Hubs, Routes and Rates: Most of the consignments used to originate in Thailand, which received arms from China and Cambodia. Ships with arms would reach Cox Bazar and other regions of Chittagong, which were then taken to different destinations in the Northeast. Sonamura in Tripura, Jayantia and Garo Hills in Meghalaya and Dhubri in Assam were the favoured entry points for supply to NSCN-IM, ULFA, Bodo and Manipuri rebels. But two incidents in 1995–1996—Operation Golden Bird by the Indian army in Mizoram and a mysterious blast in a ship carrying weapons—shifted the focus to the overland and riverine routes through Myanmar as safer and less time-consuming. Added to this was the tough posture against militants and gunrunners by the army-backed regime that assumed power in Dhaka in 2006 and the current Awami League–led government that ruptured the earlier congenial ambience for these activities in Bangladesh.

It is a common refrain among Indian army and police officials that NSCN and Kuki militants often go to Myanmar empty handed and return laden with arms.

In late 2009, NSCN-IM’s intelligence chief Anthony Shimray procured weapons from Yunnan, which he wanted to transport through Bangladesh, but the directorate general of forces intelligence (DGFI) refused permission. Subsequently, the consignment had to be taken to the Buthidaung jetty on the banks of the Mayu river in Myanmar and thence to different locations.22

Deals are struck at Ruili in Yunnan, but another town Tengchong has emerged in the same province in China where consignments are released to be sent across Myanmar to select spots along the Indo-Myanmar border.23 These two routes branch off into different directions in Myanmar, with even the Irrawady and Chindwin rivers now being used profusely for faster passage. A senior NSCN-Khaplang (NSCN-K) cadre said his chairman S. S. Khaplang derives a regular income by taxing boats that ferry arms through the Chindwin. Consignments are offloaded and arms stacked at some points (like Tamu) till orders are received from the Northeast. Phek in Nagaland, Chandel and Churachanpur in Manipur and Champai in Mizoram are the entry points to other destinations in the region.

It is a common refrain among Indian army and police officials that NSCN and Kuki militants often go to Myanmar empty handed and return laden with arms. If caught, they simply say that the weapons are from the designated ceasefire camps and usually no case is made out against them. There have also been several cases when NSCN cadres have sold arms and ammunition to Dimasa militants, sometimes by stealing from the armoury at Camp Hebron near Dimapur.24 Individual agents also sometimes make direct purchase from these villages and sell it elsewhere. On 25 July 2009, two Naga youths, Akam Konyak and Tinkam Konyak, were arrested at Namtola in Sivasagar district of Assam after they were caught trying to sell a pistol to a customer.

“¦small quantities may be off loaded at Jirikinding in Karbi Anglong district of Assam to be taken to other destinations

Routes inside India keep on changing, and they pass through National Highways, forests, hilly terrain and towns. The heavy deployment of security forces along the Moreh-Imphal-Kohima-Dimapur highway has increased the importance of the other road, which originates at Champhai in Mizoram and passes through Silchar, Ladrymbai, 8 Mile, Umrangsho, Jirikinding, Panimur Waterfalls (after crossing Kopili River) and N C Hills. At times, small quantities may be off loaded at Jirikinding in Karbi Anglong district of Assam to be taken to other destinations. Agents are found at selected towns and villages along the way or nearby areas who would place the order either at Moreh or Dimapur, the biggest hotspots in the Northeast for purchase of arms. In NC Hills, a well-known arms dealer Nambui Dumgbe was shot dead by Black Widow militants at Tumje on 17 March 2009 since he had sold weapons to a rival faction.

The network is sustained by a delicate understanding among militant groups, agents and, sometimes, government officials. Quite often, a group might ask for a part of the consignment as fees for taking them from one point to another and allowing passage through the territories they dominate. The UNLF colluded with the Myanmarese Chin National Front (CNF) to procure weapons from different destinations, and two major deliveries were received in 1996 and 1998.25

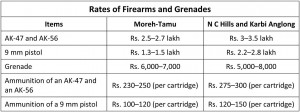

The price goes higher as the consignments travels deeper into the Northeast. For instance, an AK-47 assault rifle costs between Rs. 2.5 and 2.7 lakh in Moreh–Tamu, which could go up to around Rs. 3 lakh and even higher sometimes by the time it reaches N C Hills. Among all items, the rates at which 9 mm pistols are sold have been found to fluctuate; an original Chinese-made is as expensive as Rs. 2 lakh and as less as Rs. 20,000 for assembled pieces, and this cheap variety is sold in pockets in some villages from NC Hills to Changlang, in Arunachal Pradesh.26

Alongside pistols, there are reports of assault rifles being assembled in Manipur at Moreh and Saikul. These are made of parts that come from Myanmar and local manufacturers. An AK-47 produced in these centres ranges between Rs. 1.5–1.7 lakh and would sometimes be sold off as Chinese made. Dimasa and Kuki militants who have used them said their quality was inferior as the barrel gets heated up fast and there’s problem with the magazine as well. But their demand seems to be picking up, with more and more gangs emerging in the region who have a stake in the different types of transnational crimes.

Stemming The Flow

The proliferation and misuse of small arms and grenades are vexing problems that call for a multilayered approach and coordination for prevention. India has broached the issue of proliferation many a time with Beijing, but the situation has only deteriorated, with the illegal trade indicating an increase in volume over the last few years. However, what has been encouraging for India was a statement by the Chinese representative to the UN, Li Baodong, on 20 March 2010 that his country was opposed to the illicit production and proliferation of small arms.

| Editor’s Pick |

Li, who was speaking with reference to the Central African region, pointed out that China was willing to work together with the international community towards an “early and appropriate” solution to the problem. “Each state should, on the basis of the UN Program of Action on Small Arms and in connection with its specific situation, formulate a complete set of rules and regulations on the production, possession, transfer and stockpile of small arms and ensure their effective enforcement,” he said at an open debate of the Security Council and added that countries of the region (read Central Africa) should strengthen coordination and cooperation to monitor the trade in small arms and combat illicit transactions.27

The marking of small arms is, to some extent, covered by the UN Firearms Protocol, but there is no single system for marking or tracing small arms.

Li’s statement is a heartening departure since China, along with countries like the U.S. and Russia, has always been opposed to certain measures long advocated by NGOs and think tanks across the globe that could have made a dent in the scale of the unlawful trade. Laws like legally binding international treaties on arms brokering, development of transparency mechanisms for small arms exports and imports and expansion of assistance programs to states seeking more effective implementation are being contested by countries due to the apprehension that such initiatives would encroach on their national practices and limit their future freedom of action.

In particular, NGOs have made a case for marking and tracing of weapons since it is extremely difficult to ascertain where they originated, which countries they travelled through and where they were being used. If the origin and transfer routes of weapons can be identified, it would be much easier to work out how and when they got into the hands of unintended users and identify those responsible for supplying and diverting the arms. The marking of small arms is, to some extent, covered by the UN Firearms Protocol, but there is no single system for marking or tracing small arms. A few NGOs led by the Groupe de Recherche et Convention on Marking, Registration and Tracing have developed a draft convention that addresses some of these concerns.28

The debate on proliferation has also focused on limiting the impact of weapons currently in circulation, which would perhaps hold true for the situation at Yunnan, in China, and Myanmar. When surplus weapons remain in a country, they can easily find their way to the black market. For example, a Ukrainian parliamentary commission estimated that when the country achieved independence in 1992, its military stocks were worth $89 billion.

India is already investing in infrastructure in Myanmar, the policy could well be expanded to include Sagaing and Kachin, which are adjacent to the Northeast and have a direct bearing on small arms proliferation

Over the next decade, thousands of these weapons were stolen and resold abroad, including to governments and insurgent groups in several war zones.29 Therefore, government weapons stockpiles must be effectively managed and secured. Disarmament, demobilisation and reintegration (DDR) programs often help to reduce the illicit trafficking and misuse of weapons in the hands of ex-combatants and armed gangs. In the Northeast, militant groups that have signed accords and ceasefire agreements with the government have never surrendered their entire arsenal but have either sold them to other groups or stacked them for future use.30

The situation in South and Southeast Asia being somewhat different from other war zones, India could make efforts to develop a consensus at SAARC and ASEAN and initiate dialogue with countries of the region affected by small arms. The objective should be to identify deficiencies in national control policies and bring about remedial measures within a stipulated timeframe. China must be pressed to change policies to ensure firm control over ordnance factories and weapons issued to the military and police. Equally important for the Northeast is the situation in and role of the dictatorial regime in Myanmar.

With reports pouring in about the establishment of an arms manufacturing factory by the Wa militants, proliferation would still continue even if the supply routes are choked from China. With Myanmar dictator General Than Shwe cosying up to India, New Delhi must seize the opportunity to drive home the point that curbing transnational crimes like gunrunning would stand to benefit both countries in the long run. Of course the fact remains that unless poverty is reduced in Myanmar and a final settlement is reached with militant outfits (like KIA or UWSA), a change in government policy may not have the desired result.

There is an urgent need to expand the definition of small arms to include grenades. Small arms proliferation is not confined to the Northeast but is reaching mainland India as well.

Since India is already investing in infrastructure in Myanmar, the policy could well be expanded to include Sagaing and Kachin, which are adjacent to the Northeast and have a direct bearing on small arms proliferation. These twin regions are the least developed in Myanmar, with deplorable social and economic infrastructure, which explains the involvement of the local populace in transnational criminal activities. Besides opening up vistas of employment, development of Kachin and Sagaing would also be in sync with India’s Look East Policy to reach out to and establish a bridge with Southeast Asia.

In fact, Nagaland chief minister Neiphiu Rio has already taken up the issue with the centre and has made a case for New Delhi’s active involvement in “Eastern Nagaland” (Sagaing), which he described as a “No Man’s Land.” Investments apart, New Delhi must also consider fencing the Indo-Myanmar border on the lines of Indo-Bangla frontier to curb the illegal trades. A review of the free border regime, which allows free movement of people on both sides of the Indo-Myanmar border, must be reviewed and restrictions imposed in the vulnerable zones.

An appropriate number of battalions of the Assam Rifles must be earmarked specifically for border policing, which may necessitate raising additional manpower. Local communities on both sides of the border must be made aware about gunrunning and its concomitant effects and the assistance of credible NGOs taken wherever essential. Above all, the development of border areas must be taken up on a war footing so that alienation is curbed and employment avenues are opened up. To a considerable extent, increase in gunrunning in the Northeast is the direct fallout of decades of negligence of the frontier regions.

Conclusion

In sum, China is the primary origin of arms and grenades that are released and distributed through a network highly systematic and discreet, with little evidence to pinpoint Beijing’s role. Myanmar, Bangladesh and Thailand, to an extent, are the routes for small arms. A wide cross-section of people in these countries and the Northeast, including government officials, militants and the mafia, benefits from the small arms proliferation, which seems to have grown in volume in the last decade. New Delhi must have a comprehensive and holistic policy on small arms.

| Also read: |

Moreover, there is an urgent need to expand the definition of small arms to include grenades. Small arms proliferation is not confined to the Northeast but is reaching mainland India as well. But security forces and agencies have not been able to comprehend the gravity of the problem, and this is the reason for the lack of awareness about its dangerous implications. Furthermore, little effort has been made so far for a serious dialogue on the issue with neighbouring countries. Therefore, the possibility of a decrease in the inflow of small arms and grenades looks remote in the near future.

Notes and References

- Adopted by United Nations General Assembly on 8 December 2005 and included in the International Instrument to enable states to identify and trace, in a timely and reliable manner, illicit small arms and light weapons.

- Application filed by the author under the Right to Information Act with Assam Police on 25 June 2009.

- Pradeep Phanjoubam’s remark in the seminar on small arms proliferation held at Omeo Kumar Das Institute for Social Change and Development, Guwahati, on 18 June 2009.

- Mandy Turner and Bina Lakshmi Nepram. “The Impact of Armed Violence in North East India: A Mini Case Study for the Armed Violence and Poverty Initiative.” Centre for International Cooperation and Security. November 2004.

- Ibid.

- Interview with a director in the MHA on 3 January 2008.

- Small arms survey by Graduate Institute of International Studies. Geneva. 2006.

- These letters of the alphabet were seen on some AK-56 rifles with UPDS cadres at Rongbin in Karbi Anglong and with UKLF cadres at Sinai in Chandel.

- Subir Bhaumik. Troubled Periphery; Crisis of India’s North East. Sage Publications, 2009.

- Interview with ULFA militants and intelligence officials in 2004 after Operation All Clear in Bhutan in December 2003.

- Interview with Mrinal Hazarika (former commandant of ULFA’s 28th Battalion) on 2 November 2008 and Lengbat Ingleng (defence secretary of UPDS) on 31 January 2008.

- PLA commander-in-chief Manohar Mayum spoke about the alliance with naxalites to journalists in one of their camps on the Indo-Myanmar Border near Ukhrul in Manipur on 4 May 2009.

- Interview with a joint secretary in the Research & the Analysis Wing (R&AW) on 5 December 2007.

- Subir Bhaumik. “Guns, Drugs & Rebels.” 29 June 2005. <http://www.india-seminar.com/2005/550/550%20subir%20bhaumik.htm> (accessed 18 September 2010).

- Times Now. “Serial Blasts Rock Assam.” 30 October 2008.

- Anthony Davis. “Law & Disorder: A Growing Torrent of Guns and Narcotics Overwhelms China. Asiaweek, 25 August 1995.

- Liana Sun Wyler. “Transnational Crime in Burma.” CRS Report for Congress. 29 July 2008.

- Tom Kramer. “The United Wa State Party: Narco-Army or Ethnic Nationalist Party?” Policy Studies 38. East-West Center, 2007.

- Reported in the Sentinel, 24 June 2008. A detailed discussion on the drug trade and production is also given by Bertil Lintner and Michael Black. Merchants of Madness: The Methamphetamine Explosion in the Golden Triangle. Silkworm Press, 2009.

- Op cit, n. 16.

- Interview with Mrinal Hazarika (former commandant of ULFA’s 28th Battalion) on 2 November 2008, Surya Rangfor (publicity secretary of UPDS) on 30 January 2007 and James Bond Kuki (publicity secretary of UKLF) on 19 September 2007.

- Times of India. “NSCN Gun-Runners a Threat to Talks.” 26 May 2010.

- Telegraph (Northeast Edition). “Arms Flow Feed Militancy.” 29 October 2004. Both Tengchong and Ruili in Yunnan are named as centres where arms are released.

- Interview with Dima Halam Daogah chairman Dilip Nunisa on 2 April 2008.

- Sagolsem Hemant. Far Beyond in the Misty Hills.

- Indian Express. “China Emerging as Main Source of Arms to NE Rebels: Jane’s Review.” 22 May 2009. According to the report, the price of an AK-56 assault rifle in the Northeast ranges between Rs. 2.5 and 3 lakh and that of an M20 Chinese Pistol Rs. 1.5 lakh.

- Reported by China Daily, which quotes a report by Xinhua. 9 August 2010.

- Rachel Stohl, Matt Schroeder and Dan Smith. The Small Arms Trade; A Beginner’s Guide. Oneworld Publications, 2006.

- Ibid.

- K. Warikoo. Himalayan Frontiers of India: Historical, Geopolitical and Strategic Perspectives. According to the author, the Mizo National Front (MNF) sold weapons in Bangladesh and Northeast after surrendering in 1986.