Ranked fourth, India has a strong talent pool in science, technology and research, as well as some of the lowest labour rates in the world. Its concerns include the country’s regulatory environment, high interest rates, and healthcare system, as well as under-developed physical infrastructure. The country has a goal of moving its manufacturing share from 16 per cent of GDP to 25 per cent by 2022. Now the same is propelled by an aggressive policy for ‘Make In India’. The future outlook seems bright provided India can seize the opportunity.

What is the foreign ownership with which we can get the trinity of technology, capital and manufacturing? Can we kill all three birds at the same time to make India a Defence Manufacturing hub? With time, the context changes forcing change in strategy. In the past, India banked on the Licensed Production route. We kept building the same thing that we got from abroad. We failed to build the next upgrades on our own. We failed to migrate to the higher part of the value chain. We have been changing our recommendations on Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) from 26 to 49 per cent, from 51 per cent to 74 per cent and so on, without having achieved the desired results. Thus, we have to revisit our conclusion and determine whether an incorrect diagnosis has been made.

FDI has changed the consumer goods industry in many countries, including China. But, when we talk about defence beyond the boundaries of the parent nation, there is concrete evidence to substantiate that. Which country does not want its jobs not to be protected? When it creates place for FDI, it loses on the count of job creation in the parent country. The sacrifices done to overcome some of the structural market barriers, maybe Entry Barriers or it may be to reap the best benefit of factor inputs in the destination nation so that the parent nation earns more bottom line. We have to find cogent and coherent reasons why India still struggles to make its military industrial complex self-reliant and sustainable.

Saudi Arabia and UAE imported more weapons than all of Western Europe…

Correlation between FDI and Technology Independence

“The Biggest Arms Importer Is India – No More”. As per the IHS Global Defence Trade Report 2014, Saudi Arabia replaced India as the largest importer of defence equipment worldwide and took the top spot as the number one trading partner for the US. Saudi Arabia surpassed India to become the largest defence market for the US that supplied one-third of all exports and was the main beneficiary of growth. Saudi Arabia and UAE imported more weapons than all of Western Europe.

Saudi Arabia, Indonesia, Sweden and Nigeria are the UK’s top trading partners. One out of every seven dollars spent on defence imports will be spent by Saudi Arabia (IHS, 2015). The selling proposition for ‘Make in India’ for defence for high amounts of acquisition may not be valid. The same may not hold good after five to ten years. Thus, it is time to set things right, as building of national capabilities cannot be left to assumption of higher FDI and consequent development of indigenous capabilities through technology.

Overwhelming evidence is available that FDI does not necessarily and automatically lead to transfer of advanced technologies. A study by academicians from the University of Oxford concluded that entry of FDI indeed leads to spillover of technologies to the local economy but that such spillovers are not automatic. This beneficial impact of FDI, however, is limited to ancillary activities. Specific policies are required for such beneficial effect to happen. A study by the United Nations concludes that most Transfers of Technology from MNCs occur within higher-income developing countries.

A nation can take its procurement decision but the FDI decision remains with the MNC. Whether FDI brings technology or not depends partly on the State Control on exports of such technology. Ultimately what matters, is how competitive and attractive is the domestic sector in the domain of technology. Greater the capability, higher is the possibility to absorb advanced technology.

The Indian industry is facing a serious problem with regard to availability of labour…

Ease of Doing Business in India

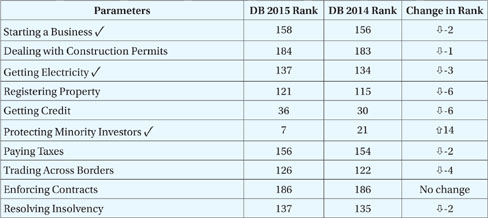

The World Bank has come out with “Doing Business 2015” data for India out of 189 economies. Since there are no specific studies on defence manufacturing, the same will serve us a benchmark. No nation in the world, which is weak in manufacturing, has emerged as a strong player in military armaments. The only improvement in 2015, over 2014 Rank is in the protecting minority investors. Thus, the policy changes due to ‘Make in India’ Campaign will take some time before making an impact on ground realities.

The comparative data of 2015 vis-a-vis 2014 for ease of doing business looks like this:

=Doing Business(DB) reform making it easier to do business. =Change making it more difficult to do business. Click here to see all reforms made by India.

Manufacturing Competitiveness

The 2013 Global Manufacturing Competitiveness Index by Deloitte (Deloitte, 2013) once again ranked China as the most competitive manufacturing nation in the world both today and five years from now. Germany and the United States are within the top three competitive manufacturing nations. What is USP of each of the countries? What makes them competitive? What is India’s USP?

Table 1: Global CEO Survey: 2013 Country manufacturing competitiveness index rankings

Executives believe China leads overall and emerging markets will become more competitive in the near future

It is important to know their national strategy that makes them lead players in manufacturing. In spite of its economic slowdown, China continues to maintain its rank as the most competitive manufacturing nation. Reasons cited are the advantages of its labour and materials cost, strong government spending in manufacturing and innovation and an established supplier network.

Ranking highest in talent-driven innovation, Germany continues to make impressive gains since 2010. There is a renewed focus on manufacturing, and manufacturing exports nearly tripled between 2000 and 2011. The country is focusing on new technologies and a highly skilled workforce. It is dominating the field of “mechatronics”, a multi-disciplinary field of science and engineering merging mechanics, electronics, control theory and computer science.

Ranking third, USA’s strength lies in its appeal as a manufacturing destination, core competency for talent-driven innovation, physical infrastructure, established supplier network and a strong legal and regulatory system. An overall sense of uncertainty that plagues the US regulatory system is seen as a significant disadvantage.

Only ten per cent of the MBA graduates and 17 per cent of engineering graduates in the country are employable…

Ranked fifth, South Korea’s strength based on its competitive cost structure and quality products. Its favourable industrial policies and highly educated and skilled workforce are definite advantages. Its complex policy and regulatory environment is viewed as a negative point.

Ranked fourth, India has a strong talent pool in science, technology and research, as well as some of the lowest labour rates in the world. Its concerns include the country’s regulatory environment, high interest rates, and healthcare system, as well as under-developed physical infrastructure. The country has a goal of moving its manufacturing share from 16 per cent of GDP to 25 per cent by 2022. Now the same is propelled by an aggressive policy for ‘Make In India’. The future outlook seems bright provided India can seize the opportunity.

The report found that access to talented workers is the top indicator of a country’s competitiveness – followed by a country’s trade, financial and tax system, and then the cost of labour and materials. Enhancing and growing an effective talent base remains core to competitiveness among the traditional manufacturing leaders – and increasingly among emerging market challengers as well. How good is India in these respects? How are the factors of production faring well for India?

The Labour Factor

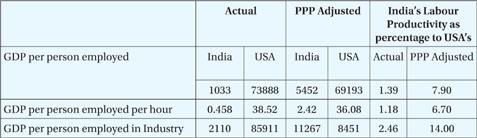

The table given below compares India’s performance in Productivity – Wage Relation with that of the USA, the world economic leader with the highest levels of labour productivity. For this purpose, the national output has been measured in terms of market values after adjusting for variations in Purchasing Power Parity (PPP).

Labour productivity levels in India and USA in 2000 (US $)

India’s labour productivity is distressingly low, the GDP per person employed being as low as 1.39 per cent/7.90 per cent (Actual/PPP) of that in USA. GDP per person hour employed is at 2.46 per cent/14.00 per cent (PPP adjusted) as compared to the USA. Although data may be outdated, not much has changed in the Indian landscape. High pay and low productivity makes Indian Public Sector employees one of the highest paid employees in the world. A recent study is quoted by Deloitte which bring out productivity in 2013.

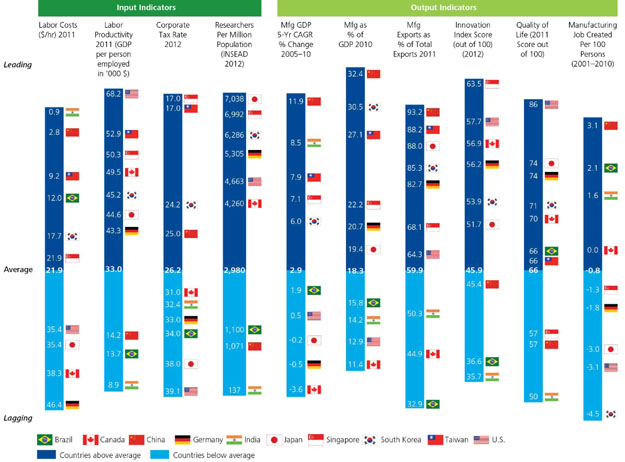

The graph shows that India’s labour cost although less (India, 0.9, China 2.8, USA 35.4, Germany 46.4), productivity at 8.9 (USA 68.2, Singapore 45.2, Germany 43.3, China 14.2, Brazil 13.7) is the lowest among comparative countries. Thus, low labour cost means little without productivity. The labour issue gets complicated with Unionism in the organised sector. In recent past, at Hyundai Motors India, subsidiary of the South Korean automaker, workers went on an 18-day strike to demand recognition of the employees’ union. The company has debated moving the Tamil Nadu-based plant to Europe (Most of the production is for export).

Supplemental data analysis: Competitiveness driven differently among most competitive nations. 2013 GMCI top 10 country comparisons of key country manufacturing related macroeconomic indicators (Source: Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited analysis)

At tyre maker MRF, the Arakkonam (Tamil Nadu) unit was closed almost a month due to rival unions clamouring for recognition in October 2010. Workers at auto factories attacked supervisors and started a fire that killed a company official and injured 100 managers including two Japanese expatriates. The violent mob also injured nine policemen. The company’s General Manager of Human Resources had both his arms and legs broken by his attackers, unable to leave the building that was set ablaze, and was charred to death. Operation was at less than ten per cent of its capacity at a loss of rupees one billion a day.

On December 17, 2010, at Honda Motors and Scooter India, a security personnel at the Honda factory misbehaved with a temporary worker. In response, temporary workers – not represented by the union- went on a wildcat strike, which brought production to a halt. The strike lasted for about 24 hours until the management intervened. The production loss is estimated to be Rs 7 crore (Ghosh, 2013).

India has to choose its area of specialisation in which it must demonstrate the product leadership..

Although statistically, there are fewer strikes and fewer losses of man-days due to strikes, the reason is that companies are expanding hiring on contract, as opposed to permanent workers. The contract system gives companies greater autonomy in choosing when to lay off workers in times of a slump, as the Industrial Disputes Act requires permission of the Government for lay-offs if the unit deploys more than 100 workers. Moreover, the same has been planned move by the management to prevent “unionisation”. There is a small core of permanent workers, but a substantial number of workers are now hired on contract. Maruti for instance, has 85 per cent contract labour. According to news reports, the proportion of contractual labour in Nokia is 50 per cent, and that in Ford is 75 per cent.

Temporary workers are in a permanent state of alienation with their wages being a fraction of permanent workers. Their commitment to the company for innovation is questionable. Thus, the inefficiency of the permanent workforce is transferred to the temporary workforce. Moreover, as the data shows, India’s innovation score is at bottom compared to others.

A white paper, “People Power: Human Capital Drives Manufacturing Competitiveness by Tooling U-SME (Tooling U-SME, 2015)” brings out how a well-trained workforce is a competitive advantage, allows companies to drive innovation, customer satisfaction, productivity and growth.

FDI has changed the consumer goods industry in many countries, including China…

A culture of learning including a structured workforce development programme can lead to engaged and loyal employees, satisfied stakeholders and economic growth. The report says even if two companies have the same technology, equipment, processes and materials that does not mean they have the same success. Companies that invest in developing their people are seeing the strongest results related to increased profits and productivity and reduced downtime and waste. Although we may boast of young population, the skill deficit in India is alarming. As per a Price Waterhouse Coopers (PWC) report in 2014, 63 per cent of the CEOs across the world surveyed for the report said that availability of key skills is the biggest business threat to their organisation’s growth.

A FICCI Survey on Labour/Skill Shortage for Industry (FICCI, 2015) brings out that Indian industry is facing a serious problem with regard to availability of labour. Several companies have reported that their workers have started demanding higher wages and that companies are already beginning to face difficulties in terms of meeting confirmed orders on account of shortage of workers. About 89 per cent of the respondents said that they have been unable to fully meet the potential demand for their products in the market due to labour shortage. When asked to comment on the extent of potential loss due to shortage of labour, nearly two thirds of the participating firms said that their potential losses are to the extent of more than ten per cent of their demand.

As per CII’s India Skills Report, 2014, India has 60 per cent of its total population available for working and contributing towards GDP but out of the total pool only 25 per cent is capable of being used by the market. If the research findings are to be believed, there would be a demand-supply gap of 82 to 86 per cent in the core professions. Only ten per cent of the MBA graduates and 17 per cent of engineering graduates in the country are employable.

No nation in the world, which is weak in manufacturing, has emerged as a strong player in military armaments…

A major reason for this is the classroom teaching orientation of most Indian universities, which themselves are far behind their global peers (as per the Times Higher Education World University Rankings 2013-2014, not a single Indian university figures in the top 200). This scarcity of skilled talent makes it impossible for the Talent Supply Chain to operate effectively and is an issue which if not taken care of immediately will become uncontrollable (CII, 2014).

Capital Factor

An EY (formerly Ernst & Young) survey (EY, 2014) has found that the average cost of equity capital in India is around 15 per cent. It has increased over last the three to four years and higher than most of the developed nations. The survey highlighted the fact that the average difference in the cost of capital for investment in India is 3.6 per cent in comparison to developed countries.

Another measure of efficiency and productivity of capital investments in the economy is the Incremental Capital Output Ratio (ICOR). A higher ICOR is an indicator of inefficiency – a higher level of investment is needed to produce one extra unit of GDP. ICOR is calculated as the ratio of fixed investments to incremental GDP (at market prices). Compared to an ICOR of 4.1 for the 10th Plan, the 11th Plan achieved an ICOR of 4.5, indicating erosion in resource use efficiency (PIB, 2013). According to the new GDP series, India’s ICOR fell from 6.6 in fiscal 2013 to 4.3 in fiscal 2015. This means that over the years investments did become more productive. Even in the old series (with 2004-2005 base), ICOR was 7.5 in fiscal 2013 and fell to 6.8 in fiscal 2014. Although, the ICOR is improving, the same is not promising.

ICOR can be lowered through a mature and better infrastructure. This requires huge investment. A modern port with fast turnaround times requires Rs 6,000 crore minimum outlay. In India, ICOR would continue to be high so long as the economy does not develop to be on a par with a developed country vis-a-vis infrastructure and manufacturing industry. The large ICOR is largely attributable to supply constraints such as power-coal imbalance and inordinate project delays. There is no immediate magic wand to bring it down.

A culture of learning including a structured workforce development program can lead to engaged and loyal employees…

Land Factor

Production of any kind of goods and services requires land. However, delay in land acquisition, protests and resistance on the part of the displaced have become central tailbacks for investments in the infrastructure sector. Whether it is Singur or Gopalpur, they stand as stark reminder of the risk and uncertainly of land acquisition. Environmental clearance adds to delays. Cost overruns and risks in infrastructure projects are intrinsically linked to land acquisition. The issue of displacement of inhabitants and the focus on environmental degradation activists in the country has become an opportunity for politicians to create an image of themselves in front of innocent citizens.

Although the new Land Acquisition Act removes many constraints, it makes the cost of land higher. The industry will wait and watch how things are affected on ground. Businesses will need to continue relocating affected populations, compensating affected individuals with two times the land’s market rate for urban property and four times the rate for rural property. These relocation costs are as prohibitive as the complicated social impact and public approval process.

Recommendations

If the country has to make a success of the “Make in India” objective, these serious drawbacks in the “human capital” domain will need to be addressed. The proportion of PhDs in the R&D or manufacturing organisations is low. However, to overcome the quality constraints, organisations such as ISRO and Atomic Energy Commission have devised their own methods. ISRO, for instance, runs a dedicated university, the Indian Institute of Space Science and Technology (IIST) that taps talent at a very early age and provides graduate, post-graduate and doctoral programmes in the areas of space science and technology. There is no such technical institution available for the defence industry.

Estimates suggest that almost 50 per cent of the workforce in this R&D sector is constituted by engineers and management graduates. Countries like France have developed highly regarded specialist schools like Institut Superier de l’Aeronautique et de l’Espace (ISAE) and Ecole Nationale de l’Aviation Civile (ENAC) in Toulouse and Ecole Nationale Superieure de Mecnique et d’Aerotechnique (ENSMA) in Poitiers to train engineers for this field. As the French industry grew, substantial investments were made in the form of professional federations such as Groupement des Industries Francaises Aeronautiques et Spatiales (GIFAS) to promote the interests of this sector. With a pool of 134,000 specialist employees, the French Aerospace and Defence industry today is clearly a European leader (KPMG, 2010). Thus, there is a need to promote National Technological University by converting few institutions such as an established IIT with few Centres of Excellence, DRDO/CSIR laboratories rather than starting de novo.

Countries like France have developed highly regarded specialist schools…

Instead of focusing on the entire gamut of defence production, India has to choose its area of specialisation in which it must demonstrate the product leadership. Let us the take case of positioning in the manufacturing landscape. The US emphasizes on next generation materials (and novel materials engineering) for manufacturing. Japan focuses on the implications of demographic change and they prioritizes research on new production technologies for an ageing workforce with a focus on quality and reliability. Germany puts its efforts related to manufacturing processes and capital machinery that protect products from piracy. Brazil places emphasis on bio-fuel and petrochemical technologies. Resources cannot be spread thin. Thus, it is better to focus resources on few core areas where such concentration will lead to better result in a defined time span. For example, India can make the Hyper Velocity Electromagnetic Gun, Next Generation Battlefield Management Systems and Stealth Technology based on systematic study of comparative advantages.

Conclusion

A national ecosystem must be created so that capability enhancement, infrastructure development and technologies development happens though removing supply side constraints such as skilled manpower, cheaper capital and enhanced efficiency. The structural bottleneck of the industry must be removed by making it easier to do in business through a push by reducing the Red Tape, improving infrastructure and availability of cheap power.

Considering the limited time horizon in which this must be achieved in line with national aspirations, this must be undertaken as a national mission with industry, academia and R&D coming together and government setting the direction of reforms, sitting in the driver’s seat. This is possible with a National Technological University being set by converting one of the established IIT and like-minded complementary institutions with international collaboration. The collaboration is beyond the capability of any single organ and institution. The state has to play a lead role with the user driving the innovations.

A defence national manufacturing investment zone with academia industry hand in hand would ensure steady supply of the skilled manpower…

This National Technological University would create a Silicon Valley around it with generous seed and venture capital funding. The Silicon Valley is the story of a number of pioneers who were able to produce an environment that stimulated the emergence of entrepreneurial talent. The density of the starts up makes it entrepreneurial. The cluster allows seamless flow of people, ideas and capital making it a hotbed of innovation. Such a defence national manufacturing investment zone with academia industry hand-in-hand would promote collective learning and ensure steady supply of the skilled manpower. Such cluster’s dense social networks and open labour markets would encourage experimentation and entrepreneurship. All the aspiring and leading players should have their bases in this defence Special Economic Zone (SEZ). While companies in this SEZ can compete intensely, at the same time, they can learn from one another about changing markets and technologies through informal communication and collaborative policies. Time is now to ensure the drivers of Innovation are in place by ensuring steady supply of talent and a critical mass of industries working in this domain with industry, academia and R&D coming together in defence SEZ supported by the enabling framework.

References

- Agamoni Ghosh, 2013, Business Standard, “Major labour strikes that shook the automobile industry” in www.business-standard.com/article/companies/major-labour-strikes-that-shook-the-automobile-industry-113041500150_1.html last accessed in 15.7.2015

- Anuj Agarwal, 2015, The Diplomat, “Do Productivity Gains Explain India’s Recent GDP Growth? ”

- CII, 2014, India Skills Report 2014, http://www.cii.in/PublicationDetail.aspx?enc=YW8drGDOtkyh75NmNOFWDJoJZxinduaCg/XmU4nENAw=, accessed on 15.7.2015

- deloitte , 2013, http://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/pages/manufacturing/articles/2013-global-manufacturing-competitiveness-index.html, accessed on 15.7.2015

- EY, 2014, “India’s cost of capital: A survey – Ernst & Young”, http://www.ey.com/Publication/vwLUAssets/EY-india-cost-of-capital-a-survey/$FILE/EY-india-cost-of-capital-a-survey.pdf, accessed on 15.7.2015

- FICCI, 2015, “FICCI Survey on Labour / Skill Shortage for Industry” http://ficci.com/SEDocument/20165/FICCI_Labour_Survey.pdf, accessed on 15.7.2015

- http://thediplomat.com/2015/03/do-productivity-gains-explain-indias-recent-gdp-growth/, accessed on 15.7.2015

- ihs, “Saudi Arabia Replaces India as Largest Defence Market for US, IHS Study Says” in http://press.ihs.com/press-release/aerospace-defense-terrorism/saudi-arabia-replaces-india-largest-defence-market-us-ihs- accessed on 15.2.2015

- imd, 2014, World Competiveness Ranking, http://www.imd.org/business-school/wcc/global-competitiveness-index.html last accessed in May, 2014 , accessed on 15.7.2015

- KPMG Report , 2010, Unlocking the Potential The Indian Aerospace and Defence Sector, www.kpmg.com/IN/en/…/KPMG_Indian_Defence_Industry.pdf, accessed on 15.7.2015

- PIB, 2013, “Review of the Economy 2012-13 – Highlights” , http://pib.nic.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=94914, accessed on 15.7.2015

- Tooling U-SME, A white paper, People Power: Human Capital Drives Manufacturing Competitiveness , http://www.toolingu.com/images/whitepapers/WhitePaper-HC-01152015.pdf last accessed in 15.7.2015

- world bank, 2015, “Doing Business in 2015”, http://www.doingbusiness.org/data/exploreeconomies/india, accessed on 15.7.2015