[Tawang is a name that burst into our national consciousness in October 1962 as India’s China War began at the Thagla Ridge. Before that hardly anyone had heard of this small monastery town in a remote part of the Himalaya.

But though the mass of the Indian people had never heard of it, Tawang had become quite famous in it’s own special way among diplomats in London and Delhi, Simla and Lhasa and even Beijing long before 1962. Around this obscure place fitfully rotated a political vortex whose end we may not have seen even now.

This is the story of Tawang before 1962, and of the men who made it a part of India.]

Defeat in the First Anglo-Burmese War led to Burma ceding Assam and other territories to the British by the Treaty of Yandabo (1826). This brought the British Indian Empire right up to the foothills of a huge stretch of forested hills which rose North to the Assam Himalaya and the Tibetan plateau. These hills were inhabited by numerous tribes, many warlike, and not part of any country. Tibetan tax-gatherers occasionally made their way down river-valleys to collect what they could from some of the tribes, but otherwise made no attempt to provide an administration. There was one significant exception : at the Eastern end, abutting Bhutan, was a well-settled area under Tibetan administration – the Tawang Tract.

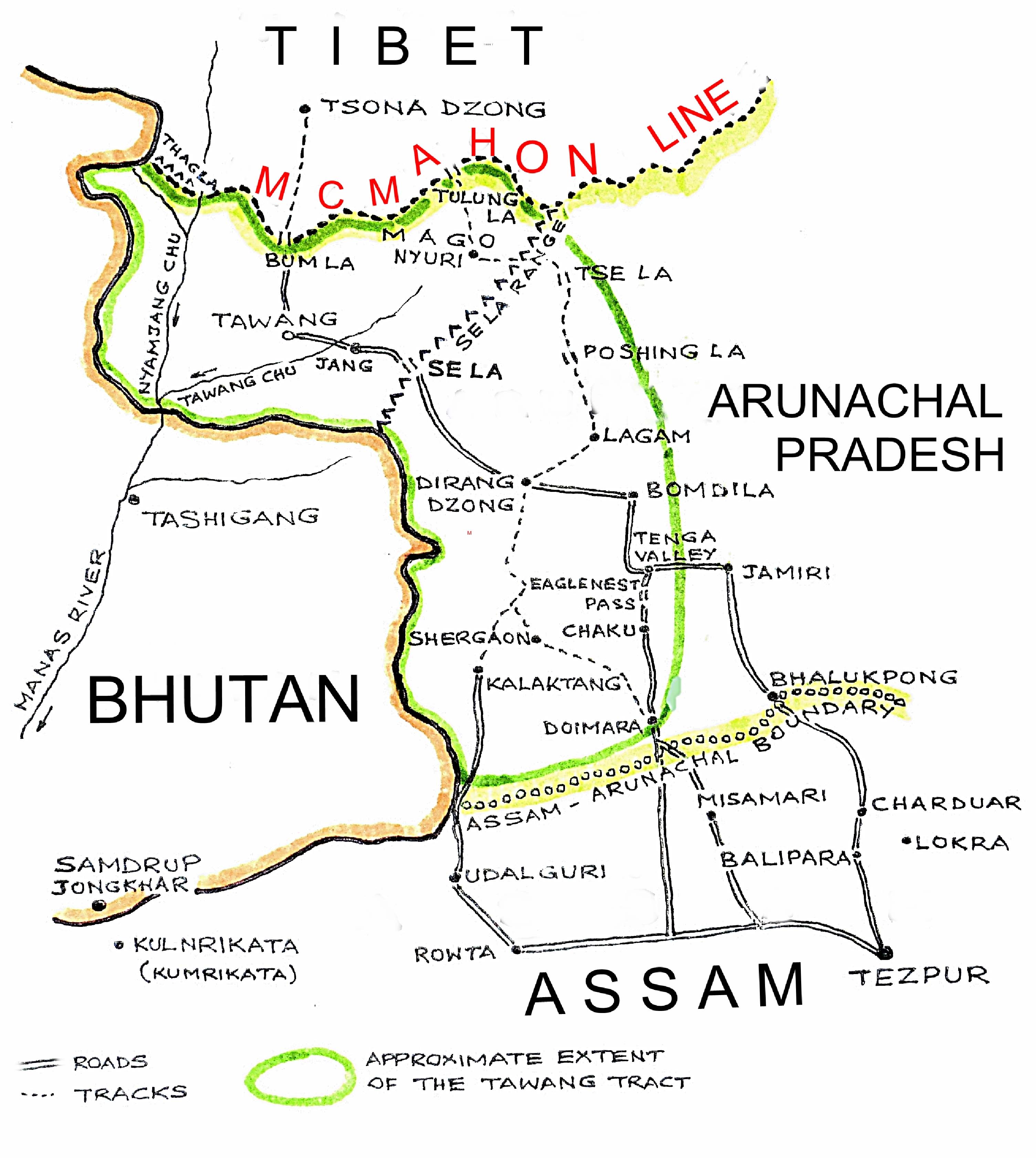

The Tawang Tract lay in the present-day districts of Tawang and West Kameng, and measured some 5000 sq. km. The Se La Range running SE from the main Himalayan axis divided the tract in two. The Northern part was administered by two Dzongpons (District Commissioners) based at the Tibetan town of Tsona Dzong in summer and Tawang in winter. The Southern part, beyond the Se La pass (c.4170 metres), was under the control of the Tawang Monastery, a subsidiary of the Drepung Monastery, one of the greatest and most influential in Tibet. Jongpens appointed by Tawang Monastery administered it from Dirang Dzong and Kalakteng. The revenues went to Tawang Monastery and thence to Drepung.

In the beginning the British were quite content to have the border of Assam run along the foothills touching the Tawang Tract, which provided comparatively easy access from Tibet to the Assam plains. To facilitate trade movement Lt. Rutherford set up a market at Udalguri in 1833, and the frontier between British territory and the Tawang Tract was amicably settled in 1872-73. But imperial paranoia about Russia and Tibetan incursions into Sikkim and other irritants caused a decline in Anglo-Tibetan relations that ultimately led to the Younghusband mission marching to Lhasa in 1904 and the signing of an Anglo-Tibetan treaty. This was not liked by China’s Manchu Dynasty, then in terminal decline, as China was nominally Tibet’s ‘suzerain’, a nebulous concept that meant different things to different people.

The Chinese attempt to strengthen their grip over Eastern Tibet in 1904 led to a Tibetan uprising in 1905, which was easily crushed by Chinese forces led by General Chao Erh-feng. Chao proceeded to bring restive Tibetan districts to heel in a slow but methodical campaign which culminated in his entering Lhasa in 1910. It was during this expansionist campaign that Chinese patrols put up flags and boundary stones in the Lohit Valley at Menilkrai, a little South of Walong, in 1910 and 1912: these were mostly removed in 1914 by T.P.M. O’Callaghan, Asst Supdt of Police and later Asst Political Officer, Sadiya, an expert on the Lohit valley. However, Ronald Kaulback saw one boundary stone in 1933.

This display of military muscle by the Chinese alarmed the British. Suddenly a major power had displaced the pacific Tibetans, and the Tawang Tract had been transformed from a minor trade route to a possible invasion route into the heart of the Assam plains.

To counter this threat the Chief of the Imperial General Staff consigned diplomatic niceties to the devil and proposed the Indo-Tibetan border should be pushed up from the foothills to a line running North of Tsona Dzong. Apprehensions about Chinese resurgence were mitigated by the murder of Gen. Chao Erh-fang in December 1911 and the overthrow of the Manchu Dynasty by the Republicans in January 1912. Taking heart at the sudden decline of China, the Tibetans besieged Chao’s troops in Lhasa. These troops were eventually repatriated to China through Calcutta. The hostile relationship between China and Tibet presented an opportunity which was effectively exploited by Britain to convene a Tripartite Conference between Tibet, China and Britain that began work in October 1913 in Simla.

To supplement the diplomatic initiative, the British also undertook a number of expeditions to chastise troublesome hill tribes like Abors and Mishmis which had surveying as one of their main objective, and also encouraged explorers like F.M.Bailey, H.T. Morshead and others to travel in Southern Tibet and make maps and route surveys.

The Tawang Area

In the course of their extraordinary journey to find the Tsangpo Falls in 1913, Bailey and Morshead carried out a detailed plane-table survey of the area of Tibet just North of the main Himalayan range, and finished it up by mapping much of the Tawang Tract. They crossed the Tulung La pass (now on the Indo-Tibetan border) to Mago, and then crossed the Tse La and Poshing La to reach Dirang Dzong by a well-known route that nevertheless became known as the ‘Bailey Trail’ as if it was discovered by Bailey (talk about Imperial hubris!). From Dirang they crossed Se La and travelled through Jang and Tawang to Tsona Dzong and beyond, then followed the Nyamjang Chu valley to Tashigang in Bhutan, and reached the Assam Plains at Kumrikata. As they relaxed in Calcutta in November 1913 Bailey received a telegram:

Delighted to hear of your safe return hope you are well I would like you to come up to Simla as quickly as possible.

– McMahon foreign

Sir Henry McMahon, Secretary to the Indian Foreign Department, was the driving force behind the Simla Conference, whose main aim was to settle the Sino-Tibetan and Indo-Tibetan frontiers. He needed Bailey and Morshead’s maps and inputs and O’Callaghan’s surveys to decide on the Indo-Tibetan boundary alignment. The intransigence of the Chinese caused McMahon and the Tibetan plenipotentiary Lonchen Shatra to conclude two secret Anglo-Tibetan agreements, one relating to trade and the other relating to the Indo-Tibetan boundary East of Bhutan. The latter border drawn by McMahon (the famous McMahon Line) ran East from the Bhutan frontier well North of Tawang, and then generally followed the Himalayan crestline. It thus placed the entire Tawang Tract within Indian territory. Lonchen Shatra accepted this boundary in March 1914, and it was later ratified by Lhasa.

Poor Tibet! They sacrificed Tawang, the birthplace of the Sixth Dalai Lama, in the hope that Britain would be able to persuade China to agree to a Sino-Tibetan frontier that would be acceptable to Tibet. But the Simla Convention ended in failure when the Chinese Government repudiated Ivan Chen’s initialling of the Tripartite Treaty. The British Government desultorily tried to convince China, but failed. As Tibet’s suzerain, China also refused to acknowledge Tibet’s right to accept the McMahon Line boundary without Chinese approval, although Tibet was by then de facto independent. Therein lies the root of the 1962 conflict.

No attempt was made to extend Imperial administration to these newly-acquired territories, doubtless because they possessed no valuable resources that would justify the effort and expense. The earlier boundary became the Inner Line, travel beyond which required a Inner Line Permit, and the areas beyond the Inner Line were divided into a number of Frontier Tracts, lightly policed but otherwise unadministered. Tawang fell in the Easternmost of the Frontier Tracts, the Balipara Frontier Tract. In 1954 these Frontier Tracts were merged to form the North East Frontier Agency, which would later become Arunachal Pradesh.

Two British officers, Capt. G.A.Nevill and Capt. R.S.Kennedy IMS, visited Tawang in March-April 1914, but with the outbreak of World War One in August 1914 British attention shifted elsewhere, and the fact that Tibet had ceded the Tawang Tract gradually vanished from memory. When Aitchison’s authoritative Treaties Vol. XIV was published in 1929, the Simla Convention was omitted as it had not been ratified by China. There was no attempt by the British to advance their control and administration to the McMahon Line boundary, and Tibet continued to administer the Tawang Tract as hitherto.

In 1935 a mission headed by F. W. Williamson, the Political Officer of Sikkim, was visiting Lhasa when it was informed that the famous botanist-explorer Francis Kingdon-Ward had been briefly arrested by Tibetan authorities for entering the Tawang Tract area North of the Se La Pass despite being denied permission to do so. Kingdon-Ward himself does not mention this incident in the account of his trip, though he does mention that he was given verbal permission to travel by one of the Tsona Dzong Dzongpens he met at Shergaon village. That he was rubbed the wrong way during this trip may perhaps be inferred from his advocacy of British occupation of Tawang in an article written in October 1938.

The Tibetan protest to the Williamson Mission against this violation of their border set off an investigation at the Foreign and Political Office of the Govt. of India to determine if Kingdon-Ward was indeed guilty of a border violation, and resulted in the discovery that the entire Tawang Tract was within Indian territory by virtue of the Simla Convention. The ensuing diplomatic exchanges led to the confirmation of the McMahon Line as the international border by Tibet without, however, any move to relinquish control of Tawang.

Under the prodding of Sir Olaf Caroe, the British attempted to retrieve the mistake of not publishing the Simla documents in Aitchison’s Treaties , and a new Vol. XIV was published in 1937 with the relevant documents and substituted for the 1929 volume : however, a few of the original 1929 volumes survived and led to the detection of this maneuver. Simultaneously steps were taken to print new maps showing the revised frontier, partly in response to Chinese maps showing the foothills as the border of Sikang Province.

In 1936 the Governor of Assam , Sir Robert Reid, argued the desirability of taking control of the areas South of the McMahon Line as continual toleration of the Tibetan presence in the Tawang Tract could in future enable China to lay claim to the area by virtue of it’s suzerainity over Tibet. The matter was broached to Tibet, who replied that the acceptance of the McMahon Line boundary by Tibet in 1914 was in the expectation of a satisfactory settlement of the Sino-Tibetan border dispute through the good offices of Britain; since the latter event had not happened, the Tibetan Govt. could not be expected to cede territory and get nothing in return. Moreover, this stand was tacitly supported by British acceptance of the Tibetan administration of Tawang for 21 years. Despite considerable moral misgivings, the British refused to accept the Tibetan quid pro quo viewpoint as it had not been explicitly stated in the Anglo-Tibetan boundary agreement, and stuck to their claim over the area ceded by Tibet.

Under Reid’s prodding, action was initiated at last in 1938. A small column led by Capt. G. S. Lightfoot reached Tawang on 30th April, with the objectives of gathering intelligence, showing the flag, and gauging the reaction of the Tibetans. Birding seems to have been a hobby of his, for he sent seven Skylark skins collected in the Tawang area in May-June 1938 to Hugh Whistler, the famous ornithologist. Clearly Whistler was not quite sure where these skins came from, for he tagged them as coming from Eastern Bhutan!

[Lightfoot, a student of Cheltenham College in 1914, served in the 101st Grenadiers during WW1,and later joined the Indian Police, serving as Political Officer, Balipara Frontier Tract in 1934-1942. After war broke out with Japan he became a Lt. Col. commanding the V Force in the Kohima area in May 1942. Later he was the Supdt. of Police of Sylhet from Dec.1945 to Dec.1946.]

[Sir Robert Niel Reid (1883-1964), KCSI KCIE was the Governor of Assam from March 1937 to May 1942,and the man whose drive and persistence overcame the nervous shilly-shallying that characterized British official policy about taking control of the ceded territories. He wrote History of the Frontier Areas of Assam (Shillong 1942), the authoritative work on the exploration and gradual absorption of Arunachal Pradesh at ground level.]

In response to incursions by Tibetan tax-collectors in the Upper Siang Valley, cold-weather posts manned by Assam Rifles were set up at Karko and Riga in 1940 and 1941. Meanwhile, London and Simla/Delhi continued to writhe ineffectually between the conflicting objectives of taking possession of the territory ceded by Tibet and not hurting Tibetan sentiment. What precipitated action at last was the ease with which Japan captured huge areas of China and threw the British out of Burma. Suddenly the British were confronted by the possibility of the Japanese appearing on the Northern horizon of Assam without any warning.

James Philip Mills, ICS served in the Naga Hills from 1917 onwards, first as SDO Mokokchung and then as Deputy Commissioner at Kohima, and became an accomplished anthropologist, publishing a number of books on Naga tribes etc. He mentored Christoph von Furer-Haimendorff, the world-famous Austrian ethnologist, and in 1942 was awarded the prestigious Rivers Memorial Medal of the Royal Anthropological Institute.

After serving as Secretary to Sir Robert Reid from 1937 to 1942, Mills became the Advisor to the Governor of Assam on Tribal areas in 1943, and was entrusted with the duty of extending Imperial control over the territories ceded by Tibet in 1914. Despite being aware of the ethnic dissimilarity between the Assamese and the Frontier Tract tribals, Mills stuck to his task. He pulled out Furer-Haimendorff from an internment camp for enemy nationals near Hyderabad, and sent him as ‘Special Officer Subansiri’ to the Itanagar area to establish British authority over the Apatanis, the Nyishis and Hill Miris. The cold-weather posts at Karko and Riga were converted to permanent Assam Rifles posts, and other posts came up at Walong (on 19th October 1944) and Dirang Dzong (also Kalaktang?). Tibetan tax collectors at Dirang were firmly told to leave. In a short period the portion of the Tawang Tract lying South of the Se La came under nominal British control.

[James Philip Mills (1890 -1960) CIE CSI MA was educated at Winchester and Oxford. He joined the ICS in 1913 and served in Assam till 1948. He was a Reader in Anthropology at the world-famous School of Oriental and African Studies in London (where Furer-Haimendorff also served) in 1948-54, and President of the Royal Anthropological Institute in 1951-53.]

However, the British refrained from taking over the Northern portion of the Tawang Tract to avoid injuring Tibetan sensibilities deeply. Also, an idea had been floated that redrawing the McMahon Line along the Se La Range would allow Tibet to hold on to the core of the Tawang area and assuage hurt sentiments at Lhasa. In the event, no decision was reached as pressing post-war problems pushed Tawang to the back burner, and once India became independent the British were free of the burden of decision-making.

Tibet refused to acknowledge India as the successor state to the British, and in late 1947 sent a message to India that failed to confirm that Lhasa would abide by existing treaties, and took a hard line in asking India to return Tibetan territories such as Sikkim and Darjeeling! Although Tibet did at last recognize independent India as the successor state to British India in June 1948, they did not resile from their territorial demands : this was deeply resented by Delhi.

In the post-war years, Tibet found the Chiang Kai-Shek government as inflexible as ever on their intention to destroy Tibetan autonomy, and their efforts to rally international support and involve the United Nations failed. All they got was an inadequate trickle of weaponry. The Chinese Civil War delayed Tibet’s doom, but by 1949 the Nationalists were beaten and fleeing to Taiwan. Lhasa’s tactic of buying time by stringing out negotiations with the Communists failed, and by now influential Tibetan officials were willing to collaborate with the Red Chinese.

On 5th October 1950 the Chinese invasion began, and the main Tibetan defences in Kham crumbled in just two weeks, partly due to treachery. Tibet was forced to capitulate, and the signing of the 17 point Agreement on 23rd May 1951 marked the end of Tibetan autonomy.

While the world were watching the unfolding tragedy of Tibet, a canny Sindhi politician, Jairamdas Daulatram(1891-1979) was carefully watching his own fief. A brilliant student and lawyer who came under Gandhiji’s spell, he was compared to pure gold by the Mahatma and remained a true Gandhian all his life. He participated in the Salt Satyagraha, served as the Mahatma’s secretary during the Boycott movement, and was shot in the thigh in 1930 while leading a Congress agitation. Appointed Governor of Bihar after Independence, he served as an Union Minister before becoming Governor of Assam in May 1950.

Jairamdas Daulatram

Jairamdas understood perfectly well that Tibet would fall, and appreciated the risk the occupation of Tawang by the Red Chinese represented to Assam and India. But he also knew his Jawharlal Nehru – a charismatic man full of high sentiments and fine speeches, but overly concerned with his international image and irresolute in the face of hard decisions. Nehru would under no circumstance authorise any act that could cause a diplomatic furore. Sardar Patel, the one man he could have turned to, was on his deathbed – he would die in December 1950, leaving behind a vacuum never to be filled. Jairamdas was on his own. He didn’t mind.

In late 1950, as the Chinese advanced in Tibet, Jairamdas summoned an Assistant Political Officer called Major Bob Khathing. The conversation went something like this:

“Do you know Tawang?”

“No, sir”, answered Bob.

“Possession of Tawang is vital to the safety of the North-East”, said Jairamdas, “and we must take it before the Chinese do. But I cannot get any troops – if I tell Delhi there will be an almighty row! I want you to study this Secret file, and then quietly go and take Tawang for India. But don’t let anyone hear about it !”

“Yes, sir” said Bob.

Who was this Bob Khathing that he should be entrusted with such a hush-hush mission?

Ralengnao Khathing was a full-blooded Tangkhul Naga, born in the Ukhrul District of Manipur in February 1912. He got his B.A. degree from Cotton College, Guwahati in 1937 and went back to Ukhrul to teach : by 1939 he was the Headmaster of Ukhrul High School. He joined the Army (service no.1577) when war broke out, and was commissioned in May 1941 in the 19th Hyderabad Regiment (which would later become the Kumaon Regiment), serving under K.S.Thimayya, the future Army Chief, at the Regimental Training Centre, Agra.

By 1942 he was in the newly raised Assam Regiment at Shillong. He acquired his popular nickname ‘Bob’ when American officers in the Officers’ Mess at Jorhat failed to pronounce ‘Ralengnao’ and decided to call him ‘Robert’, quickly abbreviated to Bob.

Padma Shri Ralengnao ‘Bob’ Khathing, MC MBE

In 1942 the British formed the ‘V Force’ on the Burma Front. It consisted of lightly-armed local levies stiffened by Assam Rifles personnel, and commanded by officers drawn mainly from police and administrative services who were familiar with the area and spoke the local language. V Force units stayed in their own ethnic area, and were tasked with acting as forward screen, intelligence-gathering and guerrilla operations. Their effectiveness varied widely.

Sent to recruit men for the V Force’s Manipur group in the Ukhrul area, Bob Khathing shed his uniform and went Tangkhul, sporting a shaven head with a thick central mane, and carrying food in a basket on his back with his gun hidden in his Tangkhul shawl. A successful recruiter, he operated in Southern Manipur and the Kabaw Valley with good effect, and can stand as the archetype of the Nagas so fulsomely praised by General William Slim in his book ‘Defeat into Victory ‘. A fine unorthodox soldier, he was twice Mentioned in Despatches, made a Member of the British Empire (MBE) in Dec.1943, received the Commander-in-Chief’s Gallantry Certificate in Feb. 1944, was promoted to Captain (temporary), and awarded the Military Cross in June 1945.

V Force Cap Badge

In 1947 the Chief Minister of the Manipur Maharaja’s government persuaded his friend Bob to resign from the Army (with the rank of Honorary Major), and join his cabinet. He served as a minister till the state joined the Indian Union in 1949.

After six months of unemployment Bob joined 2 Assam Rifles (2 AR) in 1950 as Asst.Commandant at Sadiya at the urging of Sir Akbar Hydari, Governor of Assam. He and his unit did sterling relief work in the Mishmi Hills after the devastating Assam earthquake of 1950. He then became the Asst. Political Officer in Tirap Frontier Tract, and from November 1950 was on deputation to the Abor Hills on special duty when Jairamdas summoned him.

Bob Khathing was an excellent unconventional soldier: Jairamdas the shrewd old Sindhi had picked his man well.

After studying the file Bob went back to the Governor and asked for two month’s time to do the job. Jairamdas gave him 45 days, and Rs. 25000/- as expenses.

Bob put together a column of about 200 men from 2 AR and 5 AR and selected Capt. Hem Bahadur Limbu of 5 AR and Capt. Modiero of the Army Medical Corps to accompany him. Since the troops would have to operate at high altitude in deep winter he needed a lot of winter clothing and camping gear ; he found it in the boxes of stores abandoned at the end of the war by the United States Army Air Force at the air bases of Chabua and Dinjan. Packing what he needed in the USAAF boxes, he sent these by rail to Tezpur.

At Tezpur he made arrangements for hiring 200 mules, 400 plains porters and 200 hill porters, then took his men to Lokra, c.26 kms. North of Tezpur, for intensive drilling, route marching and firing practice for three weeks. Simultaneously scouts were sent out to reconnoitre trails and gather intelligence, and porter teams despatched up the trail to make forward dumps. The column left Lokra on January 17, 1951.

All this activity attracted the attention of Major T.C. Allen, the last British political and intelligence officer in Assam, based at Dibrugarh. When Allen caught up with the column on January 19th and confronted Bob, the latter told Allen he had two choices : either join the expedition, or be kept under arrest till the objective was attained. Allen gladly joined the column as Khathing’s second-in- command.

Moving at a steady pace by way of Bhalukpong, Jamiri and Bomdila, the column reached Dirang Dzong on the 25th. It seems that the Assam Rifles post set up at Dirang Dzong in 1944 had been withdrawn at some time, and the area allowed to fall back under Tibetan control, for Katuk Lama, the ruler of Dirang, owed allegiance to Tawang rather than Guwahati. Khathing celebrated the first anniversary of Republic Day on January 26th by raising the Indian flag and inviting the locals to a burra khana, while his men fired volleys into the air and the Governor’s Dakota, sent to monitor the column’s progress, circled in the air above the town.The cowed Katuk gave in and sent runners out towards Tawang with warning messages.

After resting a few days at Dirang the column moved out on February 1, crossed Se La pass on the 3rd and reached Jang on the 4th. He sent out invitations for a feast to locals, and welcomed the headmen and elders of surrounding villages who called on him next day. Bob explained to them that they were now free citizens of India, and should stop paying homage and taxes to Lhasa. Capt. Limbu and part of the column was detached to build a defensive emplacement with a check post and barracks.

The column camped at Gyankar on the 6th, where a local Dzongpen tried vainly to bribe Bob into turning back with gold and women. It snowed and the weather turned extremely cold, but the men were comfortable in their fine American gear. Tawang was reached on 7th February 1951, and after two days a campsite was found to the North-West of the monastery and steps taken to build a permanent base.

The Dzongpen, a man called Nyertsang, did not respond to Khathing’s invitation for a meeting, so on the night of the third day (10th February) Bob fired off 20 rounds of 2-inch mortar and 1000 rounds of .303 – the thunderous reverberations from the surrounding hills sounded like ‘the voice of God’ and struck terror in the populace. Next morning the Indian tricolour was hoisted in front of the monastery and the troops marched up and down through the town for four hours with fixed bayonets. The nervous Dzongpen sent emissaries at last, and Bob set Major Allen the job of drafting a formal instrument of accession to India.

The talks made little headway, so on the 13th the Dzong officials were rounded up and brought to camp and well wined and dined for a week. After putting them in his pocket Bob firmly ordered them not to obey the Dzongpen.

By now it was the 20th of February and the Governor’s time limit was nearly up. Completely out of patience, Bob and Allen marched into the Dzong with a hundred soldiers and the Dzong officials, meeting no resistance. In an atmosphere of cordiality, they tried to make the Dzongpen understand that Tibet had ceded Tawang to India by the 1914 treaty. Nyertsang wanted to seek the Dalai Lama’s approval : “What approval ?” asked Bob. “ The Chinese have taken over Tibet”.

Finding his revolver was digging into his hip as he sat awkwardly on cushions placed on the floor, Major Allen suddenly took out his Smith and Wesson .38 and placed it before him. Nyertsang’s face instantly showed apprehension and he immediately became much less obdurate. In a little while all resistance was over. Nyertsang signed the instrument of accession drafted by Allen transferring Tawang to India, and was paid a nazrana of Rs.1000 for being such a nice chap. Bob Khathing signed for the Govt. of India. He then appointed Allen the Lt. Governor of Tawang, answerable only to the Governor of Assam, and to hold charge till a replacement arrived. Then he went off to Tezpur where Jairamdas sent his Dakota to collect him.

Jairamdas and Bob flew to Delhi to report what they had accomplished to Nehru. Far from praising them for severing the Gordian knot that had baffled the British, a livid Nehru ordered a complete blackout on the affair out of fear of adverse diplomatic fallout, and berated them for their ‘colossal stupidity’. Fate must have stood in the wings and smiled at Jawharlal’s outburst: in an ironical twist worthy of a Greek dramatist, Nehru’s own monumentally stupid adventurism would catch up with him eleven years later at the Thagla ridge in Tawang, lead to India’s greatest military humiliation, destroy Nehru’s inflated ego, and finally cause his death.

* * * * * *

India finally announced taking over the Tawang Tract in 1954, after the Indo-Chinese Trade Agreement had been signed on 29th April 1954. The Government belatedly recognised Bob Khathing’s fine work at Tawang by awarding him the Padma Shri in 1957.

In 1959 the Dalai Lama fled Chinese oppression and came to find asylum in India through Tawang. Fifty years later, speaking at Tawang on November 8, 2009, he acknowledged that Tawang and Arunachal Pradesh were integral parts of India, reversing the stand his government had taken in 1947.

Bob Khathing went from strength to strength : first Deputy Commissioner of Mokokchung (in Mills’ footsteps) in 1957, Security Commissioner of NEFA (equivalent to Brigadier) at Tezpur 1962-67, Chief Secretary of Nagaland 1967-71, then the first Indian Ambassador to Burma 1972-75. He died in Imphal in 1990, rich in years and honours. His birth centenary was celebrated fittingly last year.

Jairamdas Daulatram served as the Governor of Assam till 1956, putting the administration of both Assam and NEFA on a sound footing. He died in 1979, still a relatively poor man true to his Gandhian ideals. Jairampur town in Arunachal (Tirap Dist.) on the Assam – Arunachal border is named after him. In 1985 a 50 paisa postage stamp was issued in his honour.

Let us praise these men …

Uttorayon,

Siliguri,

July 4 -20, 2013

Most erudite commentary on recent political history of Tawang, A masterly and scholarly essay. I was in Tawang for nearly three years in late 70’s but its the first time I read the full story on Khating’s venture into Tawang and the role of intrepid Governor Daulatram.