India’s role in the world order has been gradually expanding. From its fledging origins in the early-50s, to the exalted perch at which it finds itself now, there has been a virtual inversion of maritime status and power equations. Historically, Indian maritime forays into the outside world were driven by commerce and culture. There was a strong civilisational element to maritime excursions. Even the culturally affiliated ‘Indian’ kingdoms that came to be established in Southeast Asia were a result of the strong trade and cultural links shared with their Indian counterparts. The fact that they were completely independent — neither colonies, controlled from India, nor bearing any allegiance to any ruler in India — is illustrative of the ‘nuanced’ and balanced nature of our naval ambitions.

Click to buy: Transition to Guardianship: The Indian Navy 1991-2000

Contrary to what some western historians would have us believe, there was most definitely a deliberate and well thought out methodology to our maritime endeavours. India doubtless, sought to be a great nation; but not by conquest or plunder — instead by trading and cooperation.

“One mountain should have just one tiger” “” Chinese proverb

In time, a realisation followed that for trade to flourish it was imperative to ensure safety through the sea lanes. This impelled the Indian Navy into taking a more assertive role in safeguarding the EEZ and SLOCs. In all operations undertaken subsequently, it displayed greater proactivism. It was, however, not in the least hostile or confrontationalist in either intent or approach. On display, was a clear demonstration of the willingness to uphold fundamental principles of peaceful co-existence that was the guiding spirit behind all our maritime engagements.

Strategic Perspective on the Navy’s Emerging Role

In the 90s, for the first time after independence, Defence policy focussed on the larger context as to whether the military’s role was to defend national territory and sovereignty against external aggressions or to establish a military presence in the region to safeguard national interests?

For the major part of India’s post-independence period, the country had opted for an ostensibly defensive posture; the major preoccupation being the goal of rapid socio–economic development of the country and the concern for containing defence expenditure. The deterrent capability of our Defence Services, built up over the years, eroded considerably, even as it resulted in long stretches of comparative peace, enabling the nation to concentrate on its task of technological, economic and social advancement.1

It had an inevitable effect on the build-up of naval force levels. Sea control operations, based on the principle of continuously monitoring and controlling activities in a given maritime area over a period of time, required covering a theatre of operation extending over thousands of square kms. With depleted combat forces, it just didn’t seem a practical possibility. The navy perceived this as a disabling factor that would have a disrupting effect in its being able to secure the SLOCs (that it saw as a prime responsibility). It, nonetheless, took proactive measures with its existing force strength to ensure that safety in the sea lanes was not compromised.

Operations Undertaken to Safeguard the Sea Lanes

The efforts of the Indian Navy to safeguard the sea-lanes in the 90s decade could be broadly categorised into four types of naval operations — Humanitarian, Low Intensity Conflict (LIC) operations against illegal and undesirable elements, Anti-Piracy and Deterrent.

“¦mission of the Navy in the future would be defined by a new, more profound consciousness of the seas and the security of the sea lanes”¦

Humanitarian. The United Nations Operations in Somalia between 1992 and 1994 in which India participated. It was a first for the Indian Navy, to be participating in an operation of such scale and magnitude.

Low Intensity Conflict (LIC). Three prolonged ‘round-the-clock’ LIC operations against a mixed bag of malevolents:

- Operation Tasha in the confined waters of the Palk Bay which aimed to interdict the illegal transit of men and material between the LTTE Tamil secessionists in northern Sri Lanka and their sympathisers in Tamil Nadu.

- Operation Swan off the west and northwest Arabian Sea coast of India which aimed to interdict Pakistani terrorists smuggling explosives, weapons and ammunition in fishing vessels to religious extremists in India.

- Operation Leech and its successors in the Bay of Bengal which aimed to interdict the smuggling of weapons, narcotics and explosives from the bazars of Southeast Asia to coastal destinations on the eastern rim of the Bay of Bengal, for onward conveyance and delivery to secessionist militants who were combating Indian troops in the north-eastern states of India.

Anti-Piracy. Operation Rainbow, a joint operation with the Coast Guard in 1999, which resulted in the rescue of the hijacked merchant vessel Alondra Rainbow.

| Editor’s Pick |

Deterrent. Operation Talwar in June 1999, wherein the Indian Navy enhanced security measures as a result of the Pakistani aggression in Kargil.

Operations Tasha, Swan and Leech demonstrated the ability of the Indian Navy and naval personnel to protect the EEZ not just from an economic but also a security perspective against malevolent forces operating in our territorial waters.

Operation Rainbow marked the first of the Navy’s operations against the scourge of piracy, which has reared its ugly head again in the Indian Ocean.

Operation Talwar was the first instance of the Navy supporting land operations in a predominantly territorial war. It also highlighted the effectiveness of Naval deterrence in such conflicts.

The sustained proficiency of our men and the reliability of material as demonstrated in these operations boosted the confidence of the Indian Navy to undertake blue water operations in distant waters.

By 2000, based on the experience in the above operations, India’s zone of peaceful maritime influence had crystallised from the distant Horn of Africa to the Strait of Malacca and to the Tropic of Capricorn in the south.

But there was also increased awareness that the mission of the Navy in the future would be defined by a new, more profound consciousness of the seas and the security of the sea lanes; that it would need the revision and redrafting of the framework of the conventional role of the Navy; that new geopolitical realities that shape our world would need careful and thoughtful consideration to truly comprehend the real threats that the future hold for us.

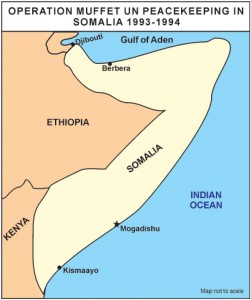

Operation Muffet in Somalia 1992 to 1994

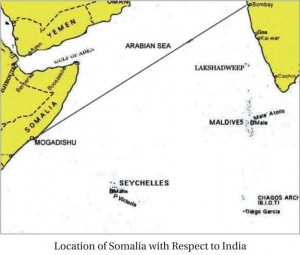

The Somalia operation between December 1992 and December 1994 was the Indian Navy’s first ever overseas deployment in support of United Nations Humanitarian Relief Operations.

The international community began to send food supplies to halt the starvation, but vast amounts of food were hijacked and brought to local clan leaders, who routinely exchanged it with other countries for weapons.

In the late 80s, a civil war had broken out in Somalia after a military campaign against the incumbent government, that saw serious clan-based fighting between rival factions and large part of the country being occupied by the forces of dissidence.

In September 1991, severe fighting broke out in Mogadishu, which continued in the following months and spread throughout the country, with over 20,000 people killed or injured by the end of the year. Agriculture was destroyed and it led to starvation in large parts of Somalia. The international community began to send food supplies to halt the starvation, but vast amounts of food were hijacked and brought to local clan leaders, who routinely exchanged it with other countries for weapons. An estimated 80 percent of the food was stolen. These factors led to even more starvation, from which an estimated 300,000 people died, and another 1.5 million people suffered between 1991 and 1992. By 1992, almost 4.5 million people, more than half the total number in the country, were threatened with starvation, severe malnutrition and related diseases. The magnitude of suffering was immense. Some 2 million people, violently displaced from their home areas, fled either to neighbouring countries or elsewhere within Somalia. All institutions of governance and at least 60 per cent of the country’s basic infrastructure disintegrated.2

The UN Administered Humanitarian Operations

Against this background, in January 1992, the Security Council unanimously imposed a general and complete arms embargo on Somalia. In March 1992, agreements were signed between the rival parties in Mogadishu resulting in the deployment of United Nations observers to monitor the cease fire. The agreement also included deployment of United Nations security personnel to protect United Nations personnel and humanitarian assistance activities.

However, in the absence of a government capable of maintaining law and order, relief organizations experienced increased hijacking of vehicles, looting of convoys and warehouses, and detention of expatriate staff.Operation PROVIDE RELIEF. The operation began in August 1992, when the White House announced that US military transports would support the multinational UN relief effort in Somalia. Ten C-130s and 400 people were deployed to Mombasa, Kenya during Operation Provide Relief, airlifting aid to remote areas in Somalia, to reduce reliance on truck convoys. The Air Force C-130s delivered 48,000 tons of food and medical supplies in six months to international humanitarian organizations trying to help the over three million starving people in the country.

However, in the absence of a government capable of maintaining law and order, relief organizations experienced increased hijacking of vehicles, looting of convoys and warehouses, and detention of expatriate staff.Operation PROVIDE RELIEF. The operation began in August 1992, when the White House announced that US military transports would support the multinational UN relief effort in Somalia. Ten C-130s and 400 people were deployed to Mombasa, Kenya during Operation Provide Relief, airlifting aid to remote areas in Somalia, to reduce reliance on truck convoys. The Air Force C-130s delivered 48,000 tons of food and medical supplies in six months to international humanitarian organizations trying to help the over three million starving people in the country.

Click to buy: Transition to Guardianship: The Indian Navy 1991-2000

Operation RESTORE HOPE. Ops Provide Relief proved inadequate in stopping the massive death and displacement of the Somali people (500,000 dead and 1.5 million refugees or displaced). In December 1992, the US assuming the unified command in accordance with resolution 794(1992) launched a major coalition operation, RESTORE HOPE to assist and protect humanitarian activities.

India’s Participation in UN ‘RESTORE HOPE’

By the end of 1991, the situation in Somalia was grave. The international relief efforts were stymied by the fact that, while food supplies were reaching Somalia, armed gangs of the two warring factions looted food shipments and food convoys and prevented food from reaching the starving. There was urgent need to protect food deliveries from the looting gangs.

An American led multinational force comprising 35,000 troops from several countries was pressed into service. But more assistance was needed and an international appeal was sent out for other countries to join.

In December 1992, India decided to join the United Nation sponsored international effort “Operation RESTORE HOPE”. India’s contribution was a brigade of about 2000 troops and a naval task group of three ships.

The Indian Naval involvement in the UN Operation ‘RESTORE HOPE’ can be described in three segments:-

- Op MUFFET

- Op SHIELD

- Op BOLSTER

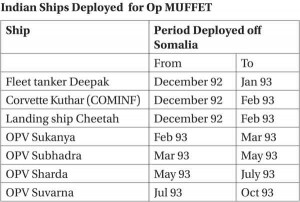

Operation MUFFET

Consequent to the Cabinet Committee on Parliamentary Affairs deciding in favour of participating in the humanitarian efforts, a task force comprising three ships was dispatched to Somalia. IN Ships Deepak, Kuthar and Cheetah constituted the task group and was commanded by Commodore Sampath Pillai who was designated as Commodore Indian Naval Forces (COMINF).

An Indian Liaison Organisation (INLO) was set up with LtCdr Hari Kumar as the first INLO, at the Coalition Joint Task Force (CGTF) HQ located in the US Embassy building to liaise with UNITAF, UNOSOM and NGOs. The team consisted of one officer, three MARCOs and few others. The liaison officer represented the Indian forces at all meetings, intelligence briefings and functions at the CGTF HQ and was the nodal point for liaison between the liaison cells set up by 22 countries.

Instances of Direct Indian Participation

Search and Rescue by Sukanya. On 03 February 1993, INLO was approached by representatives of World Food Programme (WFP) and CARE to intercept a CARE chartered ship MV Remorra Bay which was carrying 350 tons of sugar and 15 tons of wheat flour. The ship had lost radio contact since 28 January 1993 off the coast of Merka. It was a practice of the Masters to unload the aid material at enormous profit at other ports (like Brava, Merca) and blame it on attack in the high seas by pirates. INS Sukanya sailed with representatives of WFP and CARE to intercept the merchant vessel. At 1715 hrs, MV Remorra Bay was sighted and a Gemini was lowered with an armed boarding party. By then, the merchant vessel had resolved the engine problem that was due to fuel contamination.

Assistance for Humanitarian Aid. UNICEF sought IN assistance for the transportation of humanitarian aid between Mogadishu, Kismayo and from Mombasa. These stores, till then were airlifted and it was found uneconomical. INS Sukanya made two trips to Mombasa (10–20 Feb & 03–11 Mar). In addition, cargo was also carried for the Irish agency CONCERN and for UNOSOM.

Role in Transition from UNITAF to UNOSOM

The IN participation in the UNITAF ‘Op RESTORE HOPE’ was restricted to patrolling and transporting of UN Stores. The UNITAF operations were terminated on 04 May 1993 (17 December 1992 to 04 May 1993). However, the humanitarian assistance in Somalia continued as United Nations Operation Somalia (UNOSOM).

| Editor’s Pick |

When UNITAF was handed over to UNOSOM II, the IN was requested for officers to assist the new HQ till permanent staff arrived. This was readily acquiesced and LtCdr NNS Manian, LCdr KK Pandey and LCdr Hari Kumar were assigned to the Transition Headquarters in March 1993. It was the first time in the history of the IN that naval officers wore the Blue Beret and worked on an UN mission.

The naval representation from ashore was withdrawn in June 1993 and the IN ships were withdrawn by end 1993. The performance of the Navy and the troops deployed for ‘Operation MUFFET’ made a conspicuous geopolitical impact.

Operation SHIELD and Operation BOLSTER

‘Operation SHIELD’ (06 to 11 December 1994) was the name given to de-induction of troops from Kismayo and ‘ Operation BOLSTER’ (12 to 23 December 1994) concerned the de-induction of troops from Mogadishu.

The De-Induction

By the middle of 1994, the Brigade in Somalia, had completed its tenure of duty, and needed to be de-inducted. De-induction of UN forces and their equipment required offshore and air support, but this was not readily forthcoming. India therefore chartered merchant ships and an airliner.

The Navy deployed two frigates and a tanker for the de-induction operation. Each frigate had two Seaking heavy helicopters. The mission was assigned to the Western Fleet in the middle of November 1994, and the Western Fleet Commander was designated Task Force Commander. Ganga and Godavari sailed from Mumbai on 28 November and Shakti departed 26 November 1994, headed for Kismayo.

Ops — SHIELD

The Indian Navy’s mission was “to provide naval presence and terminal support for smooth deinduction of Indian Army troops from Kismayo, Somalia, including Naval Gun Fire Support, where-so-ever feasible”. On arrival off Kismayo on 06 December 1994, all helicopters were flown in formation over the town in a show of force. The Naval Task Group was assigned to:-

- Cover the de-induction of 1 BIHAR Battalion Group from Kismayo.

- Provide helicopter support for the evacuation of the rearguard elements.

- Provide air-surveillance and close weapon support during withdrawal of armour from airport to seaport and their loading on merchant ships.

- Provide hospital ship facility on board Godavari.

The Battalion Commander of 1 BIHAR handed over the airport to the City Council and the troops guarding the airport, regrouped, and moved cross-country to the seaport.

Phases of De-induction from Kismayo. By 06 December 1994, the 1 BIHAR Battalion, deployed in Kismayo for the UN controlled humanitarian and relief operations, had withdrawn from the town area and had concentrated in three areas namely Kismayo International Airport, Marolles Complex and Kismayo Seaport. The progressive de-induction of the troops began by their airlift to Mogadishu. Equipment packed in containers, along with armour and vehicles were also withdrawn to the seaport.

Phase I — Deinduction from Airport. The first phase commenced on 07 December 1994 with two L-100 aircraft arriving from Mogadishu for de-induction of the bulk of troops. The Battalion Commander of 1 BIHAR handed over the airport to the City Council and the troops guarding the airport, regrouped, and moved cross-country to the seaport. The Naval ships provided NGS while helicopters provided air surveillance and close weapon support all along the route for the withdrawing men and armour. The show of airpower with four armed helicopters providing route cover prevented the Somali militia from closing on the withdrawing troops. While the operation was in progress, two merchant vessels, namely, MV Free Wave and MV Vinnitsa arrived at Kismayo and anchored close to the IN ships.

Phase II — Deinduction from Marolles Complex. The Marolles complex, a facility under the control of Indian troops, was to be handed over to the Somalis. Situated at the northern end of the causeway between the mainland and the seaport, the complex was planned for vacation followed by a quick retreat of troops and armour to the Hamburger Hill/Seaport. As the operation got underway, a large number of armed Somalis converged at the checkpoint of the complex. To prevent any misadventure, all four naval helicopters were airborne and positioned to cover the approaches. Soon after, the Battalion Cdr handed over the Marolles Complex to the representative of the City Council, the armour and troops withdrew to the Hamburger Hill. However, as expected, no sooner had the complex been vacated, the locals broke into the area and looted the place.

Phase II — Deinduction from Marolles Complex. The Marolles complex, a facility under the control of Indian troops, was to be handed over to the Somalis. Situated at the northern end of the causeway between the mainland and the seaport, the complex was planned for vacation followed by a quick retreat of troops and armour to the Hamburger Hill/Seaport. As the operation got underway, a large number of armed Somalis converged at the checkpoint of the complex. To prevent any misadventure, all four naval helicopters were airborne and positioned to cover the approaches. Soon after, the Battalion Cdr handed over the Marolles Complex to the representative of the City Council, the armour and troops withdrew to the Hamburger Hill. However, as expected, no sooner had the complex been vacated, the locals broke into the area and looted the place.Phase III. By the end of the second phase, the equipment of the 1 BIHAR Battalion was accumulated at the Seaport and the 208 troops had fallen back to Hamburger Hill. The third phase began with MV Freewave commencing loading on 08/09 December. The loading of MV Vinnitsa commenced the next day. By 11 December 1994, the vessels had completed loading and set sail for Mogadishu.

Click to buy: Transition to Guardianship: The Indian Navy 1991-2000

Phase IV — Deinduction of Rearguard Troops. Phase IV was the most crucial part of the de-induction since local militia were vying with each other to take control of the seaport and were intent on looting large quantities of fuel and rations of the UNOSOM, which had been abandoned at the seaport. As the two merchant vessels set sail with Indian troops, the naval contingent swung into action. With the MARCOs providing cover on ground, helicopters were stationed over Hamburger Hill and above the Bay (between the mainland and seaport) to provide close weapon support and check infiltration by boats. One Seaking was positioned on Hamburger Hill to transfer baggage of the rearguard, while two others guarded the southwest side of the seaport to ensure safe recovery of the rearguard. At the end of the phase on 11 December 1994, 203 soldiers had been de-inducted to Mogadishu. ‘Operation SHIELD’ was a success without any casualties.

Op BOLSTER

The task force from Kismayo arrived at Mogadishu on 12 December 1994, by which time the Indian and other UNOSOM troops had concentrated around the Mogadishu airport. The cargo, along with three BMPs of the Indian contingent to be shipped, had already been positioned at the port for evacuation and was being guarded by an Egyptian contingent. As soon as the task force arrived, loading of cargo into the merchant ships began. MV Vinnitsa was the first ship to complete loading on 13 December and soon moved out. MV Freewave completed loading and sailed out on 16 December, while MV Atlantic Lily departed on 18 December. In the meanwhile, units of the task force continued their vigil of the port until the last soldiers were repatriated by chartered ships and aircraft.

But neither relief nor support was forthcoming from the Western members of the UN Security Council.

The Indian Naval Task Force was providing air cover and patrolling the coastline till the last UN chartered flight left Mogadishu on 23 December 1994. With the departure of the chartered flight, ‘Op BOLSTER’ was terminated and the Task Group proceeded to sea on 23 December from Mogadishu.

Rear Admiral RN Ganesh, recalls:3

“In 1992, the UN Security Council intervened in Somalia to restore order and stability after the severe humanitarian crisis caused by internal war in that country. A multi-national Task force was led by the US (initially named UNITAF and subsequently UNOSOM). The Indian Navy participated in the earlier phase which was mainly a logistic operation.

An Indian Brigade was despatched to Somalia in 1993 as part of the UN Forces to restore stability and the rule of law. The US launched a mission to terminate general Aidid and his senior officers. The mission backfired badly and the notorious “Blackhawk Down” incident resulted in the death of 18 US soldiers and ignominy for the US forces. Within 3 days, America abandoned Somalia. Thereafter, conditions in Somalia deteriorated steadily and the Security Council ordered withdrawal of UN forces from Somalia.

By the middle of 1994, the Indian Brigade, which had completed its tenure of duty with honour, was overdue to be relieved. It was obvious that the withdrawing UN forces would require offshore and air support. But neither relief nor support was forthcoming from the Western members of the UN Security Council.

This was the background against which the Indian Government decided to dispatch a Naval Task Force for the extraction of the Indian Brigade from Somalia.

This was the background against which the Indian Government decided to dispatch a Naval Task Force for the extraction of the Indian Brigade from Somalia. The task was assigned to the Western Fleet in the middle of November 1994 and the Fleet Commander was designated the Task Force Commander. Two FFGs (Guided missile frigates) Ganga and Godavari and a fleet tanker Shakti were selected to form the Task Force, which sailed from Bombay on 28 November 1994 and set course for the West Coast of Africa.

The Task Force arrived off Mogadishu on the 06 December and established radio contact with the Headquarters of the 61 Independent Brigade. Two Indian battalions, which had been deployed in the interior, had concentrated on Mogadishu, but the 1 BIHAR was still in the Kismayo area, some 250 kilometers to the south. The situation in Mogadishu was under control as the air and seaports were well in the area held by the remaining UN forces. In Kismayo, however, the Indian forces had no support and they would have to be prepared to carry out a fighting withdrawal.

On 06 December, the Task Force arrived off Kismayo. The Brigade Commander and his senior officers were ferried aboard the flagship Ganga for a planning conference. It was decided that 1 BIHAR would withdraw to the seaport under support of a squadron of its T-72 tanks, and with a rear guard of about forty chosen men. The port was dominated by a hill feature (it was called “Hamburger Hill” by the Americans, and was named “Malabar Hill” by the Indian Task Force staff). The rearguard echelon of 1 BIHAR would take position on Malabar Hill and control the access to the port. The Seaking helos from the Task Force would be deployed on armed reconnaissance to keep at bay the pursuing forces of the Somali warlords with their gun-fitted lorries, locally known as “technicals”. The electronic warfare capability of the ships was used to intercept messages between the Somali militia and keep track of their location. Meanwhile, the ships of the task force patrolled off the port, keeping the vital positions of the area constantly in their gun sights.

| Editor’s Pick |

On 11 December, the Battalion withdrew as planned into the seaport and embarked on the Ro-Ro ships that had been chartered for the purpose, along with their vehicles, arms and equipment. At dawn on 11 December, the Indian chartered ship sailed from Kismayo Harbour for Mogadishu and in a swift and smooth operation, the remaining troops were helo-lifted from Malabar Hill in two sorties to the ships of the Task Force, while a third helo orbited overhead providing cover for the evacuation. Operation SHIELD had been completed successfully without a shot being fired.

The Task Force arrived off Mogadishu on the 12 December, and remained till 23 December 1994, when the last soldiers were repatriated by chartered ships and aircraft, and the naval units sailed back to Mumbai.

These operations had a strong impact in international military circles. India, a developing country, had shown the will and the capability to protect its interests across the ocean, off another continent, whereas more developed countries had failed to honour their commitments.

In many ways, Operations SHIELD and BOLSTER heralded a new maturity and purposefulness on the part of the naval and the civilian leadership in the exploitation of sea power in the extended areas of our interest.

The Pakistani Brigade Commander said wistfully to me: “kash hamare navy walon bhi aisa karte!”

The Indian Army succeeded because it went in with its boots on, and did not fight shy of going into the interior where required. The US effort on the other hand had been from the safety of the air and without any forces on the ground they were unable to establish their presence with authority.

The Army were deeply appreciative, however, and there were articles by them of the way our “boys in white” came to rescue them from a sticky situation. The Pakistani Brigade Commander said wistfully to me: “kash hamare navy walon bhi aisa karte!” (“I wish our Navy had also done likewise”). A couple of months later, the Journal of the Royal Artillery published a laudatory article on the important role played by the Indian Navy and the lessons it had for the western powers.

Col Anil Shorey4 recalls:

“As our time came to return to India after nearly 15 months, the Somali clans grew more and more belligerent throughout the mission area, including Kismayo, the second largest coastal town of Somalia located 240 kilometers southwest of the largest town and capital Mogadishu. The Indian battalion, 1 BIHAR, was deployed there.

As the days for the final de-induction of the Indian brigade drew nearer, units in the hinterland chalked out plans to hand over respective charge to the local Somali authorities. While everything went smoothly in the hinterland, the battalion at Kismayo was not so lucky.Intelligence reports received by the battalion at Kismayo indicated that some of the Somali clan members intended to coerce 1 BIHAR to leave all its weapons and equipment behind.

As the days for the final de-induction of the Indian brigade drew nearer, units in the hinterland chalked out plans to hand over respective charge to the local Somali authorities. While everything went smoothly in the hinterland, the battalion at Kismayo was not so lucky.Intelligence reports received by the battalion at Kismayo indicated that some of the Somali clan members intended to coerce 1 BIHAR to leave all its weapons and equipment behind.

In case this was not agreed to, these would be taken by force. With this input, our hopes for a smooth and early exit from Somalia grew dim.

What the Indian brigade needed was a naval task force. But that seemed elusive since many Western countries were more inclined to ‘wait and watch’ the Somali situation rather than put their fleet to sea for the convenience of Third World contingents.

Click to buy: Transition to Guardianship: The Indian Navy 1991-2000

However, towards the end of November 1994, the Indian Government decided to send a naval force to Somalia. Accordingly, an Indian naval task force of two frigates and a tanker, reached Kismayo on 6th December. For the officers and men of the Indian brigade, particularly those of 1 BIHAR and an independent squadron of 7 Cavalry (comprising T 72 tanks) based at Kismayo, it was a moment of pride, elation and relief to see their own, impressive and Indian made naval ships coming to assist them during the crucial de-induction.

This operation succeeded in sending signals across Somalia and the world that the Indians meant business in preserving the property and integrity of its brigade in Somalia during de-induction.

The Brigade Commander flew into Kismayo from Mogadishu with a few Brigade staff officers. We were airlifted by naval Seaking helicopters to INS Ganga. A coordination conference was held where the operational modalities and support to be provided by the task force were discussed.

Op SHIELD, de-induction of troops from Kismayo started on the following day. The process went about peacefully and the crucial transition of Indian-held UN assets (excluding Indian weapons and equipment) between 1 BIHAR and local Somalis was executed at the Kismayo airport and seaport.

To ensure the safety of Indian troops, the Indian naval fleet provided various types of support — aerial logistics, fire support from integral helicopters, ship-to-shore standby fire support and signal communications.

Around this time reports came in about militant groups, belonging to three different clans, planning to force their way towards the seaport from three different directions. Gunshots could be clearly heard from the direction of Kismayo town. We soon learnt through intercepted wireless communication that Somali clan members were looting, at gunpoint, a Non Government Organisation’s warehouse holding food grain.

Valuable experience was thus gained in operating integral helicopters for prolonged durations daily for air surveillance and recce.

At the Kismayo seaport, there was no major cause for worry as earmarked Indian troops, supported by tanks of 7 Cavalry squadron, were already deployed at vantage positions. Effective roadblocks had also been set up to ensure a smooth de-induction of Indian troops without external interference. As the de-induction progressed, the tanks and bulk of Indian troops at various check-points were to fall back to the seaport for boarding various ships, leaving behind an effective rear-guard of 40 personnel of 1 BIHAR.

Regular armed sorties of the Indian Brigade’s Chetak and the Navy’s Seaking helicopters also deterred the belligerent Somali armed factions from coming closer to the seaport. Simultaneously, the Indian naval ships had their weapons trained on to different land objectives and their electronic warfare equipment on board not only jammed militant radio frequencies but also selectively monitored their command and control communication channels, which provided invaluable information to Indian forces.

However, the most striking aspect and the grand finale of the entire Kismayo operation was the rear-guard action performed jointly by the troops of 1 BIHAR and the Indian naval task force.

| Editor’s Pick |

After ensuring that no interference took place by Somali clan members during de-induction, the 40-odd troops of 1 BIHAR, forming the rear-guard, converged at the strategic Hamburger Hill. This hill overlooked the Kismayo harbour from the north and also the main approach leading to it from Kismayo town. From here, they were lifted by naval Seaking helicopters and ferried to different ships of the task force.

On the night of 11/12 December, the task force weighed anchor and arrived at Mogadishu by the afternoon from where it supported the de-induction of the bulk of Indian troops. By 13 December, the final de-induction by air and sea became effective.

This operation succeeded in sending signals across Somalia and the world that the Indians meant business in preserving the property and integrity of its brigade in Somalia during de-induction. It also proved that India was capable of dealing with such contingencies which earlier had been the prerogative of the US and Western navies”.

Operational Significance of the Somalia Operations

Viewed introspectively, from a purely military perspective, the deployments between 1992 and 1994 were significant for several reasons:-

- They validated confidence in the Navy’s re-oriented operational philosophy of “Forward Deployment” in blue waters. This was in sharp contrast to the earlier compulsions of being tethered in the vicinity of homeports, to conserve operating hours of machinery/equipment and fulfil the twin objectives of economising fuel costs and lessening the problems of logistic support of imported machinery/equipment.

- The intrepid way the Navy’s unprotected helicopters (Seakings and Chetaks) carried out recce and air cover sorties was a revelation. Operating from their mother ships in turbulent winds at anchor, or patrolling close offshore in heavy seas, they also air-lifted troops during the de-induction of the Indian brigade in the very skies of Mogadishu in which Somali militants had shot down well-armed American helicopter gun-ships. Valuable experience was thus gained in operating integral helicopters for prolonged durations daily for air surveillance and recce.

- Equally valuable was the revelation of the ability of ship’s and their integral helicopters to operate for several months at a stretch hundreds of miles away from homeport and their shore-based maintenance facilities/expertise. This substantiated the reliability of indigenised naval equipment and machinery. It also corroborated the concepts that underlay the training reforms of the preceding decades.

The sustained proficiency of our men and the reliability of material boosted confidence for the Indian Navy’s blue water operations in distant waters. At the same time, it reinforced the vital need of more fleet tankers for such operations.

Lessons Learnt

Despite remarkable gains and the more than significant experience that it offered, there were important lessons to be learnt from the operation:-

- The operation brought home the dependence on tanker support, without which no progress would have been possible.

- The Navy realised that there were serious hazards of using helicopters in prolonged low intensity conflict in heavily congested urban areas.

- The difficulties of coordinating contingency plans between multinational forces assembled for UN Operations were also made clear.

Retrospect

Given the geo-strategic location of the Gulf of Aden through which thousands of merchant ships transit every year, Operation MUFFET yielded valuable insights. India, a developing country, had shown the will and the capacity to share in the protection of its SLOCs in its extended zone of maritime interest across the northern Indian Ocean, off another continent, as part of a multilateral UN task force.

The ability of ships to sustain prolonged operations for two years away from their homeports led introspective planners to conclude that India had extended to cover the SLOCs from the Horn of Africa in the northwest to the Straits of Malacca in the southwest.

From a national perspective, the operation was well received in all quarters. By all accounts the presence of our ships in the area earned considerable goodwill from the local population and facilitated the task of Army de-induction. In fact, the US Secretary of Defence expressed his appreciation and complimented the Indian Navy for their participation in the peacekeeping efforts.

For the Indian Navy, the operation, in its very essence, was a watershed and marked a new beginning for the Service. Apart from being a capability demonstrator and a confidence booster, it heralded the start of an era when the Navy could play a meaningful and effective part in international efforts in support of humanitarian operations. For the sheer range of experience in coordinated international action, that it provided the Navy with, Operation ‘MUFFET’ remains very significant.

For the Indian Navy, the operation, in its very essence, was a watershed and marked a new beginning for the Service. Apart from being a capability demonstrator and a confidence booster, it heralded the start of an era when the Navy could play a meaningful and effective part in international efforts in support of humanitarian operations. For the sheer range of experience in coordinated international action, that it provided the Navy with, Operation ‘MUFFET’ remains very significant.

Continued…: The Emerging Role of the Indian Navy in the New World Order – II

Notes:

- Excerpts from the Estimates Committee Report 1992–93.

- Refer to Reference Note, ‘Background of the Somalia Conflict’.

- Rear Admiral (later Vice Admiral) RN Ganesh commanded the Naval Task Force that was sent to Somalia to de-induct the Indian Brigade.

- Sainik Samachar, March 2006 : Extract of Col Anil Shorey’s article in which he recalls the Navy’s de-induction of his troops from Kismayo in December 1994.

Indian Naval Force ie COMINF was commanded by Commodore Sampath Pillai. & not Rear Admiral Sampath Pillai. He put on the rank of Rear Admiral only after the UNOSOM – II Opeeation was terminated. Just correct the write up please ?

Commander NNS Manian,NM,Gallantry, Retired

Ex Oprations Officer COMINF & Military Secretary to the Force Commander, UNOSOM- II (Lt Gen Civic Bir of Turkey.)

Indian Navy carried out the Survey of Kissmayu entrance channel & rendered safe for entry during the deployment for OPMUFFET.

The survey team worked under the overall supervision & guidence of Commander NNS Manian,NM.

Dear Readers, None of the Naval Officers & Sailors who took part in UNITAF Operation Restore Hope & UNOSOM-II Operations.

Got paid for their deputation to UN.

I am not sure why was it a NHQ decision or Indian Government decision?.

We created History that went unrecoganised.

So sad.

Commander NNS Manian,NM,Retired

Dear Admiral Hirsnandani Sir, Greetings of the Ssason. This is Commander NNS Manian, NM, Retd. I was in this operation as Commodore Commanding Indian Naval Force (COMINF’s) as Operation and Plans Officer & thereafter assigned to UNOSOM-II as Military Secretary (MS) to the then Force Commander Lieutenant General Civic Bir of Turkey..

I took part in this operation as Commander & not as Lieutenant Commander.

In addition to this I was instrumental if getting across to Nairobi without any travel documents whatsoever & get the spares lying in Air Cargo terminal single handedly to get the LST Operational for return to India.

I had sent an Article titled “Setting Course to Somalia” to DNT for publication in Naval Dispatch, I am not sure what DNT did with it.

If you need any first Hand knowledge of what we went through, you are welcome. My email ID nnsmanian@gmail.com

Thanks and regards.

Commander Nagasubramanian Nagaratnam,NM,Retired (01349R)