The article Ethnic Armies was first printed in the Indian Defence Review – April-June 2000

Eleven years ago, following a coup in Fiji, leading to the overthrow of the democratically elected government of Mahendra Chaudhry, and the apparent complicity of elements of the Fijian armed forces therein, the author began a study of the ethnic dynamic at play in the armed forces of his native Trinidad, the neighbouring country of Guyana and Fiji.

Fiji has effectively excluded Indo-Fijians from national political leadership while in Guyana racial vitriol is never far from the political diatribe launched against the government which is supported by Indo-Guyanese.

Since the original article much has changed. Trinidad has had no fewer than five General Elections, culminating in the election of the country’s first female Prime Minister, Mrs. Kamla Persad-Bissessar, a Hindu Indo-Trinidadian. Guyana’s President Bharrat Jagdeo is demitting office with elections due in late 2011. Fiji is now under a de facto military dictatorship that has, rather surprisingly, acted to assuage at least some apprehensions of the Indo-Fijian population and to act against some of the grosser abuses perpetrated by the native Fijian population. Furthermore, recently, Guyana’s Disciplined Forces Commission has had its report finally approved by the country’s parliament and an unseemly row over ethnic representation in the Trinidad and Tobago’s Police Service led to the dismissal of the Indo-Trinidadian Chairman of the Police Service Commission.

It needs to be reiterated that the Indians of Fiji, Guyana and Trinidad are now largely third-generation migrants, having been brought as indentured labourers to work on sugar plantations. This labour importation took place between 1834 and 1917. Indo-Fijians, Guyanese and Trinidadians are all citizens of their respective countries. Furthermore, in numerical terms, Indians comprise very substantial proportions of the populations in these nations – ranging from 40% in Trinidad, to 43.5% in Guyana, to 37.6% in Fiji. Indians represent the largest racial grouping in both Trinidad and Guyana but while Indo-Fijians comprised over 45% of Fiji’s population in the late 1980s, massive emigration had dramatically reduced their numbers.

Politically, Fiji has effectively excluded Indo-Fijians from national political leadership while in Guyana racial vitriol is never far from the political diatribe launched against the government which is supported by Indo-Guyanese. Trinidad is, as always, more complicated with racial factors clearly playing a role in politics but with the current Indo-Trinidadian prime minister enjoying considerable support across ethnic lines but having significantly lower support among non-Indo-Trinidadians and with a much lower level. Racial tension in Trinidad is much lower than in either of the other two subject countries and relations between the two main ethnic groups – African and Indian – are generally harmonious.

This article is not intended to be a rehash of the data, or the conclusions contained in the original. Rather it is to provide an update on the situation as it relates to the ethnic composition of the security forces in the subject countries.

Fiji

In October 2007, the Republic of Fiji Military Forces finally revealed details of its ethnic composition. The data, however, was worse than expected – of 3527 full-time personnel only 15 were Indo-Fijian.1 This represents a ludicrously low 0.425% of the military establishment.

Despite his purported desire to end racial strife and discrimination, Commodore Bainimaramas choice as Fijis Police Commissioner led to a major incident of racial and religious tension.

These figures represent a massive deterioration in the representation of Indo-Fijians, who even in 1975 contributed 36 members of the 1030 strong military forces.2 It would therefore appear that factors other than the usual excuse of rigours physical standards deterring Indians are at play. The participation of the military in each of the successful armed overthrows of Fijian governments almost certainly has served to deter Indo-Fijians from enlisting in an outfit that has repeatedly shown itself to be biased in its dealings with the community.3

The current military dictatorship of Commodore Voreqe (Frank) Bainimarama has openly expressed a desire to move away from the existing communal electoral rolls which are heavily biased in favour of the indigenous population to a single common electoral roll and has advocated a policy that moves away from special rights and protection to the indigenous Fijian population. However, his regime has not moved decisively to end the de facto exclusion of Indo-Fijians from the armed forces and his regime’s failure to hold elections is cause for major concern.

Despite his purported desire to end racial strife and discrimination, Commodore Bainimarama’s choice as Fiji’s Police Commissioner led to a major incident of racial and religious tension. Commodore Esala Teleni embarked upon a Christian crusade within the Fijian Police Force and openly encouraged and/or forced Indo-Fijian police officers, the vast majority of whom are Hindu or Muslim to participate. In an unprecedented display of bigotry, Teleni called Indo-Fijian officers “backstabbers and liar” and issued thinly-veiled threats of dismissal.4 Commodore Bainimarama’s apparent support for these comments was inexplicable.5 However Teleni “resigned” as Police Commissioner in August 2010.6

There have been recent signs that more Indo-Guyanese are coming forward to join the GPF with anecdotal evidence suggesting that near parity in recruiting numbers has been achieved on occasion.

It would appear that the Fijian police, once a majority Indo-Fijian outfit, have also suffered a decline in Indo-Fijian representation. Though the Fijian police claim to closely represent the ethnic composition of the population, it would appear that at most 30% of the Fijian police are of Indian descent – a sharp drop from 45.5% in 1984.7

It is difficult to determine what the future holds for the Indo-Fijian population, much less its composition of the protective services of that nation. That the political discourse in Fiji degenerates so easily into racially exclusivist and racially supremacist language on the part of indigenous Fijian politicians is a damning indictment on that country and such attitudes are incompatible with civilized countries in the 21st century.

Guyana

In May 2004, Guyana’s Disciplined Forces Commission submitted its final report a year after being constituted. The Commission’s report dealt with inter alia measures to increase the efficacy of the Disciplined Forces as well as addressing the ethnic imbalance issue that has long plagued the Guyanese protective services. Of particular interest to the subject at hand were the details released on the ethnic composition of the Guyana Defence Force (GDF) and the Guyana Police Force (GPF).

In testimony before the Commission, the GDF indicated that it had, in 2003, an actual strength of some 2630 personnel – 20 short of its authorised strength. Of these 80% were Afro-Guyanese, 8% Indo-Guyanese and 12% of other races.8

The GPF was considerably less forthcoming with raw data about its composition and the Commission was forced into accepting an observation that the 2750 strong GPF seemed to have a ratio of 1 Indo-Guyanese officer to 5 non-Indo-Guyanese.9

| Editor’s Pick |

If this data is accurate, and there is no indication to the contrary, then there has been a marked deterioration in the representation of Indo-Guyanese in the GDF and GPF. The facts disclosed reveal a situation that is even worse than that which existed in 1965.

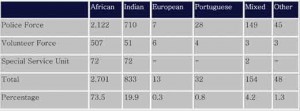

It may be recalled that in 1965, the International Commission of Jurists conducted an inquiry in which, among other things, the question of racial balance in the security forces was addressed. Their findings, especially in light of the data disclosed above make for sobering reading and indicate that Indians made up only 19.9% of the total security forces:10

The data thus disclosed to the Commission indicates that the years of rule by the Afro-Guyanese dominated PNC intensified a pattern of de facto exclusion of Indo-Guyanese from the protective services. The GPF in particular seems to have suffered heavily in this regard as its Indo-Guyanese component fell from 23% in 1965 to less than 17% at present. The data for the GDF would seem to indicate that enlistment patterns have remained substantially the same for the last several decades.

What is truly astonishing is that the aforementioned figure of 17% may actually represent a substantial improvement in the ethnic composition of the GPF as a study of empirical recruiting data by G.K. Danns between the years 1970 and 1977 shows that fewer than 7.8% of the recruits during that period were Indo-Guyanese, this perhaps being a consequence of a deliberate policy of biased recruiting undertaken by the quasi-dictatorships of Forbes Burnham and Desmond Hoyte:11

There have been recent signs that more Indo-Guyanese are coming forward to join the GPF with anecdotal evidence suggesting that near parity in recruiting numbers has been achieved on occasion. The Disciplined Forces Commission was not in favour of racial quotas in recruiting calling them “constitutionally offensive” but nonetheless supported moves towards greater inclusivity and to establish an effective grievance redress mechanism for Indo-Guyanese recruits and officers who may feel unfairly targeted on racial grounds.12 The increased proportion of Indo-Guyanese recruits, however, gives lie to the assertion of a lack of willingness on the part of Indo-Guyanese to join the GPF. While there is no direct linkage between the ouster of the PNC from power in 1992, it would appear that the PPP Government has been supportive of a much more inclusive and racially balanced recruiting policy than its rival.

The GDF presents a somewhat different scenario with Indo-Guyanese representation therein remaining static for a considerable period of time. To the credit of the GDF it very openly stated to the Commission that:13

- At any rate, the question of ethnic balance in the GDF is a reality which needs to be addressed, and

- Admittedly, the GDF policy, allowing for all ethnic groups to join its ranks is not well known and should be widely advertised as part of allaying any perceived security fears.

Such admissions are undoubtedly to be commended but it remains to be seen whether or not the GDF will take the initiative in facilitating a change in perception among Indo-Guyanese, thus perhaps enabling greater enlistment amongst that group.

The precedent set by the misuse of security forces in Fiji and Guyana has unfortunately skewed the perception of the security forces in all three nations under review.

Trinidad and Tobago

One of the major differences between Trinidad and Tobago and the other two nations under review is that the tensions between the two major ethnic groups have not involved the armed forces or the police. The Trinidad and Tobago Police Service (TTPS) and the Trinidad and Tobago Defence Force (TTDF) have not participated in any of the political pogroms that have plagued both Fiji and Guyana. Indeed any concerns about the racial composition of the TTDF and the TTPS are born out of the fear that the said forces could become instruments of ethnic repression rather than on any tangible evidence of any such tendencies.

Unfortunately, discussion of racial issues in the country often leads to arguments and accusations rather than reasoned debate and an attempt to raise the issue regarding the TTPS led to the dismissal in 2011 of the head of the Police Service Commission, Mr. Nizam Mohammed. It is this immaturity that has masked some tangible progress made by the TTPS and has also served to conceal some areas of possible concern.

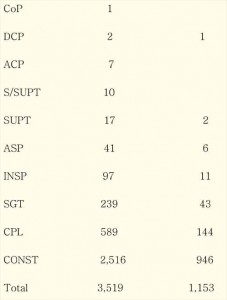

Indo-Trinidadians have traditionally been significantly better represented in the TTPS than in the TTDF. In 1992, the TTPS was composed as follows:

The said totals show that as of 14 September 1992, the TTPS had an Indo-Trinidadian component representing some 24.67% of the force.14 As can be seen, however, the proportion of Indo-Trinidadians decreases substantially above the rank of coroporal.This trend has unfortunately continued with data from 2010 revealing that there were no Indo-Trinidadians above the rank of Superintendent. This was despite Indo-Trinidadians now comprising 1917 of the 6219 strong TTPS – 30.82%. According to the data thus revealed:15

“As of December 2010, Africans accounted for ten Assistant Commissioners of Police, 15 Senior Superintendents, 21 Superintendents, 33 acting superintendents, 108 inspectors, 303 sergeants, 488 corporals and 2,860 constables. A breakdown of the East Indian composition included ten Superintendents, ten acting superintendents, 42 inspectors, 158 sergeants, 377 corporals and 1,320 constables. The statistics further revealed there are no East Indians in the ranks of ACP and Senior Superintendent. A third category – Mixed – accounted for 464 officers. In this category, five are senior superintendents, four superintendents, four acting superintendents, six inspectors, 20 sergeants, 100 corporals and 325 constables.”

It is interesting to note that the percentage of Indo-Trinidadian constables – 29.33% is lower than the overall Indo-Trinidadian component in the TTPS. This cannot be reasonably attributed to racial discrimination. Rather the cause is more prosaic – the TTPS embarked upon a substantial increase in its female component and in that category fewer than 10% of recruits are Indo-Trinidadian. This is not the case for male recruits where in one batch in 2010, 21 out of 40 of potential recruits were Indo-Trinidadian.16 However, there are serious concerns regarding the fairness of the promotions process with the suggestion being made that a certain degree of racial discrimination exists at the promotion stage. A recommendation to abolish the Promotion Advisory Board of the TTPS has not been implemented to date.17 Such discrimination, if proven, is clearly unacceptable and needs to be investigated without delay.

The situation in the TTDF is rather different. Indeed, there are signs that the ethnic imbalance – never good at the best of times – has dramatically worsened since 1992. It must be stated, however, it is very unclear whether this is as a result of racial discrimination and any suggestion to that effect is perhaps premature.

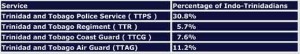

In 1992, the TTDF comprised of the Trinidad and Tobago Regiment (TTR) and the Trinidad and Tobago Coast Guard (TTCG). In that year, the ethnic balance was given as follows:18

Since then, the TTDF has been substantially expanded in size – more than doubling in the case of the TTR (to brigade size with four battalions and 2900 personnel) and the TTCG (to over 1300 personnel) and the formation of a small independent air wing (the Trinidad and Tobago Air Guard TTAG with 196 personnel) in 2005. However, the ethnic composition of the forces has shown a marked deterioration:19

This apparent deterioration in the proportion of Indo-Trinidadians in the TTDF may be at least partially due to the overstating of the 1992 data by the inadvertent inclusion of mixed-race personnel in the data for Indo-Trinidadians.

Nonetheless the decline should be cause for concern as, while the TTDF asserts with some justification that it does not discriminate against Indo-Trinidadians, there is a perception that the TTDF does not want Indo-Trinidadian recruits and that during the course of training, Indo-Trinidadian recruits are singled out for racial abuse by Afro-Trinidadian recruits and NCOs. There is some evidence to suggest that such abuse may indeed occur but such instances are exceptions rather than the norm.20 There seem, however, to be few bars to promotion within the TTDF as both the TTR and TTCG have had Indo-Trinidadian Commanding Officers and the current Chief of Defence Staff is also Indo-Trinidadian.

However, there is also a general reluctance among Indo-Trinidadians to enlist in the TTDF, partly because of better career opportunities elsewhere, but also because of a complete lack of awareness of the career options available in the TTDF. So thorough is the disconnect between TTDF recruiting efforts and the Indo-Trinidadian community that few of the latter even know when recruiting takes place. With no military presence in Indo-Trinidadian dominated areas, members of the community are not exposed to the military and as a result few have any interest in enlisting. This state of affairs is not satisfactory as a disproportionate share of Trinidad’s skilled and educated manpower is thus effectively excluded from TTDF selection.

Conclusions

The precedent set by the misuse of security forces in Fiji and Guyana has unfortunately skewed the perception of the security forces in all three nations under review. This is doubly unfortunate in that in Guyana and Trinidad there are opportunities for the Indo-Trinidadian community to rectify historical imbalances and by so doing remove the risk of such forces being used for ethnic repression in the future. Racial discrimination may be a factor but in the latter two cases at least, the principal factor in poor Indian representation in the security forces is a lack of applicants. It would be a pity if this trend continues.

Notes:

- "Rumblings of a revolution", Hamish McDonald, Sydney Morning Herald, October 27, 2007

- R. Premdas, Ethnic Conflict and Development: The Case of Fiji (Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing, 1995), p.32

- The term Indo-Fijian as used here has met with opposition from some indigenous Fijian politicians who claim that the term “India” should be used as the term Indo-Fijian undermined the supremacy of the indigenous population. See "Ban the term Indo-Fijian: Minister", Hindustan Times, August 5, 2006

- http://www.stuff.co.nz/world/1404533/Fiji-police-chief-attacks-Indian-police-officers

- http://www.solomontimes.com/news.aspx?nwID=3616

- http://www.radiofiji.com.fj/fullstory.php?id=30289

- V. Lal, Fiji: Coups in Paradise (New Delhi: Allied Publishers, 1990), pp.27-28 and Y. Gaunder, 'Island's Curse' in India Today: June 5, 2000

- Unofficial pdf copy of the Disciplined Forces Commission Report: May 2004, p.196

- Ibid, p.89

- Report of the British Guiana Commission of Inquiry, p.49

- G. K. Danns, Domination and Power in Guyana (New Brunswick: Transaction Books, 1982 ) pp.120-122

- Unofficial pdf copy of the Disciplined Forces Commission Report: May 2004, pp.90-101

- Ibid p.200

- S. Ryan & J. La Guerre, Ethnicity and Employment Practices in Trinidad and Tobago (St. Augustine: Centre for Ethnic Studies, 1993), p.160. It should be noted however, that this study did not adequately address the “mixed-race” phenomenon in Trinidad. It is likely that the Indo-Trinidadian percentage was at the time slightly lower than the numbers suggest.

- http://www.trinidadexpress.com/news/Gibbs__Khan__Nizam_talking_for_months_on_imbalance-119161194.html

- This was taken from a list of potential recruits published in the local media in May 2010. Anecdotal evidence suggests up to 42% of police recruits in 2009 were Indo-Trinidadian.

- http://www.guardian.co.tt/node/10070

- Data taken from Ethnicity and Employment Practices in Trinidad and Tobago

- While the TTPS data is official, the information for the various branches of the TTDF is based on the author’s discussions with TTDF personnel conversant with the figures.

- The author has heard of at least two such instances – one first hand from a retired officer in the TTR and the other second hand from a physician who treated the victim of such abuse.