The Border in 1947

As provided in the above-mentioned account, historically, the Chinese boundaries ended along the Kun Lun Range and China did not exercise any jurisdiction south of these mountains. The Chinese had begun to move into areas south of the Kun Lun in the Raskam Valley only as a result of the British policy in the closing decades of the 19th century. However, China had no justifiable claim to, or presence in, the Shaksgam Valley, south of the Aghil Range.

Yet, under the so-called boundary agreement with Pakistan of March 02, 1963, China took for itself not only Raskam but also the entire Shaksgam area in return for relinquishing its specious claim over Hunza.

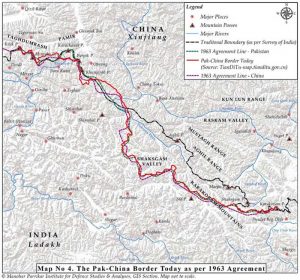

As late as 1938-39, the Government of India had once more reasserted its position on the Shaksgam area, after the Mir of Hunza had been advised in 1936 to cease the exchange of gifts with the Chinese and relinquish his rights over Raskam. Hence, in 1947, independent India inherited a boundary which included as Indian territory Hunza as well as the trans-Karakoram tract in Shaksgam, running along the Mustagh-Aghil-Qara Tagh-Kun Lun ranges. This line was compromised by Pakistan in its ‘agreement’ with the Chinese in 1963. By giving in to the Chinese claim to a boundary along the Karakoram Range, Pakistan not only compromised India’s position along the Kun Lun Range to the north-west of Karakoram Pass but, in effect, also gave the Chinese a chance to deny Kun Lun as India’s boundary with China east of the Karakoram Pass and to claim that it ran, instead, along the Karakoram Range. As such, China’s claims in the trans-Karakoram tracts to the west of the Karakoram Pass had absolutely nothing to do with its position to the east of the Pass since it had no historical presence at all in the area of Aksai Chin.

Post-Colonial Phase: The Sino-Pak Deal

From the events that led to the 1963 agreement between China and Pakistan, it is clear that China started asserting its territorial claims on the frontiers of the Jammu & Kashmir State in the late 1950s. On January 23, 1959, Chinese Premier Zhou En-Lai advanced such claims through his letter to then Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru.25 From 1953, Chinese troops had started entering into territories in eastern Hunza. In October 1959, Pakistani media reported illegal intrusion of Chinese troops into these lands claimed by the Mir of Hunza. The troops rustled some livestock from there, prompting the then foreign minister of Pakistan to react sharply stating that Pakistan would defend its frontiers by all possible means. In the late 1950s, with relations between India and China undergoing a sharp deterioration, Pakistan’s then President Ayub Khan sensed an opportunity to appease China in order to externally balance souring relations with India. In the face of the Chinese ingress into the Hunza Valley, he chose to open a line of communication with Beijing to discuss the border issue.

At one point there were reports of assurances from Zhou En-Lai on March 16, 1956 that the people of Kashmir had already expressed their will,26 and later on July 16, 1961, that China had never stated in any document that Kashmir was not a part of India,27 thus leaving its position on Kashmir very ambiguous. This may have put further pressure on Ayub Khan to intensify his efforts to secure the Chinese goodwill. The failure of the India-China border talks during June-December 1960, the changed security situation in the region following the India-China war of 1962, as well as indications of Western military support for India, may have been instrumental factors in bringing China and Pakistan together.

Dismayed by the American show of support for India, Pakistan castigated Western military aid as an ‘unfriendly’ and ‘hostile’ act and succeeded in putting enough emotive pressure on the United States (US) to persuade India for a dialogue with Pakistan on Kashmir, resulting in six rounds of talks at the level of Foreign Ministers Zulfikar Ali Bhutto and Swaran Singh (December 1962-May 1963), which ended in failure, primarily because of the fact of the Pakistan-China border agreement of March 02, 1963. The US State Department believed that the 1963 agreement “destroyed the slim prospects” of the talks, and the British foreign ministry called its timing “unfortunate”.

Over the two years of negotiations, Pakistan came out with unconvincing and self-serving logic to systematically downgrade the historical claims of the Mir of Hunza in order to pave the way for conceding the territory in question to China. In May 1960, Pakistan revealed that it had decided to negotiate the border issue with China. On January 15, 1961, the Pakistan Foreign Minister revealed to the media that China had agreed in principle to demarcate its boundary with Pakistan and that talks in this regard were in progress. By the end of May 1961, the essential contours of the agreement started taking shape, even as Beijing mendaciously kept assuring India that China had not discussed anything with Pakistan until then.

Maps with maximalist claims were exchanged between the two sides in early 1962. Ironically, the map produced by the Survey of Pakistan, which showed the Shaksgam Valley and parts of Xinjiang within POK, was later disowned by the Pakistani leadership who held that the concerned institution had no authority to draw the line of an undefined border on the map! It was equally interesting that the Chinese withdrew their map after Pakistan agreed to concede more strategic territories in the trans-Karakoram tract than had earlier been claimed by the Chinese. The benefits to Pakistan flowed immediately thereafter. By May 1962, China had decided to take a position on Kashmir that was much closer to that of Pakistan. On May 31, 1962, for the first time, the Indian Embassy in Beijing was informed through a ‘Note’ that China had never accepted “without reservation” the position that Kashmir was under Indian sovereignty.28

According to the ‘pamphlet’ titled “Sino-Pakistan ‘Agreement’ March 2, 1963; Some Facts”, released by the Government of India on March 16, 1963, traditionally, the boundary to the west of the Karakoram Pass ran along the watershed, dividing the tributaries of the Yarkand and Hunza rivers, and connecting the various passes from the west to the east, i.e., Kilik, Mintaka, Karchanai, Parpik and Khunjerab. From Khunjerab, it crossed the Shaksgam River and ran along the Aghil mountains, across the Aghil, Marpo, the Shaksgam and Karakoram passes till the Kun Lun Range.

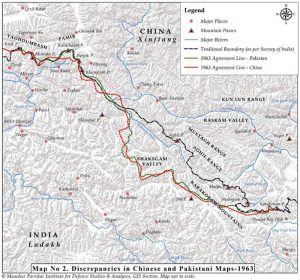

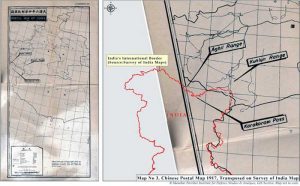

The 1917 postal map of China29 (re-printed by the Chinese Government in 1919 and 1933; see Map 2) showed the southern boundary of Xinjiang at the Aghil and Kun Lun ranges. A 1762 map of Xinjiang also showed its southern frontier extending only up to the Kun Lun Range. However, these facts were overlooked in the egregious bargain struck by Pakistan to give away the Shaksgam Valley east of Hunza to China on a platter.

Pakistan’s Illegal Concessions to China – A Subterfuge

Pakistani concessions to China were largely kept away from the public eye in Pakistan. The negative press, such as there was in Pakistan, was conveniently brushed aside. It was also forgotten that the phrase used in the joint communique of May 1962, i.e., “the area, the defence of which is the responsibility of Pakistan”, was suitably altered in the agreement of March 02, 1963 as an area covering “contiguous areas, the defence of which is under the actual control of Pakistan”, in order to cloak Pakistan’s disproportionate concessions to China.

The fact that there were discrepancies [See Map 3] even in the maps circulated by the two countries depicting this border following the agreement was pointed out in the Indian ‘pamphlet’ cited above. Of course, these discrepancies have been resolved now [See Map 4], but the falsity of the Pakistani assertion can be clearly noticed in these maps.

Ignoring all this, Bhutto thundered in the UNSC on March 26, 1963 and also later in the Pakistan National Assembly on July 17, 1963 that Pakistan had gained some 750 square miles (1,942 sq kms) of land, including the Oprang Valley and the Darband-Darwaza pocket along with its salt mines, as well as access to all passes along the Karakoram Range and control of two-thirds (later three-fourths) of the K-2 mountain including the summit. In reality, historically speaking, China had no claims to the K-2 mountain. In explaining the deal, Bhutto went on to state:

It is a matter of the greatest importance that through this agreement we have removed any possibility of friction on our only common border with the People’s Republic of China. We have eliminated what might well have become a source of misunderstanding and of future troubles…An attack by India on Pakistan would no longer confine the stakes to the independence and territorial integrity of Pakistan. An attack by India on Pakistan would also involve the security and territorial integrity of the largest state in Asia.30

Most leaders in Pakistan, including Ghulam Abbas, the leader of All Jammu and Kashmir Muslim Conference, hailed the agreement. Abbas even called China, “a dependable friend and ally” and “whose friendship could be of great value in liberating Kashmir from India”.31 The entire negotiation process was witness to the tame surrender by the Pakistan leadershipto Chinese bullying and, perhaps, also a Faustian bargain for buying Chinese goodwill as a reliable and steadfast ally against India.

The China-Pakistan collusion was clearly evident in the process and China became a direct party to the Kashmir issue both by concluding the 1963 agreement with Pakistan and taking the trans-Karakoram tract and, earlier, by occupying Aksai Chin. Article VI of the 1963 border agreement unambiguously mentions that:

….after the settlement of the Kashmir dispute between Pakistan and India, the sovereign authority concerned will reopen negotiations with the Government of the People’s Republic of China on the boundary as described in Article Two of the present agreement [defining the border alignment], so as to sign a formal boundary treaty to replace the present agreement, provided that in the event of the sovereign authority being Pakistan, the provisions of the present agreement and of the aforesaid protocol shall be maintained in the formal boundary treaty to be signed between the People’s Republic of China and the Islamic Republic of Pakistan.

India’s contention was, and is, that Pakistan did not have the sovereign authority to enter into a territorial agreement with China given India’s legal claim to the State of Jammu & Kashmir.

Under international law, the right of entering into treaties and agreements is an attribute of sovereignty. Furthermore, a sovereign cannot presume to exercise sovereign functions in respect of territory other than its own. Having regard to the UN resolutions of January 17, 1948; August 13, 1948; and January 5, 1949 (UNCIP Resolutions), it is clear that Pakistan cannot (and does not) claim to exercise sovereignty in respect of Jammu & Kashmir.32

Interestingly, quoting Article VI of the 1963 agreement, Bhutto had said in the UNSC:

….Article 6 of the Sino-Pakistan Boundary Agreement makes it clear that the Agreement is of a provisional nature between Pakistan and China, and that after the settlement of the Kashmir dispute, the sovereign authority that will emerge in Jammu and Kashmir, will reopen negotiations with the Government of the People’s Republic of China, so as to sign a formal boundary treaty to replace the present Agreement.33

He also stated that this was in conformity with the stand of the Government of Pakistan in the letter of 3 December 1959, to the UNSC in the context of the Sino-Indian dispute over the boundary of Ladakh, which said:

….my Government is bound by its duty to declare before the Security Council that, pending determination of the future of Kashmir through the will of the people impartially ascertained, no position taken or adjustments made by either of the parties to the present controversy between India and China or any similar controversy in the future shall be valid or affect the status of the territory of Jammu and Kashmir.34

China’s actions in occupying Aksai Chin, and subsequently, in usurping the Shaksgam tract in 1963, did have a direct bearing on the territory of Jammu & Kashmir. Given that China had become a party to the territorial dispute in Jammu & Kashmir, it was naturally inclined towards settlement of the issue in favour of Pakistan, in order to preserve its territorial gains from the 1963 agreement.

On the basis of this agreement, China has carefully nurtured Pakistan as a quasi-colony over the years. As Chinese power grew and that of Pakistan withered because of its self-defeating foreign and security policies, China found it easy to manipulate Pakistani leaders at will to strengthen its control over Pakistan. The Karakoram Highway and the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) both use this contested frontier to bring the two countries together in a closer embrace and help China build an alternative lifeline to the Arabian Sea. India has consistently registered its protest at the route of the so-called economic corridor which traverses through terrain that legitimately belongs to India.

Conclusion

Unfortunately, China’s entanglement in the Kashmir issue has not received adequate attention of the strategic analysts and commentators, both in India and externally. China has had a free run so far and feels comfortable raising the issue precisely because its own status as an occupier of territory in Jammu & Kashmir has not been adequately publicised.

That China is an interested party to the dispute and has played an opportunistic historical role in adding to the complexity of the issue is a fact which should be brought to light in scholarly writings as well as in statements at the UN or any other international fora whenever the occasion presents itself in response to Pakistan raking up the issue of Jammu & Kashmir, singly or in tandem with China. This would be consistent with India’s position on Jammu & Kashmir in terms of its cartographic depictions as well as statements and resolutions in the Parliament over the years.

Notes:

1.Official Twitter Account of the Office of Shri Amit Shah, Union Home Minister, Twitter Post, August 06, 2019, 3:05 PM. Also see “When I talk about J&K, PoK, Aksai Chin are included in it: Amit Shah in Lok Sabha”, The Indian Express, August 06, 2019.

2.“Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Hua Chunying’s Remarks on the Current Situation in Jammu Kashmir”, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, August 06, 2019.

3.“India’s Right of Reply”, 75th Session of the United Nations General Assembly, Permanent Mission of India to the UN, September 25, 2020.

4.“Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Zhao Lijian’s Regular Press Conference on October 13, 2020”, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, October 13, 2020.

5.“Transcript of Virtual Weekly Media Briefing by the Official Spokesperson (15 October 2020)”, Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, October 16, 2020.

6.The discussion in this section is based on a detailed historical account provided by Gondker Narayana Rao, who served as an Advisor to the Indian delegation which discussed the border question with the Chinese officials in Beijing, New Delhi, and Yangon in 1960, in his book The India-China Border: A Reappraisal, Asia Publishing House, Delhi, 1968, pp. 41-60.

7.G. J. Alder, British India’s Northern Frontier, 1865-95: A Study in Imperial Policy, Royal Commonwealth Society, Longmans, London, 1963, p. 1.

8.See Gondker Narayana Rao, n. 6, p. 42.

9.William Moorcroft (1767-1825), an Englishman, a veterinarian and explorer, employed by the East India Company, travelled extensively throughout the Himalayas, Tibet and Central Asia. He stayed in Leh in 1820-22. His book is an important source of information for historians and geographers. See William Moorcroft and George Trebeck, Travels in the Himalayan Provinces of Hindustan and the Panjab; in Ladakh and Kashmir; in Peshawar, Kabul, Kunduz, and Bokhara, 1819-1825, Prepared for the Press, from Original Journals and Correspondence, by Horace Hayman Wilson, Vol. I, Published under the Authority of the Asiatic Society of Calcutta, John Murray, London, 1841.

10.Ney Elias (1844-1897) was an explorer, geographer, and a diplomat, most known for his extensive travels in the Karakoram, Hindu Kush, Pamirs, and Turkestan regions of High Asia and for providing strategic information to the British on frontier politics. His accounts are available in the Indian National Archives.

11.Francis E. Younghusband (1863-1942) was a British Army officer and explorer. He is known for his travels in Kashmir, the Far East and Central Asia. He led the 1904 British expedition to Tibet. He held official positions including British Commissioner to Tibet and President of the Royal Geographical Society. See his book Report of a Mission to the Northern Frontier of Kashmir in 1889, Printed by the Superintendent of Government Printing, Calcutta, India, 1890 [Available at Foreign Office Library, London].

12.See Gondker Narayana Rao, n. 6, p. 44.

13.Ibid., pp. 48-49.

14.Ibid., p. 46.

15.For a detailed account, see Parshotam Mehra, An ‘Agreed’ Frontier: Ladakh and India’s Northernmost Borders, 1846-1947, Oxford University Press, Delhi, 1992, pp. 70-71.

16.That the Russians were quietly instigating China, “by threat or otherwise”, to retain its hold over Hunza, was not unknown to the British. A mention of Macartney’s note to India, dated December 19, 1891, is made in Parshotam Mehra’s book. Ibid. p. 73.

17.Quoted in Gondker Narayana Rao, n. 6, p. 49.

18.George Macartney (1867-1945) was half-Chinese and served the British Indian Government as Consul General to Kashgar (1908-1918). He was first sent as ‘Special Assistant for Chinese Affairs to the British Resident in Kashmir’ in 1890. In fact, he helped Younghusband as an interpreter. The Chinese were suspicious of his posting and accepted him as a Consul only in 1908. He played a role in developing a ‘Line’ which was proposed by the British to China as the boundary in the Aksai Chin area in 1899, via its envoy to China, Sir Claude MacDonald. The line came to be known as the Macartney-MacDonald Line.

19.Major General John Charles Ardagh (1840-1907) was an Anglo-Irish officer of the British Army. He served in different capacities as a military engineer, surveyor, intelligence officer, and a colonial administrator. Along with William Johnson (d. 1883), British surveyor in the Great Trigonometric Survey of India and later Governor of Ladakh, he developed a line that was proposed as a boundary between Xinjiang and Tibet along the crest of the Kun Lun Mountains north of the Yarkand River. This was not acceptable to the Chinese.

20.See Parshotam Mehra, n. 15, p. 74.

21.In 1899, Claude Maxwell MacDonald (1852-1915), a British soldier and diplomat and Her Majesty’s Minister in China (1896-98), authored a diplomatic note with George Macartney, the British Consul General in Xinjiang (1908-1918), which proposed a new delineation of the border between China and British India in the Karakoram and Aksai Chin areas, known as the Macartney–MacDonald Line, which was not formally accepted by China.

22.Adelbert Cecil Talbot (1845-1920) served in the British army and civil service during 1867-1900. He joined the Indian Political Service in 1873 and served as Resident in Kashmir during 1896-1900.

23.Vincent Arthur Henry McMahon was a British Indian Army officer and a diplomat. He also served as an administrator in British India and worked as a Political Agent in Gilgit and later as Commissioner of Balochistan (1909-1911). When McMahon was the Political Agent of Gilgit, he wrote a report titled “Hunza’s Relations with China”, wherein he stated that “Hunza’s vassalage to both China and Kashmir was purely nominal”.

24.A. G. Noorani, India-China Boundary Problem, 1846-1947: History and Diplomacy, Oxford University Press, New Delhi, 2011.

25.Chinese Premier Zhou En-Lai wrote: “I wish to point out that the Sino-Indian boundary has never been formally delimitated. …there are certain differences between the two sides over the border question…The latest case concern[s] an area in the southern part of China’s Sinkiang Uighur Autonomous Region, which has always been under Chinese jurisdiction…And the Sinkiang –Tibet highway built by our country in 1956 runs through that area. Yet recently the Indian Government claimed that that area was Indian territory. All this shows that border disputes do exist between China and India.” For full-length citation, see “Letter from the Prime Minister of China to the Prime Minister of India, 23 January 1959”, in Notes, Memoranda and letters Exchanged and Agreements signed between The Governments of India and China 1954 –1959, White Paper I, Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India.

26.Indian Ambassador R. K. Nehru had a meeting with Chinese Prime Minister Zhou En-Lai and the Vice Foreign Minister Chang Han-fu on March 15, 1956, following which he wrote this note, wherein he mentioned that Premier Zhou felt that “the US had no reason to intervene in the Kashmir question. Moreover, Kashmir people had already expressed their will”. He went on to tell the Ambassador that he would tell the Pakistani Premier when he would visit Peking that “it was most unwise to include Kashmir question in the [US-Pak] Karachi Communique and that it was a method destined to be defeated”. See “Karachi Communique and Indo-Pak Relations”, in Avtar Singh Bhasin (ed.), India-China Relations 1947-2000: A Documentary Study, Vol. II, Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, Geetika Publishers, New Delhi, 2018, p.1594.

27.In his talks with the Secretary General of the Indian Ministry of External Affairs on March 16, 1956, Premier Zhou asked: “Can you cite any document to show that we have ever said that Kashmir is not a part of India?” He also said that Pakistan had proposed border talks but the Chinese Government had “not discussed with them anything so far”. See “Sino-Pakistan ‘Agreement’ March 2, 1963, Some Facts”, External Publicity Division, Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, March 16, 1963, p. 15.

28.In the “Note”, the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs makes the following assertion: “The Indian note alleges that the Chinese Government accepted without reservation the position that Kashmir was under Indian sovereignty, that there is no common boundary between China and Pakistan, and that therefore, China has no right to conduct boundary negotiations with Pakistan. This allegation is untenable. When did the Chinese government accept without any reservation the position that Kashmir is under Indian sovereignty?…This is not only a unilateral misrepresentation of facts but a delusion imposed on others.” See “Note given by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Peking, to the Embassy of India in China, 31 May 1962”, in Avtar Singh Bhasin (ed.), India China Relations 1947-2000: A Documentary Study,Vol. IV, Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, Geetika Publishers, New Delhi, 2018, p.3691.

29.See Appendix XII in “Sino-Pakistan ‘Agreement’ March 2, 1963, Some Facts”, External Publicity Division, Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, March 16, 1963.

30.Z. A. Bhutto, Foreign Policy of Pakistan: A Compendium of Speeches Made in the National Assembly of Pakistan, 1962-64, Pakistan Institute of International Affairs, Karachi, 1964. Also see “Address to National Assembly on Reappraisal of Foreign Policy — Western Arms for India — Negotiations with India on Kashmir—Boundary Agreement with China July 17th 1963”, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto Speeches from 1948–1965.

31.Cited in Manzoor Khan Afridi and Abdul Zahoor Khan, “Pak-China Boundary Agreement: Factors and Indian Reactions”, International Journal of Social Science Studies, 4 (2), February 2016, p. 3.

32.Cited by Claude Arpi, “The Truth About Ladakh’s Shaksgam: Correcting Historical Wrongs in J&K”, Deccan Chronicle, November 18, 2019.

33.For Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s speech at the UNSC on March 26, 1963, see “The Sino-Pakistan Boundary Agreement March 26, 1963”, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto Speeches from 1948–1965.

34.Ibid.

Interesting, informative detailed article on this critical issue of Chinese lust for the expansionism since ages. Lackluster approach by British on the issue, then ruling over India is now costing us dear. China has to be boldly confronted militarily at every possible conflict scenario and diplomacy needs to raise the ante and make China see reality on ground.

“.. Lackluster approach by British…” –

Lackluster??? – At least the British in spite of all other bad things did in British-India, demarcated the boundary with the then northern neighbour Tibet which was the historic McMahon line. China was not in the picture in that historic past and could not be

. And that McMahon line was drawn with whatever technology was available in that era – remember there was no GPS! As the successor to British-India Delhi inherited a treaty with Lhasa for security and protection, and when China invaded Tibet 1947-49, Tibetan authorities pleaded with Delhi for military help which Nehru reneged on.

Note that all the sovereign territory loss has happened since 1947 and is happening presently is due to spineless India’s political masters to date (excepting Indira Gandhi). China has settled border with Myanmar (Burma) on the basis of the same Mcmahon line. So is the case with Shaksgam Valley – China did recognize the McMahon line with POK there, otherwise there was no necessity of Pakistan signing off that part of Kashmir territory to China.

The British did a few great things for India. The Andaman Islands would be today with Indonesia, had the British not secured that territory. International boundaries between nation-states are decided by fighting wars and India must fight her wars for sovereignty. China has been waging war by “stealth” ever since the 1950s and naively India is succumbing to that. It seems the Indian Army is willing to fight war only with Pakistan and not with China. I am really at a loss at the Indian mindset blaming always others for their own failures as in here “British … ruling over India is now costing us dear…”.

Something that almost many Indians has forgotten. The land that we don’t even show in map. Only way India can get this land is to first become a developed country and develop its military capability far beyond what Chinese have now. Once india will prosper all our lands will come back.