“As for the revolution in soldiery, the competition between the military forces is moving to outer space here…. This is historically inevitable, and this development cannot be reversed. The PLAAF must formulate a modern day idea of security area, area of interests and exploration of space. We must develop space troops which would meet the demands of development of our country and demands of the space age. Superiority in outer space can give a country the control over military zones on the land and at sea in addition to the expected strategic superiority. Superiority is simply necessary to defend the nation and state. After all, only a strong power can defend peace.”

—Xu Qiliang, PLAAF Commander1

In January 2007, China carried out an ASAT test. Exactly three years later, in January 2010 it surprised the world by intercepting an incoming missile in an exo-atmospheric test. Earlier, China had launched a manned space mission exactly as planned on October 15, 2003. More recently, China has officially announced that it has modified a MRBM for anti-shipping role thereby demonstrating her capability to accurately manoeuvre the MRBM in its terminal stage to hit a moving target the size of a large aircraft carrier. China’s space exploration and moon missions continue apace.

China’s overall national strategy has not changed from the time the Communists won the Civil War and Mao Zedong proclaimed the birth of the PRC…

Since the launching of her first satellite in 1970 the PRC has launched over a hundred satellites and has some 20-30 of them in orbit at any one time and will soon complete a regional network of navigation satellites comprising three geo-synchronous and twenty-two medium earth orbit satellites. In January 2011, China launched her own version of the Fifth Generation Fighter Aircraft (FGFA) on its first flight while Robert Gates the then US Secretary of Defence was on a visit to China.2 Considering that China was a late entrant on the aviation scene and was also at the receiving end of technology denial regimes for a long time these achievements are even more remarkable. China’s interest in South China Sea goes back to 1947. She claims the well-known ‘U’ shaped broken line shown on the Chinese maps as Chinese territory; this area of the sea has recently been designated as a ‘district’ of China. Hence China also claims all rights to exploit undersea mineral resources in the extended exclusive economic zone effectively demanding control of the entire South China Sea. China also wants the US and the world at large to acknowledge ‘the South China Sea’ as a ‘core issue.’

This Chinese behaviour should, however, not surprise us. In 1959, Nehru had remarked, “India had to face a powerful country bent on spreading out to what they consider their old frontiers and possibly beyond. The Chinese have always, in their past history, had the notion that any territory which they once occupied in the past necessarily belonged to them subsequently.”3 Making absurd claims on territories and then stating that it was ready to resolve the issue through peaceful negotiation should by now be a well-known Chinese tactic. Simply stated, China is an expansionist power and is now determined to use her Comprehensive National Power (CNP) to announce to the world that it has arrived.

China’s overall national strategy has not changed from the time the Communists won the Civil War and Mao Zedong proclaimed the birth of the PRC on October 1, 1949. He said, ‘China had stood up’, clearly telling the world not to mess with it. The aim obviously was and is to strengthen China so that it never again suffers the humiliation of the previous century. Mao’s decision to enter the Korean war in support of North Korea, her invasion of Tibet in 1950 and efforts to reunify Taiwan are all part of that strategy. Although Mao called nuclear weapons ‘paper tigers’ he nevertheless pursued a robust nuclear development programme in the 1950s and built and tested the atomic bomb on October 16, 1964. Those working on missiles and nuclear weapons were spared the excesses of the Cultural Revolution.

China has also attempted to build a loose coalition of states that are generally antagonistic to America and has very nearly succeeded in keeping India boxed in South Asia…

By October 1967 the PRC had tested a hydrogen bomb and soon developed the necessary delivery means. Since the early 1990s, PRC’s impressive economic progress has given the Chinese leadership the necessary resources to modernise her armed forces and space capabilities but it has also made her increasingly more dependent on energy imports. Free and uninterrupted access to and use of undersea resources in South China Sea are, therefore, an essential part of that strategy.

China has also attempted to build a loose coalition of states that are generally antagonistic to America and has very nearly succeeded in keeping India boxed in South Asia and hence her consistent support to Pakistan, Iran, North Korea and other such powers. The Communist leadership, however, is also acutely aware of China’s domestic problems and conscious of the critical need to reduce regional economic inequalities and ensure stability. To achieve this it counts on the ‘nationalism’ of the Chinese population knowing full well that without sustained economic prosperity this objective cannot be achieved as the people would not blindly follow the dictates of the CCP. But invoking nationalism and past humiliation at the hands of foreign powers can work only up to a point.

As a result, the Chinese leadership tries to ward off threats to national security by continuously maintaining and cultivating an image of a strong yet peaceful developing country that is only interested in improving the lot of her people. China’s goal of becoming a peer competitor to the US requires reducing American interference in Asia without actually resorting to use of force. Centralised and seamless control over all national activity, the relatively long and uninterrupted tenures of national leaders and collective decision making as in the CMC help the leadership to pursue long-term strategic plans. China’s air and space strategy thus neatly fits into her overall strategy.

PLAAF Growth

The PRC signed a Friendship Treaty with the erstwhile Soviet Union on February 14, 1950, entered into a very beneficial military cooperative relationship with the former Soviet Union and begun building a variety of arms of Soviet design in very large numbers. China’s experience of the three-year-long Korean war gave added impetus to its quest for modern arms, especially aircraft, tanks, artillery and missiles and also the urgent need to develop its own nuclear weapons to face the threat of nuclear blackmail. Mao’s famous words, “Even if 300 million Chinese die in a nuclear attack, 300 million more will remain and start a new glorious revolution” can be interpreted as China’s answer to future nuclear blackmail.

Mao’s famous words, “Even if 300 million Chinese die in a nuclear attack, 300 million more will remain and start a new glorious revolution” can be interpreted as China’s answer to future nuclear blackmail.

Mao’s policies of social engineering, experiments such as ‘The Great Leap Forward’ (1958-61) resulted in a major setback to China’s future plans. His insistence on self-reliance, his strong belief in the superiority of man over machine and the policy of increased agricultural output and steel production in rural homes devastated large tracts of the hinterland and caused widespread famines as millions of uneducated farmers diverted their energies from agriculture to produce low-quality steel in rural households. The 10-year-long Cultural Revolution (1966-76)4 saw thousands of ‘intellectuals’ such as university professors and students, engineers and educated citizens being forced into farming rural lands by Mao’s radical Red Brigades effectively putting an end to any meaningful research and development.

Until the early 1980s the PLAAF was in a bad shape. It had some 5000 aircraft but most of these were either obsolescent or suffered from poor serviceability such that the average pilot could not get the necessary minimum training. There was widespread instructor shortage and the PLAAF’s flight safety record was also poor. One of the main reasons for this state of affairs was her leadership’s insistence on self-reliance when China simply did not have the technology to produce modern aircraft and weapons at home.

The story of PLA modernisation, however, really began with the end of the Mao era. With the demise in quick succession of both Zhou Enlai and Mao Zedong in 1976, Deng Xiaoping came to the helm after a relatively brief power struggle. Once the ‘Gang of Four’ was taken care of, Deng could move with his revitalised and revised plan of ‘four modernisations’ without too much opposition from the other members of the Party. The Deng mantra was that for socialism to succeed China had to first improve its economy so that it could lift the living standards of its people and generate the necessary surpluses to fund its modernisation plans. He was prepared to adopt capitalism with ‘Chinese characteristics’. He famously said, “The colour of the cat was immaterial so long as it caught mice.” The new ‘four modernisations’ programme included agriculture, industry, S&T and military. While in the initial period of China’s opening up, the military was indeed given a lower priority with the defence budgets seeing major reductions for a decade that did not mean a total neglect of the armed forces.

By 1985, Deng Xiaoping, the paramount Leader had discounted the threat of a major war, nuclear war or world war but had stressed the possibility of a high intensity, short duration local border war. From the 1990s onwards the defence budgets began to rise and soon thereafter maintained a double digit growth rate up to the present times. As a result, the PLA benefited from large scale arms imports and a steady growth of indigenous defence industry. The PRC leadership also benefited from the advice of the then US Under Secretary of Defence William Perry and focused on building a strategic industrial base.

Being almost as large as the US, the PRC enjoys strategic depth and its leadership knows that their country cannot be occupied or defeated. Deng was equally conscious of the importance of modern air power.

There, however, were many hurdles to this rapid progress; the most important being the internal debate on self-reliance versus direct imports. The PRC leadership was divided on self-reliance but was united on the final objective of military reforms. China’s goal was to not only modernise its armed forces but more importantly to build its indigenous strategic industrial base so that it could ultimately become a leading exporter of modern weapons and equipment because without such a capability it could not be counted among major powers. Its leadership also showed maturity and wisdom in the selection of weapons to be bought from foreign vendors and those to be manufactured at home. The gradual if slow evolution of China’s military doctrine also played a significant role in this process.

The 1991 Gulf war came as a ‘rude wake-up call’ to the PRC/PLA leadership although the PRC President Yang Shangkun appeared to belittle the relevance of American military might to his country: “The model (of the Gulf war) is not universal. It cannot be applied in a country like China, which has a lot of mountains, forests, valleys and rivers. Another characteristic of this war is that the multinational forces faced a very weak enemy.”5

In fact, the US and North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) allies have fought all wars of the past two decades against militarily weak powers. Even so, the changing nature of modern warfare and the advances in the application of air and aerospace power were not lost on the Chinese. Being almost as large as the US, the PRC enjoys strategic depth and its leadership knows that their country cannot be occupied or defeated. Deng was equally conscious of the importance of modern air power. “The army and the navy both need air cover. Otherwise, the enemy air force will run rampant.”6 Here again the overall tenor appears to be defensive but this was to change soon. In a 1997 conference of senior military commanders the then President of the Academy of Military Sciences said, “The very assembly and deployment of ‘coalition forces’ constituted the ‘first firing’ and justified pre-emptive military action.”7 The collapse of the Soviet Union and the ensuing economic problems of that country were very cleverly used by China to employ a large number of Russian engineers and technology experts and to purchase relatively modern weapons such as the Su-27 air superiority fighters, Sovremenny class destroyers and improved Kilo Class submarines.

First the lessons of the 1991 Gulf war and later the 1999 Kosovo conflict, the 2001 Afghanistan and 2003 Iraq war where air power and space technologies played a vital role have only reinforced PRC thinking on the efficacy of modern air power. Not only was the PLA changing its military doctrine and strategy, its national leadership was now compelled to admit that without a comprehensive overhaul of the equipment of its armed forces China could not assure national security. Thus began in earnest, in 1992 the process of PLA modernisation which continues till date.

China’s Space Programme

While the immediate management of the Chinese Space Programme (including commercial aspects) is exercised by the China National Space Administration it is subordinated to the PLA’s Main Directorate of Armament.

The PRC has so far launched some 100 satellites into low, medium and geostationary orbits covering all traditional areas such as communication, navigation, weather, surveillance, reconnaissance, and other special use variety.

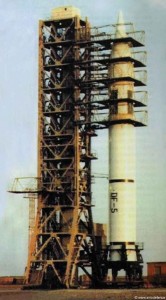

The Chinese space programme began to develop at the Shuangchengzi missile range which eventually became a space launch centre is situated in the Gansu province in the Gobi desert. Its official name is Jiuquan Satellite Launch Centre but the PLA calls it Base 20. It was built in 1958 for the launch of the Dongfeng (DF) family of Inter Continental Ballistic Missiles (ICBMs). The first Chinese satellite DFH-1 was launched from here on April 23, 1970, and on October 15, 2003, the first manned spacecraft Shenzhou was also launched from this spaceport. The area of this missile range is 19,600 sq kms.

The second spaceport of Wuzhai — also known as the Taiyuan Satellite Launch Centre or Base 25 — is in the province of Shanxi and is operational since 1967. The Xichang spaceport or Xichang Satellite Launch Centre or Base 27 is located South-Southwest of Chengdu in Sichuan province and is operational since 1970. Due to its proximity to the equator most of the launches have been taking place from this launch centre. Another spaceport is under construction near Wenchang on Hainan Island and is expected to be ready by 2013. Due to it being further South, it will be used to launch heavy spacecraft up to 25 tons. The Chinese Mission Control Centre is at Xian in Shanxi province.

Like other space powers, China also initially developed its carrier rockets from military ballistic missiles. The first carrier missile, the Changzhen-1 (CZ-1) was developed from the Dongfeng-4 (DF-4) ICBM. Later the DF-5 became a predecessor for the CZ-2C/SD carrier rocket with a launch weight of 213 tons. The much more powerful CZ-2E followed with a launch weight of 460 tons and was equipped with four additional first stage boosters with the capability to send a 3.5-ton payload into a geosynchronous orbit. The CZ-2F a modified CZ-2E eventually took the first Chinese manned spacecraft. The CZ-3 derived from CZ-2C used a cryogenic third stage with the CZ-3B becoming the most powerful rocket capable of taking a 12-ton payload into a low orbit. CZ-4 and CZ-5 under development are expected to take much heavier loads 25 tons to a low orbit and up to 15 tons into a geosynchronous orbit.

The PRC has so far launched some 100 satellites into low, medium and geostationary orbits covering all traditional areas such as communication, navigation, weather, surveillance, reconnaissance, and other special use variety. Some 20-30 satellites are currently in orbit. In 2010, China launched the second of the three geosynchronous satellites for the Beidu navigation satellite programme that will eventually have some 22 medium earth orbit satellites and provide GPS Global Navigation System (GLONAS) type of navigation facilities over China and adjoining areas. The manned space flight project was launched in 1992. During 1992-2002, four unmanned launches of the spacecraft Shenzhou weighing 7.5 tons were undertaken. Since October 15, 2003 a total of four such missions have been launched with a spacewalk being performed by a Zhai Zhigang in a Chinese made spacesuit. China plans to establish a space station in the near future.

In spite of the PLAAF and PLAN possessing such a large number of third generation or even slightly more advanced fighters, it is not clear if these would be used in their traditional roles.

As with other Chinese military projects, secrecy shrouds her military space programmes but it is evident that China is determined to make full use of space for her strategic purposes. According to a Russian analyst, the Chinese know that American military superiority is based largely on network-centric warfare, the ability to launch PGMs and collect massive amounts of intelligence, all of which are dependent on space-based assets. Without these they are reduced to being mere ‘platforms’. China’s ASAT test of January 2007 should be seen in this light. With China also focusing on cyber warfare as part of ‘informationisation’, her final objective is to develop asymmetric capabilities to match US power without trying to enter an arms race.

The PLAAF Challenge

According to the latest reports (IISS Military Balance, March 2011) the PLAAF has some 1687 combat capable aircraft up from 1653 the previous year. The Chinese aviation industry now has the capacity to manufacture 40-50 modern fighters every year. Such is the pace of progress that the Chinese have of late relied less on Russian technology.

The PLAAF, however, has almost no combat experience nor has it participated in major exercises with other air forces. Yet, the trajectory of PLA modernisation and the focus on cruise missiles, Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) and Unmanned Combat Aerial Vehicle (UCAV) and space-based systems such as the GPS/GLONAS reconnaissance satellites shows that the PLAAF is by no means lagging behind other air forces in its understanding of the concepts of air power employment. A majority of the 1687 combat aircraft, however, are of II/III generation with only some 144 J-10 and a few Super-10, 243 Su-27/30, 72 JH-7A while the rest comprise J-7 and J-8 of the older generation.

In addition the PLAN’s aviation wing has some 311 combat capable aircraft with 24 Su-30 Flanker and 84 JH-7 fighter bombers with the remaining comprising J-7 and J-8 variants. Some 15 J-15, a locally manufactured version of the carrier-borne Su-33 are to join the PLAN’s new aircraft carrier the Varyag.

Simultaneous and well-coordinated offensive operations by China and Pakistan are a remote possibility but one for which the country must be prepared.

In spite of the PLAAF and PLAN possessing such a large number of third generation or even slightly more advanced fighters, it is not clear if these would be used in their traditional roles. Given the strong influence of Sun Tzu’s philosophy of ‘winning wars without actually fighting’, the hangover of the People’s War dogma, PLA Army’s domination and the relatively limited combat experience of the PLAAF, there is a possibility that the Chinese leadership will rely more on the country’s missile force, especially the conventional SRBM of the M-9 and M-11 variety in preference to combat aircraft.

These weapons are available in large numbers and could well be used in the opening phases of a border conflict to convey Chinese political resolve and to avoid attrition to own fighters. The terrain, large distances to airfields in Sichuan and Yunnan provinces (1,600-1,800 km from Arunachal Pradesh to Chengdu and Kunming) and the limitations imposed by high altitude on fighter operations from Tibetan airfields could also force the Chinese to bank on conventional missiles — SRBMs. It is also debatable if on their way to targets in India the Chinese aircraft would be allowed to overfly Myanmar and/or Bangladesh. For example, as the crow flies, Mandalay which has a very long runway is 805 km from Kolkata, 821 km from Tawang and 1,913 km from Chennai. The Great Coco Island that has only a 1,300 metre long runway is just 284 km from Port Blair.

Given the very large distances to their launch bases in mainland China and the severe payload limitations on fighter operations from the high altitude airfields in Tibet the actual offensive capability of the PLAAF along India’s Northern borders is somewhat limited. The PLAAF fleet of Flight Refuelling Aircraft (FRA) is neither large enough nor sufficiently trained to compensate for this limitation. Besides the airfields in Tibet can be easily targeted by the Indian Air Force (IAF) and hence would remain vulnerable.

In view of the above, the PLAAF may well be the instrument of first choice in a future conflict against Taiwan or in the Yellow/South China Sea but is unlikely to pose a major challenge along the Northern borders of India for some years before China’s FGFA becomes operational.

Capabilities of IAF

The IAF today has a fairly large number of combat aircraft and a small number of conventional missiles of the Prithvi class. In the past, India has shown some reluctance to employ offensive air power in right measure. The combat elements of the IAF were simply not used for fear of escalation during the 1962 Sino-Indian border war which India lost. Thirty-seven years later in the 1999 Kargil conflict, the use of air power was delayed and then severely restricted to the Indian side of the Line of Control again for fear of escalation. It is, therefore, essential that the country’s military and political leadership is prepared to demonstrate India’s resolve without which all the expensive hardware would be utterly useless.

China has largely succeeded in strategically encircling India and has also strengthened her relations with India’s neighbours by giving them generous military aid.

IAF resources would undoubtedly be stretched in the event of the Pakistan Air Force (PAF) also mounting an offensive in collusion with the PLAAF. But even in such a situation it would not be easy for them to prevail. Simultaneous and well-coordinated offensive operations by China and Pakistan are a remote possibility but one for which the country must be prepared. For a variety of reasons, at present neither China nor India is likely to engage in an all-out, copy-book and set-piece conventional war. Firstly, India has consistently avoided using force even in the face of serious provocation from Pakistan. Secondly, for China, Taiwan and South China Sea disputes may be of far greater strategic importance given the recently reaffirmed American interest in the region. This is not to suggest that unrest in Tibet and Xinxiang does not pose a threat to China’s national unity. Thirdly, China is no longer the isolated country of the early Cold War era. Today, China is an important economic power with worldwide trading interests and can hardly afford to sully her image as a responsible player. Fourthly, China’s dependence on maritime routes for exports and energy imports especially through the Straits of Malacca would also constrain her strategic options.

The possibility of a local border skirmish, however, cannot be totally ruled out. In such a scenario India must sharply restrict the scope of such a skirmish. Combat elements of the IAF must be used quickly and effectively to demonstrate India’s determination and resolve.

There also exists a possibility of a face off in South China Sea where China has strongly objected to ONGC-Videsh undertaking oil exploration in collaboration with Vietnam. In response, the Indian Prime Minister has stated that this is a purely commercial activity clearly reaffirming India’s determination to assist Vietnam. In the event of a conflict the PLAAF and IAF would have to use flight tankers as this area is at considerable distance from their mainland bases. India has little choice but to station a Su-30 squadron at Car Nicobar airbase in A&N Islands for any possible action in the vicinity of the Malacca Straits.

Conclusion

The Chinese air and space assets are undoubtedly growing at a rapid rate. The PRC’s strategy is essentially aimed at the US. China does not want the US to intervene in a future conflict with Taiwan nor does she want to lose her freedom to bilaterally resolve the South China Sea disputes. China has largely succeeded in strategically encircling India and has also strengthened her relations with India’s neighbours by giving them generous military aid.

While India must continue to further improve her relations with China it will also have to show the necessary firmness and willingness to resort to use of force if it becomes inescapable.

China has recently announced the establishment of a refuelling base in Seychelles and has maintained her naval presence around the Horn of Africa for anti-piracy operations. China would fully use and deploy her space based assets in South as well as Southeast Asia for Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance (ISR) activity and resort to probing actins along the disputed borders and elsewhere to test India’s resolve and keep her on the back foot. India cannot thus afford to let her guard down.

Two recent statements by Indian political leaders give a fairly good idea of the current state of Sino-Indian relations. On November 30, 2011, Defence Minister AK Antony admitted that the PRC had created some, “situations along the Line of Actual Control (LAC) that could have been avoided but which were due to different (sic) perception of the border” that remains un-demarcated, but these were resolved through established mechanisms such as hot line, flag meetings, meetings of the commanders of the two sides and that the Sino-Indian border is quiet and tranquility is maintained.

On December 4, 2011, Mr Omar Abdullah, the J&K Chief Minister expressed concern over Chinese involvement in the Kashmir region and wanted, ‘India to show spine’ while dealing with China. Even the normally mild mannered Dr Man Mohan Singh, the Prime Minister of India, has said, “China has been getting more assertive” and that “China wanted to maintain a low-level of equilibrium with India.” This clearly shows that keeping Sino-Indian relations at a comfortable level would remain problematic. India would have to build her economic and military strength to face this challenge. It will be a tight rope walk.

Notes

- Xinhua News, November 4, 2009, on the eve of the 60th anniversary of the PLAAF.

- This was apparently because Gates had doubted China’s ability to produce a fifth generation fighter before 2020.

- Srinath Raghavan, War and Peace in Modern India, A Strategic History of Nehru Years, (New Delhi, Permanent Black, 2010), p. 257.

- Officially launched by Mao Zedong on May 16, 1966 it ended by late 1969, but most observers feel it continued until the end of 1976 when Lin Biao (deceased in 1971 flight accident) and the ‘Gang of Four’ were held responsible for many of its excesses.

- Lewis John Wilson and Litai Xue, China’s Strategic Sea power, (Stanford, CA, Stanford Press,1993), p. 89.

- Lewis John Wilson, “China’s Search for a Modern Air Force,” International Security, Vol. 24, No. 1 (Summer 1999), p. 73.

- Ibid., p. 92.

I am genuinely glad to reaad tthis website posts which includes plenty off valuable information, thanks for providing these kinds of data.