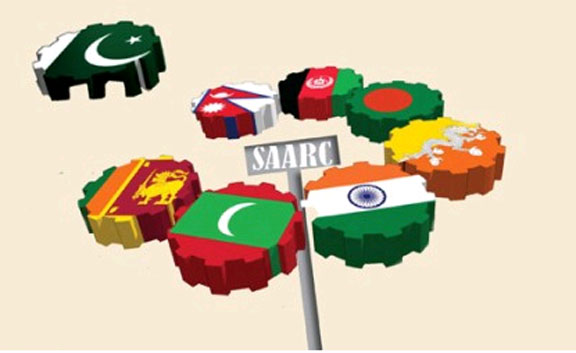

In the following pages, a regular contributor to this magazine, who happens to be veteran journalist of the country, has described why the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) has no future as long as Pakistan remains its member. In fact, in the context of the recent postponement of the SAARC summit (following the boycott-decisions by India, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal, the Maldives and Afghanistan) that would have been the 19th in the series and was scheduled to be held in Pakistani capital Islamabad in November, the demand for a SAARC without Pakistan is gaining momentum.

In the following pages, a regular contributor to this magazine, who happens to be veteran journalist of the country, has described why the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) has no future as long as Pakistan remains its member. In fact, in the context of the recent postponement of the SAARC summit (following the boycott-decisions by India, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal, the Maldives and Afghanistan) that would have been the 19th in the series and was scheduled to be held in Pakistani capital Islamabad in November, the demand for a SAARC without Pakistan is gaining momentum.

It is being increasingly realised that since Pakistan is not interested in implementing the existing SAARC decisions on regional connectivity, trade and terrorism, and it continues to interfere in the internal matters of other member countries in sharp violation of the SAARC Charter, it will be better to proceed with a “small SAARC” option.

Of course, some may argue that according to the current SAARC charter, there is no mechanism for removing a member-state. As the Charter talks of SAARC functioning on the principle of unanimity, thus giving each of the eight member-countries a veto power, Pakistan cannot be expected to agree to its expulsion from the group. One way out is that Pakistan, given its increasing isolation in the region, should voluntarily leave the group. But that looks highly unlikely. Therefore, an alternative-route has to be found so that SAARC becomes vibrant by making Pakistan redundant in the group. By so doing, Pakistan will not be able to play a victim card and accuse India of pursuing “hegemonic designs” in the region.

It may be noted that the SAARC, which represents a poverty-stricken region that is home to more than 1.5 billion humans, a fourth of the world population, was launched in 1985, thanks to the initiatives of the late Bangladesh President Ziaur Rahman. It began with seven countries of the Indian subcontinent – Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka. Subsequently Afghanistan joined the group. But, what has the SAARC achieved in the last 31 years? Whatever the officials may say, the fact remains that the record of the organisation has nothing concrete to boast of. In the inaugural conference of the SAARC in 1985, poverty eradication and improving the living standards through mutual cooperation were the main themes. If the same themes are being still talked about after 31 years, it only reflects the poor health of the organisation.

SAARC remains one of the least integrated regions of the world. The intra-trade is minimal, with less than five per cent of the region’s global trade taking place among SAARC nations. The SAARC Agreement on “Suppression of Terrorism” has remained on paper. And so has been the case with the SAARC’s commitment to the goals of the “SAARC Charter for Democracy”, with so many military coups and unstable as well as corrupt governments. Various SAARC summits have addressed issues of regional concern such as poverty, food security, trafficking in women and children and drugs, etc. But on each of these issues, South Asia as a region continues to have a notorious distinction.

The fact that SAARC as a regional grouping has not lived up to expectations could be attributed mainly to the very nature of South Asia as a region. In South Asia, India overwhelmingly dominates over others in size, population and economy. Except with India, no SAARC nation shared border with another SAARC nation before Afghanistan joined the group (it shares the border with Pakistan). Politically, apart from India and Sri Lanka, no other SAARC country can boast of having strong democratic roots.

Ethnically, India has got communities which have strong civilisational and cultural affinities with a section of community in each of the other SAARC countries – Tamils in Sri Lanka, Bengalis in Bangladesh, Biharis and those from Uttar Pradesh with Madhesis in Nepal, North Indian Muslims with the so-called Mohajirs in Pakistan etc. As a result, the India-link becomes a political factor in almost all the SAARC countries. And above all, there is the legacy of partition of India in 1947, giving birth to a new country called Pakistan and subsequently Bangladesh. This legacy continues to bedevil the relations between India and Pakistan, SAARC’s two largest countries.

There is no mistaking the fact that Pakistan had joined the SAARC in 1985 with a clear view to utilise the organisation as an anti-India platform by mobilising the smaller nations of the region. In fact, when it was requested by the Bangladesh President Rahman to join the body, there were serious debates within the country whether by so doing, Pakistan’s main goal of consolidating itself as a “West Asian” and “Islamic” country, with strong links with the Arab world, will be compromised. But if Pakistan finally decided to join the forum, the main reason why it did so was its strategy of using the SAARC forum “to deflect the weight of India” vis-à-vis its smaller South Asian partners.” It felt that by being inside the forum it could prevent India from assuming “a hegemonistic role” in the region.

Pakistan was (rather is) simply not interested in the primary SAARC objectives of collective and mutually beneficial efforts “to promote the welfare of the peoples of South Asia and to improve their quality of life” and “to accelerate economic growth, social progress and cultural development in the region and to provide all individuals the opportunity to live in dignity and to realise their full potentials.” Viewed thus, the boycott of the Islamabad summit by as many as six countries, including Bangladesh, is a big setback to Pakistan’s traditional SAARC-objective.

As far as India is concerned, from a short-term point of view it is a huge vindication of the present policy of the Modi government to isolate Pakistan internationally for its attack on Uri and diabolic role in the ongoing unrests in the Kashmir valley. But from a long-term point of view, it is also a setback to promote Modi’s ideas of regional amity and integration in South Asia.

It may be noted that Modi’s first day on office as prime Minister on May 26, 2014 was marked by exclusive bilateral meetings with the leaders of the SAARC countries — Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Nepal, Maldives, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka – who were specially invited to attend his swearing-in. His first foreign visit as the Prime Minister was to Bhutan and then to Nepal. In fact, there are merits in the argument that Modi’s “Neigbours First Policy” was to make a developed and prosperous South Asia a viable counterweight to China, which has succeed considerably in making significant inroads in the region.

In fact, it was Modi who had proposed in the last SAARC summit in 2014 at Kathmandu three ideas dealing with cooperation on energy (cross-border trade in electricity and create a seamless power grid across South Asia), easier access for motor vehicles (to allow vehicles of SAARC countries to travel in neighbouring countries unhindered to transport cargo and passengers), and promotion of railways in the region. But as usual, Pakistan alone did not allow the signing of agreements on these proposals during the summit. The only thing Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif agreed on was to sign “the framework agreement on regional electricity connectivity”, the details of which have yet to be worked out.

Be that as it may, the diehard supporters of the SAARC miss no opportunity to cite the success stories of Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) and the European Union (EU). But they miss the point that neither the ASEAN nor the EU has such disparities among its members as these are within the SAARC. Neither the EU nor the ASEAN has a giant like India within it which is superior in every respect to its neighbours.

Then there is the common security perception. The fear of China brought the ASEAN countries together in 1970s. And the fear of the then Soviet Union made the then European Coal and Steel Community and the European Economic Community, the predecessors of the EU, possible. But here in South Asia, while India has always chalked out a course of autonomy in its interactions with the rest of the world, other SAARC members have been guided at different times differently by the United States and China.

This is not to suggest that the SAARC is not a useful organisation. Despite all its limitations, in the last few years, particularly since the 14th Summit in New Delhi in April 2007, SAARC has begun to lay the institutional framework for regional cooperation. Regional institutions, in the form of the South Asian Regional Standards Organization (SARSO) in Dhaka, the SAARC Arbitration Council in Islamabad, the SAARC Development Fund (SDF) in Thimphu, the South Asian University (SAU) in New Delhi, among others, are the building blocks of regional development.

However, as I have argued above, the future success of the SAARC lies in making Pakistan irrelevant. India should (and it already is) create alternate group conversations such as BBIN (Bangladesh-Bhutan-India-Nepal), and lead more such conversations and consortiums and make such alternate gatherings aspirational for others to sign up. In other words, the only way ahead is to promote sub-regionalism within the SAARC to carry out the developmental projects and other integrating ideas. India and Sri Lanka on the one hand, and Bangladesh, Bhutan, India and Nepal on the other could join hands to work together.

As it is, there is already the Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation (BIMSTEC) that connects South Asian countries (except Pakistan and Afghanistan, which are not members) with Myanmar and Thailand. Connectivity and development through the sub regional route is very much permissible under the SAARC Charter (“Principles” 2 and 3). The idea is to go ahead without Pakistan.

Courtesy: http://udayindia.in/2016/10/21/a-saarc-sans-pakistan/