenating the state bureaucracy and administration; strengthening, modernising and training of the state police force(s) to tackle insurgents, accountability of the state developmental institutions and others.

Conclusion

Mired in appalling under-development, with the rise of ‘underground’ economy comprising smuggling, extortion, fake currency, arms smuggling, drug trafficking, the Northeast finds itself trapped in its economic backwardness. Insurgent groups have also shed the veil of ideology and are indulging in criminal activities. It is high time the local politicians also accept responsibility and develop a stake in the development in their states, rather their own and resist from continuously pointing a finger for all their ‘ills’ at New Delhi.

The importance of Northeast must not be ignored because the region is highly susceptible to external influences and its destabilisation can lead to the balkanisation of the country. In order to achieve conflict resolution, political consensus across party lines is essential so as to formulate a cogent and implementable strategy. As on today, at the executive end, all organs of the respective states are engaged in pursuing their own agenda at the cost of the national aim. The main shortcomings are lack of cooperation, coordination and synergy amongst major organs of the state dealing with the problem.

The underlying issue is absence of faith in the Army by the political leadership and the bureaucracy due to vested interests of the latter. Till the government does not share their perceptions related to security issues at the apex level with the hierarchy of the armed forces, signaling a change in their attitude towards them, the Army regrettably will not be able to deliver and not because of inability but because of the denial of opportunity to do so. It is therefore, my earnest appeal to the powers that be that if ‘Conflict Resolution’ in the Northeast is the desired end state, let the Army be a party to arriving at a solution and not use it merely as in ‘aid to civil authority’ mode of yesteryears.

It must be realised that the North Eastern Region is India’s near abroad – both in physical and mental aspects. India’s policy seems to be to internalise the issue and to seek political accommodation for it rather than to have a strategic construct. As a result, we have failed to realise the impact of peripheral states on politics, economics, demographics and security. Our ‘Look East’ policy needs to actually start from our Northeast.