For India’s economic growth to sustain at eight per cent plus per annum, its energy supply must increase at more than six per cent per annum over 30 to 40 years’ time frame. As India is heavily dependent on imported hydrocarbons for its energy needs, the country’s must pursue an energy security strategy that minimises the severity and risks of oil and gas dependency, high prices and geopolitical pressures. India’s energy security strategy should comprise a balanced mix of overseas equity investment in oil and gas sources, astute energy diplomacy to draw up favourable long-term supply and transportation contracts, diversity of supply sources to reduce vulnerability to shock, increase in domestic production, building of sufficient strategic oil reserves to cater for disruptions in supplies during war and peace, energy conservation and realistic reduction in demand, improved efficiency in management of supply-side issues (generation and distribution of electricity) and the gradual substitution of fossil fuels by hydro-electric and nuclear power as well as unconventional sources of energy.

India relies on crude oil imports totalling over 70 per cent of the requirement. According to an estimate by the The Energy and Resources Institute (TERI), New Delhi, this import dependence is expected to increase to over 80 percent…

India’s energy security strategy would be seriously flawed unless due emphasis is given to the security of the sources of supply, the energy infrastructure and the transportation of fuels through pipelines and ships. The aim here is to address some of the concerns related to security issues and to suggest ways and means to overcome the security-related challenges.

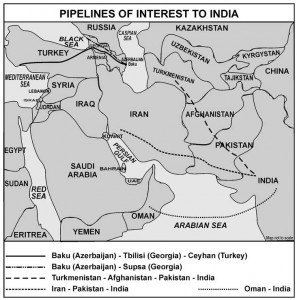

Pipeline Politics: Security of the IPI Pipeline

Trilateral negotiations on an overland natural gas pipeline from Iran to India have been going on for several years but have remained inconclusive. Since the pipeline would run through Pakistan’s Balochistan and Sind provinces, with attendant security risks, discussions of the proposal have tended to generate more heat than light in India. Considering that energy qualifies as a strategic resource in which India is grossly deficient, the issue merits dispassionate consideration, as decisions made today will affect India’s growing economy and national security for decades to come.

India’s energy security continues to be precarious. At present, approximately 40 per cent of India’s energy requirements are supplied by oil and natural gas. Since domestic production has stagnated at around 33 million tonnes, India relies on crude oil imports totalling over 70 per cent of the requirement. According to an estimate by the The Energy and Resources Institute (TERI), New Delhi, this import dependence is expected to increase to over 80 percent by 2010 as the growing economy will demand greater energy supplies and domestic production is expected to increase only marginally. Such a high level of import dependence will make India vulnerable to future oil shocks – occasioned by lower than projected production, disruption in supplies, price volatility and reasons such as economic sanctions.

Hence, it is in India’s strategic interest to, firstly, ensure that the country receives sufficient future oil supplies through the acquisition of overseas sources and astute diplomatic tie ups with friendly oil exporting nations at reasonable prices and, secondly, explore possibilities for alternative energy sources, including a gradual increase in the share of natural gas in the country’s energy basket since it is available in greater abundance and at a lesser cost than oil. India’s present requirement of natural gas is approximately 34 billion cubic metres (BCM) while domestic supply is 26 BCM. The requirement is expected to increase to over 75 BCM by 2010, of which imports will account for almost 58 BCM, which is 76.9 per cent.

India is surrounded by countries with surplus natural gas (Iran, Turkmenistan and Myanmar). However, it has not been possible so far to tap much of this gas on a long-term basis. It is in order to bridge the gap between availability and supply that India is so dependent on Iranian gas. While it would be strategically prudent to diversify and stabilise India’s supply sources and invest in oil equity in various locations across the world, the Persian Gulf region will remain a major source of oil and natural gas for India. Iran is an energy giant with one foot in the Caspian Sea and the second in the Persian Gulf. It is mutually beneficial for India and Iran to enter into a buyer-seller relationship for natural gas as Iran has in abundance and India desperately needs. The geographical location of Iran’s natural gas reserves at the South Pars field is such that the Indian and, to some extent, Pakistani markets are the only major markets that can be profitably served by Iranian gas.

Natural gas is transported either through overland or undersea pipelines in its natural state or as liquefied natural gas (LNG). Transporting LNG in oil tankers is a costly venture. The capital outlay that would need to be incurred would include an expenditure of USD 2 billion for a liquefaction unit, USD 200 million for each LNG tanker and USD 500 million for a re-gasification plant. Considered purely in economic terms, overland pipelines present the most viable commercial option. The 2,200 km overland pipeline from Assaluyeh and Bandar Abbas in Iran, which would pass through Pakistan and link up with the existing HBJ pipeline in Rajasthan, is likely to cost between USD 3 to 4 billion. Since this pipeline would supply natural gas to Pakistan also, the cost would be proportionately shared by India, Iran and Pakistan. The 2,900 km offshore pipeline from Bandar Abbas to Jamnagar, through shallow waters on the Continental Shelf, would cost approximately USD 5 billion, to be shared by India and Iran. The deep-sea option, that is still technologically suspect, would cost almost as much to build, operate and maintain as the LNG option.

India’s present requirement of natural gas is approximately 34 billion cubic metres (BCM) while domestic supply is 26 BCM. The requirement is expected to increase to over 75 BCM, of which imports will account for almost 58 BCM, which is 76.9 per cent.

The overland pipeline option suits Pakistan admirably as it will benefit by netting a transit royalty of USD 700 to 800 million annually, besides getting a regular source of gas with minimal investment. So far, Pakistan has not been able to fully exploit its own gas reserves in Balochistan. Pakistan’s economy is still recovering from the mess that it was in when the country was on the verge of becoming a failed state till Uncle Sam bailed it out after 9/11. A guaranteed inflow of substantial revenues would help Pakistan considerably to stabilise its economy. However, the Baloch people are concerned that Pakistan will not equitably share these revenues with their underdeveloped province.

Though the overland option through Pakistan is economically the most viable, India cannot let good economics translate into bad security. India must not allow the supply of a strategic resource to be held hostage to the spiteful machinations of a capricious government. General Pervez Musharraf’s military regime has stated several times that Pakistan is willing to give a unilateral undertaking that it will not disrupt the supply of gas to India. However, after the Pakistan army’s insidious intrusion into Kargil in 1999, the Pakistan army has completely lost India’s trust. Pakistan must prove that it is capable of ensuring the security of the IPI pipeline if it wishes to garner substantial revenues and gain economically from the proposed pipeline. General Musharraf has admitted that his government has no control over at least some Jehadi organisations that are sending mercenary militants to fight the Indian security forces in Kashmir. It is a moot point whether his government will be able to ensure the physical security of a pipeline that runs for almost 1,500 km through Pakistani territory even if it was keen to do so. Also, the Baloch people are concerned that Pakistan will not equitably share the revenues earned from the pipeline with their underdeveloped province. A fairly vigorous insurgency is sweeping across Balochistan and the gas pipeline will be a lucrative target for scoring political gains. As a Baloch MNA (member of Pakistan’s national assembly) told this author three years ago, the Baloch people will never allow this pipeline to function without frequent disruption unless the Pakistan government shares revenues with them in a ratio with which they are satisfied.

The diameter of the gas pipeline would be between 50 to 55 inches (approximately 1.25 to 1.40 metres). Though such pipelines are mostly buried underground, they are laid just below the surface and their route is well marked to facilitate maintenance, making them prone to easy disruption. The compressor stations that are usually over-ground are also vulnerable to sabotage, but these can be easily guarded. Any terrorist group or disgruntled individual fanatic with a medieval mindset could disrupt the pipeline with a few grammes of plastic explosive or a few hundred grammes of high explosive – commodities that are available in abundance in Pakistan. In fact, in some areas in Pakistan, explosive charges, detonators and cordite are so freely available that one can buy the stuff from the neighbourhood grocer. Under such circumstances, ensuring the security of the pipeline would be a daunting challenge for the most committed police or paramilitary force.

The entire length of the pipeline would need to be fenced off on both sides to deny easy access to prospective saboteurs. Since wire fencing can be easily cut, it would need to be kept under electro-optical surveillance throughout its length, combined with continuous patrolling. Patrolling would tie up large numbers of security personnel and would be possible only if a motorable track is constructed parallel to the fencing. The area would have to be well lit at night. Even if a triple-wire fence, with the inner strand electrified, were constructed on either side of the pipeline, the security force would still have to contend with attempts at tunnelling under the fence. The BSF battalions stationed on the international boundary in the Punjab and Rajasthan sectors, where an electrified fence has been built, are witness to the large number of attempts that are made from Pakistan’s side to tunnel under the fence. All these measures would cost a massive amount to implement and would still not guarantee 100 per cent security.

Fibre-optic based sensing devices would be necessary to detect normal leakages. It would be necessary to create large-scale storage facilities to overcome disruptions and quick-reaction maintenance teams to seal damaged or leaky portions of the pipeline. All of these measures would ad to the cost of construction and maintenance. Hence, it emerges clearly that the overland option is not viable from the security point of view without clear international safeguards. Even an offshore, shallow-water pipeline along the Continental Shelf would be vulnerable to disruption by sea-borne terrorists whom Pakistan could conveniently disown. And, the deep-sea pipeline through international waters, if it is technologically feasible, would be vulnerable to attacks from the Pakistan Navy during times of hostilities when it would be critically important to ensure un-interrupted flow of gas. Protecting such a pipeline would stretch the meagre resources of the Indian Navy.

Though the overland option through Pakistan is economically the most viable, India cannot let good economics translate into bad security.

It would be beneficial to create a stake for Pakistan to ensure the security of the proposed pipeline. This can be done by Pakistani acceptance of petroleum products from Indian companies through pipelines coming in from India. Pakistan will benefit by getting these products at internationally competitive prices and Indian companies will gain by being better able to utilise their refining capacities. This will create a quid pro quo stake in Pakistan and help the Pakistan government to convince the fundamentalist elements that disrupting gas supplies to India will prove costly for Pakistan as well, since India could reciprocate in a similar manner.

There is another option that is often discussed. Instead of a trilateral government-to-government deal between India, Iran and Pakistan, an international consortium of stakeholders could be formed. Such a company could buy the gas from Iran and deliver it to India. The World Bank has expressed its readiness to fund the project. Pakistan would be less likely to allow disruption in the functioning of an international conglomerate, with the attendant risks of economic sanctions being imposed among other punitive measures. Such a consortium would need to incur heavy costs to ensure the security of the pipeline. Also, higher insurance costs, opportunity costs and the need to maintain larger strategic reserves might well make the overland option prohibitively expensive. UNOCAL, a multinational oil and gas company, had ventured out a decade ago to bring oil and gas from the Central Asian Republics to the Arabian Sea and to serve clients enroute, but gave up the idea due to the instability prevailing in Afghanistan and along Pakistan’s western border.

It is a Catch 22 situation indeed! Perhaps the best option for India would be to continue with LNG while simultaneously exploring the possibility of a secure overland route with unimpeachable international guarantees. If India can get gas at the border and has to pay only for what it gets – COD – without sinking its money into capital investment, it would be an option worth exploring. However, even then, India would need to plan ahead for alternative gas supplies for the downstream projects dependent for gas on the IPI pipeline.

Security of India’s Offshore and Overseas Investments

Despite the threat of terrorism emanating from inimical neighbours and terrorism organisations like the LTTE, India’s offshore oil installations are virtually unprotected. Most of these installations belonging to the ONGC and some private companies are well beyond the area of responsibility of the Coast Guard. The Indian Navy has neither been assigned the responsibility to ensure their security nor does it have the personnel and material resources to do so. The offshore infrastructure is vulnerable to threats from the sea (small explosives-ridden boats ramming into the frame supporting the oil platform), from the air and from divers fixing explosive charges after an underwater approach. While the threats are real, nothing has been done to address them.

General Musharraf has admitted that his government has no control over at least some Jehadi organisations that are sending mercenary militants to fight the Indian security forces in Kashmir. It is a moot point whether his government will be able to ensure the physical security of a pipeline…

Approximately 80 per cent of the oil produced by the Gulf States passes through the Straits of Hormuz. Almost 75 to 80 per cent of Chinese and Japanese oil tankers pass through the Straits of Malacca. Oil and LNG tankers carrying supplies to Indian ports are extremely vulnerable to interception at sea. The Persian Gulf has been and will remain the primary source of India’s oil and gas imports for quite some time to come. Over the last couple of years, in terms of piracy and incidents of violence the Persian Gulf waters have overtaken the Malacca Straits as the most dangerous sea-lanes. Besides piracy and minor crime, the Al Qaeda is now active in these waters. Gun running is also a lucrative business. To reduce its dependency on the Malacca Straits, China is reported to have entered into a contract with Myanmar to build one pipeline each for oil (from Sittwe) and gas (probably from Kyaukpu) from the Ararkan coast to Yunnan. China hopes to transport at least 10 per cent of its oil and gas imports through these overland pipelines.

India has acquired substantial oil equity abroad. ONGC Videsh Limited (OVL) has invested USD 3.5 billion in 14 countries in overseas oil and gas exploration since 2000. Oil projects have been launched in Iran, Libya, Gabon, Ivory Coast and Libya. Gas is being prospected in fields in Vietnam, Russia (Sakhalin), Sudan, Iran, Libya, Syria, Myanmar, Australia, and Ivory Coast. In addition, exploration is being planned in Algeria, Australia, Indonesia, Nepal, Russia, Iran, UAE and Venezuela. India’s private companies have invested in projects in Oman, Iran, Yemen, and Africa.

With increasing international oil and gas investments, India has now become a global player in the energy market. However, there are still major differences, both within the government and among policy analysts, on the route that India should take. The mercantilist view is to secure access to sources of energy for exclusive use, pre-empt being denied access to resources and deny access to others. The commercialist view is to earn profits by selling resources at market rates, not necessarily to the Indian market and to contribute to national interest by redirecting profits to other uses. In either case, security interests remain the same. Investments in volatile regions like the Middle East and Africa face risks from terrorists and saboteurs. Assets in unstable Latin American and African countries could be subject to nationalisation at the whims of their leaders. Also, India has large number of workers supporting its energy investments abroad. India already has large ex-pat communities in potentially unstable suppliers in the Middle East, particularly Saudi Arabia. India’s global investment footprint is encouraging Indian workers to venture out further around the world. India must evolve suitable strategies to safeguard its investments and Diaspora around the world.

While the issue can be addressed through cooperation with India’s strategic partners (e.g. US, Iran, Russia, Japan) to some extent, there is an inescapable need to eventually build an unobtrusive forward military presence in close proximity of some of the sites that are located in certain hot spots. For example, offshore Blocks N-34 and N-35, located in Cuba’s Exclusive Economic Zone and operated by OVL (ONGC Videsh Ltd) and six other offshore blocks in which OVL holds a 30 percent stake would be at risk if the Castro regime was to collapse without a suitable replacement regime that is willing to honour the investments made by India in good faith. Intervention would require a multinational force to operate under UN Security Council sanction.

Substantial oil and gas assets in Syria are owned by a 50-50 ONGC/CNPC joint venture. These could be attacked, sabotaged or, in the worst-case scenario, even seized by the Hizbollah. Militants from the Movement for the Emanci-pation of the Nigerian Delta could threaten Indian workers stationed at Indian Oil Corporation’s USD 3.5 billion refinery in the state of Edo. The refinery could even be surrounded and cut off by the rebels and supplies could be disrupted for long periods of time. In April 2007, a consortium led by India’s OVL struck oil and gas in the Farsi offshore block in Iran. This may be India’s biggest overseas hydrocarbon discovery in recent years. When this block is finally ready for commercial exploitation, it will be a daunting task to ensure the security of the infrastructure put up there.

In another plausible scenario, in case the US and its Coalition partners launch air strikes against Iran’s nuclear facilities, Iran could seriously disrupt oil trade by closing the Straits of Hormuz. It could even attack oil platforms and shipping in the Gulf. Edward Luttwak has pointed out that, “all of the offshore oil and gas-production platforms in the gulf, all the traffic of oil and gas tankers originating from the jetties of the Arabian peninsula and Iraq, are within easy reach of the Iranian coast”.

Even an offshore, shallow-water pipeline along the Continental Shelf would be vulnerable to disruption by sea-borne terrorists whom Pakistan could conveniently disown.

However, the repercussions of such action would be far-reaching and the international community is bound to close ranks to respond suitably and India will also be constrained to join the effort. However, as oil trade accounts for about 80 per cent of Iran’s exports, it would be counter-productive for Iran to disrupt international oil supplies for a long duration.

Readiness for a Military Response

Though some of the above scenarios might appear far-fetched at present, these may soon turn out to be real threats that require hard political and military responses. The emerging threats have a direct bearing on India’s future energy security. The options available are to both partner friendly powers to ensure the security of India’s international oil and gas sources and infrastructure and, when necessary, to go it alone during a crisis with limited logistics support from outside. India now needs to project power to deter interference by non-state actors and terrorist organisations in its oil and gas investments. In order to do so, India must build the necessary rapid deployment capability by way of strategic airlift, air assault and amphibious assault, besides the mandatory Special Forces capability that has become de rigueur in the prevailing strategic environment.

India must create a military capability to launch a tri-Service air assault brigade group within 48 to 72 hours from the time that the first warning order is received by HQ Integrated Defence Staff (IDS), with the first infantry battalion being launched within 24 hours. This capability must be put in place by the end of the 11th defence Plan in March 2012. By the end of the 12th Defence Plan in March 2017, the capability must be upgraded to one rapid deployment division comprising an air assault brigade group, an amphibious brigade group and an infantry brigade group. Constituting such forces, even within existing manpower ceilings, is undoubtedly a costly capital-intensive venture. However, the funds need to be found so that India is ready to intervene militarily in keeping with its enhanced regional responsibilities and to safeguard energy security.

Equity oil investments overseas have several limitations and cannot shelter India from the ever-present volatility in the oil markets. Guaranteeing the physical security of oil and gas infrastructure and supplies from distant fields will always be a serious challenge. While there is no requirement at present for a permanent military presence to safeguard India’s energy investments abroad, India must be prepared to use all available tools, including military intervention, to restore normalcy if energy access and supply is threatened or actually disrupted. Current efforts to gradually build a presence include military logistics support to Kazakhstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan; military cooperation with several Southeast Asian states (Vietnam, Indonesia, Malaysia, Laos, Singapore, Thailand); naval exercises and interaction with African countries, Iran and some of the Gulf states – Oman and the UAE; and, infrastructure, logistics and material support to Myanmar to contain Chinese influence. These efforts need to be strengthened further in the interest of India’s energy security.