Introduction

Why is it that only Indians record their military history Service-wise? All other Nations record their histories from a tri-service military viewpoint, theatre-wise, chronologically. If we are to promote synergy within our three Services, for optimum utilisation of integrated military power in National interest, we must view all campaigns from an overall military viewpoint, alone.

Soon after the historic War of 1971, even before the euphoria of victory subsided, some writers rushed to publish war accounts. There was a tendency to underplay the weaknesses noticed, lest they tarnish the sheen of victory. Later accounts, though more accurate and objective, did not bring out lessons for the future, for various reasons.

As we celebrate the 50th anniversary of this decisive war, we need to look at the war from a tri-service viewpoint and highlight lessons that must be learned by the armed forces.

AIMS OF THE WAR AND TASKS OF THE SERVICES

The political aim of the War, was to create conditions for the formation of a government of the duly elected representatives by the people of East Pakistan in the December 1970 elections. This was to facilitate 10 million East Pakistani refugees in India, to return to their homes.

India had no territorial ambitions, though the Army took advantage of the war thrust upon India, to secure some tactically important territory in J&K, where the Ceasefire Line was finally converted to a Line of Control. We lost Chhamb and some areas in Punjab, for reasons which need objective analysis.

To achieve the aim of the war, the Army’s Eastern Command, the Eastern Naval Command and the Eastern Air Command were tasked to establish Bangladesh. Strategic defence was adopted on the Western Front, which included offensive operations. Western Naval Command and Southern Naval Area were tasked to protect the territorial waters, off-shore and on-shore assets, protect own shipping and deny sea lanes to Pakistani shipping.

WAR IN THE EAST

Background

Despite the unprecedented win of the Awami League in Pakistan’s General Elections in 1970, the West Pakistanis refused to hand over the reins of power, to the elected Party, which led to widespread agitations in Bengal. President Yahya Khan despatched troops to subjugate the Bengali population by brute force. The reign of terror unleashed on the people, further alienated the population and forced them to rebel. On 25 March 1971, Sheikh Mujibur Rehman declared Bangladesh an independent Nation. He called upon his people to fight the barbaric Pakistan Army in Bengal.

The consequent genocide by the Pakistani Army forced millions of people to flee to India. Appeals by the Indian leaders and diplomats to world powers to intervene, fell on deaf ears.

The Indian Government realised that mere appeals would not enable the refugees to return to their homes. It therefore provided essential support to the freedom fighters who organised themselves to fight the Pakistan Army. Thus was born the Mukti Bahini. Servicemen who left the Pakistani armed forces organised themselves to fight for the freedom of their people. However, by October 1971, it was apparent that the freedom fighters could not defeat the Pakistan armed forces on their own. Some assistance was required from the Indian armed forces, to end the carnage.

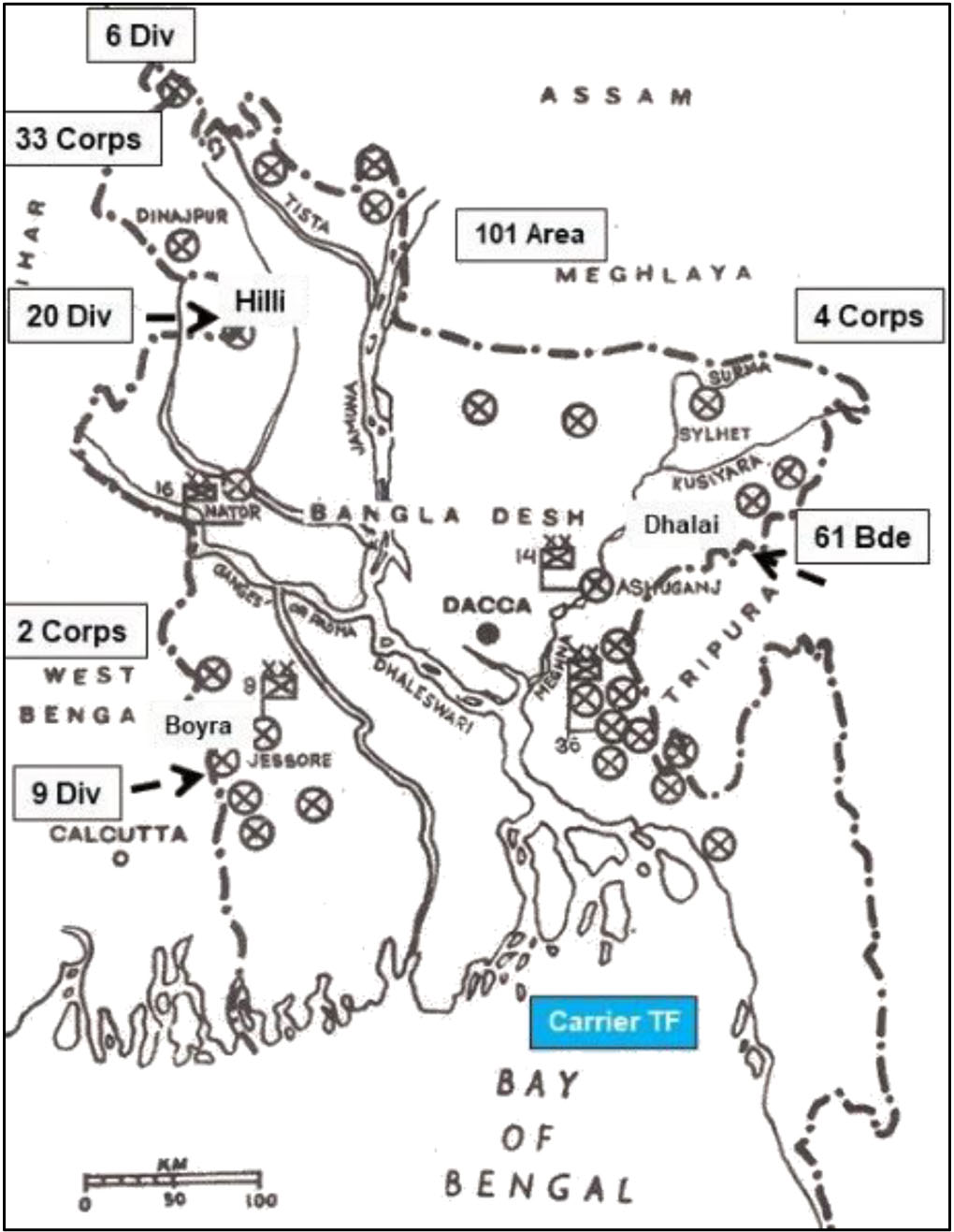

In October-November 1971, the Indian Army attacked a few objectives in East Pakistan. These were Dhalai, Hilli and Boyra. All three turned out to be strongly defended and were captured at a high cost, which throws up an important lesson, listed at the end of this paper.

Map of East Pakistan showing deployment of Indian formations

Land-Air Battles

When Pakistan attacked India on 03 December 1971, 11 squadrons of IAF combat aircraft in the East, established air supremacy over the next two days1.

Three Indian Corps thrust deep, bypassing strongly defended fortresses. By 10 December, the initial objectives had been captured, assisted by the IAF and the Mukti Bahini.

The Eastern Fleet of the Indian Navy blockaded East Pakistan completely, which sealed the fate of Pakistan’s armed forces in the East. Even though the final objectives were still distant, the Army and the IAF commenced moving out forces to the Western theatre.

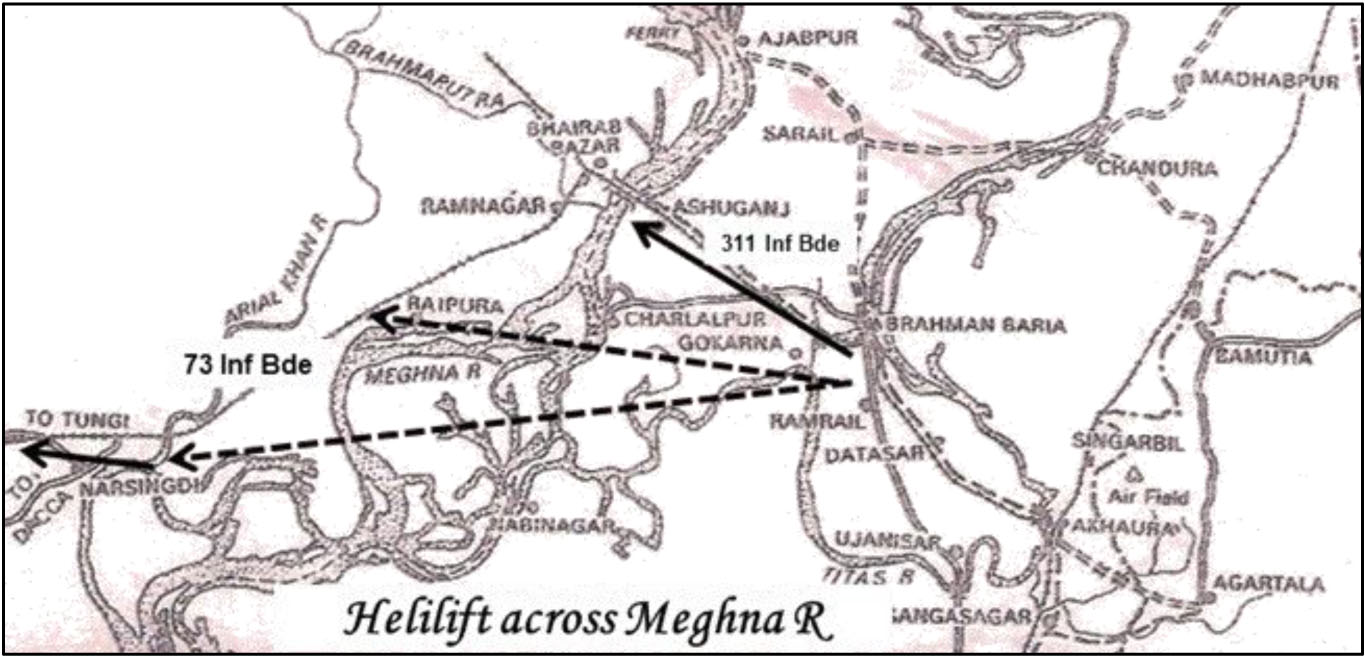

Crossing of the Meghna by 57 Mtn Div

The Naval Blockade

The Indian Eastern Fleet had 14 ships including the aircraft carrier INS Vikrant, one cruiser and one submarine. Pakistan Navy (PN) in the East had 19 vessels including a long-range submarine PNS Ghazi, one destroyer and a gun boat squadron of four fast gunboats. Of these, one gunboat, PNS Rajshahi, managed to escape while all others were destroyed by the IN and the IAF2.

The Indian Carrier task force was at sea when Pakistan deployed PNS Ghazi off Vizag. INS Rajput sailed out to destroy the submarine, and dropped depth charges. The submarine sank on 03 December, probably due to a mine accident. When the war commenced, the carrier task force closed in and attacked Cox’s Bazar. They enforced a blockade, attacking several ports in conjunction with the IAF, to destroy several Pakistani vessels. An assault landing was attempted, but finally a battalion was landed by boats, highlighting the need for deliberate planning and training for amphibious operations3. The IN suffered no losses in the East.

Cyber War

Signal intercept units of the Indian Army provided valuable information in real time, which was gainfully used both for operations and for info war.

Victory

The Army formations, assisted by the IAF, East Bengal brigades and Mukti Bahini, continued their advance and soon reached Dhaka and all other population centres in Bangladesh. The Pakistani Generals saw the writing on the wall; hence commenced asking for ceasefire, 14 December onwards. The Eastern Army Commander accepted unconditional surrender of the Pakistanis, on behalf of all Indian and Bangladeshi forces, at 4.31 PM on 16 December, at the Dhaka Race Course. It was India’s greatest hour.

An Observation on Vertical Envelopment

Conditions in East Pakistan were ideal for use of heliborne troops. The terrain was riverine, air superiority was complete, and Eastern Command had one Parachute brigade, trained for vertical envelopment. The IAF had 80 MI 4 utility helicopters4 in addition to a few MI 8s. It needs to be asked as to what prevented use of these resources to speed up operations. Why were only a dozen helicopters used to lift infantry battalions? Why were all the resources in our inventory not used?

There is little point in the Services acquiring vast resources, if these are not used in war.

As the world watched India win a decisive victory, the forces on the Western Front fought hard to execute their tasks, which were far more challenging.

WAR IN THE WEST

Force Levels

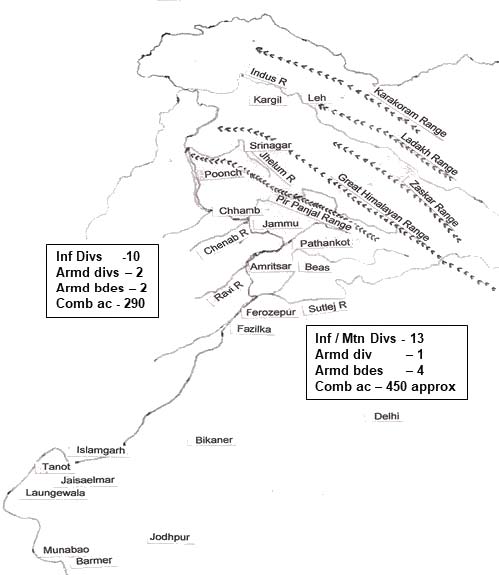

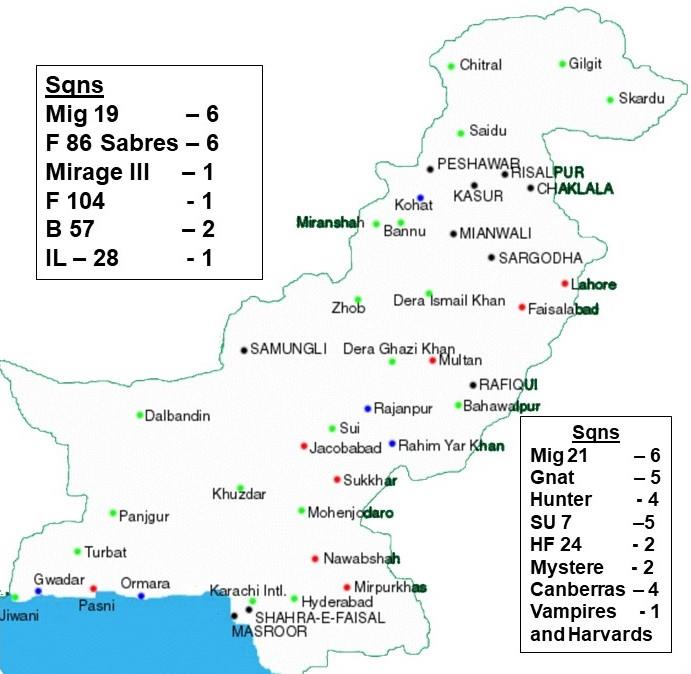

While the land forces on the Western Front were evenly matched, the IAF enjoyed considerable superiority over the adversary (details given on map). They had 28 squadrons with about 450 combat aircraft in the West. Against this, the PAF had 17 squadrons plus about 35 additional fighters provided by some Islamic states, with about 290 combat aircraft (though different books give different figures), (See map). The Navies on either side were evenly matched5.

Map showing forces on the Western Front

Preparations for War

On 01 December 1971, the PM surprised the Army Chief by directing that the Indian forces would not initiate war, nor were they to take actions that could provoke hostilities in the West. This does raise a question as to why was such a decision not taken earlier, when it was clear that war was inevitable? What happened in end of November for us to change our broad strategy? Nevertheless it happened, and the lesson is that the armed forces must have contingency plans for such eventualities, and the flexibility to accept changes.

Map showing Pak airbases and combat aircraft in the West

As a result of the PM’s direction a few formations, whose role was suddenly changed, were preparing defences when the war broke out two days later6.

Pakistan Initiates War

PAF attacked many Indian airfields using about 30 percent of their strength on the 3rd evening. Being alert, the IAF suffered negligible damage. Pakistani air attacks were followed by one major offensive and three brigade size offensives.

Initial battles

The Air battle was most intense on 04 December when both sides suffered heavy losses; thereafter the intensity reduced gradually, though both air forces remained aggressive till the end of the war.

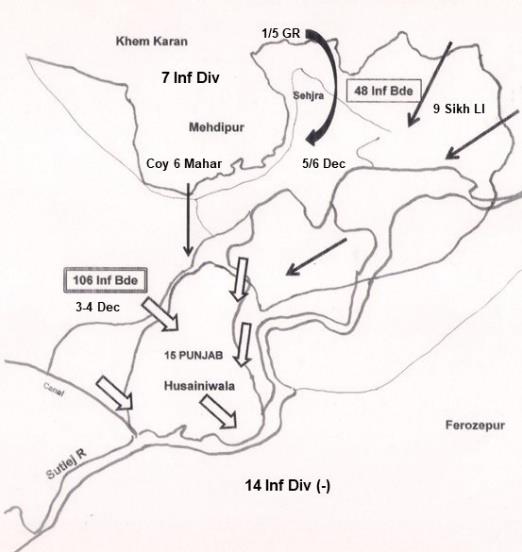

Husainiwala and Sehjra

Of their 28 squadrons in the West, the IAF earmarked 9 squadrons of MiGs and Gnats to protect the airbases. The other squadrons, which included six of MiGs, five of Gnats and four of Hunters, were earmarked for ground attack, which included attacks on Pakistani airbases. Two fighter squadrons were moved from the East to the West by 08 December7.

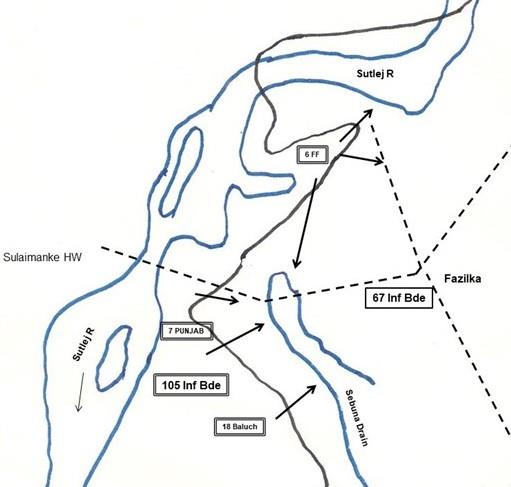

Pakistan launched two brigade size offensives in Punjab, to capture Husainiwala and some area in the Fazilka sector. A third offensive was launched towards Laungewala. Since the last mentioned was launched without any air cover or air support, the Pakistani tanks, vehicles and Infantry presented easy targets for IAF Hunters at Jaisalmer.

Fazilka

Operations in J&K

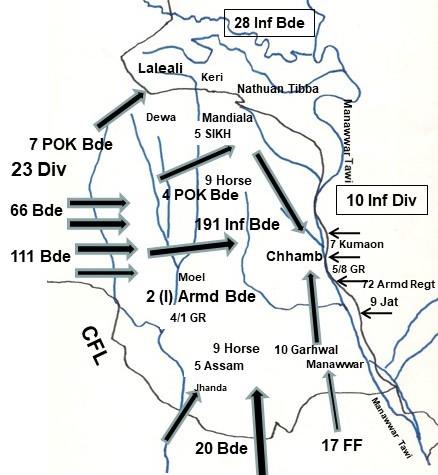

On the first night of the war (03/04 December), Pakistan launched a major offensive to capture Akhnur. This was well planned and provided maximum air support. The offensive was led by a dynamic General of the Pakistan Army. Indian 10 Infantry Division, whose task had been changed from offensive to a defensive only two days earlier, was surprised; but fought well, halting the enemy at Munawwar Tawi by 10 December8.

Chhamb

Even as the battle raged in Chhamb, Indian formations in the north captured important heights in the Shyok Valley, Kargil, Tangdhar and Lipa sectors. Pakistan launched two infantry battalions to capture Poonch which were defeated by two brigades, namely 93 Infantry Brigade and an additional infantry brigade (33) from the plains. The battle lasted two days. After 05 December, the additional brigade remained idle for the rest of the war. It was neither returned to its parent formation nor employed in Chhamb to help restore the adverse situation.

Chhamb

With one additional brigade, 10 Division limited the Pakistani ingress to the Munawwar Tawi and asked for additional forces to recapture lost territory, but instead of receiving additional forces, 10 Division was ordered to send some resources to neighbouring sectors9. At that stage of the war, there were eight infantry brigades and five armoured regiments available in Akhnur – Jammu sector, plus 33 Inf Bde was located at Poonch. From the Jammu – Poonch sectors at least two brigades and one armoured regiment could have been moved to Akhnur to recapture lost areas.

Air Support for the Battle in Chhamb

Close air support received by 10 Infantry Division was highly inadequate, hence needs objective analysis to learn lessons for the future. Some pertinent statements made by OC 4 TAC, throw light on the matter. In his book, My Years with the IAF, ACM PC Lal quotes the OC 4 TAC saying:-

“The front was barely 10 mile wide allowing not more than two aircraft to fly in the area at any one time.” Then on the same page the ACM states, “More air support could have been provided …. with the resources allotted to 4 TAC if only the Army had asked for it in that sector. What the Corps should have done was to liaise with the TAC Commander and divert more effort where it was required”.

On the subject, ACM PC Lal goes on to say:-

“The Corps Commander, Lt Gen Sartaj Singh, visited the TAC once during the operations. ….. a major of the General Staff was meant to liaise with the TAC, but he was unable to filter out demands and assign priorities to them. …. Since demands were coming in with no guidance from the Division or Corps HQ to allot priorities, Chhabra (OC TAC) set up a ‘search and strike’ routine over the area. More air support could have been provided ….. if only the Army had asked for it in that sector.”10

But the Army had asked for the air support! What else were they expected to do? Information of the inadequacy of air support was reported to the Prime Minister on 06 December, as stated in his book, ACM PC Lal, as follows:-

“The complaint went to the COAS, whose Director of Operations spoke to the Deputy Chief of Air Staff who said that adequate air effort had already been assigned to 4 TAC. The COAS then spoke to the Prime Minister who called me. I asked the AOC-in-C Western Air Command,

……., to give more air support to Chhamb and he diverted more aircraft to that sector. It was in this way that eventually OC 4 TAC learnt that he was falling short of army expectations.”10

It seems the CAS expected the Corps Commander, who was visiting battle areas from the Shyok Valley to the Jammu Sector, to visit 4 TAC often to get air support for the Corps! The incident quoted above happened on 06 December, but again on 10 December, GOC 10 Infantry Division had to speak to the Corps Commander to ask for maximum air support.

Whosoever was to blame, the lesson emerges that this was hardly the way to fight a war. There is no point in the Nation acquiring vast, expensive resources, if these are not utilised optimally in war. If lack of synergy was one major reason for the loss of Chhamb, corrective action is essential.

The ACM also observed that TAC commanders need to be selected with greater care. He writes:-

“It may be better, if possible, to appoint a fighter pilot as a TAC commander rather than a navigator10 …..”

While, this was the sorry state of affairs on the Indian side, opposite them the PAF had placed an Air Commodore to coordinate the air support to the Pakistani 23 Infantry Division.11

One hopes our mutual understanding and synergy will be better in future wars.

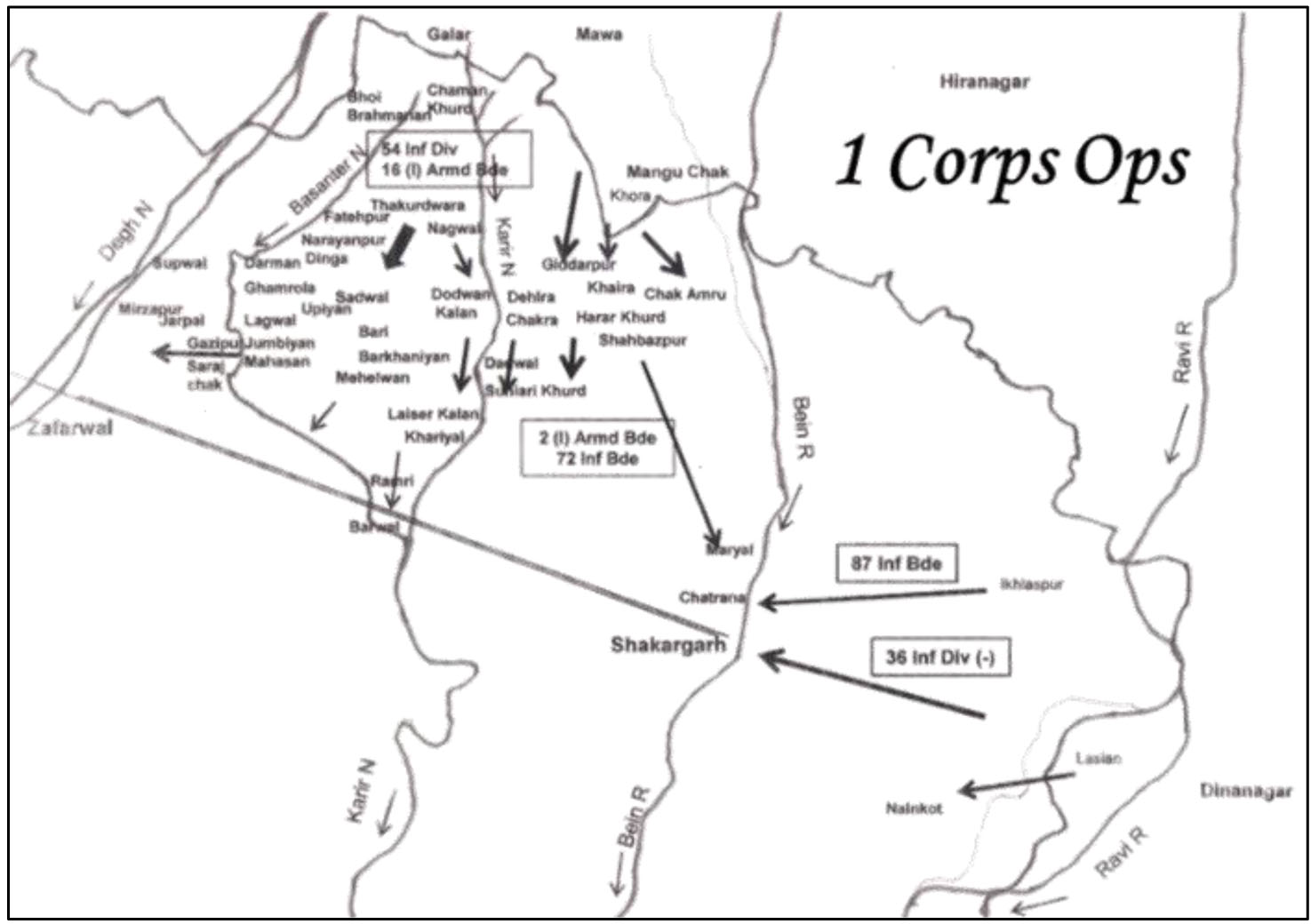

Shakargarh

In the Plains sector of J&K, the vulnerability of the Pathankot-Jammu Road is well known. 1 Corps had been deployed and tasked to defend this sector. The formation took the battle into enemy territory by launching an offensive across the IB, on 05 December. Though the offensive was slow and cautious which led to avoidable casualties, it retained the initiative and kept the war on Pakistani territory.

1 Corps Offensive

It is pertinent to mention that the Infantry and armour functioned under different formations, under the Corps HQ. They had neither trained nor functioned together before the war. There was little synergy between the two.

Punjab

In Punjab, 11 Corps captured the DBN Enclave and Sehjra salient, but then failed to recapture Husainiwala from the north. The IAF had the ability to destroy the aggressors in Husainiwala and Fazilka, but it is doubtful if they were tasked. The opportunities were missed by 11 Corps, which had several formations and armour to recapture lost territory.

Air War in the West

The IAF flew about 4,000 sorties in the west12, which meant less than 10 sorties per squadron per day, on an average. Canberras were used only at night. AN 12s were also modified to be used as bombers. After intense fighting in the first few days, the PAF withdrew to bases in depth, to conserve their strength for a long-drawn war. Yet, the PAF continued to attack Indian airbases and troops throughout the War. PAF Sabres were able to attack the Indian port at Okha and inflict considerable damage. IAF bombers attacked Skardu airfield on 17 December.

The IAF flew about 130 sorties a day, ostensibly in support of the land battle. In an article, 1971 Air War: Aims and Objectives, published in the IDR on 29 Oct 2016, AVM AK Tiwary has stated that the tasks of the three Services were decided jointly before the war, but the question is: who selected the targets to be attacked, and whether the Army was consulted or even informed of the same. In another article 1971 Air War: Battle for Air Supremacy dated 15 Nov 2017, AVM Tiwary has explained why close air support could not be provided in the Eastern theatre13, but why better close air support was not provided in the West, is not clear. The Army must make it clear that sorties in support of the land battle must be planned in consultation with the formations in contact, divisions and below.

Once the situation stabilised in the first few days of war, Western Command should have planned not only to recapture Husainiwala and territory in Fazilka sector, but also to annihilate the aggressors. After 10 December resources should have been concentrated for recapture of Chhamb and Dewa. Western Command had adequate forces to execute all these tasks even simultaneously. In the Akhnur Sector there were 52, 68, 191 Bdes (not counting 28 Inf Bde) and Jammu had 19, 36, 162, 168 and 323 Inf Bdes. In addition 33 Inf Bde was idle at Poonch. Armour in the two div sectors were 9 H, 72 Armd Regt, CIH, 8 Lt Cav and 16 Cav, besides one infantry battalion (Mechanised). There was adequate arty and the IAF already had a favourable air situation and hundreds of aircraft for ground attack.

Recce missions, flown by the IAF, tried to locate Pak strategic reserves, but could not14. Other Intelligence agencies were equally ignorant. From the war accounts

it is clear that the situation in Pakistan was no better. In the fog of war, HQ Western Command, as well as the Army HQ kept expecting Pakistan to launch 2 Corps in south Punjab despite the air situation not being in its favour. Consequently, Western Command kept powerful forces of armour and infantry idle, while Pakistani troops continued to hold Indian territory in various sectors. The Army HQ even moved 50 Para Bde and some armour from the East, but Western Command kept them idle in the West.

As a lesson from history, one would recall how a critical situation had developed in the rear of the German Army Group South in Russia, in February 1943. Even during that most serious crisis, FM von Manstein had seen the possibility of a counter stroke which was delivered by mid-March 1943, to destroy several Russian armies. The least we can do is to learn lessons.

Sind

In the desert, 11 Division fought across the border, throughout. 12 Division’s plan of attack towards Rahimyar Khan, was scuttled by the Pakistani limited offensive at Laungewala. The Division re-deployed to defeat this aggression, with the help of the Air, but then could not reorganise, for a riposte. A few Hunters placed at Jaisalmer, completely destroyed the Pak armour. Unlike OC 4 TAC at Udhampur, the Group Capt at Jodhpur kept asking the Army for more targets to utilise the sorties available.

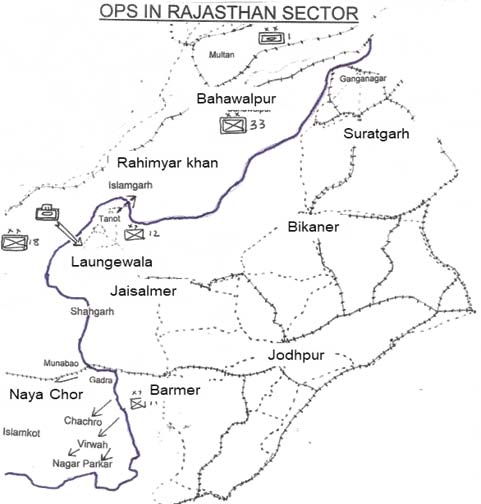

Operations in Rajasthan

Maritime Operations

As the Land-Air battles progressed on the Western Front, the Western Fleet of the Indian Navy dominated the Arabian Sea. The Pakistan Navy had retained most of its resources in the West. They had three Daphne class submarines, which were the most modern conventional submarines at that time. The PN was prevented by the IN and the IAF from attacking Indian ports.

CENTO was conducting an exercise in the North Arabian Sea from end November to first week of December 1971; but the IN planned its operations to avoid them skillfully and attack Karachi port twice during the war15.

Fast missile boats were accompanied and supported by other fast ships. Effective IAF attacks on Karachi airbases prevented maritime recce by F 86s at Karachi. The two Naval attacks succeeded in sinking a number of PN ships and some merchant vessels. About half the Pakistani oil reserve was destroyed in the combined attacks. PN vessels were forced to remain in harbours thereafter.

The IN intercepted Pakistani ships. One ship flying the flag of Philippines was brought to Mumbai. A Dhow bringing contraband gold to Karachi was captured. After the war, the gold was returned to Dubai.

The PN lost one submarine, two destroyers, seven gunboats, one minesweeper, three patrol craft and 18 other vessels. The IN lost one anti-submarine frigate, INS Khukhri, and one shore-based Alize aircraft during the war16.

After the surrender at Dhaka on 16 December, the PM announced a unilateral ceasefire in the West, which was initially rejected by the Pakistani President, but accepted next day. Should we have prolonged the war to recapture all territories lost, is an interesting question which can be debated.

This is the story of the war in the west, with many successes, a few losses, and several missed opportunities. The Indians lost a large number of men in numerous battles. As we salute them 50 years later, we owe it to them to learn all possible lessons from this war, that amazed the world.

IMPORTANT LESSONS FOR INDIA

Selection and Maintenance of Aim is a principle of war. While the Armed Forces achieved the overall aim of creating Bangladesh to return the refugees, the Western Command could not defend its complete territory. Capture of territory elsewhere, does not compensate for the loss.

Initial objectives for attack must be selected with greater deliberation, when we have the initiative and there are no constraints of time or resources. The objectives must result in overwhelming success with negligible casualties; which must raise morale of own forces. Morale is a principle of war.

The crying need is for synergy – between the Services, as well as within each Service. The Generals, Air Marshals and Admirals must learn to utilise all their resources optimally during war. It is astonishing to note that on 06 December even the Army DMO speaking to the DCAS proved futile to get more sorties for Chhamb. The matter was then raised to the Prime Minister before the CAS ordered increase of air effort to be provided to Chhamb. With the appointment of a CDS, it is hoped there will be better synergy in future wars.

The armed forces must make optimal use of the resources available in the three Services. To be able to do this, there is a need for better interaction within the Services so that the resources available are known to other services as well.

Signal intercepts provided excellent information about the adversary in the East; but formations in the West remained comparatively blind. There is a need to exploit technology to greater advantage.

Senior officers in all the Services, cannot wish away the fog of war. Commanders who wait for cut and dry Intelligence inputs to act, have little chance of fortunes of war favouring them. For this, officers must be trained to function in the ‘grey zone’ and to take risks.

Generals must realise that execution of plans prepared over long periods of peace, do not require brilliance. Commanders must learn to deal with adversity and to seize opportunities that arise in war.

In war, losses are inevitable. However, as soon as areas are lost, plans must be prepared to recapture these. This must be the most important task for all commanders in chain, right to the top, since only senior formation commanders can re-create reserves from not so active sectors. Commanders must plan to annihilate enemy forces that intrude into Indian territory. In 1971, the IAF had that capability, but it was not utilised.

There is need to increase interoperability between offensive and defensive formations. Generals must learn to make optimum use of all their resources in time and space, in war.

In most IAF accounts of the war, one finds excessive stress on number of kills and losses on the two sides. While these are important, the need is to measure success in the execution of each task allotted, such as counter air operations, air defence, close support to the Army and the Navy, recce, air photo coverage, transport and helicopter support. The tasks of support to the other Services must be to the complete satisfaction of the other Services.

Conclusion

Indians are proud of the three Services that won a magnificent victory in 1971. A few lacunae are inevitable in every war. These must be analysed and lessons learned for the future.

Notes

Information quoted in this article, has been collected from several sources. The author too participated in this war. Since there are minor variations in the data given in different books, the author has largely quoted information from the book, The India – Pakistan War of 1971, published by the Ministry of Defence.

- SN Prasad and UP Thapliyal, The India – Pakistan War of 1971, Natraj Publishers, Dehradun 2014, p 206.

AVM AK Tiwary, https://www.indiandefencereview.com/spotlights/1971-air-war-battle-for-air-supremacy/, 15 Nov 2017

2. Prasad and Thapliyal, The India – Pakistan War of 1971, pp 372, 374 and 392.

Naval Operations During the 1971 War – A Retrospect, by Team Salute January 22, 2015.

3. Prasad and Thapliyal, The India – Pakistan War of 1971, p 376 and 393.

Naval Operations During the 1971 War.

4. Prasad and Thapliyal, The India – Pakistan War of 1971, p 206.

5. ibid, p 206

Naval Operations During the 1971 War.

6. Maj Gen AJS Sandhu, _Battleground Chhamb: The Indo-Pakistan War of 1971, Manohar Publications, New Delhi. p 105.

https://indianairforce.nic.in/content/1971-ops.

7. Prasad and Thapliyal, The India – Pakistan War of 1971, p 141.

AVM AK Tiwary, Indian Air Force in Wars, p 197. AVM Tiwary’s figures are 450:288 (later changed to 267).

8. Maj Gen AJS Sandhu, Battleground Chhamb,_pages 126 to195 cover the battle in detail.

9. Maj Gen AJS Sandhu, Battleground Chhamb, pp 184, 281.

10. ACM PC Lal, My Years with the IAF, Lancer Publication, New Delhi, 1986, pp 232 to 234

11. Maj Gen AJS Sandhu, _Battleground Chhamb_,_p.184,281. The officer was Air Cmde Aman Ullah Khan, PAF

12. https://indianairforce.nic.in/content/1971-ops.

Prasad and Thapliyal, The India – Pakistan War of 1971, p 235.

AVM AK Tiwary 1971 War: Military Aims and Objectives published in Indian Defence Review, 29 Oct 2016

13. https://www.indiandefencereview.com/spotlights/ 1971-war-military-aims-and-objectives/2/.

Prasad and Thapliyal, The India – Pakistan War of 1971, p 235.

13. https://indianairforce.nic.in/content/1971-ops100s of sorties.

Prasad and Thapliyal, The India – Pakistan War of 1971,p 221-228.

Tiwary, https://www.indiandefencereview.com/spotlights/ 1971-air-war-battle-for-air-supremacy/.

14. Prasad and Thapliyal, The India – Pakistan War of 1971, p 229.

15. ibid, p 248, 249, 253.

Naval Operations During the 1971 War.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indo-Pakistani_Naval_War_of_1971.

16. Naval Operations During the 1971 War.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indo-Pakistani_Naval_War_of_1971.

Prasad and Thapliyal, The India – Pakistan War of 1971, p 485, 486.

A very well compiled brief of the war sir!!

Great insight and an excellent portrayal of the war.

The narrative is very well explained.

Very well brought out sir

A very fine articles. Well written.

Please see if these articles are of any interest to you:

https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/indias-chief-defense-staff-s-suchindranath-aiyer/

https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/how-would-theatre-commands-work-under-chief-defense-staff-aiyer/