Defence industrialisation strategy must be made a part of the overall national manufacturing capability strategy. The social sector, through their social overheads and infrastructure improvement as the building block for economic development, must be part of the overall development strategy. Accordingly, indirect offsets must be part of the offset policy with a mix of direct and indirect offset options as many countries practice. Defence technology funding recommended by Defence Production Policy (2011) must be operationalised early. Else, the pious platitude of improving self-reliance through the offset policy in critical technology will remain a pipe dream.

India’s Offset Policy of 2005 aimed at leveraging our big ticket arms acquisition for bringing in outsourcing arrangements, FDI in infrastructure and R&D, and boosting exports with a view to bolster our indigenous military industry capability. The subsequent updates introduced offset banking, a level playing field for the private sector in the shipbuilding sector and included civil aerospace and homeland security products in its ambit. Based on India’s experience in offset realisation so far which has basically has brought in outsourcing of low-end products and services, training, simulation and ROH capability, there have been very lukewarm responses to FDI inflow as well as Joint Venture arrangements with global OEMs and design houses. This has led earnest critics to stridently suggest the inclusion of technology transfer, multiplier, increase in the offset banking period and commercial shipbuilding in the ambit of offset policy besides revamping the existing implementation arrangements under the aegis of the Defence Offset Facilitation Agency (DOFA).

The Defence Production Policy 2011 made pious suggestions to bolster India’s self-reliance in critical areas of technology…

The Defence Production Policy 2011 made pious suggestions to bolster India’s self-reliance in critical areas of technology by creating the necessary conditions for technology funding through Public Private Partnership. The Joint Venture guidelines have also been issued on January 17, 2012, by the MoD for kick-starting this process while underscoring the need for greater transparency in forging such alliances.

In a major departure from the earlier policy, the new offset policy now includes technology transfer, multipliers and commercial shipbuilding sector in its ambit. The increase in the banking period for offsets to seven to ten years is also a step in the right direction as it will give the requisite leeway for forging partnerships between the Indian industry and global OEMs. There are also suggestions to revamp and reinvigorate the DOFA.

These new policy initiatives though late in coming are really welcome. However, some of the issues that would need to be carefully addressed for these new initiatives to succeed are enumerated below:

Technology Transfer

The DPP provides for various windows for technology transfer through the ‘Buy and Make’ option to the DPSUs and OFs. DPP-2009 included the Buy and Make (Indian) option which provided a window to the private sector as technology recipient. Inclusion of technology in the ‘Buy’ option now through offset routes is an added option now.

It would be necessary for the Services, DPSUs/OFs and DRDO to identify not only the priority areas for technology transfer but also make a clear choice of technology which should be leveraged through the ‘Buy and Make’ as well as the ‘Buy’ option. It is quite likely that outdated technology would be palmed off in the ‘Buy’ option unless the RFP clearly identifies the targeted technology and its currency. Evaluation of cost of technology is another challenging area.

The new offset policy now includes technology transfer, multipliers and commercial shipbuilding sector…

Technology is often linked to export promotion and offset credit is predicated on its impact on exports. This is a very effective strategy adapted by Turkey. Israel has become a major defence exporter by targeting key technologies such as FPA, Seekers, Communication equipments and UAVs from the USA. These are useful templates for India.

In the mother of all contracts, the ‘MMRCA’ where 50 per cent offsets are expected (approximately $10 billion) efforts should be made to get key technologies from selected vendors of components such as the AESA Radar, single crystal blade and special coatings. India must not miss out on this opportunity now that technology transfer is part of the offset credit for the Rafale.

Multiplier

Providing higher credit for preferred technology, skill upgradation and training is practiced by every country. This has to be worked out by an Empowered Committee representing the DRDO, Services and DPSU/OFs as they would be able to flag the serious gaps in our design and manufacturing capability.

Evaluation of cost of technology is another challenging area…

At present, the Civil Aviation industry provides multiplier in its offset arrangements for Boeing and Air Bus. Since both the civil aviation and military aviation sectors would be looked at in a holistic manner, a coordinated effort is needed to rationalise the application of multiplier in this sector.

Credit Banking

While increase in the banking period is welcome, it ought to be operationalised in right earnest. As of now, the arrangement for approval of banking proposals is extremely dilatory and mired in red-tapism in the DPP. Since such initiatives encourage OEMs and design houses to explore potential JV and co-development partners in India, more alert institutional arrangements in quick time would send the right signals.

Commercial Shipbuilding

The Krishnamurthi Committee (2007) appointed by the Government to suggest ways and means to bolster manufacturing capability had flagged the need to look at both commercial and warship building in unison.

In fact, with the increased focus on coastal surveillance, a large number of patrolling vessels are being ordered by the Navy, the Indian Coast Guard as well as the state government authorities. Besides, a large number of tankers and LPGs are on order. The capacity of India’s shipbuilding, both in the Public and Private sector is almost 50 per cent of the large orders in the pipeline. Countries such as South Korea and China have had a real headstart in the shipbuilding sector by focusing on manufacturing and design capability.

Offset realisation would need to be entrusted to an independent empowered agency on similar lines like the TRAI…

For the offset policy to be successful in the commercial shipbuilding sector, the subsidy scheme must be revived immediately as implication of removal of such subsidies has led to disastrous consequences as the following Table 1 would reveal.

Revamping the DOFA

All stakeholders have been unequivocal about the ineffectiveness of the present implementation arrangements through the DOFA. In the UK, a separate agency has been created to ensure better interface with the industry and Implementation Practice (IP). In India, the DOFA is an advisory body under the DPP while for the Acquisition Wing, the driver is acquisition. The offset arrangement is only subsidiary to the main supply contract. There is thus no real stakeholding for the offset realisation in the existing arrangement.

Offset realisation would, therefore, need to be entrusted to an independent empowered agency on similar lines like the TRAI, to interface effectively and impartially with the Indian defence industry and global majors, instead of sheltering cost-ineffective DPSUs/OFs.

The new initiatives, however, do not address two major policy issues viz. increase in FDI in defence and inclusion of indirect offsets. The succeeding paragraphs bring out these concerns.

FDI Policy

The FDI cap in India remains at 26 per cent. Global experience in this regard shows that countries such as China and Malaysia have shown a high degree of pragmatism by allowing higher FDI in their major manufacturing projects. China permitted FDI of 76 per cent in its JV to M/s Embraer. Malaysia also increased its FDI substantially in the manufacturing sector. This has enabled countries to have substantial manufacturing base in the aircraft Industry and increase its global share in manufacturing significantly. Therefore, India cannot be impervious to this concern any longer as every major OEM and design house would like to have a major say in the management decisions which will have significant bearing on the Return on Investment (ROI). Countries who have profited from offsets have tried to take advantage of their labour arbitrage and skilled labour by making their country the preferred destination in the OEMs’ global supply chain.

Countries such as China and Malaysia have shown a high degree of pragmatism by allowing higher FDI in their major manufacturing projects…

It would not be out of place to mention that, in India also, the JV for the Brahmos cruise missile programme there is 50:50 partnership between India and Russia. This programme has witnessed significant volume of production with excellent export potential. Further, in the newly forged JV for the Multi Role Transport Programme between HAL and SDB, Russian Prime Minister Putin, in a recent address to the industries, highlighted the significant role of their partnership with India. This will ensure significant strides in the manufacturing capability of HAL in building mid-segment transport aircraft in a very cost effective manner with export potential.

Therefore, there is a strong case for increasing our FDI cap in defence to at least 50 per cent. There is a critical linkage between FDI limit and technology infusion.

The success of a flexible FDI policy is critically dependent on how it is managed for the benefit of the domestic industry. Some lessons in this regard can be drawn from the practices of other countries, and primarily of China which has used FDI as an instrument for developing its strategic industries.

- China’s FDI policy is geared towards enabling its industries to “integrate into the global value-chain…accelerate its industrial and technological transformation [while avoiding reinvention] of the technological wheel.” The key elements of China’s FDI policy are those of direction, domestic value addition and transfer of technology.

- China is quite “explicit in the type of foreign investment that is ‘prohibited’, ‘permitted’, or ‘encouraged’, with the latter category focusing on advanced technologies.” To induce foreign investors into its high-tech industries China provides various incentives such as tax rebates and lower tariff rates.

- India’s FIPB, while reviewing the incoming FDI proposal, needs to adopt a similar approach in order to ensure that the FDI leads to technology transfer to Indian companies and their value addition is increased over the years. Various incentives such as tax rebates and the like could also be provided to induce higher technology through FDI.

Level Playing Field

There is one more issue and that is a level playing field, which private industry has been constantly clamouring for in the matter of taxes and duties.

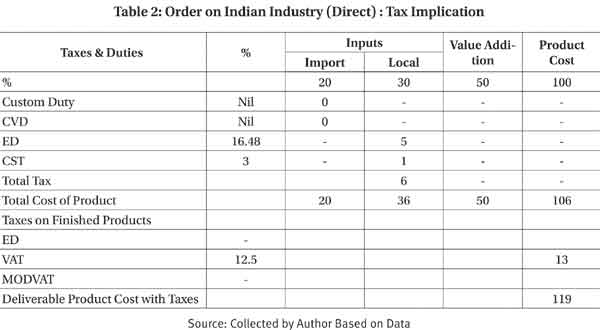

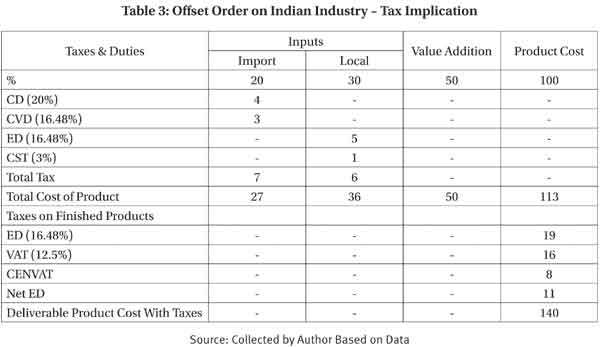

Private industry feels that the offset benefit reduces from 30 per cent to 21 per cent* because of the present structure of taxes and duties. This is an anomalous situation as in the Buy (Global) category the ED, ST element of the Indian competitor is ignored while foreign supplier’s CIF cost is taken into account for determining L1. However, for an Indian partner discharging offset commitment for an Indian programme, all these demands including CD on import elements are charged. Tables placed below will explain this position.

The Indian Industry also feels that the MoD treats offsets on par with indigenous suppliers to the MoD or treats them as export. An empowered Committee should finalise these long pending issues.

Indirect Offsets

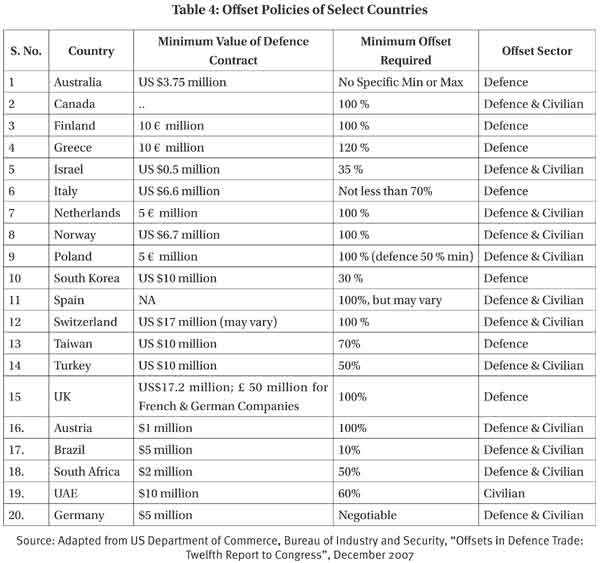

The other disappointment in the new policy has been overlooking the large range of indirect offset benefits which the policy should have availed as many countries do. As would be seen from the following Table, most of the countries have a combination of both Civil and Defence sectors in their offset policy. Besides, the minimum value of contract for offsets is far lower than the threshold in vogue in India’s offset policy.

It would thus be seen that 60 per cent of the countries opt for both direct and indirect offsets, while the rest target defence-specific or civil sector benefits. In the USA, from 1993 to 2009, the total contract value of offsets was $76 billion with 46 countries. Of these, 37 per cent was direct and 63 per cent, indirect. Eriksson, in his study of European defence industries of the period between 2000 and 2005, brings out that offset deals worth $4.2 billion were concluded of which direct offsets were 40 per cent, while indirect defence offsets and civil indirect offsets were 35 per cent and 25 per cent respectively.

There is a critical linkage between FDI limit and technology infusion…

As per the Twelfth Plan (2012-2017), India’s total fund requirement for infrastructure development will be around $1,025 billion according to the Economic Survey, 2010-2011. It has been proposed that such massive funding requirement is provided through 50:50 public partnerships as against 70:30 which was the experience during the Eleventh Plan. This entails massive investment requirement in different core industry sectors. The growth trends in the core industry sectors are given in the Table below.

Besides, the social sector is an underdeveloped segment in India, as India ranks 119 out of 169 countries with a score of 0.519 in the Human Development Index. The trend in the social sector expenditure as a percentage to central government expenditure and GDP is indicated in Table below:

It would be seen from the above tables that infrastructure sector, particularly the telecom sector shows significant growth momentum because of the liberal FDI policy. However, the allocation to social sectors remains abysmally low (four to five per cent) compared to developed countries which spend close to ten per cent of their GDP on education and health. Besides, close to 22 per cent of India’s population live below subsistence level (Poverty Line) with very little growth in employment in the organised sector (-0.65 per cent in the public sector and 1.75 per cent in the private sector) during 2009 -2010. The massive investment needs in infrastructure need to be complemented with human resource development and inclusive growth. The offset policy must include these sectors as part of the indirect offsets. The key to success would be by putting in place a proper manufacturing, and social sector policy by dove-tailing defence industry capability as a subset of this larger policy mosaic.

Conclusion

India embarked on the liberalisation path in 1991 by dismantling the license-and-quota-permit-raj. In the defence sector, the wave of liberalisation came a decade later by encouraging 100 per cent private sector participation and allowing 26 per cent FDI. The half-baked policy of 2005 has now embraced a larger canvass by including technology transfer, multiplier and civil aerospace, homeland security and civil shipbuilding sectors in its ambit. However, the expectation of critical technology inflow and concomitantly improvement in SRI in critical sub systems like weapons, propulsion and sensors are unlikely to materialise unless the FDI policy is further liberalised. Defence industrialisation strategy must be made a part of the overall national manufacturing capability strategy. The social sector through its social overheads and infrastructure improvement as the building block for economic development must be part of the overall development strategy. Accordingly, indirect offsets must be part of the offset policy with a mix of direct and indirect offset options as many countries practice. Defence cannot be a holy cow looking with blinkers at a national development strategy. Furthermore, a significant mark up in investment in R&D by all stakeholders will facilitate technology absorption. Defence technology funding recommended by Defence Production Policy (2011) must be operationalised early. Else, the pious platitude of improving self-reliance through the offset policy in critical technology will remain a pipe dream.