In late eighties, two million people visited Vaishno Devi Shrine every year compared to half a million tourists visiting Kashmir. Yet 90 per cent of the tourism budget was allotted to Kashmir.

Jammu contributes 70 per cent of the State’s revenue, whereas only 30 per cent of its total expenditure is incurred on it.

Out of a total of 450,000 government/semi-government employees in the State, 330,000, come from the Valley. Jammu and Ladakh are grossly under represented; the former having only 15 per cent representation in the civil secretariat. At the secretary level, Jammu’s share is 8 per cent. Ladakh’s representation in civil secretariat is only 0.68 per cent. The unemployment figures in Jammu and Ladakh are 69 per cent, which is far higher than that in the Valley, where it is 30 per cent (2006 figures). Between 1990 and 2006, state government employed 265,000 persons; only 345 of these were Kashmiri Pandits.

Jammu contributes 70 per cent of the State’s revenue, whereas only 30 per cent of its total expenditure is incurred on it. Since 1996, the state created 155,000 job opportunities; Jammu got only 15,000 of these, remaining went to the valley. “At an average, 6000,000 tourists visit Jammu every year and only 200,000 visit Kashmir, yet 90 per cent of tourism expenditure goes to the Valley,” says Dina Nath Mishra.

The discrimination against Jammu and Ladakh is further compounded when even developmental works are carried out with a heavy bias towards the Valley. As Dr Hari Om, writing in the Indian Express of July 17, 2002 states, “Chenani is the only power project in Jammu, producing a paltry 22 MW of power. The rest of the projects, Upper Jhelum, Lower Jhelum, Upper Sindh, Mohra and Ganderbal, etc. are all in the Valley, with a production capacity of 328 MW. While only Rs. 10 crores has been spent on Chenani project, Rs. 500 crores has been spent on the Kashmir plants.” Major factories like the cement factory, Hindustan Machine Tools and telephone factory, are all located in Kashmir itself. Writing about the state of other infrastructural projects, Hari Om states, “Jammu has a total area of 26,293 sq kms and Kashmir 15,853 sq kms. In 1987, Jammu had 3,500 kms of roads, covering 18 per cent of this area, whereas Kashmir had 4,900 kms, covering more than 40 per cent of the area.”

…Jammu had 3,500 kms of roads, covering 18 per cent of this area, whereas Kashmir had 4,900 kms, covering more than 40 per cent of the area.”

The tilt towards the Valley extends to even the number of professional colleges and technical institutes opened in the State. Whereas Kashmir boasts of Post-graduate Sher-e-Kashmir Institute of Medical Sciences, dental college, veterinary college, Agriculture University, Regional Engineering College, the Artificial Limb Centre, Institute of Hotel Management and Physical Training Institute: Jammu has one ill-equipped medical college and a small under-staffed engineering college which does not even have a full range of equipment. The agriculture and Ayurvedic colleges in Jammu have been closed down. In the admissions to Regional Engineering College and Agricultural University, the share of Jammu province is only 30 per cent.

Mata Vaishno Devi University was established in Jammu after the proposal was rejected by the government on many occasions, on one pretext or the other. Even when the proposal was finally accepted, the university was set up by the Vaishno Devi Trust, using funds collected from pilgrims. The Trust had to shell out Rs. 13 crores to purchase the land at commercial rates. On the other hand, Baba Ghulam Shah Badshah University, set up as a counter move in Rajouri, was funded by the State Wakf Council headed by Mufti Mohammad Syed, the then Chief Minister, who also gave it a huge chunk of forest land, free of cost.

In 1986, the Prime Minister announced an aid package of approximately Rs. 180 crores for the state. Out of this, Jammu got Rs. 15.5 crores, and Kashmir, Rs. 70.06 crores. The remaining amount of Rs. 92.76 crores was meant to be spent on the common development projects of the entire state, but actually it turned out that more than Rs. 50 crores was allocated to Kashmir.

…economic advantages enjoyed by the Valley Muslims, Kashmiri Pandits exodus from the valley in 1990 has further improved their economic status.

To add to all these economic advantages enjoyed by the Valley Muslims, Kashmiri Pandits exodus from the valley in 1990 has further improved their economic status. Huge chunks of agricultural and non-agricultural land left behind by Pandits (some estimates put it at 14,000 hectares of agricultural land alone) has been illegally appropriated by them. Besides, continued life in exile compelled a large number of Pandits to resort to distress sale of their properties. “99 per cent of the sale of houses by Pandits was termed as distress sale.”14 Such distress sale, particularly in the initial years of militancy, further contributed to enriching the Kashmiri Muslims. A clear indication of improved economic status of Kashmiri Muslims is the fact that in every home, whenever there is some function, jewellery is presented as gifts to the guests. “Now, even diamonds are becoming popular. It was not so earlier,” says Nisar Ahmed, a shop-owner.

Additionally, what contributed substantially to the economic betterment of Kashmiri Muslims was that they got to fill-in thousands of government posts which were created as a result of Pandit’s exodus from Kashmir. Besides, the posts vacated by Pandits in the State government services while retiring every month, too got filled by Kashmiri Muslims as none was recruited from amongst the former. By 2007, approximately 72 per cent of state government Pandit employees had retired and these posts were filled up by Kashmiri Muslims. After more than two decades of their exodus, the State government, on instructions from the centre, has recently recruited 3,000 Pandits, though their service conditions stipulate that they need to serve in Kashmir. How many will take up these jobs is, therefore, a moot point.

It is because of all these reasons that one does not get to see the same stark poverty in Kashmir Valley, as one gets to see in the rural areas of rest of India.

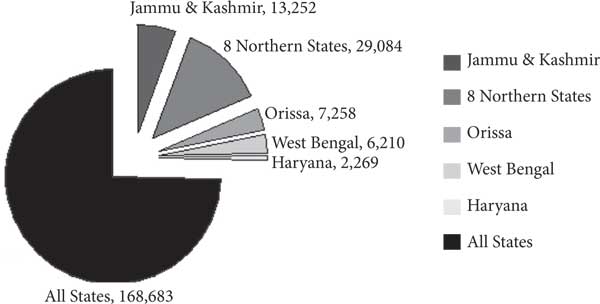

The combined grant received by the eight north-eastern states during the same period was Rs. 29,084 cores; 44 per cent of their entire expenditure. This is significantly lower than that of Jammu and Kashmir.

Compare this with PoK, if only to bring out the fact that Kashmiris are better off than those living across the LoC. World Bank report of July 2002, stated that 88 per cent people in PoK live in rural areas, depending on forestry and agriculture. Unemployment ranges between 35 to 50 per cent. Literacy, till recently, was only 10 per cent, though it has now risen to 48 per cent. Sixty per cent of the population has no access to drinking water. Whereas, per capita income of Pakistan was 420 $ (Rs. 21000) in 2006, in PoK it was 185–200 $ (Rs. 9,500).

Present Economic Realities of the State

Government of India has poured in thousands of crores of rupees into the State in the past two decades of insurgency, to help some specific sectors, like tourism, which were hard hit by insurgency. Before militancy set in, tourism contributed Rs. 500 crores per annum to the State’s economy. The tourist inflow, which had reached a peak of 730,000 in 1978–79, was reduced to a few thousand after violence broke out in Kashmir. Public infrastructure also suffered great damage due to neglect and violence. Between 1989 and 1996, about 725 educational institutions and 303 bridges and culverts had been destroyed. The negligible recovery of taxes and revenues during the nineties further increased the non-plan deficit. Consequently, the State’s economic dependence on the centre further increased in the recent past.

Reserve Bank of India’s figures (2009–2010) clearly point out the deep financial mess the State is in. In 2009–2010, it received 60 per cent of its total expenditure, amounting to Rs. 13,252 corers, as grants. Between 1989–90 and 2009–2010 (militancy period), the state received a total of Rs. 94,409 crores, as grants. During the decade between 1994–95 and 2005–2006, the state got 10–12 per cent of the total amount disbursed as grants to all the states of the country. Though, in 2009–2010, it had marginally dipped to eight per cent. Such high level of grants, compared to its ratio of the entire population of the country (nearly one per cent) proves that the Central government has been more than kind to the State. The inflow of goods into the Valley also increased from Rs. 1,157.33 crores in 1989–90 to Rs. 2,536.53 crores in 1994–1995 (the worst period of militancy). During the same period, the outflow of goods from the Valley also increased by nearly 50 per cent.

Only 30 per cent of the aggregate expenditure of the State is incurred on social sectors, i.e. schools, health and rural development — fourth lowest among all states. This is against the national average of the 40 per cent.

Compare this with the centre’s attitude towards the perennially insurgency-hit north-east. The combined grant received by the eight north-eastern states during the same period was Rs. 29,084 cores; 44 per cent of their entire expenditure. This is significantly lower than that of Jammu and Kashmir.

Mis-utilisation of these funds by Jammu and Kashmir has often raised many eye brows. Only 30 per cent of the aggregate expenditure of the State is incurred on social sectors, i.e. schools, health and rural development — fourth lowest among all states. This is against the national average of the 40 per cent.

Despite militancy being at peak during 1990–1995, 6,428 villages were brought under new water supply scheme, besides executing two master plans for Jammu and Srinagar, respectively. Similarly, handicraft production in Kashmir Valley, which in 1974–75 was Rs. 200 million, rose to Rs. 2,400 million in 1993–94. Export of handicrafts also registered a jump from Rs. 75 million to Rs. 2,130 million during the same period. In 1993–94 alone, 3,617 health centres were set up. The enrollment of primary school students also went up from 745,000 in 1989–90 to 940,000 in 1994–95. The State employs 350,000 people, whereas Rajasthan, which is five times the size of Jammu and Kashmir employs only 600,000 people. For the Tenth Five-Year Plan, it got a per capita allocation of Rs. 14,399, compared to Rs. 2,536 for Bihar and Rs. 5,177 for Orrisa.

Administrative expenditure of Jammu and Kashmir is nearly 12 per cent of its overall expenditure. Some might argue that such high level of expenditure is attributable to the State’s mountainous terrain and its disturbed conditions. But Himachal and Sikkim, both mountainous regions, spend only six per cent on administrative expenditure. Another pointer to the woeful state of financial affairs of the state is its per-capita spending. In Sikkim, Mizoram and Arunachal Pradesh (all mountainous states and also affected by militancy in varying degrees), the per capita spending is Rs. 59 lakhs, Rs. 35 lakhs and Rs. 38 lakhs, respectively (figures for 2009–2010). In Jammu and Kashmir, it is only Rs. 20 lakhs. This clearly shows that not enough money is being spent by the State on projects that would have benefited the people directly. One of the reasons is that the State is not generating enough revenue of its own. Besides, there are legitimate doubts whether even the money being shown as spent, was in fact spent at all. Incidentally, not long ago the State was rated as the second most corrupt state among all Indian States by the Berlin-based International Corruption Watchdog, ‘The Transparency International.’ As Mohan Guruswamy and Jeevan Prakash Mohanty have stated, “Talk to even the most ardent pro-India Kashmiri, and he will tell you that politicians and bureaucrats have stolen most of the money. Lending credence to this is the amazing explosion of new construction in evidence all over Kashmir Valley. It is believed that every second house belongs to a government employee or one connected with it. Relate this to the low poverty level in the State and it would seem that trickle-down economics works.”15

Grants from Central Govt. (Rs. in Crores): Share of Total State Expenditure (%). Source: Times of India, July 19, 2010

That the so-called economic backwardness was the cause of breaking out of insurgency in Kashmir has been refuted by no less than its youthful Chief Minister, Omar Abdullah. Speaking on the occasion of inauguration of Qazigund-Anantnag railway line on October 28, 2009, he said, “Kashmir issue cannot be resolved through the flow of money. It was the politics, not the urge for money that drove the Kashmiri youth to take up arms twenty years back.”

Notes

1. House boats are synonymous with tourist industry in Kashmir. Tourists live in these magnificent boats, anchored in the serene and placid waters of Dal and Nagin lakes of Kashmir. Incidentally, it was a Kashmiri Pandit, Narain Das, who constructed the first house boat in Kashmir. “Narain Das was one of the first five Kashmiris to learn English from Rev. Doxy, the founder of famous Kashmir Mission School in 1982,” says the book Keys to Kashmir. He was the father of the renowned Shaivite philosopher of recent times, Swami Laxman Joo. Narain Das had opened a small store to cater to the needs of European visitors, who had started flocking to Kashmir in large numbers at the turn of nineteenth century.

Once his store was destroyed in fire, and not finding a suitable place to run the strore from, he shifted to a doonga. This shifting turned out to be a blessing in disguise as the doonga could be moved to a convenient location for visitors and moored there. When rain and snow destroyed the matting walls and hay roof of his new store, he replaced these with wooden planks and shingles. A British officer once took fancy to his doonga and purchased it from Narain Das, who found the deal quite profitable. Thereafter, Narain Das started constructing doonga and gave up the business of running stores.

Narain Das had also developed trade relations with some companies belonging to Western countries. One of these was Koch Burns Agency, which too ran a departmental store from a doonga, parked on the Jhelum, near Shivpora in Srinagar. “In 1885, the Koch Burns Agency shifted to Chinar Bagh near Dalgate. Once a customer of the Agency, Dr Knight, suggested to Narain Das that he should make some modifications to the doonga to make it more attractive and convenient for the tourists to live in,” says Inder Krishen Raina, a grand nephew of Narain Das. The latter found the idea interesting and carried out the required modifications. By July 4, 1890, after much trial and error, the first house boat was ready for commercial use of tourists. However, constant improvement in design and aesthetics continued till many years thereafter. With vital inputs from Colonel R Sartorius, V.C., and some other Englishmen, the first double storey house boat, named ‘Victory’, was constructed in 1918. This had led to Narain Das being known by the nick name Nav Narain (Nav, meaning boat).

The boats are made of quality cedar wood available in deep forests of northwest Kashmir.

2. Dr MK Teng and CL Gadoo, White Paper on Kashmir for Joint Human Rights Committee for Minorities in Kashmir (Gupta Print Services).

3. Binish Gulzar and Syed Rakshanda Suman; Pioneer, August 25, 2009.

4. Shankar Aiyer, India Today, October 14, 2002, p. 36.

5. Mohan Guruswamy and Jeevan Prakash Mohanty, Jammu and Kashmir: Is there really a fresh vision and a new blueprint? Centre for Policy Alternatives (CPAS), New Delhi.

6. Shankar Aiyer, n. 4.

7. Ibid.

8. Ibid.

9. Mohan Guruswamy and Jeevan Prakash Mohanty, n. 5.

10. Ibid.

11. Joginder Singh, Pioneer, February 11, 2008.

12. Inside Kashmir-3, Times of India, August 2, 2010.

13. Times of India, January 22, 2011.

14. Prof Hari Om, Kashmir Sentinel, December, 2006.

15. Mohan Guruswamy and Jeevan Prakash Mohanty, n. 5.

article clearly shows how shrewdly porki sympathizers in Kashmir conspired against Kashmiri Pandits and we had no clue what was going on there .all the political parties at center are responsible for Ignoring plight of Kashmiri Pandits my heart goes out for them ,i am really sorry as an Indian and as an Hindu