From time to time, the Defence Procurement Procedure has tried to bring in level playing field to the private players. DPP-2011 has been significant as it has brought in some of the ship-building contracts in the ambit of competition. However, there are nagging areas where the private players are being discriminated, for example, the Exchange Rate Variation (ERV) which is available only to the DPSU, as per DPP. There is also a discriminatory practice in the area of giving CDE to DPSU and private players.

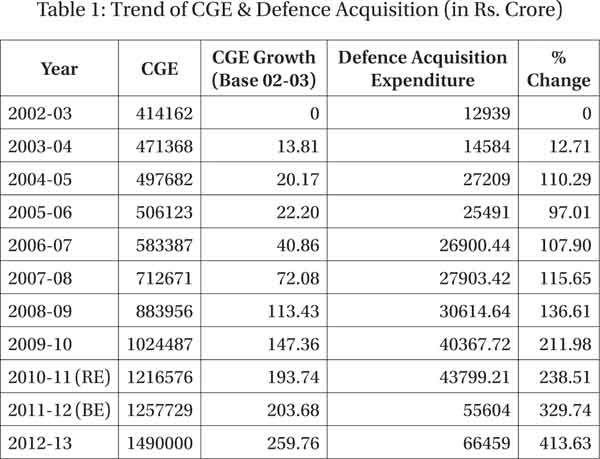

India is the largest importer of conventional arms in the world accounting for nearly 10 per cent share in the total global arms imports as per the estimates of SIPRI 2011. Since the Kargil conflict in 1999, India is said to have inked $50 billion worth of arms deals. The increased focus on modernisation of the defence services is evident from the increase in acquisition budget compared to the total Central Government expenditure, during the last decade.

Between 2002-2003 and 2011-2012 the acquisition budget has increased by nearly 330 per cent…

While the volume of arms import is a source of concern among India’s neighbours/ adversaries, defence analysts are primarily concerned with the way that acquisition of major systems/platforms are interminably delayed and funds surrendered repeatedly against modernisation allocation.

The paper attempts to provide insights into some of the systemic issues which contribute to such delays and suggests a more streamlined acquisition process as well as the definitive changes needed to ensure synergy amongst stakeholders.

Budget Utilisation Trends

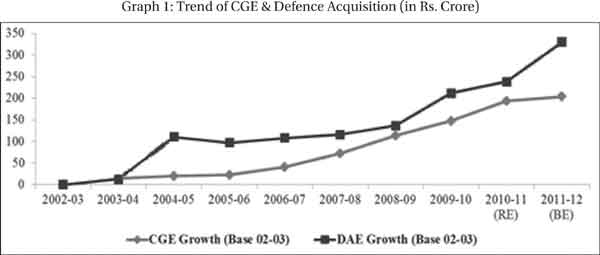

Between 2002-2003 and 2011-2012, the acquisition budget increased by nearly 330 per cent compared to a 200 per cent growth in Central Government expenditure – a phenomenon elegantly termed as ‘Military Malthusianism’ where increase in acquisition budget far outstrips the increase in Central Government expenditure.

Table 1 brings out this dissonance.

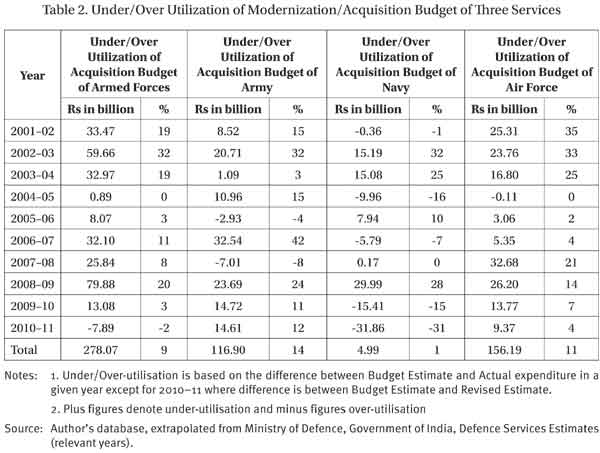

Despite the massive spurt in acquisition budget, particularly during the last four years, the recurring concern amongst discerning observers and also the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Defence is the surrender of acquisition funds year after year. For instance, during the past decade, the Ministry of Defence (MoD) has surrendered a cumulative total of Rs. 358.8 billion with annual surrenders varying between 4 to 31 per cent with overall under-utilisation being of the order of 11 per cent. The surrender of funds is across the services although Navy has a more edifying record of budget utilisation in the recent years. The Indian Army has been the major defaulter.

These surrenders are all the more stark if the 14 per cent budget cut generally exercised by the MoF to the MoD projection is taken into account.

While many reasons are adduced for such massive surrenders viz. prevarication in decision making, sweeping criticism by oversight agencies encouraging inertia, absence of CDS, civil-military stand-off and the lack of long term planning, the paper attempts to flag some of the systemic issues which need to be addressed to ensure a more integrated and efficient approach to acquisition.

Formulation of Services Qualitative Requirements

As per Defence Procurement Procedure 2011, a good Services Qualitative Requirement (SQR) should, in a comprehensive, structured and concrete manner, lay down the user’s requirements, which are broad based and realistic, of contemporary technology with performance parameters verifiable and all parameters being classified as ‘Essential’.

The Army HQ has a General Staff Qualitative Requirement (GSQR) Cell which is the central point for vetting all draft GSQR before they are submitted to the General Staff Equipment Procurement Committee (GSEPC). Collegiate vetting is done by different agencies like DRDO, DGQA and DDP to arrive at the parameters. Similar structures are in place at the Naval and Air HQ.

A close study of past cases reveals that the GSQRs were revised more than four times in a span of six years and almost 75 per cent of the cases had undergone at least two revisions. The delay in acquisition at the GSQR stage itself is about 68 per cent as against other reasons. A few of such case studies are recounted below.

India is the largest importer of conventional arms in the world accounting for nearly 10 per cent share in the total global arms imports…

In a case involving the Mines Scattering System, the process of preparation of SQR commenced in 2005 and the GSQR approved in May 2006. This was amended thrice. Some of the shortcomings noticed in this case are repeated amendments to parameters such as traverse which has been changed from 360 degrees to 270 degrees in the first amendment and to 180 degrees in the second amendment.

In another case involving Low Level Highly Mobile Radars, requirement of which was felt in 1999, the operational requirements could not be met with by the vendor because it contained aspects beyond the capability of vendors at that time. After the Technical Evaluation Committee (TEC) recommended rationalisation of operational requirement, Defence Acquisition Council (DAC) accorded approval in September 2004 as ‘Buy and Make’. The RFP, issued in January, 2006 had to be retracted due to vendor’s inability to meet the communication equipment requirements as these were erroneously included as essential operational requirements. A fresh RFP issued in July 2007 led to the conclusion of the contract in January 2009. In this case, it was seen that the initial RFP floated was too ambitious and the inclusion of communication equipment in the RFP when the vendor did not have manufacturing capabilities, led to a further delay of two years.

Further, as per para 14 of DPP-2011, the SEPC should assess that the QRs being approved should ideally result in a multi-vendor situation. Yet the CAG Report (2007) brought out that during 2003-2006, 60 per cent of the capital acquisition witnessed single tender/resultant single tender situation. Such single tender situation gets further aggravated by the phenomenon of ‘tail wagging the dog’. Very often the Services pitch for single tender RFP based on common maintenance arrangement. A case in point is the UAV where Army plumped for single vendor (IAI Malat) in the RFP on the basis of such maintenance convenience. While this argument has some substance, it cannot be stretched indefinitely by preempting competition and cost effectiveness. A mix of platforms, as in the case of fighter aircraft, has its operational advantages also.

Costing is one area where the professional expertise in the DDP is quite inadequate…

Non-updation of QRs with efflux of time is a grey area. A case in point is the acquisition of UAVs for the Army when, in 2004, the MoF pointed out that the proposed QRs by Army HQ on a single vendor basis was based on the QRs of 1998 when the UAVs had first been procured. It did not factor in the changes in technology/upgradation which would have taken place in the interregnum nor did the QRs take into account the likely improvement in the vendor base globally.

Inordinate delay in the finalisation of Joint Staff Qualitative Requirements (JSQRs) is also an area of concern. For instance, in 2006, the three Services identified a requirement of more than 300 Medium Lift Helicopter (MLH). The JSQRs were to be conveyed to HAL as it has successfully produced ALH and has good domain knowledge and technical capability in the helicopter segment. However, even after six years, the JSQRs are yet to be finalised. The Indian Navy seems to have peeled off from the common pool. This is a typical case where the tendency is to plump for ‘Buy’ option instead of opting for either ‘Make’ or ‘Buy and Make’ option through a DPSU. HAL’s poor record in terms of delivery and quality also contributes to such a tepid response to DPSUs.

There is a clear predilection amongst the Services to look at common requirements/QRs which can be clubbed with silo mentality. A case in point is the Short Range Surface-to-Air Missile, where the Army has gone for Global RFP, while the Navy and the IAF are looking for joint D&D through DRDO, OEM (MBDA, France). So much for commonality, interoperability and cost optimality!

The primary reasons for frequent changes in QRs and their non-updation are inadequate domain knowledge and lack of adequate exposure/ experience with state-of-the-art platforms/systems. This is further queered by the lack of continuity in the job by a smattering of professionally equipped officers manning such cells. Though there is an elaborate process for approving SQRs through collegiate vetting by different agencies, experience reveals that no realistic comments or mature inputs are offered by various agencies such as DRDO, DGQA and DDP to improve upon the SQRs. Nor are they better equipped than the Service officers.

The earlier DPPs envisaged data sharing amongst the Services…

In contrast, countries such as UK and France have dedicated agencies which are responsible to formulate detailed specification. Their co-opted experts and oversight agencies also provide meaningful inputs.

The agencies in the Service HQ need to beef up their domain knowledge. The tendency to over-pitch requirements by plumping for highly futuristic technologies, brought up by glossies need to be eschewed. Even the US which accounts for nearly 46 per cent of the world’s military expenditure and 60 per cent in terms of investment of global military R&D has been going for realistic QRs for many of the upcoming platforms.

Life-Cycle Costing, Costing and Bench Marking

Most of the advanced countries resort to life-cycle costing to choose the most preferred option in acquisition as it factors in the operating cost during the life of the equipment. Typically, the airframe of a fighter aircraft has a life of 6,000 flying hours. The engine has a life of about 3,000 flying hours. The aircraft undergo periodic repair and overhaul involving spares at three levels viz. unit, intermediate and base, entailing substantial cost. Recent Life Cycle Cost (LCC) studies show that while the system acquisition cost is 28 per cent, the operational and support costs are around 72 per cent over the life span of the platform. Operational cost typically includes 67 per cent as personnel cost and 32 per cent for POL. As regards logistics support cost, labour typically accounts for 70 per cent, replenishment of spares – 20 p er cent and materials for repair around 10 per cent.

India has been buying major weapon systems, aircraft, submarines and ships which have long gestation period. In the Medium Multi Role Combat Aircraft deal, the RFP was floated in July 2007 with life-cycle costing to determine L1 duly factoring in concepts such as Mean Time Between Failure and Mean Time Between Repair. It was realistically assessed that though the upfront cost of the Russian fighters may be low, if the lifetime operational cost is taken into account, Western aircraft could be more cost-effective. It was time to eschew the hallucination that the Russian option is the least costly option!

Delay in the choice of weapons affects production programmes significantly…

It is lamentable that a similar exercise was not undertaken for the $4 billion contract like P-75 Scorpeone Submarines where subsequent follow-ons are now being contemplated. Similarly, in the case of Light Utility Helicopters, a requirement for 384 has been projected by the three Services; the LCC should have been included in the RFP. It makes eminent sense to have life-cycle costing for major platforms instead of paying through the nose for spares and ROH later on.

Costing is another area where professional expertise in the Department of Defence Production is quite inadequate. Besides, while DPSUs provide cost details, many of the OEMs are extremely chary of providing such information. The Companies Act, 1956, also does not empower the buyer to insist on costing details. Unless a provision for Access to Books is made mandatory in the RFP, element-wise cost analysis, particularly in single vendor situations, becomes well nigh impossible.

The Acquisition Wing was expected to have data base of contracts and electronic sharing of data. The earlier DPPs envisaged such data sharing amongst the Services. Surprisingly, such arrangements have now been done away with. There is, therefore, a considerable gap in knowledge regarding rates of items common to the three Services.

Benchmarking before negotiation is also a very weak area. Professional Officer Valuation is to be carried out by the Service HQ that lack good technical and costing data base. In contrast, countries like USA have a Defence Acquisition University where technical and costing experts work hand-in-hand for realistic benchmarking before price evaluation and negotiation.

Weaponisation of Platforms

Very often, delay in the choice of weapons affects production programmes significantly. A case in point is the weaponisation of the Advanced Light Helicopter. In this case, DRDO failed to meet the user’s requirements despite assurances. After it was decided that users will go for ‘Buy’ option, inordinate delay by the Army to choose the Air-to-Ground Missile has contributed significantly to delay in the delivery of weaponised ALHs. The Services cannot take a ‘holier than thou’ approach and look for scapegoats in the DPSUs, the OFs or the DRDO.

At the moment, long-term planning and investment with Indian industry lack strong government mentoring…

Further, Para 41 of Ship Building Procedure (DPP-2011) provides for nomination of a vendor by Naval Headquarters to enable standardisation. In the case of Offshore Patrol Vessels (OPVs), there has been a huge delay in delivery by the Goa Shipyard Ltd. (GSL) because of faulty nomination of vendor and lack of proper technical tie-up and expertise in delivering the Gear Box. Despite serious reservations by the Production Agency (PA), Naval HQ opted for this vendor leading to hold up in delivering of many platforms by GSL, GRSE and CSL.

While many reasons are adduced for the delayed Initial Operational Clearance for the LCA, one of the lesser known facts is the unexpected addition in weapon load not envisaged ab initio. This has also led to an inordinate delay in the selection of the propulsion system to cater for increased all-up weight and going for the same vendor viz. GE.

Long Term Planning and Industry Association

The Kelkar Committee (2005) had suggested that the Long Term Perspective Plan of the services should be shared with the industry. Although this has been agreed to, the industry associations are aggrieved that they are not involved at the Categorisation Stage during deliberation. If the defence industry, both public and private, are taken onboard while formulating the long-term requirements, this would help immensely to do a capability and capacity mapping, facilitate long term planning for capacity creation, investment and capability build up.

Presently, in cases pertaining to the Navy and the IAF, many follow-on systems and upgrades are being contemplated or being finalised. These are follow-on to P-75 [P-75(I)], P-15B, P17A(B) , SU-30 (Upgrade), FGFA and Medium Lift Helicopters. The LTIPP should firm-up the long-term requirements including follow-on requirements. It will not only bring in economies of scale but foster the process of JV arrangements with reputed OEMs and design houses. At the moment, long-term planning and investment with Indian industry lack strong government mentoring.

Another vexatious issue is assessing the reasonability of license fee for major platforms…

In terms of policy, 26 per cent cap on FDI in defence also makes the Indian defence industry an unattractive destination for long term investment unlike China which has become a major manufacturing hub for ship-building and Brazil for aircraft manufacturing, the latter permitting 76 per cent FDI in Embraer.

Transfer of Technology (TOT)

In the present dispensation, TOT can be availed of by the DPSUs/Ordnance Factories through the ‘Buy and Make’ option. Private vendors including JVs can also have TOT through the ‘Buy and Make’ (Indian) route. The new Offset Policy (2012) adds a third window as per which TOT is available through the ‘Buy’ route also.

Given these multiple options, identification of critical technology, range and depth of technology which are to be passed on and the skill upgradation required to absorb technology, become a paramount challenge in the acquisition process. It has been clearly demonstrated that the delays in technology absorption by shipyards like MDL and aircraft manufacturer HAL is due to inadequate skill upgradation.

India’s experience of license production of aircraft, ships, submarines, communication equipment and radars reveal that it has not led to any substantive improvement in design capability, value addition and manufacturing capability of major subsystems. Although TOT does not provide ‘Know Why’ but ‘Know How’ yet the defence industry gains substantive capability in manufacturing key technologies and in some measure, design capability through innovative reverse engineering. The Department of Atomic Energy has been the pioneer in reverse engineering and up-scaling design and manufacturing knowledge of reactors through technology transfer.

Modernisation and maintenance of equipment and platforms have to go hand in hand…

The multiple options for availing TOT through various routes would need to be carefully identified, calibrated and prioritised so that there is no overlap. For this, an empowered body with representatives from the Services and DPSUs would need to be constituted which would identify key technologies required, capability gaps in propulsion, weapons and sensors and how both big ticket acquisitions and license payments are best leveraged to bolster India’s military industry capability. The low Self-Reliance Quotient is attributable to complete dependence on imports for propulsion, state-of-the-art weapons, avionics and sensors of major weapons and platforms by the three services where the foreign OEMs have a field day in view of critical gaps in our design capability and DRDO’s lamentable record in design and development of critical systems such as passive seekers, focal plane array, RLG, INSGPS, Stealth, Carbon fibres, single crystal blades, propulsion systems and AESA radars.

The manufacturing capability of our DPSUs of major sub-systems and subsequent upgrades is also at low ebb as they do not invest adequately in R&D unlike China which has been able to undertake upgrades of fighter aircraft after availing of TOT unlike India which is constantly tugging at the apron strings of OEMs. The public sector behemoths in defence have become assemblers rather than significant value adders. The DRDO’s record is not too flattering either.

The DPP identifies five categories of TOT with an expectation that 30 per cent value addition is likely to be achieved by the licensee. However, realising value addition in different categories is an extremely onerous process as manufacturing capability of critical technology is rarely passed on. For instance, in the LCA programme the expectation of getting key technologies like single crystal blade and special coating for the engines has been denied by the American vendor for the GE 414 Engine.

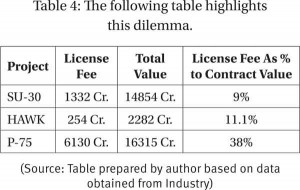

The other vexatious issue is assessing reasonability of license fee for major platforms. While the license fee has been generally of the order of about 10 per cent to contract the cost (SU-30 and HAWK aircraft) it is as high as 38 per cent in P-75 where the vendor clearly took advantage of our lack of design capability of submarines. This is despite our earlier licence-production experience of submarines.

The other vexatious issue is assessing reasonability of license fee for major platforms. While the license fee has been generally of the order of about 10 per cent to contract the cost (SU-30 and HAWK aircraft) it is as high as 38 per cent in P-75 where the vendor clearly took advantage of our lack of design capability of submarines. This is despite our earlier licence-production experience of submarines.

Level Playing Field

From time to time, the Defence Procurement Procedure has tried to bring in level playing field to the private players. DPP-2011 has been significant as it has brought in some of the ship-building contracts in the ambit of competition. However, there are areas where private players are being discriminated against, for example, the Exchange Rate Variation (ERV) which as per DPP, is available only to DPSUs. There is also a discriminatory practice in the area of giving CDE to DPSU and private players.

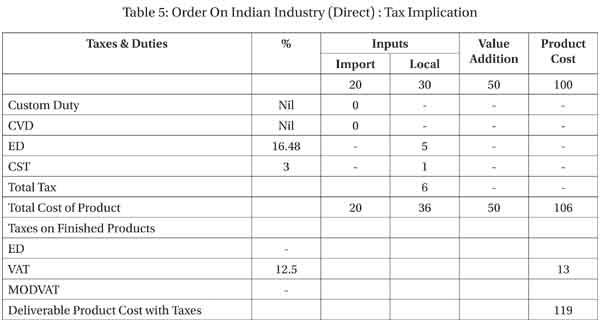

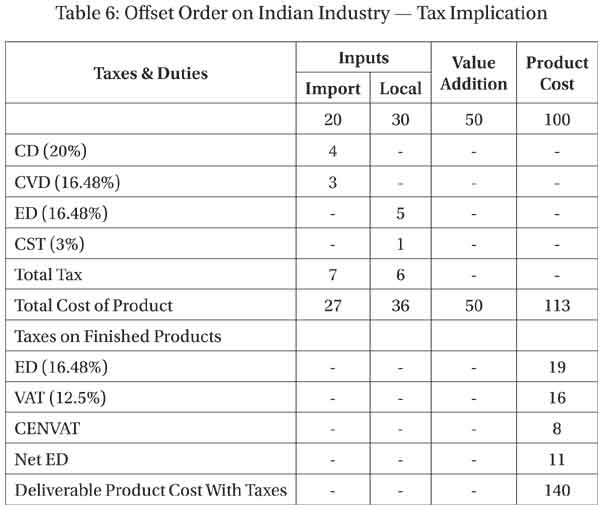

Besides, in the case of offsets also the industry feels that the benefits reduce from 30 per cent to 21 per cent because of the present taxes and duties structure. The tables below will explain the position.

The DPSUs also get financial advantage by non-furnishing or BGB/ Performance guarantee at the time of advance payment compared to the private players. It makes eminent sense that these irritants in terms of discriminatory treatment of taxes/duties for similar jobs where public private sector entities are competitors, are done away with.

Post Contract Monitoring

DPP-2011 provides for contract monitoring by Acquisition Managers for simple acquisitions and by DG Acquisition for complex procurements. There is also system of review by Secretary, Defence Production for major programmes involving licence production. This is an extremely weak area. Each agency pays only lip-service to time concerns and cost overruns. Besides, effective mid-course corrections are few and far between. There is an increasing tendency by MoD to move away from the oversight process and abdicate acquisition and Contract Management to the Services.

There is also inadequate association of domain experts in specialised areas such as costing, commercial intelligence, contract and legal issues. The expertise in MoD and MoD (Finance) is highly generalised and far from professional.

China’s experience in ship building through strong political mentorship is a major lesson for India…

The pitch is further queered by the absence of a dedicated acquisition wing with experts drawn from varied fields with long tenures unlike DGA France where both acquisition and logistics are handled under one umbrella. The Sisodia Committee (2005) had recommended an acquisition structure analogous to DGA France where R&D, trial and evaluation, acquisition and logistics are vested in one organisation. The best global practices adopted by countries like USA, France, Germany and UK follow an integrated approach with private sectors players playing the role of partners. The recommendations of the Sisodia Committee are still shrouded in secrecy. The present system also does not foster requisite jointness and inter-operability.

For major surveillance systems such as UAVs and Aerostats, each Service looks for acquisition in a stand-alone mode. This is symptomatic of a silo mentality. Not surprisingly, inter-service prioritisation remains mired in inter-service rivalry reducing CISC to being a mere collation agency for the three Services.

There is a definite need for greater professionalism in the areas of QR formulation, costing, life-cycle costing, commercial intelligence, contracting and legal nuances. The stakeholders in the acquisition wing would need to have long tenure to ensure continuity and retention of domain knowledge in specialised fields of defence.

Make Procedure

While the DPP-1992 gave primacy to indigenous R&D and production, the thrust of all DPPs is to opt for ‘Buy’ as the most preferred option. Various policy pronouncements such as the Defence Production Policy 2009 merely pay lip-service to the cause of higher indigenisation. The reason is not far to see as the ‘Make’ procedure is extremely cumbersome and dilatory. 80 per cent of the funding was supposed to be provided by the MoD to private industry for such ‘Make’ projects every year. Since 2006, a certain amount of the money has been earmarked in the MoD Budget. Ironically, this funding mechanism is yet to be operationalised. There is a clear lack of serious intent to kick-start such self-reliance initiatives.

Modernisation Maintenance Disconnect

Modernisation and maintenance of equipment and platforms have to go hand-in-hand. Acquisition cannot be separated from logistics. In the Indian defence budgeting system there is a clear disconnect between Acquisition Budgeting and Revenue (Stores Budgeting). The AAPs of the Acquisition Wing and Priority Procurement Plan of the services do not get deliberated upon in the DAC in a holistic manner. No wonder, this is seriously impeding optimal budget allocation and utilisation with recurrent clamour of higher allocation in Revenue Budget by each Service.

Conclusion

It would be seen from the foregoing that the present institutional arrangements do not lend to professional QR formulation and updation, and long-term planning and investment, optimal choice of platforms and integrated and professional functioning of Acquisition Wing are being given a short shrift. The present blame game between the Services, Ministry, DPSUs, DRDO and the private sector for the inordinate delay in acquisition has to make way for an integrated structure, where sharing of information, and partnership is ensured at each stage. The private sector has to be considered as a partner so that meaningful JVs can be forged with reputed OEMs and design houses. The long term requirements need to be shared with the industry so that they put in place requisite investment, bolster capability and R&D. Further, a major policy shift in terms of a significant mark up in FDI in defence (at least 50 per cent) is urgently called for so that India is a preferred destination for JV for reputed OEMs. The political leadership has to cut through squabble and one-upmanship between the Services, DPSUs/OFs and DRDO to ensure private-public partnership in defence. Chennai’s success story as an automobile hub and in recent times, Gujarat as an investment destination amply demonstrates this synergy. China’s experience in ship building and Brazil’s experience with Embraer through strong political mentorship should hold a major lesson for India. Else India will really slip out of BRIC!