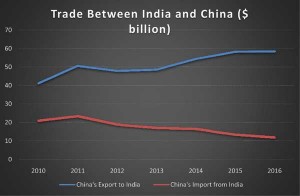

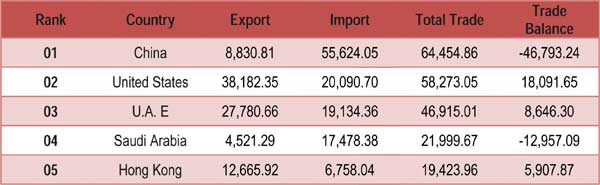

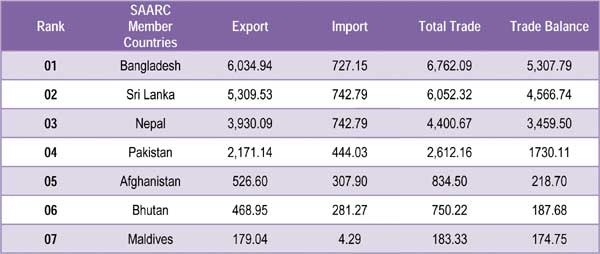

As for international politics, international trade has nothing personal about it. While India may have earned the entitlement of a rising power in some quarters of projected strategic imagination, facts express a dim picture. India’s total trade (2016-17) with its immediate neighbours minus China remains miniscule when compared with China which is India’s largest trading partner followed by United States. Members of SAARC do not figure in top 25 trading partners of India making South Asia the world’s least economically integrated regions of the world.

Year: 2016-2017 (Apr–Feb), Values in US$ Million Department of Commerce: Export Import Data Bank (India’s Total Trade-Top Five Countries)1

Over the past decade, China has become a significant economic partner to SAARC member countries, forging particularly strong ties with smaller states through trade, diplomacy, aid, and investment, which has the potential to challenge India’s traditional role in the South Asian regional order[1].However, India still retains strategic advantage in SAARC member nations minus Pakistan which has extra-ordinary strategic relationship with China. However, such an advantage for India is fast eroding in the wake of China’s growing potential economic influence in the region. Sri Lanka which shares a significant relationship with India has now slowly drifted towards China which has improved its relationship with the island nation since the out-break of civil war in 2009 which peaked in 2011.

Year 2016, Values in US$ Million, Department of Commerce: Export Import Data Bank (India’s Total Trade-SAARC Member Countries)2

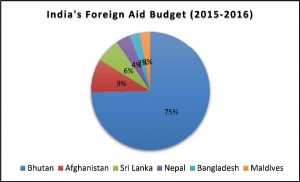

Between 2012 and 2015, China disbursed almost $2.5 billion, of which more than 75 percent came from the Export-Import Bank of China and the Sino-Sri Lankan relationship was upgraded to “Strategic Cooperative Partnership” in 2013. During the same period, India extended $660 million in lines of credit[2].However, despite similar developments in Bangladesh and Nepal, India’s cultural ties born out of civilizational linkages and geographical proximity within the region remain intact and likely to remain so in near-long term. For example, remittances from Indian migrant workers stood at $ 9 billion in the region compared to China’s $ 1 billion of which $ 958 million came from Chinese workers in Bangladesh alone[3].

India too has in the past decade stepped up its efforts at investing, providing foreign aid and improving its trade relations with its neighbors in South Asia. During 2009-10, India provided US$ 383.01 million in aid and loans to South Asian countries (except Pakistan), which has expanded to US$ 1,149 million in 2015-16[4].

Despite India’s expanding investments abroad, in comparison it remains less significant in value. According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development’s World Investment Report (2016) India does not figure in the top 20 economies with FDI outflows[5]. China along with US and Japan remain among the top five investing economies. In Asia, the top investing economies in 2014 remain China (FDI stock $ 513 billion) followed by US ($ 430 billion) and Japan ($ 414 billion). Four of the top ten investor economies in Asia are extra-regional (US, UK, Germany and France), the remaining are from Asia itself[6]. The largest recipient of FDI in Asia are Hong Kong, China ($174.9 billion), China ($135.6 billion), Singapore ($ 65.3 billion), India ($44.2 billion), and Turkey ($ 16.5 billion)[7].

Despite India’s expanding investments abroad, in comparison it remains less significant in value. According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development’s World Investment Report (2016) India does not figure in the top 20 economies with FDI outflows[5]. China along with US and Japan remain among the top five investing economies. In Asia, the top investing economies in 2014 remain China (FDI stock $ 513 billion) followed by US ($ 430 billion) and Japan ($ 414 billion). Four of the top ten investor economies in Asia are extra-regional (US, UK, Germany and France), the remaining are from Asia itself[6]. The largest recipient of FDI in Asia are Hong Kong, China ($174.9 billion), China ($135.6 billion), Singapore ($ 65.3 billion), India ($44.2 billion), and Turkey ($ 16.5 billion)[7].

India occupies the eighth position among the top investing economies in Africa in 2014 with $15 billion of FDI stock. The largest investors in Africa were UK ($ 66 billion), US ($64 billion), France ($ 52 billion) and China ($ 32 billion). The largest recipients of investments in Africa are Angola ($8.7 billion), Egypt ($6.9 billion), Mozambique ($3.7 billion), and Morocco and Ghana ($ 3.2 billion). Expect for South Africa, all major investors are extra-regional powers[8]. Nigeria and Libya have emerged as investment destinations in 2015.Both India and China do not figure in top investing economies in developed nations (2014), however Japan does at seventh position. US ($ 2031 billion), UK ($ 1360 billion), France ($856 billion), Germany ($820 billion), Netherlands ($ 780 billion) and Switzerland ($720 billion) are the major investors. The major recipients are United States ($ 379.9 billion), Ireland ($100.5 billion), Netherlands ($72.6 billion), Switzerland ($ 68.8 billion), and Canada ($48.6 billion). In least developed economies China is the top foreign investor ($ 27 billion) in 2014 followed by US ($ 9 billion), and Norway and Republic of Korea ($ 6 billion)[9].

India’s contribution to least developed economies remains insignificant. Since it launched reforms and opening up, China has attracted over $1.7 trillion of foreign investment and made over $1.2 trillion of direct outbound development[10]. For the future according to President Xi Jinping in next five years China is expected to import $8 trillion of goods, attract $600 billion of foreign investment and make $ 750 billion of outbound investment.

In analysis, developed nations invest in developed economies, Asia and Africa, however the proportion of investment in advanced economies in much higher compared to investments in Asia and Africa. Unlike Africa which relies on investment from extra-regional powers, Asia’s investments largely come from Asia, however extra-regional powers do invest in Asian economies. The current investment values are less significant compared to the required investments in Asian economies which according to some estimates is approximately $14 trillion required by energy, social, educational and infrastructural sectors. Sanitation alone is likely to be a source for major investments in Asian economies given its population size.

Statistical analysis of any phenomenon is a murky affair, like a lady’s short skirt which reveals what’s important but hides what is vital. A comparison of international trade in goods reveals a comparative advantage in favour of China given its positive balance of trade vis-a-vis India, United States, and United Kingdom who have a negative balance of trade. However, when taken into account the quality of the goods being traded China may not have such an advantage. For example, while China’s top exported good remains electrical machinery and equipment and parts thereof along with machinery, mechanical appliances, nuclear reactors and boilers thereof, for United States it is aircraft, spacecraft and parts thereof along with machinery, mechanical appliances, nuclear reactors and boilers thereof.

China further imports mineral fuels, mineral oils, and products of their distillation to the extent that United States does not. For U.S. mineral fuels are fifth most exported commodity in 2016. In between US, China, UK, and India – US is the largest importer of goods along with largest negative trade balance where as China is the largest exporter along with largest positive trade balance. However, China’s exports are dependent on high-technology imports that are used to process further exports such as electronics which shares 50.4% (2012) of all of China’s processing exports. Its ordinary exports remain textile which constitutes 24.8 % (2012) of the total ordinary exports[11].

For India, whose largest exported commodity is natural or cultured pearls, precious or semi-precious stones, precious metals share its largest negative trade balance with China (-46,793.24 US$ million) and largest positive trade balance with US (18,091.65 US$ million). India’s economic potential remains bleak not just in Sino-Indian context but also within the context of BRICS where India happens to be the weakest link.India shares the highest percentage of primary industry among BRICS grouping members at 25.7 per cent of the GDP in 2000 and 20.5 per cent in 2013 compared with Russia at 4.0 per cent, Brazil at 5.7 per cent and China at 10 per cent in 2013[12].

The United States is the largest economy in the world with a GDP of $18trillion. China is the world’s second largest economy with a GDP of $11 trillion. Meanwhile, the United States is the largest developed country, with its per-capita GDP reaching $50,000, and China is the largest developing country, with its per-capita GDP reaching $8,000. The average per-capita GDP is $11,000 worldwide. The volume of Sino-US bilateral trade was over $500 billion in 2016, the highest bilateral investment figure in the world[13]. The GDP per capita in India was 1751.70 US dollars in 2015, the highest for an average GDP per capita of 654.70 between 1960-2015[14]. The GDP per Capita in India is equivalent to only 14 percent of the world’s average.

It is quite evident from the above comparison that China’s has a unique position when compared with India to contemplate and execute a major initiative such that of OBOR which is not limited to the material capability alone but a grand strategy that interprets its intent and therefore providing an acceptable rationale for its execution at such a grand scale. The strategic consequence associated with OBOR which spills over to the security domain requires subtle clarification. In theory, with investments made into a particular economy, political influence is expected to follow that may alter the existing strategic balance. However, such a reality has not unfolded in Africa, South East Asia, and elsewhere in Central Asia. The logic of international politics continues despite economic interferences.

For example, China’s investments in Gwadar or Colombo and Hambantota transforming into a strategic asset is not dependent on the economic investments alone, the political relationship will remain significant despite investments. Sri Lanka in the recent past has factored in India’s sensitiveness with respect China’s submarines docking at its port facility[15] and Pakistan is likely to factor in US concerns prior to allowing its territory to be used by a third power such as China. There are limitations to which economic transaction may convert itself to political influence. It’s a complex equation and not a simple straight jacket, however it does not allow space for complacency. Iraq and Afghanistan where the western powers invested heavily to institute and develop democratic political system has not ended up to their advantage or allow for significant political influence.

In Afghanistan Taliban will remain central to its political evolution and Iraq will exercise its national interest despite decade long western investments only to reengage its erstwhile military supplier Russia. Hence “Politics is Politics” and economic interference has a limited value in shaping the political realities in which strategic decision is likely to be made. For India, China is her largest trading partner with huge trade deficit in favour of China, does that mean India is likely to follow Chinese dictum at the cost of her national interest? The simple answer is no. India has trained Afghan civilian and security leadership in India and incurred high value investments, does that mean Afghanistan is likely to accept all of Indian requests without factoring in its national and domestic interests? The simple answer in no.

Therefore, in order to understand the strategic implications of OBOR within the Sino-Indian context an analysis must transcend the numeric of trade and investment and focus itself on china’s strategic thought that synthesise its grand strategy in long-term. If at all India needs to consider the strategic consequences of OBOR to its national security, the framework of analysis must be designed within a long-term perspective. The most adverse strategic consequence is likely to be the expansion of strategic optional base for countries that will be part of OBOR in South Asia, Central Asia, South East Asia and Eastern Europe who will now have China as part of their strategic equation vis-à-vis other regional powers. This will and should be the prime concern for Indian policy makers in long-term.

For example, in South-East Asia where China emerged as the largest trading partner since it initiated a strategic rethink in 1993 at the behest of former Foreign Minister Qian Qichen’s advice after the Southern Tour, United States remains an important source of security[16]. Economic interdependence has certainly altered the erstwhile strategic balance of power in South East Asia but has not yet culminated into region where China can exercise its free will, instead the equation is far complex.

The following section therefore looks at the reasoning behind OBOR as a grand strategy to address China’s discomfort with the in-vogue economic order in order to identify the possible strategic intent behind OBOR.

China’s Quest for a New World Economic Order

Gauging within the framework of OBOR, since the 2008 financial crisis China’s foreign trade has continued to grow faster that international trade by relocating itself as a “normal” foreign trade system integrated with its domestic economy[17]. In other words, China is moving away from an export oriented economy like Germany, to a consumption oriented economy like United States. OBOR as a strategic framework is designed to regulate to the extent possible the disappearing external conditions that favoured China’s extraordinary rise in world trade for two decades along with structural changes taking place within China’s domestic economy[18]. However according to Francoise Lemoine and Deniz Unal, for China processing activities have declined rapidly while China’s ordinary trade, driven by domestic demand and indigenous capabilities, has emerged as the most dynamic constituent of its international trade[19].According to President Xi Jinping household consumption and the services sector have become the main drivers of growth. Along with the strategic need to balance China’s internal and external dimensions of its world trade, China is now emerging as an international monetary power[20].

In other words, China’s Renminbi has the potential qualities to emerge as the leading reserve currency to facilitate international trade. However, China has claimed that it has no intention to boost its trade competitiveness by devaluating the yuan, still less will it launch a currency war[21].

Of the term “globalisation” China adheres only to the aspects of “economic globalisation” vis-à-vis “political globalisation” as perceived in a western context. China does not believe economic globalisation to be the cause of refugee crisis in Middle East or North Africa along with the international financial crisis, however China does consider economic globalisation as a double-edged sword.[22]The refugee crisis in Middle East, Europe and North Africa according to Chinese reasoning is war, conflict and regional turbulence and its solution lies in making peace, promoting reconciliation and restoring stability. Global financial crisis on the other hand have been reasoned as a consequence of excessive chase of profit by financial capital and failure of financial regulation.

According to President Xi Jinping (Davos, 2017), from a historical perspective, economic globalisation resulted from growing social productivity, and is a natural outcome of scientific and technological progress, not something created by individuals or any countries. Furthermore, economic globalisation has powered global growth and facilitated movement of goods and capital, advances in science, technology and civilization, and interactions among peoples. Despite having overcome the fears of economic globalisation, while China now believes it has learnt to swim in the global economy it fears any attempt to cut off the flow of capital, technologies, products, industries and people between economies, and channel the waters in the ocean back into isolated lakes and creeks is simply not possible. This according to President Xi Jinping runs counter to the historical trend. Three major critical issues yet to be addressed in the economic sphere are as following;

• The growth of the global economy is now at its slowest pace in seven years. Growth of global trade has been slower than global GDP growth. Global economy lack new drivers of growth (such as 3D printing, and Artificial Intelligence) since tradition drivers are now weakened.

• Inadequate global economic governance makes it difficult to adapt to new developments in the global economy. The fact that 80% of growth of global economy comes from developing countries, however global governance system does not reflect this reality and hence inadequate in terms of representation and inclusiveness.

• The richest 1% of the world’s population own more wealth than the remaining 99%. Over 700 million people in the world are still living in extreme poverty. Inequality in income distribution and uneven development space are worrying.

With a view to resolve such issues, China seeks an innovation led economic model based on super national interest which is sought not at the expense of others national interest and redouble efforts to develop global connectivity to enable all countries to achieve inter-connected growth and share prosperity. China considers reforming of the global economic governance system a pressing task for the international community by adapting to new dynamics in the international economic architecture through which the global governance system can sustain global growth. Bottom line being China would not like the continuation of a world order where in one can select or bend rules as one sees fit (2010 IMF and The Paris Agreement).

In his address at the United Nations Office at Geneva on 18 January, 2017 President Xi Jinping articulated the following important points significant to Sino-Indian relations and inter-national relations in particular[23];

• The idea of sovereign equality was the most important norm governing state-to-state relations over the past centuries. The essence of sovereign equality is that the sovereignty and dignity of all countries, whether big or small, strong or weak, rich or poor, must be respected, their internal affairs allow no interference and they have the right to independently choose their social system and development path.

• Advance democracy in international relations and reject dominance by just one or several countries.

• All countries should jointly shape the future of the world, write international rules, manage global affairs and ensure that development outcomes are shared by all.

• Countries should foster partnerships based on dialogue, non-confrontation and non-alliance.

• Major Powers should respect each other’s core interests and major concerns, keep their difference under control and build a new model of relations featuring non-conflict, non-confrontation, mutual respect and win-win cooperation.

• Big countries should treat smaller ones as equals instead of acting as a hegemon imposing their will on others.

• No country in the world can enjoy absolute security.

• China will never waver in its pursuit of peaceful development. No matter how strong its economy grows, China will never seek hegemony, expansion or sphere of influence.

Analysed in terms strategic thought, the above summary of President Xi Jinping’s speech reveals; (1) China seeks changes to the in-vogue aspects of world economic order (2) It has learnt that in the past nations have adopted incorrect approaches to attempt changes to the economic order by positioning themselves in a conflictual relation with each other, China wishes to avoid such an approach (e.g., Germany and Japan in mid-20th century) guided by its doctrine of peaceful rise (3)In order to secure policies such that of OBOR, China guided by its traditional strategic thinking is positioning itself to success by pre-arranging or setting up the scenario for assured success and adaptation to unexpected uncertainties (4) OBOR, and ideas associated with Chinese Dream have maximum spatial and temporal dimensions. Both seek to address global dimensions of its national narrative within a long-term perspective which begins around the time when Chinese held 30 % share of global GDP.

While China’s OBOR initiative has aroused curiosity in terms of its true strategic intent, its overall implication was expected from China, the second largest economy of the world. The concept of G-2 put forward by former US Assistant Secretary for International Affairs of the US Treasury given China’s appearance as a free rider whose economic rise was as much external as internal expects China to put forward policies where in incurs costs associated with the world economic order[24]. Chinese leadership has agreed that after 30 years of successful economic reforms China was ready to give back to world its economic achievements. According to President Xi Jinping (2017) China will do well only when the world does well.

Conclusion:

The fact that only 28 Heads of State attended the OBOR Forum held at Beijing on May14-15, and major economic powers Germany, France, India, US and UK chose not to represent at the highest level suggests continuation of real-politick. However, this does not take away the theoretical merits of OBOR initiative which seems to deeply reflected by China in strategic terms when the UN General Assembly, the UN Security Council, UNESCAP, APEC, ASEM and the GMS have all incorporated or reflected Belt and Road cooperation in their relevant resolutions and documents. The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and Silk Road Fund[25] have provided firm support to financial cooperation[26]. Apart from its execution, in terms of an idea OBOR remains a master stroke where China has let go of its unilateral stakes in the project by allowing for strategic partnership is both economic and security spheres.

For India, OBOR will remain both a challenge and opportunity depending how India develops its economy in near-long term. Trade deficit with its largest trading partner by volume and lack of intra-regional trade in its immediate neighbourhood will remain cause for concern.

Despite the challenges offered by OBOR in South Asia which may increase China’s political and economic influence in the region, India has begun the process of investing in its immediate neighbours and developing strategic partnership with extra-regional powers to deal with the unexpected uncertainties. What remains central to India is its partnership with China in coming years. While India and China are the key drivers of world GDP growth amidst financial instability, the potential of their bilateral trade relations is far from optimal, instead it is underperforming. Initiatives of BRICS, New Development Bank, and ASEAN led initiative of Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP)where in India and China have expressed strategic alignment is likely to develop Sino-Indian trade relations further by building on each other’s domestic economic advantages and allow India to integrate with Asia-Pacific region and China with South Asia[27].

RCEP according to Asian Development Bank (ADB) will accelerate China and India’s GDP by 1.45 percent and 1.74 percent respectively. However according toChina’s Ministry of Commerce, in 2015 China’s direct investment in India was $ 3.77 billion which is 0.34 percent of total FDI received by India and 1.34 percent of China’s total FDI abroad. India’s total investment in China was only $313 million in 2014, accounting for 0.34 percent of its total FDI abroad and 1.34 percent of total FDI received by India (International Monetary Fund)[28]. In economic dimension OBOR is less likely to cause negative consequences for India and China bilateral relations as both stand to gain from each other’s economic growth and development.

“Our real enemy is not the neighbouring country; it is hunger, poverty, ignorance, superstition and prejudice.” (The Founder of the Red Cross Henry Dunant cited by President Xi Jinping at Davos – January, 2017)

Having outlined the economic dimensions of OBOR in Sino-Indian context, the final (Part III) analysis will attempt to decode the military security aspect of OBOR within the Sino-Indian Context and clarify its traditional security dimension.

Reference:

[1]Ashlyn Anderson and Alyssa Ayres (2015), “Economics of Influence: China and India in South Asia” Council on Foreign Relations (Experts Brief), 03 August. Available at https://www.cfr.org/expert-brief/economics-influence-china-and-india-south-asia

[2]Ashlyn Anderson and Alyssa Ayres (2015), “Economics of Influence: China and India in South Asia” Council on Foreign Relations (Experts Brief), 03 August. Available at https://www.cfr.org/expert-brief/economics-influence-china-and-india-south-asia[Accessed on 22 May, 2017]

[3]Ibid;

[4]PreetiBhogal (2016), “The Politics of India’s Foreign Aid to South Asia”Global Policy, 07 November, 2016. Available at http://www.globalpolicyjournal.com/blog/07/11/2016/politics-india%E2%80%99s-foreign-aid-south-asia[Accessed on 22 May, 2017].

[5]The top five economies with most FDI outflows are – US, Japan, China, Netherlands and Ireland. Oindrila Sarkar (2017), “India’s Investment Abroad Soars, But Still Behind China”New Indian Express, 27 January, 2017. Available at http://www.newindianexpress.com/business/2017/jan/27/indias-investment-abroad-soars-but-still-behind-china-1563900.html[Accessed on 23 May, 2017].

[6]UNCTAD (2016)

[7]UNCTAD (2016)

[8]UNCTAD (2016)

[9]UNCTAD (2016)

[10]Xi Jinping (2017)

[11] Francoise Lemoine and Deniz Unal (2017), “China’s Foreign Trade: A “New Normal”” China & World Economy, Vol:25; N0:02 (Mar-Apr). p.10

[12] S. Rajasimman (2016), “BRICS: A Strategic Self Appraisal” Indian Defence Review, Vol:30, No:04, Oct-Dec 2015. Available at https://www.indiandefencereview.com/news/brics-a-strategic-self-appraisal/

[13]Ning Jizhe (Director of the National Bureau of Statistics) at a press briefing held by the State Council Information Office on 20 January, 2017 cited in Zhou Xiaoyan (2017), “Forging Ahead Against Headwinds” Beijing Review, Vol:60; No:07, February 16, 2017.

[14]Available at http://www.tradingeconomics.com/india/gdp-per-capita [Accessed on 22 May, 2017].

[15]Ananth Krishnan (2017), “Chinese Media Slams India’s ‘Meddling’ in Sri Lanka” India Today, 07 February. Available at http://indiatoday.intoday.in/story/chinese-media-slams-india-projects-sri-lanka-global-times/1/876627.html [Accessed on 23 May, 2017]Gabriel Domínguez (2015), “Sri Lanka’s New Leader to Visit China After Scaling Back Ties” Deutsche Welle, 25 March. Available at http://www.dw.com/en/sri-lankas-new-leader-to-visit-china-after-scaling-back-ties/a-18340803 [Accessed on 24 May, 2017]

[16]S. Rajasimman (2009), “China-ASEAN Relations: Emerging Asian Security Architecture” in Srikanth Kondapalli and Emi Mifune (Eds), China and its Neighbours (2010) Pentagon Press: New Delhi.

[17]Francoise Lemoine and Deniz Unal (2017), “China’s Foreign Trade: A “New Normal”” China & World Economy, Vol:25; N0:02 (Mar-Apr). p.1

[18] Ibid; p.1

[19]Ibid; p.9

[20]Cheng Li and Xiaojing Zhang (2017), “Renminbi Internationalisation in the New Normal: Progress, Determinants and Policy Discussions”China & World Economy, Vol:25; No:02 (Mar-Apr). p.40. Yongding Yu, Bin Zhang, and Ming Zhang (2017), “Renminbi Exchange Rate: Peg to A Wide Band Currency Basket” China & World Economy, Vol:25; No:01 (Jan-Feb).p.58.

[21]President Xi Jinping (2017)

[22]President of the People’s Republic of China, Xi Jinping’s Keynote Speech at the Opening Session of the 2017 World Economic Forum, “Jointly Shoulder Responsibility of Our Times, Promote Global Growth (共担时代責任共促全球发展)大v哦是,January17, 2017.

[23]Xi Jinping, President of the People’s Republic of China “Work Together to Build a Community of Shared Future for Mankind (共同构建人类命运共同体)” At the United Nations Office at Geneva, January 18, 2017.

[24]Former US Assistant Secretary C. Fred Bergsten, senior fellow and director emeritus, was the founding director of the Peterson Institute for International Economics (formerly the Institute for International Economics) from 1981 through 2012.

[25]On November 08, 2014, President Xi Jinping announced that China would invest $40 billion to set up the Silk Road Fund. It will serve as a complement to, rather than a substitute for, other global and regional multilateral development banks and will operate under the existing international economic and financial order. “Understanding China through Keywords” Beijing Review, 29 December, 2016. p.44

[26]Yang Jiechi (In-Charge of the Preparatory Work for OBOR) cited in “Welcome to the Belt and Road Forum”Beijing Review, Vol:60; No:07, February 16, 2017.

[27]China and India together account for 17.9 percent of global GDP and 13.2 percent of world trade as well as 58.9 percent of the total GDP of RCEP members and 47.4 percent of the group’s combined trade volume. RCEP represents 48% (3.5 billion) of world population and a combined GDP 22.7 trillion and trade volume of 9.58 trillion (29% of world trade volume).

[28]Wang Jinbo (2017), “New Opportunities under RCEP: The Early completion of the agreement will bring new opportunities for China-India economic and trade relations”Beijing Review, No:15, April 13, 2017.