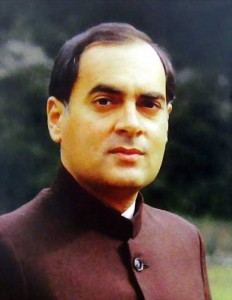

During the little over five years he was the Prime Minister, Rajiv Gandhi had three chiefs of the R&AW. G.C.Saxena, an IPS officer of the UP cadre,who had taken over as the chief in April, 1983 when Indira Gandhi was the Prime Minister, continued till his superannuation in March 1986. S.E.Joshi, an IPS officer of the Maharashtra cadre, who succeeded him, retired in June 1987, after having served as the chief for 15 months. Rajiv Gandhi was keen that he should continue so that he had a tenure of three years like his predecessor, but Joshi felt it would be unfair to his successor.

During the little over five years he was the Prime Minister, Rajiv Gandhi had three chiefs of the R&AW. G.C.Saxena, an IPS officer of the UP cadre,who had taken over as the chief in April, 1983 when Indira Gandhi was the Prime Minister, continued till his superannuation in March 1986. S.E.Joshi, an IPS officer of the Maharashtra cadre, who succeeded him, retired in June 1987, after having served as the chief for 15 months. Rajiv Gandhi was keen that he should continue so that he had a tenure of three years like his predecessor, but Joshi felt it would be unfair to his successor.

An officer of the Tamil Nadu cadre was to succeed him, but Rajiv Gandhi reportedly got annoyed with him because he was unaware of the Bofors scandal when it broke out in the Swedish electronic media. He had him shifted as the Chairman of the Joint Intelligence Committee and designated A.K.Verma, an IPS officer of the Madhya Pradesh cadre, as the chief. He had a full tenure of three years—-partly under Rajiv Gandhi and partly under V.P.Singh.Saxena, like Kao and Suntook, was suave in his behaviour and gentle in his words, but hard-hitting in action. Joshi and Verma were more like Sankaran Nair—anything but suave, blunt in words and hard-hitting in action. Like Sankaran Nair, Saxena, Joshi and Verma were experts on Pakistan and political and militant Islam. Saxena, Joshi and Verma knew more about Pakistan than any other expert in India or abroad. Saxena had never served in the Islamic world, but he had been dealing with Pakistan right from the day he joined the R&AW shortly after its formation. He did not have much to do with Pakistan only during his posting in Rangoon in the 1970s. Joshi was the only chief of the R&AW to have served in Pakistan. Verma had served in Kabul and Ankara and had been dealing with Pakistan and the Islamic world during most of his postings in the headquarters.Sankaran Nair and Verma were held in awe and respect in Pakistan’s intelligence and policy-making communities.They knew of the active role played by Nair under Kao in the liberation of Bangladesh and of Verma’s reputation as a mirror image of Nair—-as an officer who would like nothing better than to break Pakistan again if he was given the go-ahead by India’s political leadership. During my posting in Geneva and subsequently in headquarters, I had much to do with Pakistan and with various sections of the Pakistani civil society and Government.

An officer of the Tamil Nadu cadre was to succeed him, but Rajiv Gandhi reportedly got annoyed with him because he was unaware of the Bofors scandal when it broke out in the Swedish electronic media.

I could see for myself that those, who had an opportunity of interacting with Verma, looked upon him as one of the very few Indians who had a really good understanding of the Pakistani psyche and of the Pakistani military mind-set. I have no doubt in my mind that if Rajiv Gandhi had not lost the elections in 1989 and if Verma had continued as the chief of the R&AW under Rajiv Gandhi for two or three years more, Pakistan would not be existing in its present form today and innocent civilians in our country would not be dying like rats at the hands of jihadi terrorists.

There was a strong convergence of views between Rajiv Gandhi and Verma that unless Pakistan was made to pay a heavy price for its use of terrorism against India, India would never be free of this problem. The process of re-activating the R&AW’s covert action capability, which had remained in a state of neglect under Morarji Desai, started after Indira Gandhi returned to power in 1980. Suntook, Saxena and Joshi played an active role in carrying forward this process, but it was Verma, who gave the R&AW once again the strong teeth, which it was missing since 1977, and made it bite again.

Well-deserved tributes have been paid to the Punjab Police under K.P.S.Gill, the IB under M.K.Narayanan, the National Security Guards under Ved Marwah, the other central para-military forces and the Army for their role in restoring normalcy in Punjab. But, the Indian public and the political leadership as a whole barring the Prime Minister of the day hardly knew of the stealth role played by Saxena, Joshi and Verma in making our counter-terrorism success in Punjab possible. While Saxena and Joshi laid the foundation for an active and strong liaison network and for improving the R&AW’s capability for the collection of terrorism-related HUMINT, Verma gave the R&AW the teeth which made Pakistan realize that its sponsorship of terrorism would not be cost-free.

All the three of them were fortunate in having Rajiv Gandhi as their Prime Minister. Rajiv Gandhi came to office as the Prime Minister with very little knowledge of the intelligence profession and of the Indian intelligence community. When Indira Gandhi was the Prime Minister, Rajiv Gandhi used to take an active interest in the physical security arrangements for her after Operation Blue Star. She used him often in her attempts to find a political solution to the problem in Punjab. Many of his clandestine meetings in this connection were organized by the R&AW when Saxena was the chief. Beyond that, he had very little interaction with the R&AW and very little knowledge of it before he became the Prime Minster.

Rajiv Gandhi came to office as the Prime Minister with very little knowledge of the intelligence profession and of the Indian intelligence community.

It used to be said that after he took over as the Prime Minister, he was amazed—–even somewhat disturbed—– when Saxena briefed him at a one-to-one meeting on the sensitive on-going operations and covert actions of the R&AW. It was also said that while he did not have the least hesitation in approving the continuance of all the R&AW operations relating to Pakistan, China and Bangladesh, he was somewhat confused in his mind regarding the wisdom of the operational policies followed under his mother in relation to Sri Lanka . He took some time to make up his mind on Sri Lanka. Ultimately, he decided to continue on the lines laid down by his mother in relation to Sri Lanka too.

It would be incorrect to characterize his operational policy towards Pakistan as a carbon copy of the policy followed by Indira Gandhi. There were nuances, which differed from those of his mother. Indira Gandhi came to office with a strong dislike and distrust of Gen.Zia-ul-Haq, which continued till her death. She was convinced in her mind that Zia was not a genuine person and that his expression of warmth and bonhomie towards Indians was contrived. And the fact that Zia and Morarji Desai got along comfortably with each other prejudiced her mind against him.

Rajiv Gandhi did not inherit his mother’s anti-Zia prejudices. He was fully aware of the role played by the ISI in supporting terrorism in Punjab. The suspicion that the ISI under Zia might have been behind the assassination of Indira Gandhi by her security guards was never proved, but it kept haunting the minds of some persons (including me) during the 1980s. Despite this, Rajiv was prepared to consider meaningful ideas for a co-operative relationship with Pakistan. His ready acceptance of the offer of the then Crown Prince Hassan of Jordan to arrange a dialogue between the chiefs of the ISI and the R&AW to which a reference had been made in an earlier chapter was a typical example of his open mind to such initiatives.

At the same time, Rajiv Gandhi was convinced—as strongly as his mother was—- that India’s preoccupation had to be not with individual Pakistani leaders, who are a passing phenomena, but with the Pakistani mindset, which was an enduring phenomenon right rom the day Pakistan was born in 1947. In India, there is no such thing as an enduring Indian mindset towards Pakistan. The mindsets keep changing with leaders and circumstances. It is not so in Pakistan.

The compulsive urge to keep India weak, bleeding and destabilized influences policy-making in Pakistan— whoever be the leader, civilian or military. It has nothing to do with its humiliation in Bangladesh in 1971. It was there before 1971 and it has been there since 1971. Some leaders such as those of the fundamentalist parties openly exhibit it, but others manage to conceal it behind seeming warmth in their behaviour. Till that mindset changes, India has to adopt a mix of incentives and disincentives in its operational policies towards Pakistan—incentives towards a co-operative relationship and disincentives to discourage hostile actions.On the need for a mix of incentives and disincentives, Rajiv Gandhi, Saxena, Joshi and Verma were on the same wavelength. Rajiv Gandhi’s ready acceptance of Crown Prince Hassan’s offer was an example of such an incentive. It was fully backed by the R&AW without any mental reservations, though it did not ultimately produce the desired results. As examples of disincentives, one could mention the timely and effective pre-emption of Pakistani designs to use the Siachen glacier to weaken the Indian position in the Kargil and Ladakh areas and the use of the R&AW’s covert action capability to make Pakistan realize that it would have to pay a heavy price for its use of terrorism against India in Punjab.Another component of the operational policy followed under Rajiv Gandhi was to frustrate Pakistan’s goal of a strategic depth in Afghanistan.

The policy of frustrating Pakistan’s goal in Afghanistan was actually initiated under Indira Gandhi by Kao immediately after the formation of the R&AW in 1968. Strong relationships at various levels—-open as well as clandestine— were established not only with the people and the rulers of Afghanistan, but also with the Pashtuns of Pakistan. India’s desire for close relations were readily reciprocated by the Afghan people and rulers and by large sections of the Pashtun leadership. The networks established in the 1970s continued to function even after the occupation of Afghanistan by the Soviet troops and the installation in power of a succession of pro-Soviet regimes in Kabul.

When Indira Gandhi was the Prime Minister, Rajiv Gandhi used to take an active interest in the physical security arrangements for her after Operation Blue Star. She used him often in her attempts to find a political solution to the problem in Punjab.

The Soviet Union blessed and welcomed this networking and helped it grow in strength in whatever way it could. This networking created misunderstanding in India’s relations with the Afghan Mujahideen leaders. They were hurt and disappointed by India’s reluctance to support their struggle against the Soviet occupation, but these feelings of hurt and disappointment did not turn them hostile to India. Many Afghan Mujahideen leaders—Pashtun as well as Tajik— maintained secret contacts with the R&AW even while co-operating with the ISI and the CIA against the Soviet troops in Afghanistan. Rajiv Gandhi fully supported this policy.

Thus, Saxena, Joshi and Verma under Rajiv Gandhi’s leadership followed a triangular strategy towards Pakistan—-co-operative relations where possible, hard-hitting covert actions where necessary and close networking with Afghanistan.

This policy started paying dividens in Punjab even when Rajiv Gandhi was the Prime Minister in the form of reduced ISI support for the Khalistanis, but this did not prevent the ISI from interfering in a big way in J&K from 1989. The successors of Rajiv Gandhi as the Prime Minister had the good sense to realize that this was an argument not for discontinuing Rajiv Gandhi’s policy, but for further strengthening it. This triangular strategy was continued with varying intensity under the successors to Rajiv Gandhi, but, unfortunately, Inder Gujral, who was the Prime Minister in 1997, discontinued it under his Gujral Doctrine. He ordered the R&AW to wind up its covert action division as an act of unilateral gesture towards Pakistan. His hopes that this gesture would be reciprocated by Pakistan were belied. His policy towards Pakistan became one of unilateral incentives with no disincentives.

If I recall B RAMAN who was from the MP Cadre is no more. He passed away a few years ago. Why are you referring to him in the ‘Present’ tense.

THIS WAS ALSO THE PERIOD WHEN ISI TRIED TO CAUSE MUTINY IN RAW WHEREIN THEY RECRUITED A LOW LEVEL FUNCTIONARY, ONE RK YADAV. HE WAS FINALLY DISMISSED FROM SERVICE ALONG WITH OTHERS. THAT IS WHY THIS CHARACTER CONTINUES TO SPIT VENOM AGAINST RAMAN