The eve of Republic Day is, by tradition, when National Awards are announced. The day is also one to remember recipients of the highest National Award for courage, the Param Vir Chakra. Good reason, if we need it, to remember a young Indian Air Force pilot who 45 years ago, almost to the day, became the first — and still the only – IAF recipient of the Param Vir Chakra.

The eve of Republic Day is, by tradition, when National Awards are announced. The day is also one to remember recipients of the highest National Award for courage, the Param Vir Chakra. Good reason, if we need it, to remember a young Indian Air Force pilot who 45 years ago, almost to the day, became the first — and still the only – IAF recipient of the Param Vir Chakra.

On December 14, 1971, India was 11 days into the war which resulted in the liberation of Bangladesh. The Indian Army had been making such rapid advances on the Eastern Front that it was already obvious that a conclusion must be only a few days away. Most public attention was on the tightening noose around Dacca (Dhaka).

But there was still plenty of action on the Western Front.

The Second Corps of the Pakistan Army was said to be preparing an offensive. The Pakistan Air Force, which for a few days had not been active, claimed afterwards that they had been conserving their assets to support this all-important offensive. But they were keeping up attacks on Indian airfields — those of Amritsar, Pathankot and Srinagar in particular. The Indian Army was at this time mounting a limited offensive in the Shakargarh bulge, with IAF aircraft providing close support, so the Pakistan Army and Air Force were keen to neutralise these airfields specifically.

Srinagar was a relatively easy target, and Pakistani F-86 Sabres raided it frequently during the war. In compliance with the conditions of the 1948 ceasefire, India did not station fighter aircraft in Srinagar during peacetime; so the small IAF detachment there, drawn from No.18 Squadron IAF, had only just moved in. The personnel were not familiar with the environment,or acclimatised to the cold. In addition, the Kashmir Valley had no radar coverage, so early warning was dependent on Observation Posts on peaks along the Pir Panjal range — basically a few soldiers, sometimes with binoculars. The Sabres came over early in the morning, cloaked by winter fog, so even the OPs couldn’t always spot them.

The Sabres caused some damage, but if and when they hit the runway, Indian repair crews put it back in use quite promptly. In an interesting sidelight, the Sabres had dropped leaflets with warnings to the local Garrison Engineer not to repair the runway, threatening to bomb his house otherwise. The GE was said to have taken this as a compliment.

Early on the morning of December 14, the Pakistan Air Force launched yet another raid on Srinagar. Six Sabres threaded their way through the valleys between the hills and burst upon Srinagar airfield. Four of them, each carrying two 500-pounder bombs, pulled up to 1,500 metres and nosed over, aiming to drop their bombs at intervals along the runway. The other two set up a loose orbit, for top cover.

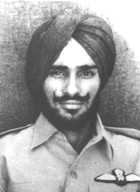

The two Indian pilots on readiness that morning were Flight Lieutenant B.S. Ghuman and Flying Officer Nirmaljit Singh Sekhon. Flt Lt Ghuman had just re-joined the squadron as part of the strengthening of all combat units which had taken place on the outbreak of the war. He had, as it happens, been Fg Off Sekhon’s instructor a few years earlier. Fg Off Sekhon, hailing from Ludhiana, was the son of a Warrant Officer, recently married, and the proud owner of a Jawa motorcycle. He was full of determination and ‘josh’, and bent on getting to grips with the enemy.

Because of the foggy conditions and poor visibility that morning, Ghuman and Sekhon had actually been released from readiness, but told to hang around “just in case”. When the air raid warning blared, if truth be told, the base may have let its guard down a little.

Nevertheless, Ghuman and Sekhon were in their cockpits, with engines started, within the usual readiness time. But they were held up at the runway threshold, engines running and leaning on their brakes, by Air Traffic Control (ATC). It is normal practice not to clear take-offs during a raid, to allow the base’s own anti-aircraft gunners to fire freely; and also because the need to accelerate in a straight line down the runway makes the aircraft taking-off highly vulnerable to the raiders.

The Combat Air Patrol controller, who operates on a different frequency from ATC, tried to communicate with Ghuman and Sekhon, but they were both listening intently on the ATC frequency, hoping for permission to take off. When the first two bombs exploded on the runway, Ghuman, eager and on edge, on his own initiative, released his brakes and roared down the runway.

Sekhon, equally eager, took his leader’s take-off as clearance for himself; but had to hold back for a few moments, because the clouds of dust raised by Ghuman’s Gnat had cut his visibility to zero. By the time it had cleared enough for him to see, two more bombs had exploded. Sekhon, fiercely determined, opened his throttle wide, released brakes and followed his leader roaring down the runway.

As it happens, the four bomb-carrying Sabres were attacking along the line of the runway, from directly behind the end from which Ghuman and Sekhon had commenced their take-off rolls. So, as Sekhon lifted off, the two Sabres which had already dropped their bombs were directly ahead of him – and the other two were directly behind.

Sekhon tore after the first Sabre pair, who were re-forming after their bombing runs. The Sabre leader (who, it was later discovered, was their squadron commander), an experienced veteran of combat in 1965, spotted him and yelled: “Gnat behind, all punch tanks”. The third Sabre, just pulling out, was described in an unusually clear-eyed Pakistani account as follows:

“ … horrified to see the Gnat no more than 1,000 ft and firing at Dotani [the Pakistani No 2] … who had been turning frantically, [and] found his low-powered Sabre tottering at the verge of stall. Unable to hang around any longer with such a precarious energy state, he decided to make a getaway. No 4 … in the meantime had completed his bombing run and … decided to head home as well.”

Experienced combat pilots draw very strong conclusions about other pilots’ intentions and the threat they pose, from the way they fly, the manner in which they turn their noses towards the enemy (to fight), away (to flee), or waver. Sekhon’s sheer determination, visible in the way he was heading straight for the Sabres had, within moments of his joining combat, clearly unnerved the four Pakistani pilots of the bomb-carrying section, two of whom had already disengaged and turned for home.

As the two remaining Sabres at low level curved away, the fight turned into a classic circling tail chase: the Sabre leader being pursued by Sekhon’s Gnat, which in turn was being pursued by the No.3 Sabre. “I’m in a circle of joy, but with two Sabres. I am getting behind one, but the other is getting an edge on me,” Sekhon’s voice crackled over the radio.

The No.3 Sabre, behind Sekhon, was firing continuously. Sabres are fitted with six guns, which between them carry no less than 1,800 rounds of ammunition. “The Sabre had enough firepower to riddle a whole formation with bullets,” the Pakistani account continues, “so everyone was dumb-founded when Andrabi [their No 3]’s voice crackled on the radio, ‘Three is Winchester!’” [‘Winchester’ in this context means ‘out of ammunition’.] The No.3 Sabre had used up all his ammunition on Sekhon, without success.

“Andrabi was a class unto himself when he took to the radio,” the Pakistani account continues. “ …. [His] expletives ensured that his calls were never disregarded even in the toughest of air combat manoeuvres. Thus, when Andrabi shouted for help against the attacker, whose lineage he had declared suspect, everyone took notice!”

The Sabre leader called for the No.3 to form on him, and as they were doing so, Sekhon took advantage of the moment, and jettisoned his drop tanks. The Pakistanis realised that the Gnat could now turn even more tightly, and started to catch up with the Sabre pair. The other Sabre pair, still providing top cover above, was said to have “watched in astonishment as the Gnat snatched degrees at a dizzying rate. The situation was getting stickier by the minute and in a couple of turns the Gnat was in a menacing position.”

Finally, the Sabre leader called for the escort pair to join the combat. The two escort Sabres dived down to grapple with Sekhon. By that time, Sekhon had effectively scared away two of the original six attacking aircraft, and even on a one-against-two basis was giving such a hard time to the remaining two that one had run out of ammunition and they had to call for help.

The sub-section leader of the escort pair was another experienced combat pilot, who had shot down an IAF Hunter on the first day of the war. Diving down from above, with the advantage of height, he latched on behind Sekhon and opened fire. Sekhon’s Gnat started to spew thick black smoke.

Sekhon was still full of fight, and tried to call to his leader and old instructor: “I think I have been hit. Ghuman, come and get them.”

Ghuman, in the heat of the moment as he took off, had taken the tactical decision to climb higher, to give himself height and energy with which to pursue the diving raiders. In the odd meteorological conditions over Srinagar at the time, had found himself above the layer of haze, and unable to spot the swirling combat below. As we had no radar coverage, controllers on the ground could not help.

Watchers, both the Pakistani pilots and Indians below, saw Sekhon’s hard-manoeuvring Gnat level its wings for a moment. Suddenly, the Gnat pitched down uncontrollably from very low height. It is possible that the aircraft’s elevator controls had failed – the Gnat was notorious for a potentially fatal problem with elevator trim. Sekhon’s canopy was seen to fly off, as he seemed to attempt a last-minute ejection, but he was far too low.

A search party found the wreckage of Fg Off Sekhon’s Gnat in a gorge, a few miles from the airfield. His squadron mates counted 37 bullet holes in the recovered parts of the wreckage. The location was Badgam — coincidentally, almost exactly where, in November 1947, India’s first Param Vir Chakra recipient, Major Som Nath Sharma, had fallen in defence of the Valley.

When the citation for Flying Officer Nirmaljit Singh Sekhon’s Param Vir Chakra was written immediately after the battle, he was credited with having “scored hits” on one enemy Sabre and having set fire to another. The reconstruction, many years later, with inputs from participating PAF pilots, suggests that he did not actually hit any of them that severely; but it is clear that his fighting approach prompted genuine respect, and even some alarm. This account includes several quotes from an article[i] by the respected Pakistani pilot and writer Air Commodore Kaiser Tufail, in which a certain healthy respect for Sekhon comes through. The enemy’s respect is always the most sincere tribute to a warrior’s heroism, reflecting credit on both sides.

There is an excellent, painstakingly accurate animated reconstruction of Sekhon’s epic dogfight, done by IIT Kharagpur alumnus and VR professional Anurag Rana, at the following link[ii], which helps to visualise his courage: https://youtu.be/xiL_H92K1Tk

Let us take a moment on this day, to remember Flying Officer Sekhon’s heroism. It remains our responsibility, to continue building an India, and Indian institutions, that are worthy of his sacrifice, and those of others.

——————-

i] “A Hard Nut to Crack”, in Great Air Battles of the Pakistan Air Force by M Kaiser Tufail, Ferozsons 2005, reproduced at the author’s blog, http://kaiser-aeronaut.blogspot.in/2008/11/hard-nut-to-crack.html

ii] Rana has also done an even more moving animation of an incident during the Kargil War of 1999, when we lost a Mi-17 because the crew accepted an aircraft on which the anti-missile counter-measures were not functioning.

A fairly accurate and interesting account of the air battle which took place on Dec 14 , 1971.I happened to be the leader of escort pair of Pakistani Sabres attacking Srinagar airfield.