The Grey-Zone is predominantly a non-military arena wherein a Nation’s resources are employed to coerce a Target State (TS) into abiding by or not interfering with the aggressor’s core interests. Stated Grey-Zone objectives are achieved by the use of diverse, multi-pronged actions or approaches without obvious interlinks to evade accountability and which are mutually supporting and are below the threshold of conventional military operations. Elementally, Grey-Zone Operations (GZO) are operations that are neither ‘black’ nor ‘white,’ in terms of their threshold between war and peace and application (civil/military). The term ‘zone’ adds to the abstruseness of such operations which cover a wide range of covert/overt activities by an aggressor country as part of its statecraft.

A recent instance of China’s belligerence against perceived rivals occurred when the United States (US) Speaker Nancy Pelosi visited Taiwan in August 2022 in a visible endorsement by the US of support for Taiwan’s democracy. In response, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) condemned the visit through diplomatic channels. The days after the visit witnessed a series of military exercises in and around the Taiwan Strait, with frequent incursions over the median line. These actions were aimed at expressing resentment towards support for Taiwan’s cause by the US and its allies, while signalling to Taiwan the ramifications of opposing the One-China policy. China’s actions were an archetypal manifestation of ‘Chinese Grey-Zone Operations’ (CGZO).

A prior, but equally worrying CGZO incident occurred in March 2021, when around 220 Chinese fishing boats bearing the Chinese ensign anchored off the Whitsun Reef – part of the contested Spratly Islands in the Philippines’ Exclusive Economic Zone in the South China Sea. The Philippines claimed that these vessels were crewed by China’s maritime militia and, therefore, could well have been employed for surveillance or as a statement of belligerence and provocation, reinforcing China’s claims over these islands.

How Would CGZO Be Defined?

The Grey-Zone is predominantly a non-military arena wherein a Nation’s resources are employed to coerce a Target State (TS) into abiding by or not interfering with the aggressor’s core interests. Stated Grey-Zone objectives are achieved by the use of diverse, multi-pronged actions or approaches without obvious interlinks to evade accountability and which are mutually supporting and are below the threshold of conventional military operations. Elementally, Grey-Zone Operations (GZO) are operations that are neither ‘black’ nor ‘white,’ in terms of their threshold between war and peace and application (civil/military). The term ‘zone’ adds to the abstruseness of such operations which cover a wide range of covert/overt activities by an aggressor country as part of its statecraft.

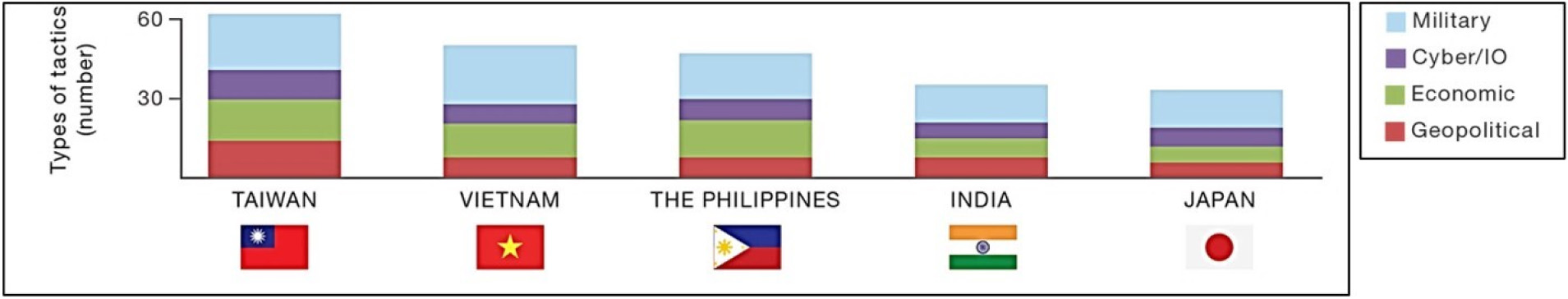

China, therefore, views CGZO as ‘natural extensions of …. exercise [of] power and [thus] employs such tactics to balance maintaining a stable, favourable external environment with efforts to alter the status quo in China’s favour without triggering major pushback or conflict’.[1] CGZO can be defined as ‘coercive Chinese geopolitical/economic/military/cyber and information operations (cyber/IO) activities beyond regular diplomatic/economic engagements and below the use of kinetic military force[2], to achieve stated objectives.

Chinese Military Helicopters fly past Pingtan Island, one of Mainland China’s closest points to Taiwan, during military drills after Nancy Pelosi’s Visit in August 2022.

(Source-npr.org/nbcnews.com)

What is the Likely Ambit of CGZO?

It is pertinent to look at CGZO in the light of the ‘Chinese Dream’ of achieving ‘Two Centenaries’- becoming a regional heavyweight in the present decade and an undisputed global power by 2049, the 100th anniversary of the founding of the PRC. While China has achieved the first goal, the latter would still necessitate use of all elements within its power – whether it involves ‘peaceful rise’ or the undermining of countries/alliances that it sees as competition/impediments in this journey.

CGZO are oriented towards the Chinese interpretation of the Zero-Sum Game, wherein China continues to gain politically, economically and geo-strategically with respect to a TS/region, by creating favourable conditions, while preventing the TS or its regional/global allies from unfavourably altering the status quo. CGZO are run as well-considered ‘campaigns,’ aimed at achievement of strategic results without resorting to direct conflict, or if the latter is inevitable in a future scenario, to shape conditions for success. Apropos, the last two decades have seen the PRC devoting substantial funds/effort towards enhancing CGZO capabilities globally, including its conventional/paramilitary strength that can be leveraged towards CGZO. Another important facet of CGZO is the choice of TS, which preferably need to be those that enjoy a pax stabilis or enduring peace, so that they do not fractionalise/go to war at the slightest provocation.

A recent study concluded that the past decade has seen more than 150 cases of non-military CGZO affecting 27 countries/the EU, with a sharp exponential increase in such operations since 2018…

CGZO are also collaborative and may be planned in conjunction with ‘allies.’ A pointer in this direction is the China-Russia Joint Declaration, signed on the opening day of the Winter Olympics in February 2022, wherein both countries pledged towards a ‘no limits’ partnership, including favourable recognition and mutual support over their respective positions on Ukraine and Taiwan, with a tacit assurance to act conjointly against Western interests.

China’s Modus Operandi (MO) for CGZO

CGZO are planned and structured to be incremental, a ‘bit-by-bit chiselling,’ in order to repeatedly create a new normal, the violation of or resistance to which by the TS will then be bandied as an ‘act of aggression.’ Different facets of CGZO can also be implemented concurrently to quickly respond to changing dynamics to ensure a greater chance of success.

One way to define the broad MO of CGZO would be to identify such operations by the actions entailed. These could include the following:-

- Non-military activities aimed at exerting ‘pressure’ in non-military domains- including leveraging regional alliances in proximity of the TS/garnering opinion against the TS on global platforms like UN/SCO/ASEAN+3 etc. China could also carry out such inimical activities directly against the TS in an overt manner, through geopolitical levers or economic coercion (EC), by taking advantage of its regional status. Grassroots-level CGZO forms an arm of CGZO, entailing covert actions within the TS/region by leveraging local proxies/rival political factions to take advantage of existing/perceived ethnic/ideological divides.

- CGZO could also take support from small-scale ‘salami-slice’ military tactics (referring to small, incremental actions to achieve a larger, strategic aim) to exert pressure on the TS without direct involvement, with the objective of coercing the latter to accept conditions favourable to China’s interests. Covert kinetic force, including the use of militia/unattributed military elements to conduct anti-National activities such as sabotage/assassinations in the TS/region, also cannot be ruled out.

Though CGZO would predominantly rely on non-military activities, its aim would largely remain coercive. China will unambiguously display its intent/desired ‘end-state’ and an abhorrence to any actions perceived to undermine its notion of being the ‘Middle Kingdom.’ Non-military CGZO would rely on tools such as cyber incursions/espionage, disinformation (e.g. via the Confucius Institutes/Chinese overseas talent-recruitment stations in various countries), political interference, diplomatic coercion (to include public condemnation/boycotts/threats at Government level and restrictions on trade/tourism/investments), EC/debt-dependency as a consequence of sanctions against TS/on specific companies and the ambiguous use of unconventional force to spread propaganda/germinate dissent/subvert individuals/groups and/or government functioning and ultimately coerce a TS into abiding by China’s external policy.

It is widely opined that increasing Chinese Naval presence, combined with ‘debt-trap’ diplomacy to assert ECover littoral TS (a classic example being Sri Lanka), has bolstered Chinese military presence in the region…

Another facet of covert CGZO could include globalization of China’s surveillance/coercion capabilities [akin to the Chinese Facial Recognition System] for identity exploitation/control, to target individuals of TS[3], akin to the alleged State-sponsored surveillance over the Uighur community in Western China. A recent study concluded that the past decade has seen more than 150 cases of non-military CGZO affecting 27 countries/the EU, with a sharp exponential increase in such operations since 2018.[4]

As regards targeting individuals, when Canada detained Huawei’s Chief Financial Officer in December 2018, China arrested two Canadian nationals on charges of security violations, who still remain in prison. Similarly, a citizen journalist has been imprisoned for ‘provoking trouble’ in Wuhanby reporting during the COVID-19 crisis[5], as has been an Australian journalist, under anti-espionage laws.[6]

CGZO would not be planned/implemented piecemeal, but would involve the highest Governmental organs, and would leverage support from the Central Military Commission, in a whole-of-Government approach. Some examples over the last decade are elucidated. In 2010, the Norwegian Nobel Committee nominated Chinese dissident Liu Xiaobo, then incarcerated for subversion, for the Peace Prize. Chinese criticism and a six-year diplomatic stalemate followed, with cessation of free-trade discussions, denial of official visas and a 92 percent reduction in Norwegian salmon imports! South Korea’s decision to allow deployment of the US Terminal-High-Altitude Air-Defence System in July 2016 met with similar coercive measures. The Dalai Lama’s visit to Mongolia in November 2016, resulted in suspension of bilateral talks and cancellation of a $4.2 billion debt-repayment loan to the country. In 2021, when Taiwan opened a Taiwanese Representative Office in Lithuania(a departure from the Taipei Representative Office in other countries), China responded with down gradation of diplomatic relations and food import sanctions – the latter leading to a 90 percent drop in food imports[7]. Chinese diplomatic coercion was witnessed in New Zealand in June 2022, when the Chinese Ambassador stated, in response to New Zealand’s perceived pro-US stance on Chinese issues that ‘an economic relationship in which China buys a third of a country’s exports, cannot be taken for granted’.

The Grey-Zone conflict between China and the US (representing China’s general antagonism toward the West) is a complex mosaic of minor Grey-Zone conflicts.[8] GZO here largely fall into the categories of cyber/IO, EC and the complexities related to the South/East China Sea (S/ECS). While ameliorative foreign policy still forms a part of China’s outlook towards the West, the PRC explicitly voices resentment over ‘unfavourable’ China-centric policies of the latter. An example is the recent visit of the US Secretary of State to China in June, wherein China declined the US offer to open military-to-military communication channels, citing US sanctions over Taiwan. Director of the CCP’s Foreign Affairs Commission Office and China’s top diplomat, Wang Yi, emphasized during the visit that ‘China has no room for compromise or concessions,’ thus reflecting the PRC’s unrelenting stance against contrarian US policies – all part of the diplomatic ‘arm’ of Grey-Zone coercion.

In the S/ECS, the PRC openly claims sovereignty over waters/islands and resources therein. China’s reclamation/militarisation of islands and belligerence, while asserting territorial sovereignty or while challenging actions of littorals/their allies and those of neutral powers in the region are frequently showcased. The establishment of the Chinese Air-Defence-Identification-Zone which includes the airspace over most of these contested areas and the sensitivity to the contested Spratly/Paracel Islands/the Island Chains/submerged reefs are testimony in this regard. Presence of PLA Navy/Coast Guard vessels and those run by the maritime militia is commonplace, both within and beyond China’s territorial waters. China is however, careful that such CGZO do not exceed the threshold of a TS’ military response. A PLA General has referred to a ‘cabbage strategy’-cloaking targeted islands with ‘concentric layers’ of Chinese civilian/military vessels to assert influence. Evidently, such coercive strategies aim to pressurise TS to rethink their geostrategic/geopolitical standpoints vis-a-vis China in the region. In case CGZO do not elicit the desired response, they could always be combined with/replaced by EC /military action, supplemented with IO/action against target populations/individuals.

India could strive towards the consolidation of India-US bilateral relations and the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue – a potentially effective tool against Chinese gunboat-diplomacy and a platform for coordinated counter-CGZO IO…

CGZO in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR), with the exception of the Indian Subcontinent, are less brazen. Peacetime maritime activities have been predominant, with no obvious violation of littoral EEZs and International Maritime Laws. That said, China has significantly expanded its activities in the IOR over the last three decades. It is widely opined that increasing Chinese Naval presence, combined with ‘debt-trap’ diplomacy to assert EC over littoral TS (a classic example being Sri Lanka), has bolstered Chinese military presence in the region. CGZO MO here would include the following:[9]

- Non-combat activities including soft loans/infrastructure development, to protect Chinese citizens/investments, while enhancing soft-power influence.

- Unilateral/partnered counterterrorism activities, against threats to China’s demographic cohesion, e.g. against terrorist organisations that support the Uighur freedom movement or those that create unrest within the Tibetan Autonomous Region.

- Coercive diplomacy towards small countries.

- Intelligence operations/IO in support of operational requirements in case of conflict with a key adversary TS.

- Build ability to pre-empt/deter actions to interdict China-bound trade, and to threaten adversary trade in the event of a wider conflict.

In the PRC’s perception, CGZO is indispensable for resolution of territorial claims in the region. China, unlike in the S/ECS, exercises caution in overtly wielding expansionist power here and relies more on third-party proxies and regional/global cooperative platforms rather than direct coercion, especially when it comes to large economies such as India. China, therefore, sees its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) infrastructure projects in South Asia as a subset of CGZO/complementary to its security aspirations. The latest example is their use of Private Security Companies along the BRI (as in Africa), allowing China to protect its projects/nationals, while undermining access by the TS to natural resources, with plausible deniability.

For the last decade, China has indulged in grassroots-level CGZO here, by way of recruiting local proxies/cyber operations/IO. A distinguishing feature of CGZO here is the penchant for territorial expansionism against regional neighbours including India – a consequence of the large number of countries that share land borders with China. The June 2020 Galwan incident and incursions across the Line of Actual Control (LAC) with India, are a testimony to this fact, though China has kept military operations below the threshold level that would lead to an all-out conflict.

An example of the flavour of CGZO in the region is the hacking of Mumbai’s power grid in October 2020, allegedly by a Chinese State-sponsored hacker group, which was effective enough to trip the grid, disrupt rail movement and severely affect online operations. The New York Times of February 28, 2021, stated this was a warning from China for the misadventures in the Galwan Valley and for India’s territorial claims in the region.

It is pertinent to note from the above figure that recognised CGZO against India (~35) are far less than those against Taiwan (~60) and against TS in East/Southeast Asia.

As a fall-out of China’s ‘neighbourhood first’ policy in the IOR, the PRC has made attempts to forge bilateral geostrategic/economic partnerships with regional States. Joint military exercises, soft loans, defence equipment sales on credit-lines and participation in Humanitarian Assistance/Disaster Relief (HADR) related activities are attempts towards such outreach. However, countries must exercise propriety in accepting such offers, lest these quickly be leveraged as debt-traps/basing opportunities by China.

Grey-Zone operations represent an unobtrusive, yet relatively inexpensive method of furthering a nation’s interests…

What Could Be Suggested Counters to China’s Grey Zone Operations?

CGZO are a ‘whole-of-Nation problem,’ requiring a ‘whole-of-Government response’ by a TS. While it may be possible to regularly, if not infallibly, identify/recognise CGZO activities, planning/implementing timely counters pose a greater challenge – there being no templates for a counter-CGZO OODA cycle. One suggested MO could be:

- Source intelligence inputs to identify CGZO/assess their efficacy. This implies quantitative intelligence (level of Chinese State involvement/level of attempted penetration within a TS’ hierarchy/machinery) and qualitative intelligence (individual facets of CGZO employed), to infer the likely efficacy of planned counter-CGZO activities.

- Assess the spread of CGZO – within own country and regionally/globally. The former will determine the urgency/priority of implementing CGZO counters. Collaborative counters must be considered if the CGZO has regional/global reach. Such counter-actions would necessarily include intelligence collaboration/EC/diplomatic ‘strong-arming’/IO.

- Assess degree of difficulty of planned counters, in terms of effort/finances/time required.

- Identify most effective counters in terms of effort/implementation time/effectiveness. Plan sequence of implementation/concurrent launch of counters, depending upon the earlier pointers.

- Back up with well-considered IO campaign.

A counter against the threat of economic sanctions should leverage the fact that the total import trade from TS to China has been close to $60 billion.[10] These countries can, therefore, practise collective punitive economic deterrence by diverting their exports, should China indulge in coercion against all/some/one of these countries. At the geopolitical/diplomatic level, a TS (India hereinafter) must look towards allies/China’s rivals to forge strategic alliances. India could strive towards the consolidation of India-US bilateral relations and the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (QUAD) – a potentially effective tool against Chinese gunboat-diplomacy and a platform for coordinated counter-CGZO IO.

Internally, with respect to cyber operations/IO, India’s existing national crisis-management mechanisms – the National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) and the National Disaster Response Force, must be regularly drilled and ‘stress-tested’ in counter-CGZO. It is, therefore, imperative that training institutions such as the National Institute of Disaster Management be regularly fed new CGZO MO from intelligence agencies including Research & Analysis Wing and National Technical Research Organisation. Such training, in addition to personnel of these agencies, must also be provided to the Armed Forces/Government Ministries/organisations including MoD/MEA/Ministry of I&B, as well as private vendors in the IT/media industry, among others. A lead Ministry must be nominated to coordinate counter-CGZO activities, viz the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA), the MoD, or any other nominated Ministry. The NDMA, under the MHA can also be assigned the responsibility for protection of cyber-critical infrastructure. This would necessitate involvement of the Indian Computer Emergency Response Team (CERT-IN) and National Critical Information Infrastructure Protection Centre (NCIIPC), for state-of-the-art response/technical support. Military SIGINT/COMINT must also be sourced for inputs. NDMA could assume the role of peoples’ advisory, to disseminate missives regarding CGZO\grassroots-level counters to the population via existing multi-media platforms. Such a focussed organisation would enable India to not only deter CGZO forays, but allow for retaliatory ‘offensive’ actions, as a combination of intelligence gathering/cyber operations/IO/demographic subversion in sensitive regions within the Chinese mainland, aimed towards undermining the CCP’s inimical ideology towards the region. All such offensive counter-CGZO operations should aim to achieve ‘Grey-Zone deterrence,’ or the capability to dissuade China from indulging in CGZO.

Traditional military coercion is unlikely to work against deniable Grey-Zone activities. However, since CGZO might be used for environment-shaping preceding hybrid-warfare of which CGZO would be a part or all-out conflict, the Indian Armed Forces must form a part of the counter-CGZO OODA cycle and military planning must continue to keep abreast with counter-CGZO efforts. More routinely, the Indian Armed Forces would need to be involved in high-visibility collaborative exercises with China’s perceived rivals/in regional HADR tasks, to win political favour/demographic support and erode CGZO attempts to cultivate ‘friendly’ States/grassroots-level proxies. Such counter-CGZO support would also include enhancement of boots-on-ground/aggressive posturing to counter China’s actions of ‘salami-slicing’ along the LAC. Military Attaches in other countries can be instrumental in nurturing serving/retired foreign military staff/students who have had tenures/attended courses/exercises in India, to favourably portray the Indian cause vis-a-vis China.

Conclusion

Grey-Zone operations represent an unobtrusive, yet relatively inexpensive method of furthering a nation’s interests, without the level of direct provocation that would lead to all-out war. Deniability and disownment are the cornerstones of such cloak-and-dagger strategies, which have today become the ‘new-normal’ of conflict.

Endnotes

[1]https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA594-1.html

[2]https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_briefs/RBA594-1.html

[3] US Defense Science Board April 2023 Edition on New Dimensions of Conflict: https://dsb.cto.mil/reports/2020s/DSB-SS2020_NewDimensionsofConflict_Executive%20Summary_cleared.pdf

[4]https://maritime-executive.com/editorials/the-evolving-risk-of-china-s-gray-zone-operations

[5]https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-59544226

[6]https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/apr/27/china-widens-already-breathtaking-scope-to-arrest-foreigners-for-espionage

[7]CSIS Report- Deny, Deflect,Deter-Countering China’s Economic Coercion

[8] The Gray Zone Issue: Implications for US-China Relations:https://pacforum.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/issuesinsights_Vol19WP14.pdf

[9] China’s Indian Ocean Ambitions- Investment, Influence, And Military Advantage : https://pacforum.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/issuesinsights_Vol19WP14.pdf

[10]CSIS Report-Examining China’s Coercive Economic Tactics :https://www.csis.org/analysis/examining-chinas-coercive-economic-tactics