A Grand Army Humiliated

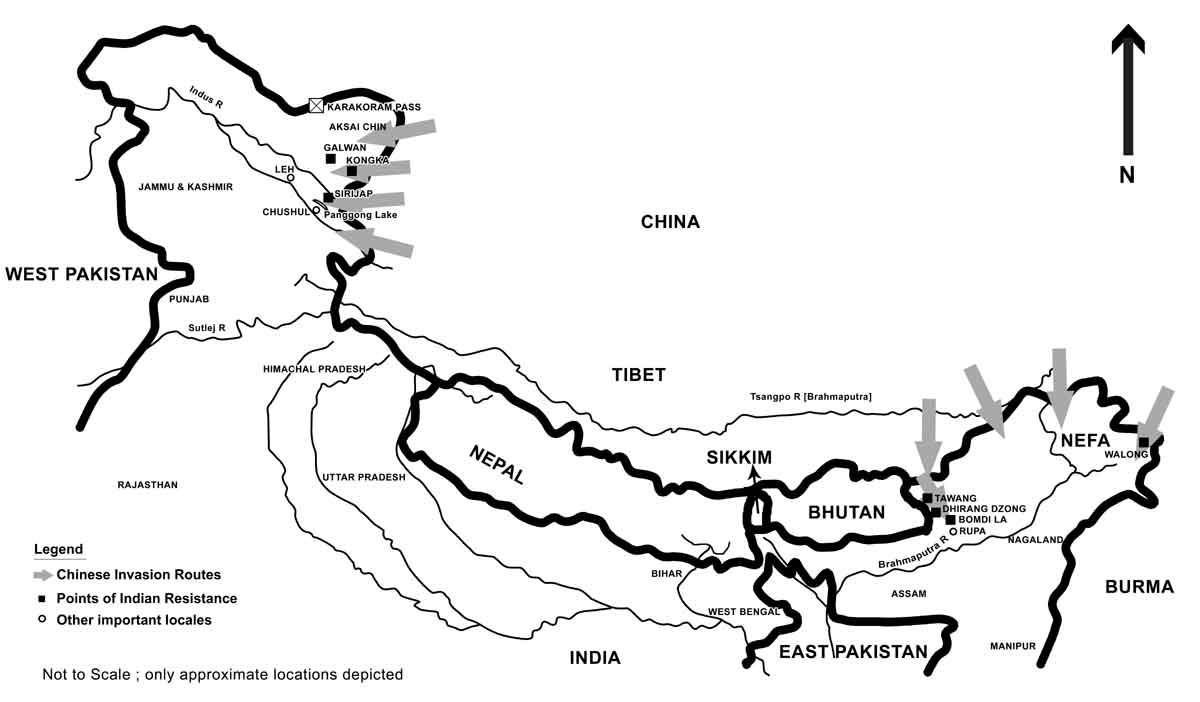

It was an uncalled for war forced on an unprepared army by a national leadership which couldn’t have been more naive. Having provoked a powerful neighbour into open aggression by its unrealistic foreign policy, the Government of India perpetrated the unpardonable sin of committing the troops for an operation for which they were least prepared and wholly ill equipped, blatantly ignoring the counsel1 of its field commanders. The result was a catastrophe of unprecedented magnitude. The Indian Army, always exalted for its glorious victories in the field, was to be meted out a drubbing it would find hard to live down. Pummelled to withdraw from its positions on the border, it would end up ceding chunks of own territory to the enemy, as the Chinese unleashed a massive offensive in October 1962.

The Indian Army, always exalted for its glorious victories in the field, was to be meted out a drubbing it would find hard to live down.

In the unholy debacle, the Madras troops bore its share of humiliation along with the rest of the great army. Two battalions of the Madras Regiment, 1 and 2, were deployed in the North East Frontier Agency (NEFA), the theatre which was to witness a virtual rout of the Indian side. 1 Madras, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel K K Chandran, was one of the units which took the brunt of the onslaught. It had been rushed up from the planes of Assam where it was concentrated, to take up defences at Bomdi La at a height of 13,000 feet from the sea level, to stem the tide of invasion after the Chinese had overrun the Namka Chu Valley of the Kameng Frontier Division. Arriving at the location on 27 October, they joined 48 Infantry Brigade which formed part of 4 Infantry Division defending the heights. The battalion dug in with the rest of the brigade, and even as it was engaged in forward patrolling, the enemy was busy perfecting his approach road to Bomdi La.

The attack came on the morning of 18 November. D Company, commanded by Major Harbans Singh, which had moved to nearby Dirong Dzong to protect the Divisional Headquarters located there, was the first to come under attack. Confronted by a two-battalion force of the enemy, they held out tenaciously, men fighting from slit trenches with no artillery or mortars for support, while the Divisional Headquarters withdrew itself safely to Rupa in the rear. Outnumbered and outgunned, the company put up a desperate fight, making the enemy pay with heavy casualties; but past noon, with its position no more sustainable, it fell back in order to the battalion location at Bomdi La, where the entire brigade was reeling under intense shelling since the morning. At 1645 hours an enemy force of almost two divisions launched an attack on the two forward battalions of the brigade defences, 1 Sikh Light Infantry on the left and 1 Madras on the right. While the Sikh LI was withdrawn later that day, the Madrassis held on putting up a grim fight, until isolated and short of ammunition, they were forced to pull out by early hours of the following day.

They made it to Tenga Valley by 21 November, but found themselves cut off by the Chinese holding positions to their rear. As the battalion tried to extricate itself towards Charduar, it was ambushed. Major WNC Hensman, the Second-in-Command, leading the column, was killed along with seven of his men in the Intelligence Section, and 13 others were wounded. The CO with 3 other officers, 5 JCOs, 187 Other Ranks and 2 non-combatants were taken prisoner. Among the officer prisoners was Captain EN Iyengar, the Regimental Medical Officer of the battalion, who continued to attend to the casualties at great peril to his life. He was to be awarded the Vir Chakra on his release.

The war had ended for them even without the satisfaction of at least having fully engaged the enemy once.

The rest of the battalion made it to Charduar in small groups in the days that followed, some of the groups having had to make a detour of more than 60 miles. The entire operation was a chaotic affair characterized by the disastrous breakdown of command and control at the formation levels, leaving individual units to fend for themselves. It saw men with no acclimatization fighting at high altitudes without snow clothing or footwear, bereft of even up to date maps, not to mention the vintage bolt action 0.303 rifles they carried against the modern automatics the enemy had; and it cost the units dearly. A severely wounded pride apart (for a unit that had fought so gallantly in J&K in 1947-48), 1 Madras had suffered some 300 casualties; 8 killed, 13 wounded, 37 missing believed dead, and 216 captured.

2 Madras, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel PT Allen, also under 4 Infantry Division, was deployed at Tuting. Although the enemy attacks on the outposts were beaten back by the battalion (losing a JCO in one of the attacks), in a typical goof up at the formation level, the Divisional HQ ordered the abandoning of Tuting on 19 November before any major attack materialized. The battalion pulled out in the early hours of the 20th, and after a torturous three-week-long march arrived at Along on 9 December. The war had ended for them even without the satisfaction of at least having fully engaged the enemy once.

15 and 65 Field Companies of the Madras Sappers, who had been engaged for engineering support at Bomdi La and Walong in NEFA, got caught up in the fiasco and had to share the miserable fate with the rest of the troops. However in the west along the Ladakh front, where the army generally succeeded in putting up a comparatively better show, the Madras Sappers made an eminent bit of contribution with engineering support to the troops under fire. When the Chinese attacked the Sirijap Posts along the northern shores of Panggong Lake to the north of Chushul on 21 October, the Sappers of 9 Field Company fought alongside the Gorkhas who put up a last-ditch battle, and were taken prisoner when the posts were overrun. Meanwhile two entire detachments of 372 Field Company, one at Galwan and the other at Kongka, were wiped out.

A sad and shameful commentary on a proud nation and its army, that for that moment in history, we found ourselves at the enemy’s mercy.

In the hurried withdrawal across the lake that followed, 36 Field Company ferried the troops across at night on two storm boats. One of them sank hit by enemy fire. Naik Raghavan, a hundred yards ahead in the other boat, turned around without a moment’s hesitation to rescue the survivors from the sunken boat. He managed to save three of the infantrymen, before a fast Chinese tug came at him with headlamps on. The NCO’s death-defying courage was to earn him a Vir Chakra. The next day two Sappers of 9 Field were killed by enemy fire while laying mines in the area.

9 Field Company, commanded by Major SR Bagga, took up the hectic preparations for the defence of Chushul by 114 Infantry Brigade, while 372 Field Company helped prepare the airfield there. The ceasefire came into effect as the brigade had withdrawn to the defence sector west of the airfield, following the enemy bombardment of Chushul.

There were some more Madras troops – a couple of battalions of the Madras Regiment – which were also mobilized, but saw no action. 16 Madras was airlifted from Madras and concentrated near Gangtok, and 17 Madras was moved to Misamari foothills, but before either of them contacted the enemy the war ended with the Chinese declaring unilateral ceasefire on 21 November. And India let out a sigh of relief; it had been a close call – the gate to the planes of Assam, albeit briefly, had fallen open to a foreign invader. A sad and shameful commentary on a proud nation and its army, that for that moment in history, we found ourselves at the enemy’s mercy.

Notes.

- The Chinese had always disputed the validity of the McMahon Line as the international boundary. A pragmatic approach would have been to resolve the matter through diplomatic channels, since the Indian Army didn’t really have the wherewithal at that time to get into a contest with the Chinese while containing an inherently hostile Pakistan as well. However the Government of India, incensed by the aggressive posturing China adopted following the strained relations on the Tibetan issue, ordered the army to occupy posts to the north of the McMahon Line, on a one-sided interpretation that the water-shed beyond the line was inclusive in it. These posts, besides violating the line as depicted on the map, were tactically untenable – enough provocation, as well as tempting objectives, for the Chinese to attack. The commanders in the field did point out this folly, but the army’s higher command proved too meek to prevail upon the political leadership.

Don’t forget the 1967 bloody nose given to Chinese. Indian Army is very capable and 1962 was a Nehruvian blunder and not the fault of Indian Army.

The army put up a show of courage and valour under impossible conditions They could have done none the better under the conditions. Political leadership was scared of building armed strength for the fear of a coup and was openly contemptuous of men in arms. Even today, the Henderson Brooks report is secret. and Neville Maxwell’s India’s China War still is banned. I wish the report were released and the book brought out for sale in India, so that future generations may learn from history and not repeat the mistakes made by arrogant political leadership of the day, which was ignorant of warfare.

An eye opener from a brave solider to the future and present generations, that what awaits us in the future if China is not shackled with the liberation of Tibet either through an open war or a proxy one.

Tibet will be liberated and it will become an independent Nation one day

What really hurts is that the political leadership has had no key learnings from the debacle. No public debate post war, no declassifying key documents for public scrutiny etc. One could console one’s self about the gross humiliation that defeat at war yields generally for the people and particularly for the Jawans frontlining, if only one learns and vows never to repeat the same mistakes.

The precious lives of Indian Jawans and sacred territory cannot be at the mercy of uneducated, medieval leadership which after all has a reputation of dividing people and systematically killing the spirit of nationalism. Pity things have been allowed to degenerate. for a country the size,spirit and intellect of India, by now, we should have occupied global leadership position with ease. But Im getting tired of saying this while the reality is the exact opposite.