The illicit proliferation and misuse of small arms is among the most pressing security threats that have affected a large number of countries. Thousands of people are killed or wounded every year in conflicts that are fought primarily with these weapons. Proliferation has gradually increased in the Indian subcontinent, fuelled by a host of factors, including the spread of low-intensity conflicts.

Indias Northeast is one of the most affected zones since the maximum number of insurgent outfits are found in this region”¦

India’s Northeast is one of the most affected zones since the maximum number of insurgent outfits are found in this region, which is in addition to a variety of transnational criminal activities that have increased the demand for small arms. More demand for small arms is matched by an equally prompt supply from different sources supported by an intricate web of relations and agreements that cut across regions, communities and countries. The failure of governments to come together and chalk out coordinated efforts in the region has also contributed to this problem.

Ambiguity shrouds the definition of “small arms.” The closest the United Nations has come to an official definition is contained in an agreement reached in 2005 that defined small arms and light weapons as any “man-portable lethal weapon that expels or launches, or designed to expel or launch, or may be readily converted to expel or launch a shot, bullet or projectile by the action of an explosive.” It adds that a small arm is a weapon designed for individual use, such as inter alia, revolvers and self-loading pistols, rifles and carbines, submachine guns, assault rifles and light machine guns.

The failure of governments to come together and chalk out coordinated efforts in the region has also contributed to this problem.

Light weapons are designed for use by two or three persons serving as a crew although some may be carried and used by a single person. They include heavy machine guns, hand-held underbarrel and mounted grenade launchers, portable anti-aircraft guns, portable anti-tank guns, recoilless rifles, portable launchers of anti-tank missile and rocket systems, portable launchers of anti-aircraft missile systems and mortars of a calibre less than 100 millimetres.1

According to another definition, any firearm that can be fired manually and whose calibre is below 12.67 mm is called a small arm. India’s Northeast and the adjoining areas have witnessed proliferation of not only small arms but grenades as well, which are in fact more easily available. The supply of Chinese arms through Bangladesh has become somewhat irregular since 2006 (which is also why the Myanmar routes have become more active) after the military-backed regime assumed power in Dhaka. But grenades continue to be supplied from districts in Bangladesh bordering Dhubri and Garo Hills and according to some sources, indigenous manufacture has also started at locations on both sides of the border.

Development funds have been increased to all the seven states, but embezzlement continues and scams are dug out at regular intervals.

As such, a discussion on proliferation would be incomplete without including a discussion of grenades, which in fact have been used more frequently than small arms in attacks by militants in the Northeast. The two items are inseparable as both are ferried by the same agents along the same routes and released from the same destinations, barring a few exceptions.

The Problem

New Delhi’s so-called multipronged approach to tackling insurgency in the Northeast, which is intricately related to the increasing demand for small arms, suffers from fundamental flaws. For one, not all movements in the region are imbued with a separatist hue but are essentially the outcome of unemployment and alienation. The outfits in Assam’s hill districts and those from the Kuki-Chin-Mizo communities in Manipur and Mizoram are glaring examples. A majority of them have already come over ground through ceasefire agreements with the government.

| Editor’s Pick |

So, unemployment should have been tackled on a war footing, development projects completed in a time-bound manner and greater transparency ensured at all levels of administration. Development funds have been increased to all the seven states, but embezzlement continues and scams are dug out at regular intervals. On 30 May 2009, Mohit Hojai, the chief executive member of North Cachar Hills in Assam, was arrested along with a joint director, R. H. Khan for misappropriation of development funds and giving a share to militants. (This case, incidentally, has been handed over to the National Investigation Agency for investigation)

But who are the actual players in this illicit trade? Is Beijing involved, or is it solely criminal gangs that have targeted the Northeast as a lucrative destination?

Likewise, there has been no attempt to comprehend the problem of small arms proliferation in the region. So, there has been no sustained effort to work for a solution. The problem indeed is very serious if existing facts are taken into account—firearms are sold at hubs across Assam, Manipur, Nagaland, Arunachal Pradesh and Meghalaya, and one needs to have only the right contacts to buy sophisticated assault rifles and grenades. And a good majority of all arms consignments originate in China, which are distributed across the entire region through a well-organised network sustained mainly by the military-militant-mafia nexus.

But who are the actual players in this illicit trade? Is Beijing involved, or is it solely criminal gangs that have targeted the Northeast as a lucrative destination? Why are Chinese firearms more easily available now compared to the situation a decade ago? And what is the quantity of such firearms available in the region?

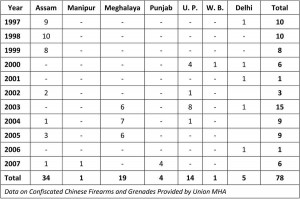

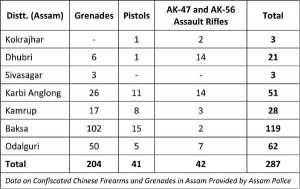

The government’s awareness of and attitude to the problem is best revealed by the contradictions in the responses received from the Union and Assam governments on confiscation of Chinese arms and grenades over a period of 10 years (1997–2007). An application filed by the author under the Right to Information Act with the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) said that a total of 34 items were seized in Assam during the 10-year period, which included 20 pistols but no grenades. Data given by the state government says that 204 grenades, 41 pistols and 42 assault rifles (AK-47 and AK-56) were confiscated in seven districts alone during the same period!2 A senior journalist from Manipur also cast serious doubts on the figures given on Manipur by MHA.3 The same pattern would undoubtedly emerge if data is gathered from the rest of the Northeastern states.

Chinese Firearms and Grenades Seized from 1997 to 2007

There are an estimated 75 million firearms in South Asia, 63 million of which are in unauthorised hands4. The Northeast has become a market for illegal arms ever since the Naga National Council (NNC) raised the banner of revolt in the mid-1950s. From a few rifles given by China in the late 1960s to the NNC, the sources expanded over the years and they have been traced to Pakistan, the U.S., UK, Czechoslovakia, Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Cambodia, Myanmar and Israel.5 During the last decade or so, the supply of Chinese-made firearms has far exceeded the supply of firearms made in other countries. This aspect is proved from the seizures made and from the interrogation of gunrunners and militants.But there is no evidence to suggest that the Chinese government is directly involved in the illicit trade. Firearms and grenades are released in such a manner that discerning the official stamp is difficult. A senior official in the MHA said, “We have asked the Ministry of External Affairs several times to take it up with Beijing but they have time and again told us to provide hard evidence which is next to impossible. So we have stopped bothering ourselves. Ultimately MEA has a role to play in checking the menace and it can’t simply put the blame on us.”6 Not only that, intelligence agencies drew flak when they were asked by the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO) to submit details in 2008.

There are an estimated 75 million firearms in South Asia, 63 million of which are in unauthorised hands4. The Northeast has become a market for illegal arms ever since the Naga National Council (NNC) raised the banner of revolt in the mid-1950s. From a few rifles given by China in the late 1960s to the NNC, the sources expanded over the years and they have been traced to Pakistan, the U.S., UK, Czechoslovakia, Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Cambodia, Myanmar and Israel.5 During the last decade or so, the supply of Chinese-made firearms has far exceeded the supply of firearms made in other countries. This aspect is proved from the seizures made and from the interrogation of gunrunners and militants.But there is no evidence to suggest that the Chinese government is directly involved in the illicit trade. Firearms and grenades are released in such a manner that discerning the official stamp is difficult. A senior official in the MHA said, “We have asked the Ministry of External Affairs several times to take it up with Beijing but they have time and again told us to provide hard evidence which is next to impossible. So we have stopped bothering ourselves. Ultimately MEA has a role to play in checking the menace and it can’t simply put the blame on us.”6 Not only that, intelligence agencies drew flak when they were asked by the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO) to submit details in 2008.

There is no production of firearms by private agencies in China, and the state-owned Norinco is among the top five manufacturers in the world in rifles, submachine guns, machine guns and grenade launchers (the others are Heckler & Koch in Germany, Izhmash in Russia, Colt in the United States and F N Herstel in Belgium). According to available data and estimates, the Russian Federation, the United States, Italy, Germany, Brazil and China exported more than US$100 million worth of small arms and light weapons in 2003.7 Not surprisingly, it is not only India’s Northeast that has been flooded with Chinese firearms; the Taliban are using them and the Peoples’ Liberation Army (PLA) of Nepal also had access to sources in China.

A few assault rifles even have two letters of the Chinese alphabet marked on them meaning “Lian Dan”””an automatic rifle or something that can shoot continuously.

Most militant outfits are ignorant about the nuances of the trade barring some in Manipur and Nagaland but many are aware that consignments mostly originate in China. The author saw a few M-16 rifles in Manipur with the United Kuki Liberation Front (UKLF), Kuki Liberation Army (KLA) and PLA, but the bulk was undeniably the Chinese-made Kalashnikov assault rifle and the 9 mm pistol. A few assault rifles even have two letters of the Chinese alphabet marked on them meaning “Lian Dan”—an automatic rifle or something that can shoot continuously.8 It is difficult to imagine that assault rifles produced in a country other than China would have these letters. However, since 2007, occasional reports suggest that the United Wa State Army (UWSA) has established a large weapons manufacturing facility in Myanmar on franchise from some Chinese ordnance factories.9

Similar to the Chittagong Arms Haul incident of 2 April 2004 in Bangladesh, but lesser in scale, was another episode that occurred in the icy heights of the Sino-Bhutan frontier in 1997. Information reached Indian intelligence agencies that a consignment was waiting to be transported from China to camps in southern Bhutan, belonging to United Liberation Front of Asom (ULFA), National Democratic Front of Bodoland (NDFB) and Kamatapur Liberation Organisation (KLO). Thimpu was alerted, and not only was the entire operation foiled but three officials of the Bhutanese army who colluded with the rebels for ferrying the weapons were arrested and put behind bars.10

“¦it is not only Indias Northeast that has been flooded with Chinese firearms; the Taliban are using them and the Peoples Liberation Army (PLA) of Nepal also had access to sources in China.

Senior leaders belonging to United Peoples’ Democratic Solidarity (UPDS) and ULFA’s 28th Battalion (A & C Companies) have stated that around 70–80% of their armoury of assault rifles, pistols, cartridges, grenades and grenade launchers are of Chinese origin.11 It is not without reason that the Communist Party of India-Maoist (CPI-M) active in central India has firmed up an alliance with Manipur’s PLA last year.12 With the left-wing insurgency drawing to a close in Nepal and LTTE’s base demolished in Sri Lanka, a viable option for the supply of firearms could be from China through the Northeast. PLA is one of the outfits believed to have a presence in Yunnan and some pockets along the Sino-Myanmar border.

The demand has increased over the years, and arms will continue to pour into the Northeast since there’s no sanction of any sort on any of the seller countries. Unlike other weapons, no international control system governs small arms and grenades. During the Cold War, nuclear, biological and chemical weapons dominated international policy agendas and arms control efforts. Until the early 1990s, if countries were interested in the control of conventional weapons, it was predominantly heavy weapons that received attention. The UN Register of Conventional Arms—a voluntary mechanism for sharing information on imports, exports and procurement of some weapons systems—and the Wassenaar Arrangement, whose goal is to promote greater responsibility in conventional arms and dual-use exports, focus primarily on heavy conventional weapons. Small arms were often left out of these initiatives.

All that the UN has been able to achieve so far are a set of three international instruments: the politically binding Programme of Action that was adopted in July 2001; the legally binding Protocol Against the Illicit Manufacturing of and Trafficking in Firearms, Their Parts and Components and Ammunition, which entered into force on 3 July 2005; and the politically binding International Instrument to Enable States to Identify and Trace, in a Timely and Reliable Manner, Illicit Small Arms and Light Weapons, adopted by the General Assembly in December 2005. These protocols are limited in scope and content and set standards for national systems in such areas as firearms manufacture, marking and transfer.

Causes of Proliferation

A combination of several factors has made the Northeast and the adjacent regions ideal for transnational criminal activities like gunrunning and drug trafficking. They are fuelled by a distinct set of push and pull factors that range from the policies followed by Chinese ordnance factories to the volatile situation in Myanmar, Bangladesh and the Northeast.

“¦it may seem in a country ruled by an iron fist, the situation in some areas of Yunnan is not very different from that in Indias Northeast or some of Myanmars in so far as law and order is concerned.

President Deng Xiaoping, the architect of China’s vibrant economy today, had directed the military to generate its own resources, and the PLA (of China) had reportedly even ran nightclubs for self-sustenance.13 Over a period of time, Norinco, the state-run ordnance factory, began selling arms to buyers from different countries, which explains the wide availability of Chinese firearms in all troubled spots in Central and South Asia. It was also in the late 1990s that some Mafia groups (like Blackhouse) in Yunnan began supplying these firearms from ordnance factories to Northeast rebels.14 The biggest advantage of this source was that firearms were much cheaper than Thailand’s and supply through the land routes in Myanmar more consistent and safer than through the sea routes.

Easy availability led some outfits like the PLA and ULFA to station their own agents permanently in a few Chinese towns close to Kachin in Myanmar. After Operation All Clear in Bhutan in 2003, the ULFA despatched a small team under SS Lieutenant Partha Gogoi to establish a liaison office near Putao on the Sino-Myanmar border. The ULFA chief of staff, Paresh Barua, visited this office and even held a meeting with Burmese and Chinese army officials in late 2005. Subsequently, the ULFA supremo slipped into Yunnan in China and stayed there for a few months, which was exposed by a TV news channel on the day of the serial blasts in Assam on 30 October 2008 and later confirmed by former director general of Assam Police, G. M. Srivastava.15

Surprising as it may seem in a country ruled by an iron fist, the situation in some areas of Yunnan is not very different from that in India’s Northeast or some of Myanmar’s in so far as law and order is concerned. Describing the state of affairs in the province in 1995, a leading Asian magazine said, “Last year seizures of illegal arms were up nearly 30% over 1993. That reflected both increasing availability of guns and rising official alarm. In September, a month long crackdown netted some 120,000 illegal weapons. And while military handguns are the hottest item, gun-running syndicates are also marketing grenades and sub-machine guns. In May (1995), Guangdong police seized anti-tank rocket launchers.” It goes on to explain how firearms once sold to Vietnamese and Burmese communists by Beijing were finding their way back to Yunnan and landing in the hands of organised crime syndicates.16

Like the Wa troops, many Northeast militant groups have also taken to gunrunning and protection of the drug trade albeit on a lesser scale.

The task of these crime syndicates has been rendered easier by the existing conditions in Bangladesh and Myanmar that facilitated a military-militant-mafia nexus and easy availability of porters and agents due to unemployment and poverty. In Bangladesh though, Pakistan’s ISI was an important factor and its role has been reconfirmed from the new investigation into the Chittagong Arms Haul of 2 April 2004. Two senior officials from National Security Intelligence (Bangladesh’s equivalent of Intelligence Bureau) have also been arrested, and the interrogation of a local gunrunner Hafizur Rehman has revealed that ULFA’s Paresh Barua and the intelligence chief of National Socialist Council of Nagaland-Isak Muivah (NSCN-IM) Anthony Shimray were present when the consignment came in from the Sittwe Port in Myanmar by sea. This consignment too was sourced from Yunnan, and many Northeast outfits and the CPI-M had a stake in it.

In Myanmar, the lure of easy money has drawn a section of Myanmar army officials into drug trafficking and other illicit trades.17 At least 2 of the 20-odd insurgent outfits—Kachin Independence Army (KIA) and UWSA—that arrived at ceasefire agreements with the Myanmar Junta have forged links with Yunnan and the mafia to get a share in the arms trade. Incidentally, all these insurgent groups have been allowed by the government to carry on all kinds of activities in their respective territories. A ban on opium cultivation has been imposed in Kokang and Wa regions in Myanmar, but that has had the unintended consequence of enhancing poverty and forcing people into gunrunning and production of synthetic drugs as a means of alternate livelihood.

| Editor’s Pick |

UWSA deserves a special mention as it is both the largest ethnic and narco-ethnic army in the region, with a cadre strength of more than 20,000 troops.18 Wa soldiers formed the bulk of the Communist Party of Burma (CPB) till they revolted and decided to float the present organisation in 1989. Today, it has monopolised the entire trade on amphetamine (a synthetic drug, ATS), and some of its leaders, like the Wei brothers, are among the biggest drug barons in Myanmar. The U.S. has indicted as many as eight senior Wa leaders on drug-trafficking charges, including Bao You Chang, chairman of United Wa State Party, the political front of UWSA.

Since extortion from businessmen and government officials does not amount to much in the hill states, extra income from other sources is needed to pay allowances and salaries to cadres.

UWSA cadres have been spotted at Tamu across Moreh in Manipur, and there has since been an increasing inflow of “yaba” (ATS variant) into Manipur. They have firmed up deals with Naga and Kuki rebels and are also the main suppliers of weapons in a huge stretch along the Chandel-Churchanpur belt.19 Chinese officials have welcomed Wa investment in Yunnan; the Golden Phoenix Hotel in Simao is proudly described in a brochure as a joint venture between “the Wa Federation of Myanmar [Burma]” and Yunnan’s Provincial Farming Bureau.20

Like the Wa troops, many Northeast militant groups have also taken to gunrunning and protection of the drug trade albeit on a lesser scale. Both the Isak-Muivah and Khaplang factions of NSCN, United National Liberation Front (UNLF), PLA, Prepak, Kanglei Yawol Kanna Lup (KYKL), Zomi Revolutionary Organisation (ZRA) and Kuki National Army (KNA) are among some groups that are involved, and they tax all drugs and arms consignments passing through their areas.

Since extortion from businessmen and government officials does not amount to much in the hill states, extra income from other sources is needed to pay allowances and salaries to cadres. Interestingly, the annual expenses of many outfits have gone up after they signed ceasefire agreements with the centre.21 Most of these groups have recruited more cadres after coming over ground in violation of the ceasefire ground rules, and unemployed young adults and children are always easily available in the region due to rampant unemployment, socioeconomic deprivation and a host of other factors.

Continued…: Small Arms Proliferation in the Northeast: The Chinese Connection – II