The global community has witnessed transformations in terror groups across the spectrum. These transformations can be attributed to various external changes that force the terror groups to change internally. For a commoner’s eye, these changes do not mean much. But if we are to study these changes, we would be better placed to appreciate the systematic thought process behind each and every change that takes place in terror groups. Terrorists have shown extraordinary intelligence by adapting business concepts like creating interchangeable missions, redefining organisational structures and forming strategic alliances to run their organisations efficiently. This paper attempts to study this important facet of managing “change” by terror groups effectively, which is akin to the process of change management and organisational dynamics in legitimate business enterprises.

The irony is that law enforcement efforts have proved to be counterproductive, forcing these groups to transform themselves into virtual networks and making it much harder to detect and disrupt them.

The external environment is one of the important variables that have posed serious challenges to many entities. While some have survived, many have perished. Many start-ups led by energetic entrepreneurs have failed to take off while some crash-landed after take off. But one business which has grown by leaps and bounds in spite of an adverse environment is “The business of terror.” It is quite surprising to observe that terror groups, by and large, have been successful despite being illegal, functioning with illicit finance and being manned by outlawed persons while many a legal entity, with lawful objectives, funded by legitimate means and managed by genuine businesspersons, has failed. It is this reason which makes it all the more imperative to study a terror group’s growth trajectory and its survival abilities in spite of facing a hostile environment with very demanding and challenging deliverables. A terror group derives its resilience from its networks and organisational structure, complemented well by innovative methods led by individual brilliance. However, recent developments in technology have also helped terror groups to be more resilient.

The study on how a terror group functions with respect to its key functions will throw a better light on the grey areas surrounding it. Terrorist groups have transformed and evolved, innovating in the process. Strategic alliances like mergers, joint ventures and partnerships through franchises act as force multipliers. Their innovative recruitment policies and people centric motivation methods are their core areas of strength. The groups have grown under the tutelage of their leaders, who have shown tremendous leadership abilities. Hypothetically, if Osama Bin Laden and Vellupillai Prabhakaran had led a legal set-up, they would have been put on the same pedestal as Bill Gates, Warren Buffet and Steve Jobs.

Transformation of Al-Qaeda

Like any business, terrorist organisations require three things: capital, labour and a brand or a mission.2 In other words, terrorists need financial capital, human capital and intellectual or knowledge capital to support their mission. How well all these are put to best use and managed determines the success or failure of an organisation. The ability of a terror group can be measured by how fast it adapts to changes in the external environment and internal changes. In a terror group, most internal changes are a direct result of changes in the external environment. One such group that has managed to change effectively in an ever-changing external environment is al-Qaeda, evolving in the following ways:

Like any business, terrorist organisations require three things: capital, labour and a brand or a mission.

- Maintaining a dynamic intra- and inter-organisational structure and network

- Evolving mission values

- Ensuring infusion of fresh blood globally

- Maintaining a diversified financial network

- Encouraging strategic innovations aided by technological advancement

Dynamic Intra- and Inter-Organisational Structure and Network

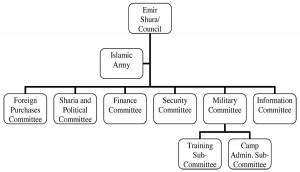

Contemporary terror organisations follow two types of organisational structures, hierarchical and network. Al-Qaeda started as an organisation with a commander-cadre structure with a vertical leadership structure that provides strategic direction and tactical support to its horizontal network of compartmentalised cells and associate organisations.3 After 9/11, much of its infrastructure has been obliterated. Some experts believe that al- Qaeda transformed from a hierarchical to a flat structure, or a network structure. Law enforcement efforts have forced al-Qaeda to transform itself into loose networks, which ultimately led to a virtual network.4

There are some paradoxical views to this such as the fact that a command-cadre structure suits the organisation’s goals more than a network-based structure and has kept al-Qaeda from collapsing in spite of it facing heavy odds.5 While a hierarchical set-up gives the central leadership better control over its operations and subjects, it is much more susceptible and prone to disruption. Since 2001, al-Qaeda has lost four heads of the Military Committee, four chiefs of the Special Operations Unit, and at least half a dozen of senior regional field commanders.6 Yet, it has always found replacements for these cadres and maintained the status quo as the most deadly terror group in the world.

After 9/11, al-Qaeda retained a hierarchical structure at its super structure level whereas it chose a flat network for its next level sub-structures. It also chose to decentralise its links with its affiliates and other groups. The hierarchical super structure allowed Bin Laden to ensure control over flow of information, resources and status. At the same time, virtual sub-structures ensured the resilience of the lower strata, which carry out operations. The very fact that it has been able to find replacements without compromising on the structural integrity and efficiency of its operations is ample testimony to the fact that the structural evolution of al-Qaeda has been successful at the super-structure level. Al Qaeda’s organisational structure is depicted in Figure below.

- Shura/Advisory Council: Osama bin Laden’s inner circle; director of the overall strategy of the organisation

- Sharia/Political Committee: Responsible for issuing fatwas

- Military Committee: Responsible for conceiving and planning operations, as well as managing training camps

- Finance Committee: Responsible for fundraising and concealment of assets

- Foreign Purchases Committee: Responsible for the acquisition of foreign arm and supplies

- Security Committee: Responsible for physical protection, intelligence and counter-intelligence

- Information Committee: In charge of propaganda

Since 2001, al-Qaeda has lost four heads of the Military Committee, four chiefs of the Special Operations Unit, and at least half a dozen of senior regional field commanders. Yet, it has always found replacements for these cadres and maintained the status quo…

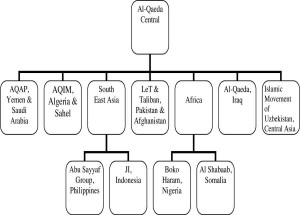

After 9/11, al-Qaeda’s centre, or core, weakened, but it overcame this lacuna by fully outsourcing terror globally through a network of affiliated organisations around the world. It has inspired affiliated groups with origins in the Middle East, east Africa, Asia and the caucuses to carry out attacks. Regional affiliates, like al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), al-Qaeda in Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), al-Qaeda in Iraq and the Moroccan Islamic Combatant Group (GICM), have been very active in the past decade. Other affiliate groups, like Jemaah Islamiyah (JI) in Indonesia, Lashkar-e- Taiba (LeT) in Pakistan and the Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG) in Philippines, are active in the Asian subcontinent. “These groups that hold declared or undeclared membership of World Islamic Front was formed in 1998 for waging a Jihad against the Jews and the Crusaders.”8 These groups have taken on the burden of al-Qaeda and conducted terror attacks at the rate of four attacks per year while a weakened al-Qaeda has mounted only one attack per year on an average.9 New groups, like Boko Haram10 and Al Shabaab, have joined ranks with al-Qaeda.11 By bringing more groups within its fold and widening its mission and objectives, al-Qaeda has made itself relevant to the current issues, thereby averting an identity and redundancy crisis.

Evolving Mission Values

All forms of entities face identity crises. Terrorists groups are no exception. An identity crisis comes as a result of patrons losing interest in the movement due to various reasons. Hence, changing needs and expectations are given paramount importance, as without them, the very purpose of a group’s existence would be lost. Handling expectations and managing and catering to changing and evolving needs, both internal and external, are an integral part of a successful organisation. Likewise, al-Qaeda’s customers are its members, patrons who donate, associates of like-minded groups, Islamists with radical intentions and sympathisers. After the end of the Cold War, for many radical Islamists, the theatre of interest shifted to domestic strife in countries like Sudan, countries in South East Asia, Kashmir and Kosovo.

Al-Qaeda shifted its focus from the Soviet Union in Afghanistan in the 1980s to overthrowing Americans from Saudi Arabia in 1998 and later expanded to fight the new world order, appealing to an extraordinary group of individuals and groups across the political spectrum.12 Al-Qaeda’s mission has changed and evolved over the years, encompassing new theatres of Islamic unrest worldwide. It has used the domestic conflicts in multiple countries, thereby broadened its mission and objectives. This has attracted existing as well as new patrons and potential recruits and brought them into their fold, which has ensured new recruitment fields, new avenues for finance and new theatres of operation. This has helped al-Qaeda sustain its relevance to other like-minded groups globally.

Al-Qaeda’s mission has changed and evolved over the years, encompassing new theatres of Islamic unrest worldwide.

Recruitment and Funding

People have always been al-Qaeda’s core strength at its sub-structure or operational levels. After 9/11, these levels only grew. The organisation was decentralised at its sub-structure levels. Operational commanders and cell leaders assumed greater authority and wielded decision-making powers previously unheard of in al-Qaeda.13 Greater autonomy, freedom and decision-making enabled the creation of overnight leaders. It will be a surprise to many that most of the jihadis are volunteers rather than recruits. Mr. Sageman, a terror expert, states that, “There is no recruitment, really. In my sample, I have found no case of a recruiter. They’re all volunteers.”14 As a result of its evolving mission, al-Qaeda started attracting new cadres from different parts of the world and belonging to diverse backgrounds.

Al-Qaeda had a very robust financial network prior to 9/11, including charities, donations from wealthy Saudi nationals and trade in commodities (weapons, drugs and precious gems) supported by both formal and informal systems of remittance like hawala.15 It relied on a combination of both legal and illegal sources of funding. After 9/11, as these networks were dismantled by the global war on terror, it chose new-generation fundraising techniques and methods like credit card frauds, funds derived from criminal proceeds and economic crimes.16 It also started raising funds through individual patrons.17 By evolving its mission into a broad-based one of fighting the new world order, it garnered new patrons, creating new sources of recruitment and funds.

Al-Qaeda’s financial relationship with its affiliates was such that most of the groups raised their own sources of funding while some, like JI in Indonesia, were partially funded by al-Qaeda.18 There were instances where reverse flow of funds were witnessed from the operational cells to the central command, indicating that operational cells have self-generating mechanisms and that al-Qaeda probably had a resource crunch.19 In spite of global efforts to stop the flow of funds to al-Qaeda, it has managed to ensure a steady flow of money. This shows that al-Qaeda has diversified its sources of funding. It has mitigated the risk by scattering its investments, raising funds through newer sources and developing its existing sources.

Strategic Innovations: Force Multipliers

Al-Qaeda has brought in innovative concepts and practices to fine-tune its operational and organisational capabilities. These innovations are the cornerstone of its success and ability to survive. Some arose at the strategic level while others arose at the tactical level. A few of them are listed as follows.

By forging alliances, it utilised the human, financial and intellectual potential of other groups.

Strategic Alliances and Mergers

As stated earlier, al-Qaeda forged close ties with many like-minded organisations across the globe. These relations increased their operational reach, effectiveness and efficiency by harnessing the expertise or strength of other groups.20 In business terms, these relations give access to new target markets, helping gain capabilities and share the financial risk. Al- Qaeda was able to operate in newer territories out of their bounds earlier. By forging alliances, it utilised the human, financial and intellectual potential of other groups. Similar to legal entities which enter into joint ventures with local partners to gain foothold in new markets, al-Qaeda started using its alliances to expand its reach. Al-Qaeda’s partnerships and alliances in various states are diagrammatically represented in Figure below.

Research and Development

Most terror groups have their own styles of conducting terror operations. Some groups might target hard targets, like government combatants and government installations, which are protected, while some might target soft targets, like civilians, who are not protected. Al-Qaeda’s own signature methods have been coordinated simultaneous multiple attacks against hard targets as well as soft ones. Terror operations like the 9/11 attacks and the Tanzanian Embassy bombings need meticulous planning and execution, which rests on knowledge already possessed with respect to proposed terror operations. Al-Qaeda has specialised in learning from its failed operations conducted earlier. The September 11, 2001, terror attack in the United States and the October 2000 USS Cole attack in Yemen were the most successful ones. Many are not aware that these terror attacks were actually preceded by failed terror attacks similar to the well-known ones.

Al-Qaeda has long recognised that it must engage the enemy on several fronts simultaneously and that its media strategy is both crucial and complementary to its operational activities in achieving its strategic objectives.

Operation Bojinka was the failed predecessor to the 9/11 attacks22 while a suicide attack similar to the successful USS Cole attack on a US naval ship failed as the boat sank because it was overladen.23 Al-Qaeda learned from its past mistakes and extracted the much needed knowledge in the form of learnings from its previous failures. It is a classic example of adaptive management, wherein al-Qaeda used its existing knowledge from its failed attacks, fine-tuned and cleared the obstacles by exploring an alternative method and conducted the attacks successfully later.

After 9/11, al-Qaeda, under Osama bin Laden, encouraged free flow of information from lower echelons to higher ones. This set the stage for new ideas emanating from lower-level cadres. This kind of liberal democratic information flow from employees in business aspects can be attributed to participative management, where employees are allowed to participate in the decision-making process facilitated by a vertical flow of information. These kinds of interactions have never been cited in other terror groups, most of which are highly tyrannical. Some experts have likened al-Qaeda to the Ford Foundation, where projects presented by researchers are evaluated and only some are funded while most are discarded.24 It has also encouraged new research and invested in new ideas. A chemical and biological weapons program called The Yoghurt Project, costing a meagre $4,000, was the brainchild of Ayman Al Zawahiri (the current leader of al-Qaeda) and can be cited as one of the instances where al-Qaeda shows an inclination towards investing in destructive research.25 Some experts have classified al-Qaeda as a multinational and its associate Islamist groups as its subsidiaries, with al-Qaeda providing venture capital.26 JI submitted a proposal to al-Qaeda to attack the Yushun Mass Rapid System in Singapore. The proposal was presented to Bin Laden and accepted in principle though it is still not clear why it was never carried out.27

By encouraging free vertical flow of information, which facilitates new ideas, and by closely monitoring earlier processes to fine-tune system lacunae, al-Qaeda has fostered evolution both structurally and organisationally. Essentially, it has created a team environment at the midmanagement level and below to protect its goal. This has also allowed the central leadership to support without participating but still have a commanding and motivating impact.

Propaganda and Public Relations

The media represents two-thirds of the battle. —Ayman Al Zawahiri

Al-Qaeda has long recognised that it must engage the enemy on several fronts simultaneously and that its media strategy is both crucial and complementary to its operational activities in achieving its strategic objectives.28 Violence as a product of ideology and capacity has been brought out well by al-Qaeda. It has used all forms of media and technology to disseminate its messages to the general public, which is its target segment. Most successful of them have been acts of violence, which by themselves are a very powerful marketing tool but with very negative connotations. It has a dedicated media committee, which handles the propaganda part (Fig. 1 above).

The growth trajectories of terror groups like al-Qaeda are a result of borrowing and implementing concepts from legal entities. It is now imperative for us to learn from these terror groups, who have customised and implemented these concepts to fine-tune their efficiency and activities.

The organisation has used a combination of marketing communications to project its messages to the outside world. It has integrated various tools and media to market its message to active customers (members, potential members and like-minded groups) and passive customers (general public), which form the core of its effective communications strategy. Al-Qaeda has been especially adept at manipulating television through the release of videos.29 In addition, virtually every incident conducted by the terrorist organisation is talked about on its website, targeting potentials for recruitment and spreading the message of bloodshed. Al-Qaeda has successfully aimed and achieved two major returns through its programs, one is “fear” and other is “support,” the latter helping to build equity while the former helping to build resilience through fear-driven deterrence.

Conclusion

The growth trajectories of terror groups like al-Qaeda are a result of borrowing and implementing concepts from legal entities. It is now imperative for us to learn from these terror groups, who have customised and implemented these concepts to fine-tune their efficiency and activities. These terrorists groups advertently and inadvertently are imparting lessons of terror to other terror groups and to the law enforcement agencies as well.

Terror groups like al-Qaeda have shown great adaptability, nimbleness and resilience in managing their organisations. On one hand, these aspects make them competitive. On the other hand, these make them as vulnerable as business entities in a competitive business environment. Law enforcement agencies can enlighten themselves on this vulnerability aspect by studying and understanding their evolution models, which may eventually bring about their downfall. Instead of fighting terror organisations with laws and guns, nation states need to study the strength of their flexible structures, which brings about efficiency, and frame policies. These efforts have to be focused to ensure more attrition in terror groups, which will steer human capital away from these groups, causing the groups to lose their financial capital and fall into recession.

The irony is that law enforcement efforts have proved to be counterproductive, forcing these groups to transform themselves into virtual networks and making it much harder to detect and disrupt them. It is imperative that any efforts to counter these be planned taking into account their constant and consistent evolution.

In the end, al-Qaeda has followed its objectives by evolving its goals, structure and functionality as the situation demanded and attempting to progress towards those goals. In the process, the organisation has often tasted success while failures have been far and few.

Notes and References

- The reason that al-Qaeda alone has been selected is because it is the only group that has survived a concerted, coordinated multinational campaign. This group has shown tremendous resilience and tenacity and maintains status quo as the deadliest group even after Osama’s death.

- J. Stern and A. Modi. “Producing Terror: Organisational Dynamics of Survival.” In Countering the Financing of Terrorism. Edited by J. Biersteker and E. Eckert. New York, NY: Routledge, 2008. p. 22.

- R. Gunaratna. Inside al Qaeda: Global Network of Terror. London: Hurst, 2002. p. 54.

- Op cit, n. 2, p. 29.

- R. Gunaratna and A. Oreg. (2010). “Al Qaeda’s Organizational Structure and Its Evolution.” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 33, no. 12, 2010. pp. 1043– 1078.

- Ibid., p. 1066.

- Government of the United States. “Overview of the Enemy, Staff Statement No. 15.” National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States, 2004. <http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/911/staff_statements/staff_statement_15.pdf>.

- Op cit, n. 3, p. 49

- Ibid., p. 49.

- D. Smith. “Africa’s Islamist Militants Co-ordinate Efforts in Threat to Continent’s Security.” 26 January 2012. <http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2012/jun/26/africa-islamist-militantscoordinating- threat>.

- J. Rollins. ”Al Qaeda and Affiliates: Historical Perspective, Global Presence, and Implications for U.S. Policy.” Government of the United States, Congressional Research Service, 25 January 2011. <http://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/ terror/R41070.pdf>.

- Op cit, n. 2, p. 33.

- Op cit, n. 7, p. 11.

- M. Sagemen. “Understanding Terror Networks.” E-Notes, Foreign Policy Research Institute, 2004. <http://www.fpri.org/>. Sageman conducted a survey on biographies of 400 terrorists belonging primarily to al-Qaeda.

- United States General Accounting Office. “U.S. Agencies Should Systematically Assess Terrorists’ Use of Alternative Financing Mechanisms.” Report to Congressional Requesters, November 2003. <http://www.gao.gov/assets/ 250/240616.pdf>.

- Financial Action Task Force. ”Terrorist Financing.” 29 February 2008. < h t t p : / / w w w . f a t f – g a f i . o r g / m e d i a / f a t f / d o c u m e n t s / r e p o r t s / FATF%20Terrorist%20Financing%20Typologies%20Report.pdf>.

- M. Levitt. “Al-Qaida’s Finances: Evidence of Organizational Decline?” CTC Sentinel 1, no. 5, 2008. < h t t p : / / w w w. w a s h i n g t o n i n s t i t u t e . o rg / u p l o a d s / D o c u m e n t s / o p e d s / 4807814218aed.pdf>.

- Z. Abuza. “Funding Terrorism in Southeast Asia: The Financial Network of Al Qaeda and Jemaah Islamiyah.” NBR Analysis 14, no. 5, 2003. <http:// www.nbr.org/publications/nbranalysis/pdf/vol14no5.pdf>.

- Op cit, n. 17.

- K. Cragin, P. Chalk, S. A. Daly and B. A. Jackson. “Sharing the Dragon’s Teeth, Terrorist Groups and the Exchange of New Technologies.” RAND Corporation, 2007. < h t t p : / / w w w. r a n d . o rg / c o n t e n t / d a m / r a n d / p u b s / m o n o g r a p h s / 2 0 0 7 / RAND_MG485.pdf>.

- The figure has been derived by the authors from multiple sources, such as the congressional research service and US government reports like the 9/11 staff statement, and supplemented with information derived from works of Rohan Gunaratna, Aviv Oreg and David Smith.

- Government of the United States. “The 9/11 Commission Report.” National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States, 2004. <http:/ /www.9-11commission.gov/report/911Report.pdf>. According to the 9/11 Commission Report, Operation Bojinka was originally planned and conceived by 9/11 mastermind Khalid Sheikh Mohammed in 1995, when he was not a member of al-Qaeda. It envisaged bombing of commercial airliners over the Pacific and flying a Cessna filled with explosives into the CIA headquarters, Langley. This attack was aborted as there was an accidental fire in the safe house in Philippines. This is the operation which gave al-Qaeda the idea of using aircraft as weapons.

- Ibid. According to the 9/11 Commission Report, Rahim Al Nashiri originally planned to attack USS The Sullivans in January 2000 using an explosives-laden boat. It failed as the overladen boat sank. The al-Qaeda learned from this failed attempt that the bomb needed to be a “shaped charge,” which would cause more damage per pound of explosive and allow the attackers to carry a lighter-weight, more effective bomb, which would not sink the boat.

- Op cit, n. 3, p. 68.

- A. Cullison. “Inside al Qaeda’s Hard Drive: Budget Squabbles, Baby Pictures, Office Rivalries—and the Path to 9/11.” 1 September 2004. <http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2004/09/inside-al-qaeda-s-hard-drive/ 303428/>.

- Op cit, n. 3, p. 69.

- Ministry of Home Affairs, the Government of Singapore. ”White Paper – the Jemaah Islamiyah Arrests and the Threat of Terrorism.” January 2003. <http://www.mha.gov.sg/publication_details.aspx?pageid=35&cid=354>.

- A. Gendron. “Al Qaeda: Propaganda and Media Strategy.” Trends in Terrorism Series 2007, no. 2, 2007. <http://www.itac.gc.ca/pblctns/tc_prsnts/ 2007-2-eng.pdf>.

- Op cit, n. 7