“Where the mind is without fear and the head is held high …

Into that heaven of freedom, my father, let my country awake.” —Tagore

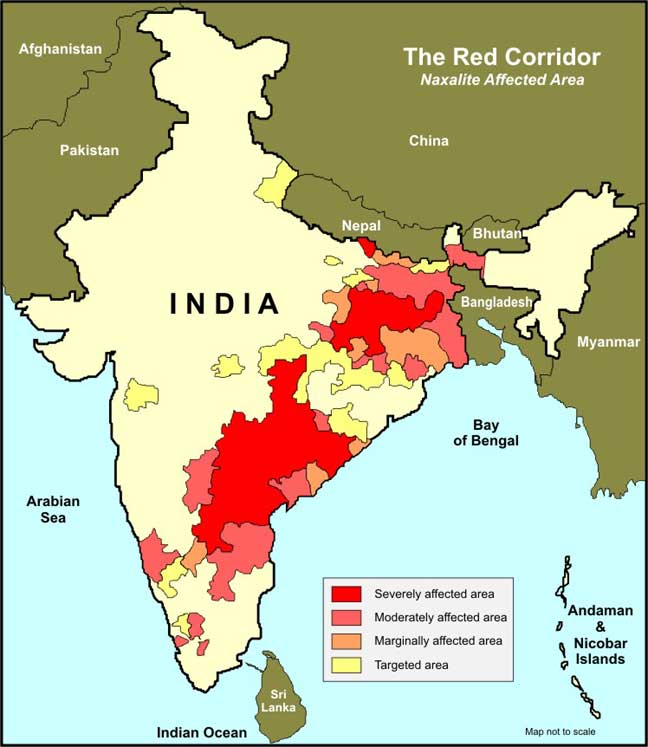

India is a millennium old civilisation of diverse peoples, hosting one sixth of the entire humanity within its borders; twenty seven percent of them live below the ‘poverty line’. There is a huge socio-economic disparity that gives rise to feelings of deprivation and desperation among the mass of destitute ‘have-nots’. A feeling of neglect at the hands of the state has thus driven a large section of the young population to revolt against the system. Today, one in every sixth Indian lives under the shadow of insurgency. Among the insurgent groups, the Naxals or the Maoists have a sway of their influence over approximately one fourth of the 600 plus districts in India.

…when an unrest threatens to assume proportions of an armed insurrection that could threaten the very framework of the state, it is time to institute comprehensive and well thought out control mechanisms. No doubt, the Maoist rebellion had reached that stage at least a decade back.

With the coming of the ‘Information Age’ and spread of awareness, and whereas nations and societies are constantly creating wealth, Maoism or the Left Wing Extremism (LWE) manifests as an expression of the rising aspirations of the deprived lot for a life of dignity and self respect. The pattern and intensity of violence perpetuated by the Maoists is therefore an indicator of emerging challenges to internal security and economic stability of the nation. Needless to mention that the potentially destabilising situation, as brought about by the spread of Maoism, merits immediate attention of the governing establishment because the goal of economic growth can be achieved only in a peaceful environment.

India is developing – and fast. Following the eternal law of societal progression, development is germinating in isolated pockets of geographic locations, vocational sectors and classes of people. By the natural law of diffusion, steady spread of that progress to cover larger and larger parts of the country is but a foregone conclusion. However, this can happen only if the authority of the state prevails and the law of the land is operative unhindered from rebellious groups dictating their violent agenda. Controlling the Maoist rebellion is therefore a priority concern of the state; the cycle of disparity-turmoil-more disparity-more turmoil> has to be broken.

A major lacunae in addressing the Maoist problem is caused by a blurred vision of the true picture – motivations conditioned by expectations of promoting short term self interests. This disorientation poses hindrances to charting of effective processes by which the rebellion may to be tackled. Strangely, even after two decades, there are policy makers at the State and Centre levels who view the rise of insurgency as baseless acts of Left Wing Extremism (LWE) while some are still of the opinion that it is just a law-and-order problem. There is a third school of opinion that sees it as the “single biggest internal security challenge ever faced by the country”. Even in the parliament, there are different perceptions; some consider the officially conservative statistics on the spread of Maoist menace – 14000 villages out of 6,50,000 and 300 police stations out of 14000 being affected – as not really extraordinary, while others find it alarming enough to demand imposition of emergency. The path to a solution thus remains in confusion while the professors of ‘rosy picture’ versus ‘doomsday’ criers argue endlessly. Self interest still remains the primary consideration in supporting or opposing the rebellion. It does not seem to prick the political conscience that the Maoists run an elaborate network of parallel, grossly unconstitutional governance across vast stretches of the country.

A Near-Continuum of Rebellion

Rebellion of the masses in India’s hinterland areas against political and economic atrocities of the ruling establishments is not a new phenomenon. In many cases, groups of the tormented taking to hills and jungles to wage various shades of armed insurrection has been more or less a regular feature during the past three centuries. Indeed, there has been a succession of violent uprisings engulfing one part or the other of the Indian landmass. Thus the later part of the Eighteenth Century saw the demobilised soldiers of defeated remnants of the Mughal Empire as well as the Maratha rulers joining hands with exploited peasants and tribals to revolt against forced appropriations by their debauched rulers and their European mentors; though in keeping with the practice in vogue in those days, these unruly rebels did not spare the other equally oppressed countrymen from robbery and loot. Sanyasin rebellion in Bihar-Bengal, the uprisings of the Pindari and the Baghi marauders in the Northern Plains and that of the many groups which formed part of what was referred to as the ‘Southern Peninsula Confederacy’ and the ‘Paharia Sardars’ are some notable examples of such conflicts. Then there were a succession of uprisings during the entire course of the Nineteenth Century in which the tribes of Chhotanagpur Plateau – Bhil, Gond, Ho, Oraon, Kol, Santhal and Munda – as well as the cultivators of indigo and artisans of the cottage industry from the plains put the Angrej-Raja-Bania (British-Prince-Merchant) axis of exploiters to severe test.

…it was sometime in the Year 2008 that certain concrete steps were initiated by the governments to control the runaway situation. By then hundreds of police men had been massacred…

The rebellious saga continued in the Twentieth Century too in the form of the Bastar and Tana Bhagat uprisings in Chotanagpur, the Gond rebellion in Andhra, the Naga, Lushai and Abor insurgencies in the North-East, and the Telengana and Naxal rebellion. Of course, the distinguishing lines between ‘uprising,’ ‘banditry’ and ‘terrorism’ has ever remained blurred, as it is also in the case of the present Maoist rebellion. Many of these insurrections needed the government’s full armed might, over time, to bring under control. Conversely, there were occasions when many uprisings could be nipped in the bud by effective steps adopted by the government to ameliorate the causes, with only limited dependence on armed action.

It would therefore not be out of place to conclude that violent upheavals against systemic injustice, mostly real and some perceived, some inflicted due to systemic constraints and some contrived by powerful exploiters, has been but an eternal process of societal churnings. It is also clear that the signs of impending upheavals require to be addressed with alacrity, and that under-reaction on the part of the government of the day to let the conflict gather momentum is as self-defeating as any over-reaction to bring it to an abrupt suppression by force could be. Therefore, when an unrest threatens to assume proportions of an armed insurrection that could threaten the very framework of the state, it is time to institute comprehensive and well thought out control mechanisms. No doubt, the Maoist rebellion had reached that stage at least a decade back.

While out-break of armed rebellion among the masses against any oppressive oligarchy – indigenous or foreign – may be understandable, emergence of a situation such as the Maoist insurgency in a socialist democracy can not, by any stretch of leniency, be justifiable. It would therefore be natural to be dismayed at the gross ineffectiveness of the State governments in allowing the Maoist rebellion to grow over two long decades, just in order to whet their short-sighted political conveniences. Similarly, not bringing itself to respond to the growth of Maoist violence from the time this rebellion was known to be going the way of assuming menacing proportions, under the shelter of an ambiguous interpretation of constitutional federalism, was an inexcusable failure on the part of the Central Government. That the cost of such blunders are being borne by the people – in terms of death, backwardness and poverty – and so it would be for a long time to come, is a disturbing thought.

This brings into the focus some questions regarding the brand of democracy that gets to be practised in India.

Whither Democratic Pitfalls?

Even when the Maoist insurgency was at last officially recognised as the ‘gravest threat’ to the nation’s internal security, hardly any concrete measures to focus on dealing with the insurgency seems to have been taken with due earnestness. Apparently, every measure – strengthening the police forces, commencement of development schemes and passage of benign legislations – had to first conform to the political interests of the party in power and their committed vote-banks, then it had to pass the muster of being in conformity to the inter-departmental and inter-cadre pecking order in the government establishment, before protection of national interests could be looked at! There could be no more blatant abuse of a democratic system by its very guardians – the scope of democratic consensus can not extend to group-aggrandisement at the cost of long term national good, nor may the parameters of national good be open to partisan interpretations.

Factually, spread of the Maoist rebellion has not generated such strong emotions at the national level as it does in the case of Kashmir or Nagaland.

Elected guardians having failed, finally it was the subscribers of the same democratic governance, the common citizen, who by their nation-wide indignation prodded the State and the Central governments to take serious note of the Maoist mayhem. Finally, it was sometime in the Year 2008 that certain concrete steps were initiated by the governments to control the runaway situation. By then hundreds of police men had been massacred, thousands of villagers had been decapitated, millions of people in Central India had been consigned to a life of fear and extortion, and a parallel state had been functioning within the bosom of Mother India with impunity. The wisdom of undertaking timely preparations to handle an impending disaster having bypassed the policy makers earlier, deliberate efforts are being made since then to recover a situation long gone out of hand. Even then, these steps are incremental and have long gestation period – and therefore, limited in effect. The systemic maladies being deep rooted, the state’s capability to manage the situation has since improved but only marginally. It would take years of effort to control the menace that was allowed to grow over a period of nearly two decades. And that brings into open certain self-deceiving notions that go around in discussions all over the country.

Firstly, the Central Government’s announcement identifying the Maoist insurgency as the ‘biggest threat to the nation’ may not be justified. The rebels after all, in their stated position, demand only that what is guaranteed to the citizens under the constitutional provisions, nothing more – even if they must be brought to the book on account of their objective, in violation of the constitution, to change the system of governance by the force of arms. Indeed, there is a running debate on whether the Maoists are anti-nationals, or terrorists, or just revolutionaries jostling for the advent of social justice. Factually, spread of the Maoist rebellion has not generated such strong emotions at the national level as it does in the case of Kashmir or Nagaland. Besides, there are arguably other instances more sinister in nature confronting the nation: spread of the fanatic agents of terror, facilitation of demographic invasion and aggression emanating from the nuclear neighbourhood for example, which must compete for the description of ‘biggest threat’. In any case, if the Maoist insurgency was indeed the biggest national threat, then the measures adopted – or rather not adopted – by the government to deal with that threat, before and after it manifested, must qualify for condemnation.

Secondly, the nation’s policy makers need to ponder as to why do people having no wish to secede, have to choose to arm themselves with bows, spears, obsolete weapons and hide in jungles to defend their everyday aspirations, what forces the traditionally accommodative and peaceful children of Mother India to take up arms against their own state? Why has the independent, socialist and democratic India has landed up creating two categories of citizens – a miniscule minority lolling in opulence and an overwhelming majority surviving in utter misery? How will this disparity be ended when the majority of the power-wielders are themselves the beneficiaries of this injustice? How would protective legislations and enforcement of rules, as indeed even the allocation of public funds, be tailored to bring relief to the distressed population when these impinge upon the interests of powerful vested interests who dictate the governance? Why is the Maoist insurgency not active in larger regions which are equally poverty ridden and undeveloped, or in other words, what is the stronger call to rebel: disparity or poverty? How will India cope with the impending ‘Youth Bulge’ of cyclonic proportions, how will the young Indians be employed meaningfully to prevent them from forming dangerous cartels? How far true is the insinuation that in independent India, the reach and effectiveness of governance has stagnated, even retarded, in relative terms of population, their needs and the public services, as compared to the British rule – and that is the void that the Maoists are attempting to fill?

Lastly, granted that there were compulsions upon the Central as well as the State governments in dealing with the rise of Maoist insurgency in the ham-handed manner as they did. However, to view the insurgency as merely a law-and-order issue and then leave it for the affected States to deal with as they deemed beneficial, is no doubt a weak policy. Even giving the due consideration to India’s federal structure, there are two questions which need to be settled: one, at what stage an ostensibly law-and-order problem grows into a national internal security threat, and two, which institution, segregated from political equations, may be competent to decide if that stage has been reached at a point of time.

…to view the insurgency as merely a law-and-order issue and then leave it for the affected States to deal with as they deemed beneficial, is no doubt a weak policy.

Political thinkers are right when they aver that the Maoist rebellion is but a direct fallout of democratisation of governance and politicisation of interest groups. In other words, the rebellion is an extreme form of expression of dissent and demand that is propagated under the democratic advantages enjoyed by the weaker sections – advantages which give voice to the voiceless and encourage them to demand participation in governance. Therefore, in the overall context, Indian polity has to take serious note of the paradox that while at one end, people’s alienation with the government’s overlook of their fundamental concerns can not be suppressed by force, at the other end, the state is woefully short of resources that could ameliorate in one sweep, all the causes of people’s agitation. Further, there is a grave danger to the Indian nationhood if democracy becomes inter alia the rule of majority votes rather than the rule of law and fosters a system in which injury to one section of the people is endorsed to preserve the interests of a another section of beneficiaries of that system. In other words, the government’s challenge is to find means reasonable to protect the interests of the plateau-land tribes even while harnessing natural produce for economic development, and similarly, uplift the deprived sections among the plainsmen without imposing any major upset upon the better-off lot.

Concluding Remarks

In the end, it may be in order to mention certain theological impressions that appear in dealing with the subject of Maoist rebellion.

One, the Maoist revolution is driven by an urge to decimate ‘class enemies’ who are identified as the benefactors of ‘home grown imperialism,’ feudalism and ‘comprador bureaucratic capitalism’. The revolutionaries aim to do so by the means of ‘armed aggression,’ ‘protracted people’s war’ and finally, ‘armed seizure of state-power’. According to them, armed aggression is ‘not negotiable’; that is, any solution that may be found by other peaceful means will not do. This is a strangely diabolic affliction with blood-letting, and indeed, out of tune with the times. Apparently, the Maoist’s solidarity with the people’s difficulties, women’s cause, support to separatists and movement against class and caste system are but the tools to justify and propagate that affliction with armed aggression. In contrast, there are many among them who are inclined just to pay lip service to the party ideals, their sole purpose being to continue to reap the rewards of being revolutionaries, no more. Then there are many break-away groups, besides the factions within, who differ with the mode, manner and methods adopted by the Maoist leadership. These may be weaned away to isolate the fanatic Maoists.

…there are many break-away groups, besides the factions within, who differ with the mode, manner and methods adopted by the Maoist leadership. These may be weaned away to isolate the fanatic Maoists.

Two, the Maoists seem to have moved away from their traditional base constituency of the peasant class, to connect with rich landholders, creamy sections among the backward communities and the business community. In their contemporary version, the Maoist revolutionaries seem to have built up a nexus of common cause with the better-off classes. This may be a tactical understanding with the realisation that while the armed struggle may highlight the people’s difficulties, it can not find solutions to these – that endeavour has to bank upon the wielders of money power. As a result of this remarkable revision of communist ideology, its traditional support-base of working and peasant class may not be alive any more. Recourse to intelligence-based operations with participation of the masses to weaken the rebellion therefore may pay good dividends in countering the Maoist insurgency.

Three, with the leadership of the insurgency so broad-based – like the Al Qaeda – the rebellion may not be liable to be contained in just few strokes – it would need regular and steady conduct of counter operations over a long period to control. The state may therefore girdle up for a long grind.

Four, the state may need to take cognisance of the fact that there is a widespread perception that in many ways, the coverage of governance across the country-side may have retracted when compared to the days of the British Rule. This is a serious indictment of an independent India that needs urgent redress.

Five, the Maoist rebellion can not be controlled unless alongside the other measures, the process of criminal investigation and prosecution is restituted and effective judicial system is active.

…in a long confrontation between a flaw prone democratic system and communist revolution, people’s perception would play a crucial role, particularly so in the information age.

Six, looking at the rural youth of today, it becomes clear that the energy of the fast growing young population needs to be kept productively engaged for them to be kept away from becoming mobsters. The approaching ‘youth bulge’ is therefore a fearsome prospect, as much as it may be as an asset to the nation. The society has very limited time to find ways to deal with this situation.

Lastly, in a long confrontation between a flaw prone democratic system and communist revolution, people’s perception would play a crucial role, particularly so in the information age. So far, the Maoists, aided by their attractive – and assertive – propaganda that is well substantiated by the blatantly callous attitude of the governing class, has scored over the government. To turn around that negative perception, the government has to first come clean of its policies that agonies the voiceless people and then bring the facts to the notice at the grass-roots level.

Maoist rebellion is a topic of extensive dimensions. Therefore, the focus in this book has been confined to what comes out from visitations and interactions at the ground level and sharing the impressions gained with the community at large. Obviously, there would be differences of perceptions and opinions, may be even certain facts, but that may be set aside in favour of understanding of the Maoist rebellion from another angle. If these inputs help in the complex call that the policy makers face in negotiating through the problem, the purpose would be met.