Over a hundred men of Charlie Company, 13 Kumaon died fighting to the ‘last man, last round’ at Rezang La (Chushul) on November 18, 1962.

The Ottoman Empire was on its last legs. Midway through the Great War, the inter-allied French and British Commonwealth forces launched an assault to capture the Ottoman capital Istanbul to secure a sea route to Russia. Fought fiercely on the battlefields of Gallipoli peninsula, both fronts were weighed down by heavy casualties. Unable to crack the Turkish resolve, the Allies eventually beat a retreat.

The Turk sufferings during the campaign turned out to be the birth pangs of a proud nation. Eight years later, on 29 October 1923, the Republic of Turkey arose from the ashes of the Ottoman Empire. Mustafa Kemal (Atatürk), a commander at Gallipoli, led the Turkish National Movement that ultimately founded modern Turkey. In sum, the upshot of a bloody battle was the emergence of a new country.

The fizzle at Gallipoli recoiled in Britain: heads rolled; the backwash swept aside Winston Churchill who resigned as First Lord of the Admiralty; Prime Minister Herbert Asquith swallowed the bitter pill of sharing power with his adversaries by forming a coalition government.

Despite the mounting toll, despite depleting men and ammunition, Charlie Company intrepidly engaged the Chinese. They neither retreated nor surrendered. The gallant men fought to the last trench, last man, last round and last breath.

The Gallipoli backfire thus echoes what General Omar Bradley (the legendary commander of the US ground forces during World War II) mouthed: “In war there is no prize for the runner-up.” Whatever the cost and pain, victories are sweet and celebrated; licking the wounds leaves the defeated party with lingering sourness. More so because history is written by the victors who delight in turning up their nose at the vanquished. But if something inspires public imagination more than fabled conquests, stirs the emotion like nothing else in the world, it has to be the tales of gallant last stands. Let me cite some.

Thermopylae

Circa 480 BCE. To stem the advance of the Persian invasion of Greece, Athenian general Themistocles urged the Greek king to adopt a two-pronged strategy: one, block the narrow coastal pass of Thermopylae; two, naval siege of the straits of Artemisium to forestall the Persians from skirting Thermopylae by sea.

Spartan King Leonidas mobilised an allied Greek army of approximately 7,000 men to make Thermopylae impassable to the formidable army of Xerxes, who was itching to avenge his father’s drubbing at Marathon. Although vastly outnumbered, the Greeks held more than a quarter million Persians at bay until Ephialtes – a local – ratted on them by divulging to the Persians the mountain pathway to the rear. Outflanked, Leonidas bid his army to retreat but for the phalanxes of 1,400 hoplites (armed-to-the-teeth foot soldiers) to forge a do-or-die rearguard.

The rearguard clashed with the Persians over the pass, initially with spears and later with xiphes (short swords). Leonidas died fighting. Upon sensing his moment, Xerxes marshalled his troops to the hills to rain down arrows till the last hoplite was slain. While the Greeks suffered 2,000 fatalities, the chroniclers put the Persian toll at ten times that count.

The epitaph inscribed on the plaque of the Thermopylae memorial reads:

Go tell the Spartans, thou who passest by,

That here, obedient to their laws, we lie.

Thermopylae could not queer the Persian invasion but the moving epic scripted by Leonidas remains one of the most narrated last stands in history.

Saragarhi

Saragarhi, a small village in present-day Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa of Pakistan, staged one of the bloodiest encounters during the Tirah Campaign. Pitted against corps of Afghans, a contingent of 22 soldiers of the 36th Sikh Regiment of British India led by Havildar Ishar Singh, chose to fight to death to defend the army post and authored another gripping last stand on 12 September 1897.

Unlike Thermopylae, the Battle of Saragarhi was an instance of the self-sacrifice not going in vain. The Sikhs had fought long enough to allow the British to rush reinforcements…

Tribal Pashtuns raided British encampments from time to time. Situated midway between forts Lockhart and Gulistan, the British raised Saragarhi as a heliographic communication post. Since their offensives to conquer the forts were thwarted by the Sikhs, to disrupt the communication between the two forts, 10,000 Afghan tribesmen launched a fierce onslaught on the Saragarhi post that September day.

Screaming the war cry of Bole So Nihal, Sat Sri Akal, the Sikhs confronted the Afghans head on. Havildar Ishar Singh displayed exemplary courage and leadership in defending the swarmed post located on a rocky ridge. Sardar Gurmukh Singh, the last Sikh defender, loosed off a whirlwind attack that killed a score of Pashtuns. The Afghans had to set fire to the post to snuff out the valiant Sardar.

Unlike Thermopylae, the Battle of Saragarhi was an instance of the self-sacrifice not going in vain. The Sikhs had fought long enough to allow the British to rush reinforcements, who drove away the droves of Afghans essaying to capture Fort Gulistan. In sum, Saragarhi turned out to be a pyrrhic victory for the Afghans.

Camarón

Captain Jean Danjou of the 3rd company of the Foreign Regiment detachment was charged with escorting a logistics convoy to bolster the siege by the French Legion of the Mexican city of Puebla. No sooner had they halted at Palo Verde for the daybreak coffee-break than he heard the clip-clop of mounted Mexicans. His immediate task was to divert the attention of the pouncing cavalry from the convoy nearby. So he mustered his men at Hacienda Camarón with dispatch and converted an inn with three-metre-high parapet into a rampart.

The date was 30 April 1863. Colonel Milan, the Mexican commander bade him to surrender but Capt Danjou retorted he and his men would rather fight to death than submit. The 65 legionnaires bravely took on the combined might of 800 horsemen and 1,200 infantrymen. The fusillade from French long-range rifles dispersed several Mexican forays. Capt Danjou took a shot right in the chest at midday and passed on. Second Lieutenant Vilain took charge and galvanised the Legion ranks to give the Mexicans a bloody nose, till he too fell. With just 12 legionnaires left, 2nd Lt Maudet took over the mantle. Ammunition ran out in an hour in the shoot-out, and the five men still standing roared and lunged into a desperate bayonet charge.

In the battle of Rorke’s Drift (South Africa), the last-standers actually outfought and repulsed the superior foe and lived to fight another day.

Colonel Milan asked the two survivors left to lay down their arms but they sought safe passage home to escort the body of Capt Danjou. The Colonel conceded out of sheer respect for their valour.

Like the 36th Sikh regiment, the 3rd company’s sacrifice was not futile; the convoy did make it to Puebla and the city fell 17 days later.

Captain Danjou had lost his left hand in an expedition and had a prosthetic hand appended to the forearm. April 30 is venerated as “Camerone Day”, and the Legion parades the prosthetic hand to commemorate the battle of Camarón, which continues to inspire the posterity.

Rorke’s Drift

The general drift is the stronger force trouncing the weaker one, more so in a last stand, but not always. In the battle of Rorke’s Drift (South Africa), the last-standers actually outfought and repulsed the superior foe and lived to fight another day.

The defence of Rorke’s Drift was an engagement during the Anglo-Zulu War fought between the British Empire and the army of Zulu king Cetshwayo at the border between the British colony of Natal and Zulu Kingdom about the eponymous ford near the Mzinyathi River. On 22 January 1879, about 160 British and assorted colonial troops (belonging to B Company of 2/24th Regiment of Foot under Lieutenant Gonville Bromhead and 5th Company of Royal Engineers led by Lt John Chard) parried repeated attacks by four regiments of Zulu warriors and triumphantly defended the garrison. The stout defence radiates more lustre when beheld against the backdrop of the British army’s rout at the Battle of Isandlwana just the previous day. For the record, beginning with the tactical victory at Rorke’s Drift, the British forces notched up series of victories to finally defeat the Zulu nation at the Zulu capital Ulundi on July 4. This last stand is truly sui generis.

Karbala

As he neared his death, Mu’awiya, the calculating governor of Syria, Palestine & Jordan, anointed his son Yazid as his successor. Husain ibn Ali, the grandson of Prophet Muhammad, crossed swords with Mu’awiya for he opposed this deviation from a canon of Islam (does not subscribe to dynastic/monarchical rule). Later, upon Mu’awiya’s death, Yazid ascended as the governor. He yearned for public acceptance, and like his father, had no hesitation in using means fair or foul towards fulfilling that end, but Husain steadfastly refused to accept Yazid as a leader of Islam or a caliph.

The battle of Karbala and the tragic events were like a mighty quake that shook the foundations of Islam.

680 CE. Meanwhile, its people invited Husain to Kufah and impelled him to assume as their leader. He and his supporters set course from Mecca to Kufah, but en route, they were intercepted by Yazid’s troopers and forced to encamp at Karbala, west of the Euphrates River. Five days later, Yazid’s forces completely laid siege and cut off access to Euphrates to deprive water to Husain and his band. But Husain refused to surrender.

Three days later, the day of Ashurra dawned upon Karbala. On the tenth day of Muharram, hostilities finally broke out; just 71 warriors arrayed against the might of 5,000-strong army of Yazid. As the dehydrated, exhausted men engaged the formidable army, Husain expected help to arrive from Kufah, but that never materialised. One by one, they embraced martyrdom, Husain being the last to fall. Ali Asghar, six-month-old baby and his youngest son, was not spared and died before his very eyes.

The battle of Karbala and the tragic events were like a mighty quake that shook the foundations of Islam. The significance of Karbala is that it has solidified into a keystone of the Shia faith, whose followers believe the 72 innocent lives sacrificed did not go in vain, for it saved Islam and the Ummah. For them, Karbala was actually a triumph, of good over evil.

Tarawa

To impose itself across the mid-Pacific and advance towards Japan during the latter half of the Second World War, the US needed to establish insular airbases, and this island-hopping strategy zeroed in on the occupation of the Marshall Islands first followed by the Marianas Islands, but to capture the Marianas, they had to first seize the Japanese-controlled atoll of Tarawa.

Anticipating an amphibious American invasion, the Japanese 3rd Special Base Force fortified the islets with coastal batteries and ring-fenced the inland with stockades and firing pits. The US 2nd Marine Division comprised a flotilla of 143 vessels and 18,000 Marines. The invasion of the largest islet Betio commenced in the predawn hours of 20 November 1943; guns blazed, aircraft blitzed, bombshells banged, but the attempts to establish beachheads were bogged down by deadly Japanese gunfire and shallow tide. Though the death of commander Keiji Shibazaki threw the Japanese response into disorder, by nightfall the garrison had eliminated 1,500 of the 5,000 Marines ashore.

The Japanese soldiers fought almost to the last man; of the 3,636 Japanese fighters who defended Tarawa, only 17 outlived the 76-hour relentless American onslaught.

On the second day, to elbow ahead, the Americans brought their heavy artillery to bear on the Japanese emplacements and established control over the western end of the island. The tide had turned, literally and figuratively! The next day, they consolidated their grip over Tarawa, pushed the Japanese further into the interior and moved in the heavy hardware.

Their backs against the wall, in the wee hours of 23rd, about 300 Japanese soldiers launched an inspired banzai charge, but were outgunned by the Americans in an hour. The Marines later stormed to mop up the remaining obstinate Japanese.

The Japanese soldiers fought almost to the last man; of the 3,636 Japanese fighters (plus 1,200 Korean labour) who defended Tarawa, only 17 outlived the 76-hour relentless American onslaught. The US paid dearly too, with 3,301 casualties.

Königsberg

The Second World War had slogged into the sixth year. Retribution on their mind, the Red Army was on the offensive and at his threshold (East Prussia), but Adolf Hitler chose to mind the Ardennes Offensive (Battle of the Bulge) in the west instead.

The 1.5-million strong Byelorussian Front bustled into East Prussia in January 1945, and encircled the city of Königsberg. Its residents could bolt only via the Baltic port of Pillau or Danzig. The evacuations to Germany and Denmark, christened Operation Hannibal, a venture that matched the scale of the great evacuation at Dunkirk, began on January 23. With the Nazi atrocities still raw and galling, the Soviets went on the rampage to avenge, unleashing bestial savagery in the process, annihilating thousands of refugees, on land and sea.

The Wehrmacht, enfeebled, bloodied but unbowed, counterattacked to open a corridor between Königsberg and Pillau, which held till early April. While the civilian evacuations carried on apace, General Otto Lasch of the Königsberg garrison used his debilitated military to launch guerrilla attacks from their foxholes and pillboxes. The stunned Soviets responded by ferocious aerial bombing and artillery shelling, following through with a massive land assault by troops just drilled in urban warfare. With casualties mounting, Gen Lasch radioed Hitler for the nod to surrender, but was told to get even with the Russkies.

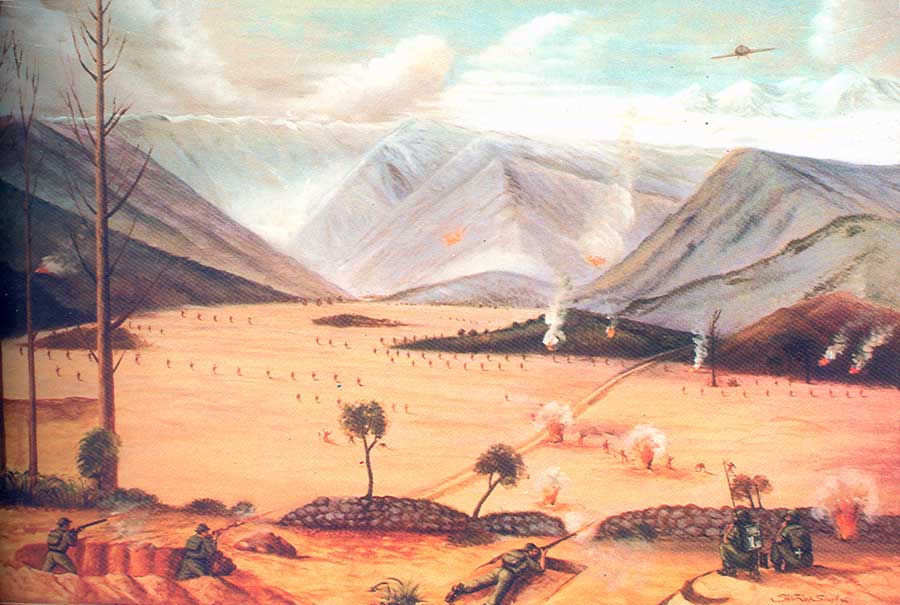

In 1962, the Chinese Army planned to attack Chushul via the Spanggur Gap along the road from Rudok, and the Chushul-headquartered 114 Infantry Brigade of the Indian Army was tasked to foil the Chinese invasion.

The shooting raged on. Multitudes of terrified, fleeing residents were mercilessly massacred – shot or strafed – and the vessels ferrying them were torpedoed. Overwhelmed by the tragedy and cruelty, Gen Lasch surrendered and the fighting ceased by midnight of April 9. Livid, Hitler ordered Gen Lasch’s execution but there were none to enforce the diktat, for Königsberg was under Soviet jackboots!

Königsberg overrun, the Red Army goose-stepped towards Pillau. The 20,000-strong plucky German garrison there fought tooth and claw, inflicted colossal havoc but in the end the Soviet juggernaut crushed their stiff defiance, forcing them to wave the white flag on April 26 to avert another carnage.

Post-war, Joseph Stalin annexed East Prussia. Königsberg was renamed Kaliningrad. Thousands of Germans were banished, several hundreds packed off to Soviet gulags, and many preferred suicide instead of succumbing to Soviet brutality. The Russification completed once the planted settlers of Russian, Belarusian and Ukrainian stock struck root there.

One may split hairs whether the Battle of Königsberg can be categorised as a last stand, but what is unarguable are the unspeakable horror let loose on the populace and the hopeless but heroic resistance against the numberless, ruthless raider.

Rezang La

From the south bank of Pangong Lake in Ladakh, a cluster of high mountains slopes towards the Spanggur Lake. A 2-km-wide clean gap exists in this range known as the Spanggur Gap. The Spanggur Gap joins the Chushul plateau in the west to the Tibetan plateau to the east. The village of Chushul lies west of the Spanggur Gap.

In 1962, the Chinese Army planned to attack Chushul via the Spanggur Gap along the road from Rudok, and the Chushul-headquartered 114 Infantry Brigade of the Indian Army was tasked to foil the Chinese invasion.

In all, 113 died with their boots on; five wounded were taken prisoners of war, of whom one expired in captivity; six gravely injured (including Naik Ram Kumar Yadav), mistaken as dead, later staggered back to the battalion HQ. The PLA sustained well over 500 casualties.

Overlooking the Chushul plains on the east, Gurung Hill, Muggar Hill and Rezang La form a towering massif, and the Chinese Army obviously had to get past it to smell the Chushul air. Rezang La, a pass, is nearly 11 km south of Spanggur Gap. The craggy, snowy heights about Rezang La, a feature with ginormous girth, soar to 5200 metres. Rezang La guards the southeastern approach to the Chushul Valley and its occupation would enable the Chinese to cut off the single road that linked Chushul to Leh via Dungti – the lifeline of the Chushul garrison.

Starting October 27, there was a lull in the war that enabled India to fortify her defences and China to further build up their strength in the Spanggur area. 114 Inf Bde had tasked the just-inducted 13 Kumaon battalion to cover the southern flank of Spanggur Gap. Lt Col H S Dingra, the commanding officer who was hospitalised but had inveigled the doctors into letting him rejoin his boys, assigned two companies to the defence of Muggar Hill and the Charlie Company with a section of 3-inch mortars to Rezang La.

Major Shaitan Singh Bhati, officiating as the battalion quartermaster, was told to assume charge of Charlie Company. Though the Himalayan winter made it arduous, he had his 123 men of three platoons and the mortar section prepare sangars and defensive positions about their over-two-km-broad company defended locality. The topography shut out his company from the rest of his battalion (the nearest was a company of 5 Jat located at Tsakala), which meant reinforcement was out of the question. The shortage of field guns deprived him of artillery cover. Besides having to prepare to face the enemy from all directions, geospatial isolation also meant that his company could not influence the battle much. Worse, none of the equipment of the Indian Army was designed for operating in subzero-temperature. Odds stacked one upon another, yet the Major did not give up halting the Chinese charge as lost cause.

The People’s Liberation Army commenced the battle for Chushul in the wee hours of November 18. At Rezang La, it was a frigid, windy morning for a two-hour storm had lashed the area with snow and gale the previous night, making clasping of weapons tad more difficult than it already was.

A battalion of the PLA launched raids from the south and the east. The nullahs they were trudging bogged them down, leaving them sitting ducks for the Indian mortars and grenades. The lucky survivors took cover and retraced.

Having been repulsed, the Chinese changed ploy and resorted to artillery and mortar fire, which was ineffective but destroyed the company’s communication lines to the battalion HQ. On sighting the ‘pyrotechnics’, the post at Tsakala raised the Kumaon HQ (oblivious of the showdown), but reinforcements would take hours to make it. With even radio gone, the company commander knew they had to deal with the Chinese all alone.

The frontal attack having misfired, the Chinese revised tactic and launched another wave of attack on Rezang La, in strength, this time from three directions, under the cover of artillery barrage. In an attempt to beat back the assault by two companies on the rear platoon, Jemadar Surja Ram and his men engaged the Chinese in a hand-to-hand combat. All men of this platoon died fighting.

Major Shaitan Singh hustled from trench to trench, sangar to sangar, redeploying the LMGs and spurring his men on. Soon, withering machinegun fire mowed down the Chinese troops and Rezang La was strewn with motionless bodies of Chinese troops.

Meanwhile Major Shaitan Singh was hit grievously in the abdomen by MMG sniper-fire but refused evacuation and succumbed to injuries.

The hard, bitter, bloody battle raged on. Wave after wave of Chinese reinforcements emerged to wear down the Indians. Despite the mounting toll, despite depleting men and ammunition, Charlie Company intrepidly engaged the Chinese. They neither retreated nor surrendered. The gallant men fought to the last trench, last man, last round and last breath. Ultimately, the boom of gunfire that resonated off the hills ceased resounding, and brought the shroud down on the last stand at Rezang La.

The last stand at Rezang La stands out and exemplifies the embodiment of soldiering – selfless devotion to duty even in the face of death.

The nation learned of their courageous fight only when the Indian Army took possession of the bodies in February 1963. Captain Amarinder Singh noted in his book Lest We Forget: “In an unusual mark of respect for which the Chinese are not usually noted, their bodies had been covered with blankets, pegged down with bayonets. There could have been no greater tribute to their courage than this acknowledgement by their enemy.”

All casualties bore multiple bullet and splinter injuries. Not to mention their frozen hands still clutching their weapons but without ammunition. The mortar man died with a bomb in his hand. The medical assistant held a syringe of morphine and bandage.

The 96 bodies recovered from the battlefield were cremated on a common pyre. In 1965, a shepherd recovered two bodies at a LMG position on a flank. In all, 113 died with their boots on; five wounded were taken prisoners of war, of whom one expired in captivity; six gravely injured (including Naik Ram Kumar Yadav), mistaken as dead, later staggered back to the battalion HQ. The PLA sustained well over 500 casualties.

The nation honoured the exceptional valour of Charlie Company with gallantry gongs. Major Shaitan Singh was decorated posthumously with the Param Vir Chakra. Jemadar Surja Ram (posthumous), Jemadar Ramchander, Jemadar Hari Ram (posthumous), Naik Ram Kumar Yadav, Naik Hukam Chand (posthumous), Naik Gulab Singh (posthumous), Lance Naik Singh Ram (posthumous) and Sepoy Dharampal Dahiya (posthumous, of Army Medical Corps) were conferred the Vir Chakra. The Sena Medal was bestowed on CHM Harphul Singh (posthumous), Havildar Jai Narain, Havildar Phool Singh and Sepoy Nihal Singh. Jemadar Jai Narain (posthumous) was mentioned in despatches.

Brigadier Ashok Malhotra, the author of Trishul Ladakh and Kargil 1947-1993, recalls the mind-boggling account of Naik Ram Kumar Yadav, the mortar section commander. I paraphrase: Though his body was riddled with nine wounds, he kept directing the fire of mortars until a Chinese grenade knocked him flat, nose completely blown off. Presuming him to be dead, the Chinese picked him, threw him into a bunker and set it afire. The heat of his burning clothes jolted him into life and he leapt out of the bunker. Seeing his condition, the Chinese let him be. As he began trudging, he slipped, hurtled down a slope and went unconscious. He regained bearings later and wended six miles to the battalion headquarters to recount the incredible valour of his comrades-in-arms.

The last stand at Rezang La stands out and exemplifies the embodiment of soldiering – selfless devotion to duty even in the face of death. It inspired Chetan Anand to make the classic film Haqeeqat.

The Indian Army enshrined their martyrdom in a memorial at the site of mass cremation near Chushul. It is a simple white marble pillar with the names of 114 martyrs etched on two sides, in Hindi and in English. The following lines (the first four from Thomas Macaulay), poignant yet stirring, inscribed on the third side pay homage to their deed:

How can a Man die better

Than facing Fearful Odds

For the Ashes of His Fathers

And the Temples of His Gods

To the sacred memory of the Heroes of Rezang La,

114 Martyrs of 13 Kumaon who fought to the Last Man,

Last Round, Against Hordes of Chinese on 18 November 1962.

The Charlie Company comprised Ahirs who hailed from the Rewari district of Haryana. Rewari raised a monument for its brave sons who laid down lives for the motherland in Gudiani village. It is a granite slab emblazoned with the names of the martyrs, radiating their intrinsic courage with the hurrah shoorveeron mein ati shoor veer – veer Ahir. Reportedly, the inert administration has let the gated Rewari memorial go to seed.

The last stand

Battle of Roncesvalles, Custer’s last stand, the Alamo, Siege of Masada, Iwo Jima, Siege of Khartoum, Wadborough Hill, Napoleon’s Imperial Guard (Battle of Waterloo), Stalingrad – the bloodiest of them all, … fascinatingly, though as rare as the dodo bird, military history is still rich with recitals of last stands. By the way, the Pakistanis believe that in the 1965 Indo-Pak War, once the 1st Armoured Division of the Indian Army pulverised their 6th Armoured Division at Phillora in one of the most furiously fought tank battles of the war, the remnants retreated and regrouped to put up a last stand at Chawinda.

We dub the Indo-China War as the ‘1962 debacle’, which indeed it was. But while doing so, we forget that the Indian soldier has invariably never flinched from his duty even in the most trying environment.

It is but natural for the last stands to inhabit our consciousness as inspirational deeds of gritty heroism. Why do soldiers resort to a last stand when they know it is suicidal and hopeless, and the enemy will all but overrun them? A surge of adrenaline? To uphold their honour? Are there moral and cultural dimensions to it? At a higher plane, is fight to the last ditch a tactic like what happened at Camarón?

Well, the whys and wherefores of last stand would challenge even the most eminent psychoanalyst. Militarily, if a cornered force believes that their sacrifice can contribute to the larger cause, maybe even the outcome of war, if the commander finds the benefits of a final duel outweighing the benefits of surrender or retreat, a last stand is on.

But to inspire and lead troops on to a last stand, the commander must truly command the absolute allegiance of his men, be a standard-bearer like King Leonidas, Havildar Ishar Singh, Captain Jean Danjou, Lieutenant John Chard, Husain ibn Ali and Major Shaitan Singh were.

Lest we forget

It is 50 years since that dismal November. We dub the Indo-China War as the ‘1962 debacle’, which indeed it was. But while doing so, we forget that the Indian soldier has invariably never flinched from his duty even in the most trying environment. Here’s a quote from the 30 November 1962 edition of Time magazine: “…the fighting has shown that the Indians need nearly everything, except courage.” No wonder then that any epic of heroism pales beside the saga of Rezang La. Let us proudly remember the lion-hearts of Charlie Company on November 18.

This article was first published in 12 November, 2012.

my father now 80 year old one of the survivor of rezang la war 1962 there is no honour from army

sab bakwas

from

narendra kumar yadav

LET THE WIDOWS , DAUGHTERS AND SONS OF THESE BRAVE WARRIORS BE DECORATED AND SALUTED ON THE REPUBLIC DAY 2015 HOSTED BY THE PRESIDENT AND REWARDED BY THE GOVT AND ARMY ON THE 53RD ANNIVERSRY OF THE BATTLE OF REZANG-LA

A well written and motivating article which elevates the battle of Rezang la to an high alter of Bravery and valour more such articles from the author would be appreciated for his diction and naration

MP Anil Kumar’s article enlightens us about the bravery of soldiers and the battles described in the article are unique in the annals of military history. Two of the battles involve Indian troops which should make every Indian proud. Unfortunately the politicians then, and the politicians today have little regard for the Armed Forces of this country. Those interested can read my blog on the Charlie Company’s last stand written on 18th November.

kumar-theloneranger.blogspot.in/2013/11/rezang-la-13-kumaons-last-stand.html

Jai Hind

Dear sir,

Excellent piece of information. Every drop of my blood inviogerated after reading battle of Shaitan singh.

Considering your utmost human limit, I salute to ur dedication for nation.

Sincerely,

Shital Gandhi

Amsterdam

sir

v good contribution

Mr. Asthana, poor planning at rezangla was a failure on part of top leadership and not of jawans. You need to be a soldier to understand feeling of izzat of your clan and paltan. Those who fell valiantly at Rezangla were not fools but worthy sons of mother India who fought to the last and kept dying one by one. You do not get victory through good military planning only; it also requires guts and blood of valiant men like the Ahir warriors of Rezangla. We should learn how to honour our martyrs. Jai Hind.