Despite Nehru’s optimism and high profile in international conference diplomacy in the Far East, Indo-China and in Geneva and New York regarding nuclear, disarmament and peacekeeping issues, India’s position in the South Asian region was affected negatively by regional events and developments. These events were beyond the control of Nehru and his colleagues. The strategic initiative lay with forces outside India’s borders which nonetheless affected Indian interests. But did they alter the thinking and policies of the Indian government? What was the rate of change on the Indian side in response to these developments?

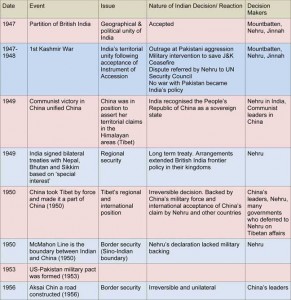

I argue that the Indian responses showed the reality of India’s subordinate state system position. In this position leadership and elite knowledge of external forces is incomplete and policy making is vulnerable to external intelligence inputs; internal checks and balances to correct faulty information and decision-making do not exist, and inertia prevails and leads to reiteration of the known policy lines and preferences. Table below lists the external developments which affected Indian security interests and position in the early 1950s.

The rate of change was rapid in India’s environment during 1947-56 which was adverse to Indian strategic interests and which reduced India’s ability to manoeuver diplomatically in regional international relations. 1. India became an active field of regional and international power politics.

Jinnah’s decision to allow the tribal invasion of J&K in 1947-48 made the northern border state a point of serious threat to Indian interests.

It showed that following Partition Jinnah wasted no time to take the strategic initiative against India and to mobilise the Western world to his side. His actions had multiple effects. It nourished separatism in Kashmir among the Muslim majority. It encouraged communalism in India. It complicated the governance of J&K, particularly with the population in the Srinagar valley. It enabled Pakistan’s political and military leaders to maintain the view that Pakistan as a territorial state and Islam as a religion was under permanent threat from the Hindu majority India. It enabled Pakistan’s leaders to maintain Pakistan’s territorial claim to Kashmir and it was a tool to fragment India’s territorial unity and cut it to size. Its position on Kashmir dispute was also a way to promote the position of Pakistan as the guardian of Islam in the subcontinent and the guardian of Indian Muslims residing in India after 1947.

…following Partition Jinnah wasted no time to take the strategic initiative against India and to mobilise the Western world to his side.

The start-up of Islamist militancy and terrorism in the 1980s was a logical corollary of the Pakistani belief – shared by the population and the elites – that Kashmir belonged to Pakistan by virtue of religion and the historical pattern of trade and economic geography.

By virtue of her population, geographical size, political organisation, democratic values, secular views and internationalist outlook, India was supposed to be the rising new power in the third world and in East-West, North-South affairs. Indian Muslims had been the dominant power in India as the Mughal Emperors who ruled India before the ascendency of the East India Company.

Pakistan’s policies after 1947 indicated that it sought a return to former Muslim glory by a policy of cutting India to size by unilateral warlike campaigns and/or by organising international pressure – through their alliance with USA and the combined use of Pakistani, American and other Western diplomatic efforts at the UN to accommodate Pakistani claims to regional security in Kashmir. Here Pakistani strategic and diplomatic interest was to align itself to Western concerns with the threat of the spread of Russian communism into the Middle East and South Asia; the second interest was to align her diplomacy and military policy to her cultural belief in the cultural superiority of the Muslims of the subcontinent.1

It manifested itself in two ways: one, that it was intolerable that Hindus should rule the subcontinent and the Muslims; two, it was desirable to restore Muslim glory after 1947 by policies of military interventions and diplomatic alliance building activity with Western (and later Chinese) powers. These attitudes and policies of Pakistan indicated that it viewed itself as a re-emerging power in the region, given its strategic location for participants in the Cold War and great power politics in the early 1950s.

…Pakistan, the geographically smaller state in relation to Indian resources, emerged as the strategic trigger vis-à-vis India that placed India’s leadership and government in a reactive and defensive mode.

Here Pakistan, the geographically smaller state in relation to Indian resources, emerged as the strategic trigger vis-à-vis India that placed India’s leadership and government in a reactive and defensive mode. Chapter 5 of the book “India’s Strategic Problems” explains the pattern of Pakistani-Indian interactions and the respective worldviews that underlined the inherent antagonistic relationship between the two countries.

The second source of the rapid rate of change lay in China’s military expansion into Tibet in 1950. It made it a part of China, and although Nehru was uncomfortable with the turn of events he acquiesced in China’s decision urging it however, to respect Tibetan autonomy and culture. Many countries in the Western world deferred to Nehru’s judgement on Tibet and Nehru himself sought to slow the process of Tibet’s integration as a part of China by working diplomatically with Chinese premier Zhou Enlai. The history of China’s push into Tibet is well known but less known is the role Nehru played in diplomatically facilitating China’s position in the region and in undermining the position of the Dalai Lama and the Tibetans.

Chapter 6 of the book “India’s Strategic Problems” provides the unpublicised story of the Nehru-Zhou collaboration between 1950 and 1959 in this respect. American writers familiar with Tibetan affairs of the period have published materials on the subject but Indian archives are still closed to academic research. There are two stories involving Nehru. One, that Nehru worked with Zhou in the hope that Chinese rationality would let them act humanely in Tibet. Two, when the Chinese military juggernaut could not be stopped in pushing aggressive political and cultural activities along with military pressure to marginalise the Tibetan spirit and to build a domineering Han presence in the region, then Nehru agreed to support covert American action in Tibet.

The US-Pakistan military pact created a strategic triangle between India-Pakistan-US because bilateral Indo-Pakistani talks occurred with the backdrop of UN and Western pressures on India to accommodate Pakistani interests…

In both instances Nehru failed to stop China in her Tibetan venture and by 1956 her decision to build the Aksai Chin road through Ladakh was convincing proof that strategic calculations in the Tibet and Xinjiang frontier region were the foundation of Chinese policies, and these were related as well to Chinese fear of Soviet activities in the Xinjiang region and later in the 1950s there was fear that Nehru had tilted towards the ‘Anglo-American imperialists’ in checking China desire for security. Clearly China did not desire to be the field of international power politics after 1949 as it had been the object of British and Russian activities in Central Asia and it sought instead to be a player in the promotion of the Central Asian and Himalayan region as the object of China-led and inspired regional power politics.

The third rapid change that adversely affected Indian interests was the development of the military pact between Pakistan and USA in 1953.

Washington justified this pact as a response to the danger of spread of communism in the region and to insure that Pakistan stayed on the American side and to reject a policy of neutralism, this was deemed to be against the American interest and it was a point of objection by Washington of Nehru’s policy of non-alignment. Pakistan was glad to align its policy with the West to acquire modern arms and diplomatic support so as to balance India’s power (real or potential) by bandwaggoning with the West, and to be seen as a moderate Muslim country which could help Western interests along with Iran and Turkey in the Middle East. The US-Pakistan military pact created a wedge between American anti-communism and Nehru’s drive to build links with the communist world, and it drew a wedge between Nehru’s non-aligned policy and the Western belief that India ought to be on the American side in the global struggle between communism and democracy. This Pact also consolidated the dominant position of the Pakistani military in domestic politics; it quashed the movement within Pakistani politics to develop democratic and civilian political institutions and to move towards a neutral stance in the Cold War struggle.

Pakistan was glad to align its policy with the West to acquire modern arms and diplomatic support so as to balance India’s power…

These rapid changes in India’s strategic environment in the early 1950s had two important messages. First, that the strategic initiative to alter the South Asian environment lay in foreign hands: Pakistan, China and USA. Having insisted on the Partition, to form a Muslim homeland, Jinnah altered the military balance on India’s western and northern front by militarissing and internationalising the Kashmir region; and Nehru’s reference of the Kashmir dispute to the UN reinforced its internationalisation. China’s takeover of Tibet removed the historical position of Tibet as the northern buffer between China and then British India and now between China and India.

The US-Pakistan military pact created a strategic triangle between India-Pakistan-US because bilateral Indo-Pakistani talks occurred with the backdrop of UN and Western pressures on India to accommodate Pakistani interests for the sake of regional security and bilateral peace. The second message was that the foreign players conducted their diplomacy and their military policy according to their views of their national interests and also with a view to align themselves strategically with like-minded countries.

These rapid changes showed that precisely when Nehru’s diplomacy had lustre on the world stage – in international conference diplomacy in the Korean and Indo-China conflicts and in international peacekeeping, and in third world politics – where his message was to seek harmony and peaceful accommodation of international conflicts, India’s footprint was shrinking in her immediate strategic neighbourhood.

…the external events were beyond Nehru’s control but the Indian responses were in his control and in hindsight they showed a lack of diplomatic and military preparation.

Nehru made some moves to buttress India’s position with the Himalayan kingdoms, and he made some military preparations in the border areas, he registered his disapproval of the US-Pakistan military pact and its consequences for regional and Indian security, and he was concerned about China’s approach to Tibetan affairs, but beyond these specific objections there was little change in the diplomatic posture. He struck to his ‘peaceful co-existence with China and the world’ narrative, and maintained his position against war with Pakistan as a tool of policy.

A pattern of extensive public declarations on world events and those which affected India, and limited policy actions, emerged. But these actions showed limited policy development and a lack of strategy – diplomatic and military – to engage the foreign powers who were pressuring Indian interests. ‘Engagement’ comes about by undertaking of actions which either attract or cause conflict that require the foreign powers’ attention. To engage is to stimulate either by persuasive encouragement or by creating a point of friction which requires the opposition to adjust its policies.

The Second World War was an extreme example of engagement because it led to the reform of the domestic politics and foreign policies of Germany and Japan and brought the two powers into a long term alignment with the West. In this case engagement was first a step to create a point of opposition and friction that was settled by warfare; the second step was to encourage change in the two countries policies that were irreversible. It appears that Nehru’s India could neither stimulate change by encouragement nor by opposition. Arguably the external events were beyond Nehru’s control but the Indian responses were in his control and in hindsight they showed a lack of diplomatic and military preparation.

The following chapters argue that even though the rapid changes in India’s environment in the early 1950s were no long possibilities or probabilities, they had occurred even though they were not foreseen by Indian practitioners. Their hopes for a new and prosperous India and a reformist world clashed with the hard rock of reality which was based on calculations of balance power and national advantage in the conduct of nations; these nations were operating according to the principles of geopolitics and national interest and not according to universal principles of social justice and world peace.

India’s military modernization required massive domestic resources whereas Pakistan had access to foreign aid from the USA, Saudi Arabia and her overseas remittances.

Moreover, these powers were acting with impunity with regard to Indian interests. As noted, Nehru’s global narrative did not change in the face of these events, but there were nonetheless incremental adjustments in Indian policies. They were meant to address the imbalances which had emerged as a result of negative foreign actions.

The first major adjustment was to align India with the USSR in relation to the issues of American military aid to Pakistan and the Kashmir dispute. Moscow’s willingness to use its vetoes to stop UNSC action against India stalled the international community and as well it created a tilt towards Moscow to balance the tilt towards Beijing. This was a major adjustment in Nehru’s approach to the foreign policies of the two major communist powers because Nehru’s public declarations revealed a mistrust of Moscow and Stalin in the early 1950s and an admiration of the Chinese people and their struggle against Western imperialism. As well, as noted earlier, Nehru believed in the idea of Asian unity and an Asiatic federation which had its foundation in China-India cultural and diplomatic unity. Although Nehru admired the Bolshevik revolution as a seminal event in world history and believed in the principles of socialism, and Indian leftists who were aligned with Nehru’s party and supported his foreign policy drew their inspiration from the Soviet and Eastern European communists, Nehru did not articulated the idea of Indo-Soviet unity except in practical diplomatic and military terms.

The development of a shift in attitude from negative to positive in the Nehru-Stalin era stalemated the ill-effects of the Nehru-Mountbatten approach to Pakistan and Kashmir affairs in the diplomatic and the military spheres but they did not rollback the policy paradigm laid out by the two. With a continued military stalemate in Kashmir, the diplomatic sphere became the centre of intensified pressure by Pakistan and the international community to get India to make a concession to Pakistan’s claim to Kashmir. The Moscow tilt and the incremental development of Indian military strength in the Kashmir-Pakistan fronts reinforced the stalemate but this had economic costs – to mount a military defence of Kashmir against Pakistani interventions.

Diplomatic and military stalemate became the norm in India’s diplomatic and military behaviour which nonetheless shrunk India’s strategic footprint in the region…

India’s military modernization required massive domestic resources whereas Pakistan had access to foreign aid from the USA, Saudi Arabia and her overseas remittances. It had diplomatic costs – to maintain Indian advocacy over her rightful position in Kashmir with third world and Muslim countries and here Indian practitioners were at best able to secure Arab neutrality on the Kashmir question. The stalemate between India and Pakistan over Kashmir had diplomatic costs with the West because their sympathies lay with the Pakistani claims on Kashmir and it required continuous effort by Indian practitioners to maintain the policy against third party mediation and intervention in a bilateral dispute.

The stalemate had domestic political costs as well because the India’s political elite was not convinced about the future of Kashmir under Indian rule and there were repeated debates within India about Kashmir’s future. Here the hardness of India’s public diplomacy on Kashmir contrasted with a softness in internal debates on the subject. Finally, the differences between China’s policy towards Tibet and its implications for the boundary question and the road building in Aksai Chin, and Nehru’s public stance about the importance of peaceful relations with China and the historical basis of Indian border claims, indicated a conflict and a stalemate in the making in India-China diplomatic and military relations. Here the first part of the 1950s appears to be the process by China to consolidate its frontier position; the second part was to bring out the controversy over the boundary alignment; and third part was to use war to try to settle the controversy.

Note that following the 1962 war the pattern of Chinese and Indian conduct was to settle for a diplomatic and a military stalemate because even though Chinese forces defeated the Indian military, the campaign was limited in scope, and in the absence of Indian acceptance of defeat, the ceasefire is a stalemate between the two. Diplomatic and military stalemate became the norm in India’s diplomatic and military behaviour which nonetheless shrunk India’s strategic footprint in the region because it made the Subcontinent a field of power politics for foreign powers and reduced India’s diplomatic and military manoeuverability and it raised the costs of maintaining her territorial defence and advancing her position in the world of powers.

Nehru lacked the military experience or the inclination to deal with the invasion of Kashmir in 1947-48 and India’s policy was hijacked by Lord Mountbatten…

I turn now to a discussion of the reasons why Nehru’s India acted the way it did in the area of diplomacy and military policy. The general philosophy, attitudes and experience with British colonialism has been noted in our previous discussion. Now I turn to specifics relating to Pakistan, China and the USA. One explanation is that Nehru and his peers – e.g. V.B. Patel lacked the administrative experience to deal with the aftermath of Partition and the future of relations with Pakistan.

Another explanation is that Nehru lacked the military experience or the inclination to deal with the invasion of Kashmir in 1947-48 and India’s policy was hijacked by Lord Mountbatten, India’s first Governor General and chair of India’s Defence Committee, and a military and diplomatic strategist. On China the explanation is that Nehru had two assumptions in his mind about the Chinese leadership and he did not make up his mind about these assumptions until the war in 1962 settled his inner (in Nehru’s mind) debate. In his conversations with Canada’s High Commissioner to India, Nehru on the one hand thought that China’s leaders were rational but on the other hand thought of Indians as inferior.

There was a debate of sorts within the Indian government that involved Nehru, his director of the IB, the MEA and the Army but this was not really an institutionalized debate but rather reflected the instincts and imperfect information and views of the various practitioners. The government debate (1950s-1962) did not resolve Nehru’s assumptions about the likely basis and pattern of China’s diplomatic and military conduct towards India on the boundary question and in the world of power politics and the hierarchy of powers.

Notes

- Escott Reid, Envoy to Nehru (Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1981), p. 248.

all that could have been negated had pol ldrs at the time had not given orders to halt ops at Uri , not taken the issue to UNO and had not agreed about plebiscite. People of J&K were fully with India then.They were helping the Indian Army in ops against the infiltrators .

It’s a story of ifs and buts. If this had happened then that would have happened. If Hyderabad , juna gadh ruler opinion has no value wat is the value of Hari singh’s opinion

Even today why are we hesitating to get back POK.

Whose permission we need? france,usa, russia, Israel are asking us?

Either we don’t accept partition or if accepted partition then let Muslim majority area go to Pak. That is also a view

We have 4th largely military in world, when are we going to use, to protect our Nation territories.

Even Aksai chin is with China.

But that military has a shortage of 12000 officers. Best soldiers with no young leadership to lead. Garv sey kaho ham…….. . Jinehey naaz hai hind par wo kahan hain

With both countries being nuclear state we can’t fight also. Wat a situation

Why we allowed Pakistan to became Nuclear state? We would have destroyed Kahuta long back in 80s.

But poor and weak heart leadership but Champion in doing scams and looting Nations.

At least No first use of nuclear weapons need to review now atleast against China and Pak.

Defence ministry should allow direct entey for young officers or promote from Army who completed 10 yrs of service.

Every college should intake 50 officers we can fill gap easily.

Atleast kick out 3cr Bangladeshi who stays here illegally.

Allow 3 cr hindus to stay in Bangladesh.

Or Demand one Third land from Bangladesh.

Last 5000 yrs people have been coming and settling here . It is human tendency and may be right for every human to move to an area which offers him better life. Like u can’t stop punjabis to go to Canada / America probably it is difficult to stop Bengalis ,. Nepalese and Bhutanese are officially allowed to come here and work. Nepal/Bhutan were not part of India . Bangladesh was part of India. May be giving work permits with no voting rights , no citizenship is a solution. If u can send them back nothing like it