The usage of the term, ‘war’ when battling terrorism or insurgency raises several issues. An important one is the use of the term ‘victory’ to delineate the desired objective in this conflict. There are vital differences between terrorism and insurgency and they cannot be clubbed together. Nevertheless, security forces have to root out this menace to modern societies. Talk and discussion should not be couched in terms of victory but as objectives to be achieved, as there are always dissenters against societal norms, who need to be accommodated within the mainstream. The conflict is not a zero-sum game. It needs a deeper understanding of the nature of the problem, especially in the Indian context.

‘War’ comes in many shapes and forms, has many different contexts, and is subject to diverse cultural influences. A paradigm shift in the nature of conflict is underway. People fight when they feel that (a) they can accomplish their objectives by force; (b) they feel that there is no alternative to their cause except the use of force; or (c) religion has swayed their ideological thinking into the notion that their cause is just. This has given a rise to terrorism and insurgency, which are the dominant threats we face today and are likely to face over the coming decades. It is a conflict where no one conception of the enemy is accurate, and it is a campaign which sees no decisive battle or an unconditional surrender by the vanquished. The threats are non-traditional, asymmetrical, and insurgent-terrorist in character.

“Mans mind, once stretched by a new idea, never regains its original dimensions.” ““ Oliver Wendell Holmes, 1809-1894

The change in the nature of warfare has led to the idea that the concept of victory in such a scenario is elusive. We face an uncommon terror campaign, a jihad aimed at the national jugular, coupled with ongoing insurgency campaigns. We may have difficulty identifying our moment of victory, but our defeat would not go unnoticed. There is a problem in definition. When we define terrorism as a violent criminal activity done to further some ideological goal, we will never be rid of it. Criminals – with and without ideological pretensions – will always be with us.

Defeating an enemy on the battlefield and forcing it to accept political terms is the traditional way of winning a war. One almost always defines victory as the juncture when one party surrenders to the other. The extent of the victory depends on what the vanquished is willing to give up in order to getting the victor to stop fighting. Secondary objectives also help set the targets for what it means to attain victory, and establishing what victory will mean at a particular time.

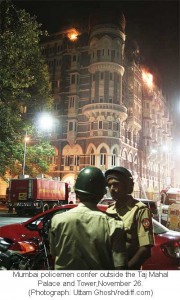

To try and define “victory” in the current struggle, we must understand why this is a war. The coordinated attacks at Mumbai on 26 November 2008 targeted our institutions of political, economic and financial power, and inflicted damage far beyond the loss of life or property. Beyond that, the scope of the malevolent purpose exceeded the objectives of the perpetrators of the violence. The real target of the attacks was the very infrastructure of Indian secular civilization. The nature of terrorism thus metastasizes into an ideology-driven assault on society.

Purpose always matters. As Oliver Wendell Holmes once said, ‘even a dog knows the difference between being stumbled over and being kicked’.1 Islamic terrorism is a coordinated and potentially effective series of attacks designed to destabilize, neutralize, demoralize, disrupt or destroy the support systems of the target civilization. What we are now experiencing is a major scale escalation of terrorism fueled by a single ideology with the goal of destabilizing India.This jihad is kept alive by passive or active state sponsorship, the infiltration of indigenous support systems within target states (including our own), and the establishment of stand-alone bases of operations, within the territory of nation-states hosting such groups and where they claim that they exert no effective authority. These terrorist groups have utilized, and still need facilities, finance, materiel, and logistical support of a kind and scale essentially unobtainable without the overt or covert cooperation of sponsor nation-states, which provide territory, funding and cover – and are part of the terrorist pipeline.

Purpose always matters. As Oliver Wendell Holmes once said, ‘even a dog knows the difference between being stumbled over and being kicked’.1 Islamic terrorism is a coordinated and potentially effective series of attacks designed to destabilize, neutralize, demoralize, disrupt or destroy the support systems of the target civilization. What we are now experiencing is a major scale escalation of terrorism fueled by a single ideology with the goal of destabilizing India.This jihad is kept alive by passive or active state sponsorship, the infiltration of indigenous support systems within target states (including our own), and the establishment of stand-alone bases of operations, within the territory of nation-states hosting such groups and where they claim that they exert no effective authority. These terrorist groups have utilized, and still need facilities, finance, materiel, and logistical support of a kind and scale essentially unobtainable without the overt or covert cooperation of sponsor nation-states, which provide territory, funding and cover – and are part of the terrorist pipeline.

The campaign against such a threat requires an unflinching willingness to inflict and to take casualties. In turn this calls for clarity of purpose, consistency and the capacity for occasional ruthlessness. A willingness to act boldly to punish terrorist cooperation, even on insufficient intelligence (and intelligence is always insufficient) is a very effective deterrent in itself.

Martin Van Creveld wrote as early as the late 1980s that inter-state war was a thing of the past, and that insurgencies and similar sorts of conflicts would constitute the future of warfare, and that militaries that ignored these facts were doomed to obsolescence.2 State failure and criminal instability rather than inter-state war poses the principal security risks of the future.3 A decisive victory is an indisputable military victory of a battle that determines or significantly influences the ultimate result of a conflict. It does not always coincide with the end of combat. There is, therefore, a need to define the concept of victory properly in terms of objectives to be achieved. “The guerrilla fights the war of the flea, and his military enemy suffers the dog’s disadvantages: too much to defend; too small, ubiquitous and agile an enemy to come to grips with.”4

The Existing Situation

South Asia is a key jihad theatre. Afghanistan was the principal Al Qaeda sanctuary until October 2001. A symbiosis developed between the Taliban government and numerous Islamist groups which shared facilities, and allied themselves, with Al Qaeda. Prominent among these was Lashkar-e-Toiba, which since the fall of the Taliban has become Al Qaeda’s principal South Asian ally. The Northwest Frontier Province (NWFP) and Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) on the Afghan-Pakistan border have become a haven for the Al Qaeda, who are cooperating with the Taliban remnants fighting as insurgents in the area. Pakistan itself has experienced Islamist subversion, agitation and terrorist activity, as has India. The ongoing insurgency in Jammu and Kashmir has been infiltrated by Islamist elements and Kashmir has become a major training and administrative area for Al Qaeda affiliates. The neighboring republics of former Soviet Central Asia (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan and Tajikistan) and the Xinjiang Uighur region of China have also seen Islamist subversion, terrorist activity and low-level insurgency.

A willingness to act boldly to punish terrorist cooperation, even on insufficient intelligence (and intelligence is always insufficient) is a very effective deterrent in itself.

It is now increasingly clear that a hard-line view of the Kashmir issue is ingrained increasingly in the religious as well as the political identity of Pakistan. Also, the Pakistani military considers the Kashmiri insurgent organizations to be a key asset, which they will not want to surrender.

The Muslim community in India is a huge group which, for the most part, is not talking about explicitly religious issues and is not a part of the international jihadi circuit. Most Indian Muslims primarily are concerned with local issues rather than Islamic world issues.

Several experts and analysts believe that conflict between two states can exist at lower levels indefinitely without much danger that such tensions will escalate into nuclear war. Many deterrence optimists suggest that third party intervention will always occur during a crisis and is consequently a major factor that will prevent escalation from getting out of hand. Therefore, while brinkmanship is ongoing in South Asia, every Indo-Pakistani war came as a surprise to one of the countries.

During the Kargil crisis Pakistan’s military moved to escalate the conflict with India without, apparently, informing the civilian leadership of the country. It is thus clear that Pakistan has political and constitutional problems, with the military over time having developed a comprehensive strategy for undermining civilian leadership and consolidating power once a coup takes place. The possibility of non-state actors to continue to act within Pakistan is a reality. Moreover, the danger of a loss of military control over militants in Pakistan remains a serious scenario.

The Emerging Pattern of Geopolitics

There is a global strategic environment, which presents many challenges in many different regions of the world that bear close attention in their own right. One is what is being called the Global War on Terrorism (GWOT), but it is really an assault against the West, Zionism and Hinduism by Islamist extremism, a virulent political ideology feeding on centuries of historical and cultural resentments. This ideological challenge is taking on a new geopolitical form.

In the traditional dimension of relations among the major powers, the re-emergence of Russia is one important feature of the current scene, but over the longer term the emergence of China represents probably a more dramatic change in the strategic landscape. It is the classical problem of a new great power appearing on the world stage, raising several complicated challenges of adjustment, for the world at large. The conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan, as well as the insurgency in Kashmir have added their own dynamics to an already skewed geopolitical situation.

the Global War on Terrorism (GWOT), but it is really an assault against the West, Zionism and Hinduism by Islamist extremism, a virulent political ideology feeding on centuries of historical and cultural resentments.

Carl von Clausewitz was one of the first to distinguish between limited and unlimited, or absolute, wars. Clausewitz’s absolute war was a theoretical abstraction, a concept of complete and total conflict that did not actually exist. He used it to examine the nature of war’s limitations. War could be limited in several ways: by the level of political demands of the combatants, the situation or condition of the belligerents, the strength of will on both or all sides, the degree of force employed, and much more.5 From this flowed his famous dictum that war is a continuation of politics: it is the political and policy environment that sets the limitations to conflict, for example, by dictating what resources belligerents will be able to employ.

Terrorism is an opportunistic infection in the human social condition. It is a problem greater than the sum of its parts. It emerges whenever any society’s immune system is sufficiently weakened. Complacency, cowardice and moral neglect are ever with us. Their darker companions – fevered minds with deadly weapons – will never be far away. Since we now live in an inter-connected world, terrorism cannot be seen in isolation against one particular nation or facet of civilization.

Insurgencies and extremist activity are the symptoms of political, economic, and psycho-social factors that undermine social stability and popular commitment to public order. Attached to the current war on terrorism is a very different sort of challenge: countering the rise of radical Islam. This radicalism is a product of popular reactions to incomplete and partially successful modernization, the inability of local governments to provide social goods, the perceived humiliation of Muslim peoples and interests globally, the relative socio-economic decline of parts of the Muslim world, amongst other factors. Such environments produce mind-sets filled with real and invented grievances, overwhelmed with the existential demands of modernity, and anxiety to revalidate a humiliated national or ethnic group by resuscitating ancient values.6 Such conflicts require the use of social, economic, political, informational, and psychological tools of statecraft.

The Dimensions of the Conflict

Mark Juergensmeyer, a leading authority on extremist thought, explained that a “war-against-terrorism strategy can be dangerous, in that it can play into a scenario that the religious terrorists themselves have fostered the image of a world at war between secular and religious forces. A belligerent secular enemy has often been just what religious activists have hoped for.”7 Since the state no longer has a monopoly on instruments of violence, recourse to violence is increasingly becoming a weapon of first resort. Terrorism can be contained and its effects minimized, but it cannot be eradicated, anymore than the world can eradicate crime. Resentments real or imagined, and exploding expectations, will remain.

A conflict can be termed asymmetric when either the political/strategic objectives of opponents are asymmetric or when the means employed are dissimilar. To analyze asymmetric warfare, it is vital to place it within a proper context. Militaries have always attempted to seek asymmetric advantages so as to inflict maximum damage to the enemy at minimum cost. Asymmetric strategies are especially favored by the weak because they tend to offset the conventional superiority of their opponents. Sun Tzu noted that, in general, one engages in battle with the orthodox and “gains victory through the unorthodox”.8 It also needs to be understood that there is a requirement to focus on specific threats with substantial evidence behind them; recognize that due process of law and the fight against terrorism go hand-in-hand; and that liberty and security are inseparable. As Benjamin Franklin wisely pointed out, “They, who would give up an essential liberty for temporary security, deserve neither liberty nor security.” The only way we can combat the loss of our freedom is to know exactly what we have to lose, what it means and how we can protect it.

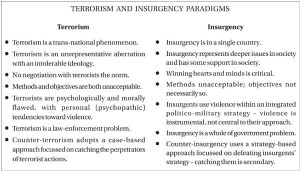

A conflict can be termed asymmetric when either the political/strategic objectives of opponents are asymmetric or when the means employed are dissimilar. To analyze asymmetric warfare, it is vital to place it within a proper context. Militaries have always attempted to seek asymmetric advantages so as to inflict maximum damage to the enemy at minimum cost. Asymmetric strategies are especially favored by the weak because they tend to offset the conventional superiority of their opponents. Sun Tzu noted that, in general, one engages in battle with the orthodox and “gains victory through the unorthodox”.8 It also needs to be understood that there is a requirement to focus on specific threats with substantial evidence behind them; recognize that due process of law and the fight against terrorism go hand-in-hand; and that liberty and security are inseparable. As Benjamin Franklin wisely pointed out, “They, who would give up an essential liberty for temporary security, deserve neither liberty nor security.” The only way we can combat the loss of our freedom is to know exactly what we have to lose, what it means and how we can protect it.Counter-insurgency and nation-building are different situations from the task of countering Islamic radicalism, but the utility of military force is often only marginally greater. The war cannot be won simply by killing the insurgents. We need to dissuade potential insurgents and those who are recruiting, training, and deploying them. Modern counter-insurgency doctrine rests on the truism that achieving lasting stability even, in the face of an armed insurgent enemy depends primarily on non-military actions and tools: building viable political institutions, resuscitating the national infrastructure, spurring the local economy, creating effective police forces, and much more. The security provided by large military forces may be an ongoing, sustaining pre-condition for such results, but it cannot guarantee them. Concomitantly, the actions of military forces run the risk of empowering the terrorists or insurgents by alienating the local population. The differences between terrorism and insurgency are outlined in the table below:

It is a mistaken notion that attainment of security is solely a function of military action alone. This is not arguing that military forces have no role in counter-insurgency, but stressing their extreme limitations. Where progress has been achieved, in counter-insurgency and counter-terrorism campaigns, it is attributable largely to political and economic factors rather than military ones. Asymmetric challenges demand asymmetric responses – political, economic, cultural, informational, and psychological tools, tactics, and techniques that work over time, not by military forces whose true purpose is to fight and win wars.

Benjamin Franklin wisely pointed out, “They, who would give up an essential liberty for temporary security, deserve neither liberty nor security.”

Democratic institutions are a cause of vulnerability to asymmetric coercion. The transparency of decision-making processes and openness of democratic society, in general, makes it easy for potential enemies to discern asymmetric vulnerabilities clearly. Technology has also ironically increased vulnerability to asymmetric threats. The insurgents and terrorists can tap into deep-rooted national, ideological, ethnic, tribal, or religious grievances and exploit them for their devious purpose.

Unity of effort is an acknowledged principle of war. Operations in this war, at any level, will achieve strategic clarity and maximum effectiveness by integrating both horizontal and vertical planning and implementation processes from the outset. These are two fundamental organizational mechanisms necessary to help eliminate ambiguity, ad-hocism and mission-creep.

How could the United States have won all the battles in Vietnam, but lost the war? The answer is straight-forward. American leadership failed to apply the fundamental principles of military theory and grand strategy in that conflict. The experience brings out five highly inter-related strategic-level lessons. They are:

- the need to carefully examine and define the nature of a given conflict;

- fully understand the strategic environment within which the conflict is taking place;

- determine the primary centres of gravity within that strategic environment that must be attacked and defended;

- appreciate the “centrality of rectitude” in pursuing a given strategy or in supporting a given effort; and

- examine these lessons as a strategic whole.

The central unifying theme of these lessons is decisive. The instruments of national power must be organized, trained, and equipped within prescribed considerations. These must be preceded by clear, holistic, and logical policy direction – and the structure, roles, missions and strategy that will ensure the achievement of the political ends established in that policy. This is a fundamental “rule” that is as valid for current and future conflict as it has been in the past.9

Also read: Operation Nandigram: The Inside Story

Sun Tzu stated that, “War is of vital importance to the State; the province of life or death; the road to survival or ruin. It is mandatory that it be thoroughly studied.”10 And Clausewitz reminds us that “The first, the supreme, the most far reaching act of judgment that the statesman and commander have to make is to establish . . . the kind of war on which they are embarking; neither mistaking it for, nor trying to turn it into, something that is alien to its nature.”11 Determining the nature of the conflict is thus “the first of all strategic questions and the most comprehensive.”12

The primary problem is to re-evaluate constantly the principal threat and the proper order of priority for the others. The secondary problem is to develop the capability to apply long-term political, moral, psychological, and economic resources – as well as military – against the various centres of gravity that this type of war generates. Shrinking from these inevitable requirements for success in conflict only prolongs the struggle. Sun Tzu reminds us that, “. . . there has never been a protracted war from which a country has benefited.”13

There is no international terrorism without the support of sovereign sponsor-states. It cannot be sustained for long without regimes that aid and abet it.

Every war will be unique. It will reflect the history, geography, and culture of the society in which it occurs. Yet, there will be analytical commonalities – and strategic-level principles – that continue to be relevant. “The past of guerrilla warfare and insurgency represents both the shadow of things that have been and of those that will be.”14 Our challenges are interconnected. We have the skill and resources to do what is necessary. What we also need is the will.

Towards Victory

There is no international terrorism without the support of sovereign sponsor-states. It cannot be sustained for long without regimes that aid and abet it, and provide the terrorists with intelligence, money, and operational assistance, dispatching them to serve as deadly proxies to wage a hidden war against more powerful enemies. Victory over terrorism is not, at its most fundamental level, a matter of law enforcement or intelligence. However important these functions may be, they can only reduce the dangers, not eliminate them. The immediate objective is to end all state support for and complicity with terror.

The war against terror is a zero-sum game in which there can be only one winner. In this war, the terrorist or insurgent wins if he only does not lose, while the State loses if it can not win. There is no place for an honorable draw. Victory in any kind of war is not simply the sum of the battles won over the course of a conflict. Rather, it is the product of connecting and weighing the various elements of national power within the context of strategic appraisals, strategic vision, and strategic objectives. The more a terrorist attack recedes from our memory, the more difficulties we will have in developing and implementing a really robust domestic anti-terrorist programme.

The war against terror is a zero-sum game in which there can be only one winner. In this war, the terrorist or insurgent wins if he only does not lose, while the State loses if it can not win. There is no place for an honorable draw. Victory in any kind of war is not simply the sum of the battles won over the course of a conflict. Rather, it is the product of connecting and weighing the various elements of national power within the context of strategic appraisals, strategic vision, and strategic objectives. The more a terrorist attack recedes from our memory, the more difficulties we will have in developing and implementing a really robust domestic anti-terrorist programme.

When can we declare victory, and by what parameter can we detect its arrival? What would constitute a victory for India in the confrontation with Pakistan over terrorism? Terrorist gestation within a country or region has lead times comparable to cancers. The measure of success suffers from the same uncertainty inflicted on every recovering cancer patient. Cancer “cure” rates are measured by the number of years without a recurrence. If we are winning we can expect that terrorism against us will not involve major national assets and will reduce in scale, falling into the background noise of ordinary crime.

Above all, is the need to fight the media war. Public relations campaigns must be strong and strategic. There is an imperative need to understand how media works, how best to utilize its blind spots and prejudices.

The ultimate outcome of any counter-insurgency or counter-terrorism effort is not primarily determined by the skillful management of violence in the many battles that take place. Rather, control of the situation is determined by the level of moral legitimacy; organization for unity of effort; type and consistency of support, intelligence and information; the ability to reduce internal and external aid to the insurgents; and the discipline and capabilities of the security organization involved in the “war.” To the extent that these factors are strongly present in any given strategy, they favor success. To the extent that any one component of the model is absent, or only present in a weak form, the probability of success is minimal.

There is a need to develop robust covert systems of surveillance, infiltration, detection, disruption and destruction of terrorist cells, infrastructure, and support within the country. We need an intelligence capability several steps beyond the usual required for anti-crime operations. This capability involves active utilization of intelligence operations as a dominant element of both strategy and tactics.

Above all, is the need to fight the media war. Public relations campaigns must be strong and strategic. There is an imperative need to understand how media works, how best to utilize its blind spots and prejudices. The requirement is for a clear vision, networking capacity and the resources to use world media to full effect.

There is also a requirement for a national executive-level management structure that can and will ensure continuous cooperative planning and execution of policy among and between the relevant civilian and military agencies (i.e., vertical and horizontal coordination). Such an organizational structure must also ensure that all civil-military action at the operational and tactical levels directly contributes to the achievement of the national strategic political vision.

Since the state no longer has a monopoly on instruments of violence, recourse to violence is increasingly becoming a weapon of first resort. Terrorism can be contained and its effects minimized, but it cannot be eradicated, anymore than the world can eradicate crime.

The famous anthropologist, Margaret Mead once said, “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world. Indeed, it’s the only thing that ever has.” And the German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer said, “All truth passes through three stages. First, it is ridiculed. Second, it is violently opposed. Third, it is accepted as self-evident.”

Conclusion

Operations conducted against terrorists and insurgents are designed to increase the security of citizens. Bringing down terrorism, most experts agree, is a long-term project. Its success largely depends on the Muslim world dealing with radicalism in its midst. To achieve “peace without victory” requires unusual magnanimity in a society, as the opposite of peace without victory, grammatically speaking at least, is victory without peace. What then is the way forward? One thing is certain; this war’s end is very likely to be far different from its beginning. It is a hard road ahead, and while those fighting the war may need more weaponry, they definitely need more patience.

Even though every conflict situation differs in time, place, and circumstance, none is ever truly unique. Some experts predict that Islamic extremists will lose, the way the USSR did with its ideology and tactics discredited. This will occur, they aver, as a result of the Islamic world rejecting the militants’ use of violence against other Muslims, the economic failure of extreme Islamic regimes and wariness in some Muslim nations that terrorist groups like Al Qaeda could impose their rule.

The struggle against radical terrorism and insurgency is difficult and long, but it is not one that we can afford to lose. Everyone who is concerned about the safety and security of our nation must stand up and work to educate themselves and others about the nature of extremist terrorism, and maintain public support for victory. The only way the terrorists can win is if we give up as a society and cease to defend our democratic values against the terrorists’ demands.

If you want to overcome your enemy you must match your effort against his power of resistance, which can be expressed as the product of two inseparable factors, viz. the total means at his disposal and the strength of his will. The extent of the means at his disposal is a matter ‘though not exclusively’ of figures, and should be measurable. But the strength of his will is much less easy to determine and can only be gauged approximately by the strength of the motive animating it.15 To quote Oliver Wendell Holmes again, “I find the great thing in this world is not so much where we stand, as in what direction we are moving: To reach the port of heaven, we must sail sometimes with the wind and sometimes against it, but we must sail, and not drift, nor lie at anchor”.16

Notes

- Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.; “The Common Law”; See http://www.jurid.net/biblio/CommonLaw/cmnlw10.htm (Accessed on 12 January 2009).

- See Martin Van Creveld, Through the Glass Darkly: Some Reflections on the Future of Warfare, Naval War College Review 53, no. 4 (Autumn 2000): 25-44; Martin Van Creveld, The Transformation of War (New York: Free Press, 1991).

- Robert Kaplan, “The Coming Anarchy,” Atlantic Monthly, February 1994, http://www.theatlantic. com/doc/199402/anarchy.

- Taber, Robert, The War of the Flea, (London, Granada Publishing Ltd., 1965) p.29.

- Carl von Clausewitz, On War, ed. and trans. Michael Howard and Peter Paret (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1976), pp. 579-594.

- See Marc Sageman, Understanding Terror Networks (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004), pp. 17, 95-98; Michael J. Mazarr, Unmodern Men in the Modern World: Radical Islam, Terrorism, and the War on Modernity (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007).

- Mark Juergensmeyer, Terror in the Mind of God: The Global Rise of Religious Violence, 3rd ed. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003), pp. 190-193, 235.

- Sun Tzu, The Art of War, Samuel B. Griffith, trans., London: Oxford University Press, 1971, p. 63.

- Max G. Manwaring; Internal Wars: Rethinking Problem And Response; (Strategic Studies Institute, U.S. Army War College Monograph); September 2001; p.8

- Sun Tzu (1993): 165.

- Carl von Clausewitz, On War, Michael Howard and Peter Paret, ed. and trans., Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1976, p. 88.

- Ibid., pp. 88-89.

- Sun Tzu, p. 73.

- Ian Beckett, “Forward to the Past: Insurgency in Our Midst,” Harvard International Review, Summer 2001, p. 63.

- Clausewitz, On War, pp. 75, 77.

- Oliver Wendell Holme, “The Autocrat of the Breakfast Table” (1858); originally published in The Atlantic Monthly.