The development of the National Socialist Council of Nagaland-Isaac Muivah (NSCN-IM) must be first viewed through the broader context of the changing nature of insurgency in Northeastern India. The Northeastern region of India comprising the states of Assam, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland and Tripura has witnessed a significant number of casualties as a consequence of armed conflict. These casualties are distinct from those that have occurred as a result of inter-ethnic tensions, which manifest themselves in the forms of riots and which also lead to significant internally displaced populations.

Traditional approaches to research on armed groups in conflict studies have examined armed conflicts mainly in their political context. Thus, for instance, we are aware of the factors that allowed for the establishment of these groups, their political motives, the nature and types of violence perpetrated by the group as well as the strategies of the state in either combating or co-opting them.

This is especially applicable to the study of armed movements in North-eastern India, a region which has witnessed a continuous emergence and evolution of such groups. One of the fundamental characteristics of the study of armed movements in the Northeast is the focus on the strategic aims of these groups relative to the state. However, there is very little evidence on endogenous or internal dynamics of such movements.

This partly arises from the fact that armed movements are extremely difficult to access and there is an absolute lack of knowledge on their internal dynamics, beyond the more visible actions of their leadership. However, the increasing continuity and resilience of these movements (as witnessed in the various events reported throughout the region) requires a reformulation in terms of the questions being raised. Thus increasingly, it has become necessary to reinterpret these movements, not through their political, but rather through their sociological forms. Armed movements in the region are unique, primarily because of the motivations that drive individuals to join such groups. Not only do these movements provide an alternative vision to their adherents or supporters, they also tend to be driven by identity (more specifically ethnic) factors as well. This is not to underestimate the various push factors as well which include underdevelopment, the lack of opportunities, discrimination, and marginalisation. However, explanations that purely attribute recruitment to economic factors need to be combined with identity centric perspectives to provide a more holistic solution to the problem of rebel recruitment.

Given the above context, the article seeks to address the notion of resilience of armed movements. However, this question of resilience will be explored through a series of pamphlets produced by the Government of the People’s Republic of Nagalim (GPRN) which provide a window into the sociological dimension of the armed movement (the NSCN-IM). The article thus will present a preliminary content analysis of these pamphlets, and will describe the manner in which, ideological solidarity functions within the group. Lastly, the article will conclude with the argument that there is need for more micro-foundational work on armed movements in Northeast India to understand the factors that are driving recruitment.

The NSCN (IM) is not considered a banned armed outfit, but rather as a political movement…

History and Background: The NSCN-IM and the Naga Armed Movement

The development of the National Socialist Council of Nagaland-Isaac Muivah (NSCN-IM) must be first viewed through the broader context of the changing nature of insurgency in Northeastern India. The Northeastern region of India comprising the states of Assam, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland and Tripura has witnessed a significant number of casualties as a consequence of armed conflict. These casualties are distinct from those that have occurred as a result of inter-ethnic tensions, which manifest themselves in the forms of riots and which also lead to significant internally displaced populations. As stated by Lacina (2009) in describing patterns of insurgency in Northeastern India, “A more important factor behind ongoing insurgency is the weakness and corruption of formal political institutions in the region. Many of the small insurgent groups in the Northeast lack the capacity to launch attacks on central government targets. Instead, they flourish by simultaneously partnering with and preying on weak local governments through extortion, partisan clashes and criminality.”1 Four major characteristics of conflict processes in the Northeastern region, which can be extended to understanding the situation in Manipur as well, must be mentioned:

- First, the presence of ethnically constituted armed groups that are not only fighting against the state for secession or autonomy, but are also engaging in armed clashes with other groups, over territorial control and economic resources.

- Second, the transnational nature of these groups, whereby they are able to create sanctuaries in neighboring countries. This is especially facilitated by the porosity of the borders, the presence of co-ethnics and the remoteness of these regions.

- The increasing engagement of armed groups in criminality, especially extortion2 and targeted killings.

- The distinctiveness of the process of armed insurrection and its interconnections with structural causes of conflict. These structural drivers include attempted imposition of modern land tenure systems on traditional forms of land tenure, the inequities of development processes in areas populated by ethnic minorities and an opaque legal regime that has arisen due to the functioning of the Armed Forces Special Powers Act.3

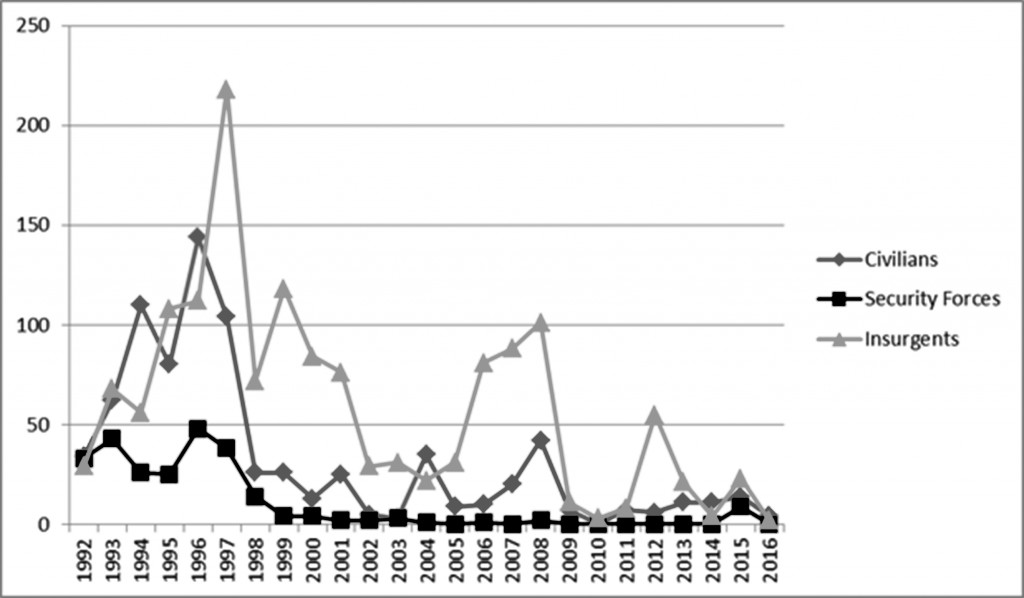

In terms of overall violence, the declining violence in Nagaland is extremely important, for it can be substantively attributed to the current ceasefire arrangements which will be discussed subsequently. In terms of absolute numbers of fatalities the following graph shows the trends of violence experienced in the state since 1992.

According to the South Asia Terrorism Portal, 2,531 persons have been killed in violence in the state.4 The number of injury victims and those missing are not known.

The maintenance of organisational integrity of the NSCN (IM) and NSCN (Khaplang) under the current ceasefire arrangements in Nagaland has meant a degree of ambiguity…

One of the most important aspects of examining trends of violence in the Northeastern region and Nagaland in particular is the interdependency problem. The Naga armed movements have a critical role in fueling the conflict, as they not only function in Nagaland but also in the adjoining states of Manipur, Assam, Arunachal in addition to being active in Myanmar. Although, it can be argued that their networks are much broader than the areas mentioned, for our purposes we seek to focus on the most important and militarily the most powerful armed movement the NSCN (IM).

It is imperative to point out that the history of the Naga armed movements’ struggles for autonomy and secession has been extensively studied and our focus is on the current situation. Currently, the Naga peace process functions at two levels; the first, is the formal channels of ceasefires and negotiations between the Government of India and the NSCN (IM) and the NSCN (Khaplang). The second, is the informal peace process initiated by civil society organisations under the banner of the Forum of Naga Reconciliation (FNR) in order to maintain peace between both the factions. Moreover, with the emergence of the NSCN (United) and the NSCN (Khole-Khitovi) inter-factional struggles have become a threat to stability in the Naga-dominated areas of the Northeastern region. The total number of cadres killed in factional struggles in areas of Nagaland and beyond is seen below.

Casualties of Factional Struggles in Nagaland and adjoining areas6

| Years | Killed | Injured |

| 2003 | 14 | 0 |

| 2004 | 27 | 12 |

| 2005 | 30 | 6 |

| 2006 | 74 | 34 |

| 2007 | 90 | 36 |

| 2008 | 119 | 14 |

| 2009 | 21 | 12 |

| 2010 | 8 | 2 |

| 2011 | 49 | 13 |

| 2012 | 20 | 15 |

| Total | 452 | 144 |

Rationale for Case Selection and Methodology: The Importance of NSCN (IM)

The NSCN (IM) which was formed in 1988, under the leadership of Isak Chisi Swu and Th. Muivah, are proponents of the idea of Greater Nagalim. The idea of greater Nagalim propounded by the NSCN (IM) is both an ideational and territorial concept. As seen below Greater Nagalim in the NSCN (IM)’s view consists of the following:

Nagaland (Nagalim) has always been a sovereign nation occupying a compact area of 120,000 sq.km of the Patkai Range in between the longitude 93°E and 97°E and the latitude 23.5°N and 28.3°N. It lies at the tri-junction of China, India and Burma. Nagalim, without the knowledge and consent of the Naga people, was apportioned between India and Burma after their respective declaration of independence. The part, which India illegally claims, is sub-divided and placed under four different administrative units, viz. the states of Assam, Arunachal Pradesh, Manipur and Nagaland. The Eastern part, which Burma unlawfully claims, is placed under two administrative units, viz. Kachin State and Sagaing Division (formerly known as the Naga Hills). Nagalim, however, transcends all these arbitrary demarcations of boundary.7

While Nagalim is seen as an idea that is to be realised, the actuality of the idea is distinct in its form…

This vision of Nagalim also coincides with the areas in which the organisation functions militarily. At the same time the NSCN (IM) is unique because under the current ceasefire arrangements, especially since 2004, the NSCN (IM) is not considered a banned armed outfit, but rather as a political movement.

This balance between the political and military aims of the movement can be seen in the membership being granted to the NSCN (IM) in the Unrepresented Nations People’s Organisation in 1993, and its presence at the United Nations Conference on Indigenous People in 1994. The concept of Nagalim has meant an increasing level of activity in the surrounding states; a level of activity, which is highly localised and remains unexamined. Increasingly, this micro-level activity also impinges on the territorial and ‘national’ aspirations of other ethnic groups. In the case of Manipur, the presence of the various factions of the NSCN has meant confrontations with Kuki groups and others.8 The following table shows the activities of Naga-groups (all factions of the NSCN) which were active in Manipur between 2008 and 2009.

Table 1: Activity of Naga Armed Factions in Manipur: 2008-20099

| Date of Incident | Summary of Incident |

| 16/9/08 | Abduction and release of members of one armed group by another |

| 28/9/08 | Arrest |

| 4/2/2008 | Arrest |

| 13/11/08 | Arrest |

| 2/12/2008 | Arrest/extortion related |

| 10/2/2008 | Arrest/Extortion related |

| 15/2/09 | Arrest and recovery of explosives |

| 18/2/09 | Armed clash between three groups, 4 suspected cadres killed, 3 injured |

| 30/3/09 | Armed clash between two groups, one suspected cadre killed and two injured |

| 31/3/2009 | Armed clash between two groups, one suspected cadre killed, two injured |

| 1/5/2009 | Gunfight reported between suspected cadres and Army patrol, unconfirmed casualties |

| 10/5/2009 | Armed clash between two groups, 3 villagers reported taken hostage |

| 28/2/08 | Gunfight between Assam Rifles and NSCN-K |

| 12/8/2009 | Encounter/Death |

| 26/8/09 | Assault and injury of NRHM campaigners by suspected cadres |

| 15/9/09 | Assault and injury of surveyors of Union Ministry of Health and Family Welfare |

| 23/9/09 | Killing of suspected cadre by unknown, sharp weapon injury on body |

| 28/9/09 | Arrest |

| 19/10/09 | Armed clash between two groups, killing of 2 suspected cadres |

| 20/10/09 | Arrest |

| 15/11/09 | Arrest/extortion related |

| 7/1/2008 | Abduction of businessman and van driver |

| 20/3/08 | Arrest |

| 26/3/08 | Armed clash between two armed groups |

| 30/3/08 | Arrest |

| 8/1/2008 | Attack on Army Personnel |

| 10/4/2008 | Armed clash between rival factions of NSCN, killing of 1 cadre |

| 10/4/2008 | Armed clash between rival factions, gun battle 9:00am-3:00pm |

| 11/4/2008 | Armed clash between rival factions, killing of 3 cadre |

| 14/4/08 | Armed clash between rival factions of NSCN |

| 11/1/2008 | Bomb blast in field, four civilian children wounded |

| 22/4/08 | Arrest |

| 9/5/2008 | Closure of Deputy Commissioner Senapati offices, NSCN/GPRN diktat |

| 14/1/08 | Surrender of NNC cadre to NSCN(IM) |

| 8/6/2008 | Encounter/Death |

| 8/6/2008 | Arrest |

| 11/6/2008 | Arrest |

| 29/7/08 | Surrender of suspected cadres to Assam Rifles |

The maintenance of organisational integrity of the NSCN (IM) and NSCN (Khaplang) under the current ceasefire arrangements in Nagaland has meant a degree of ambiguity, in the relationship between the Naga armed factions and the state governments especially of Manipur and Arunachal.

The de facto presence of the NSCN factions is more than just an issue of politics. Indeed, there also is a presence in terms of ideas, ideology and discourse. The pamphlets produced by the Government of the Peoples’ Republic of Nagaland-GPRN (and directly linked to the NSCN-IM) which were collected in Ukhrul District of Manipur in November 2010, might not be considered as “literature” in the true sense of the word. Yet, these pamphlets provide us an insight into the world view of the movement, the perspectives and biographical aspects of the main leaders, the aspirations of its ordinary members, the manner in which an abstract idea of Nagalim is actually seen as existing as a given reality.

The series of pamphlets titled “Nagalim Voice: A Monthly News Bulletin” (published by the GPRN) covers the months of May 2008, September 2008, November 2008 and December 2008.

Fresh recruits from every nook and corner of Nagalim are endlessly streaming to the Mt. Gilead Training Centre to enroll themselves as soldiers of Naga Army…

Analysis: Thematic Findings from the Nagalim Voice

Some of the major findings after examination of these sources require detailed description. Using qualitative content analysis, we thus provide examples of the broader themes that were observed in the pamphlets, and substantiate them with actual extracts.

- Perspectives on Naga Nationalism in Relation to Nagalim

One of the most interesting aspects of the pamphlets was the manner in which Nagalim was viewed as an existing reality. Moreover, this notion of nationalism is generated from the leadership. As seen in a speech of 20 January 2005 at Camp Hebron, reproduced in the December 2008 edition, outlining the basic principles Isaac Chisi Swu states, “The Naga people without Nagalim is a Homeless Nation.”10 However, the struggle for this claim is not finite, and will continue until it is realised. Thus, in the September 2008 bulletin Isak Chisi Swu is quoted as saying, “The journey to our promised land is never too long. We will certainly reach one day, because we have been destined to reach and live there to glorify a living God.”11 While Nagalim is seen as an idea that is to be realised, the actuality of the idea is distinct in its form. It is not a nationalism just based on territorial claims. Identity and religion also play an important role.

This vision of nationalism which combines territoriality with religion is constantly reiterated in the pamphlets. Thus, for instance, reporting on a passing out ceremony of the 7th Batch “Naga Army” at Mt. Gilead Training Centre reported in the May 2008, the pamphlet stated, “Brigadier J. [name withheld by authors], GSO (Administration) the Guest of Honour said, “The nation’s principle should always be the priority and no other interest should come in between, and that way you will save the nation.” He also encouraged the young Naga army personnel to have a vision with focus on Christ and the nation. While pointing out the importance of discipline in the Army, he said “Loyalty to the nation is loyalty to God and therefore, you must know your duty.12

The territorial and religious aspect of Nagalim, also facilitates connections with co-ethnics in Myanmar. Indeed, the pamphlets envisage Nagalim to include, Naga territory in Myanmar, which is referred to as Eastern Nagalim. Thus centrality of religion in the appeal of the GPRN is seen in an article, which describes the work of the Council of Nagalim Churches in Eastern Nagalim. According to the article, “the Naga National Workers” could only enter into Eastern Nagalim in the 1970s and subsequently engage in spreading Christianity in the region.13 The abstract idea of Nagalim is moreover closely related to the shaping of the movement’s identity, especially when seen in relation to negotiations with the Government of India.

Another interesting aspect of the organisational life is the role of women who constitute the Ladies Unit of the Naga Army…

- “Nationalism” and the Current Peace Process

This territorial/religious vision of Nagalim, has led the NSCN (IM) to engage in a balancing act vis-à-vis the Indian state and the ongoing peace process. Thus for instance opposition to integration with the Indian state is a core principle of the NSCN (IM). Commenting on India’s Look East policy Isaak Chisi Swu states, “History has taught us that any policy framed by Delhi for Nagalim in particular and the Himalayan region in general cannot be but viewed with revulsion.”14 Moreover, “the real motive of India Look East policy is to militarise the region with the strategic cooperation of the Burmese Military Junta to crush the revolution. New Delhi wants our land and resources for its economic development and also trade relations with others, but it is for sure, they didn’t want the people. The policy is not only going to cause environmental devastation and economic disaster, but it will definitely widen the gap between the ‘haves’ and ‘have-nots.’ As such, the right of the people for justice and democracy is deliberately and brutally suppressed.”15 At the same time, despite the seemingly deep opposition to the concept of India, the pamphlets do convey the movement’s recognition of the negotiation process, as central to solving the Indo-Naga dispute. The principle underlying the negotiations in the view of the leadership is “freedom” which is left undefined in a speech by Isak Chisi Swu in the December 2008 edition, “Freedom was too dear to part with because it is freedom that makes our existence more meaningful. That freedom is ours so long as we hold fast to it above everything else. We have never lost faith in our people – your strength, your wisdom and your resources. Credit must go to the elders who awakened our spirit of Naga nationalism in each and every one of us so that we can hold Nagalim tight to her bosom and protect our freedom. No settlement can be entered into without taking the opinion of the Nagas. We will negotiate on the basis and spirit of our natural rights and our unique history.”16

Moreover, in the same speech he states, “The claim of a people to nationhood, it cannot be denied that a free Nation could only be established through conscious effort of the people concerned. Just as our fighting is principle based, so also our negotiation is principle based. Any solution that betrays the principle is not a solution at all. Re-assure that the NSCN will never into any agreement against the will of the Naga people nor will it take a decision at the expense of the rights of the Naga people.17

While the formal peace process is seemingly targeting tangible political goals in terms of violence reduction, a speech by Isaak Chisi Swu in the September 2008 edition indicates that for the movement the objectives for which they negotiate are in many ways intangible. Thus, for instance, he states, “Nagalim is based on three God gifted things-land, freedom and eternal salvation under which Naga’s political foundation was laid down. Therefore, it is a matter of every Naga to exercise their duty to defend the land given by God, and this is why the long process of Naga’s talk with the Government of India is still going on because it is a matter of finding an honourable settlement.18

This abstract objective of settlement is further reflected in an autobiographical account by Isak Chisi Swu in the December 2008 issue, “We have withstood trials and ordeals many a time. We know that crisis of any sort is no stranger to the revolutionary people. Be it informed that the solution will come neither come from the East nor the West, it will come only from a firm stand for the principle and for me, the chosen banner is Nagalim for Christ.19

The NSCN (IM) as an armed movement occupies an important space in the politics of the Northeast…

- Perspective on Inter-Factional Rivalry

It is clear from the pamphlet that from the standpoint of the movement the problem of factionalism cannot be ignored. The pamphlets convey that the NSCN (IM)/ GPRN sees itself as the sole and legitimate upholder of the concept of Nagalim. While the ceasefire with the Government of India has meant a reduction in military engagements with the central and state security forces, there has been no reduction in factional struggles among the Naga groups. Outlining the vision for a peaceful Nagalim, the editorial column of the November 2008 issue holds the India and Myanmarese governments as responsible, “Ever since the declaration of Naga independence on 14 August 1947, the travails of life for the Nagas is a living testimony of resistance against the oppression and occupation by the Indian and Burmese armed forces. But Nagas have a dream all this will come to an end. We have a dream that a day will come when India will stop playing “divide and rule” policy against the Nagas, instigating one group against another and one tribe against another. We have a dream that the end of bloodshed and killing among the Nagas will come soon and the dream of true reconciliation and unity will be seen in reality.”20

In the December 2008 issue, Isak Chisi Swu reaffirms the NSCN (IM) as being the main proponent of the Naga cause, “Everyone, friend and foe, knows well that the case of the Nagas is unique and NSCN represents the issue. Realising the futility of solving the political problem through military means, Indian leadership sent feelers to us for political dialogue. They too understand well that Khaplang or NNC do not represent the issue. Dead organisations and wrong leadership cannot represent the Naga people. People from some quarters claimed India has stopped killing Nagas, but this defies ground realities. The enemy is still killing Nagas through the person of Nagas. Stooges thus created are many, working at the behest of the India to indulge in all variety of counter-revolution activities, sabotage, desertion and indiscriminate killing. The enemies have invaded and occupied the mind of many Nagas. The desertion of Azheto and party is another coup attempt engineered and financed by enemies.”21

At the same time, other factions are condemned for engaging in armed action or for opposing the aims of the group. As stated in the May 2008 issue, “The Azheto-Mulatano-Kitovi marauding members attack NSCN posts on a number of occasions. But victory they never take home, only their coffins are collected. A shattering and demoralising blow for the misadventures against the NSCN, and the Naga people. The blood of innocent civilians and the tears of fatherless children and their widowed wives at the hands of this blood thirsty group is a sin against the Naga nation and in the eyes of God, it is abominable crime that wouldn’t escape his wrath.”22

Lastly, another example is seen in an article called “Confessions of Home Comers.” Describing the return of two former members who had defected to the NSCN (K), the article which appears in September 2008 stated, “They felt betrayed and cheated on the issue of unification as initiated by Azheto Chophy. No policy was scrutinised and thus, no transparency in the workings of the group. When Azheto’s unification group was officially merged with K-group without any consultation, they felt the earth moving away from their feats, shattering all their hope to see Naga unification. For the sake of the Naga nation they still believe but with the confession to be made before the Naga people they find their way back to Hebron to tell the story of their folly. They were disgusted with the style of functioning where the organisation structure hardly exists, forget about the GPRN (of NSCN-K) they are so obsessed with. No political vision and no political system to pull the people together for common political interests. Worst of all, they find dejected persons occupying high decorated position, but given no voice in the running of the party.”23

- Organisational Life

Having examined the views of nationalism, the peace process and perspectives on factionalism, it is important to highlight some examples of the organisational life of the movement. The pamphlets clearly indicate the centrality of the idea of a “Naga Army” in the overall organisational structure of the movement. The pamphlets carry photos of Camp Hebron (the main NSCN-IM designated camp in Dimapur) as well as those of the Mount Gilead Training Centre (unspecified location). Talking about the 8th Batch of the Naga Army which was undergoing training at Mount Gilead the November 2008 issue of the pamphlet states, “In keeping with the revolutionary spirit of eternal vigilance, recruitment in the Naga Army is a continuing process. Fresh recruits from every nook and corner of Nagalim are endlessly streaming to the Mt. Gilead Training Centre to enroll themselves as soldiers of Naga Army. Setting the standard the NSCN training centre is emerging as the best among the revolutionary groups in the Indian subcontinent.”24

Members of the “Naga Army” are encouraged to uphold values of discipline and good behavior. An unnamed official advises revolutionaries in the Soldier’s Honor section of the November 2008 issue, “Once you have taken the plunge to be part of the revolutionary movement, the first and foremost duty is to prove your worth as a role model, and set standards for others to follow. Let your actions and behavior send influential messages to your superiors and to your subordinates. Respect is important in social set up. But it is more critically felt in the revolutionary set up. Though respect is one of the key revolutionary disciplines, earning respect from others is more worthy than demanding.”25

Another interesting aspect of the organisational life is the role of women who constitute the Ladies Unit of the Naga Army. Describing the role of the Ladies Unit in a section called “Shouldering Equal Responsibility” the September 2008 issue states, “The Naga Army is the vanguard of the Naga nation, and its responsibility to keep the hope of the Nagas alive is the everyday task, no matter what comes. But in the grueling journey of more than 60 years, the Ladies Unit of Naga Army are not far behind in proving themselves equal to the task-be it in the battle front or any that matters in defending the nations interests. The traditional role of the ladies in the Army is more colourfully seen in the Naga Army than anywhere else. The situation is different in Nagalim and so is the demand of the situation that motivated the ladies. The Commander of the Ladies Unit (name withheld) exuded full confidence with her cadres, for they have shown their worth in different fields – battlefield, medical, church and industries. In keeping with today’s information technology the ladies work hand in hand with the boys in computerising the office management. Data processing and internet browsing to keep abreast of the daily events across the world is the other works that keep the ladies busy. Normally ladies are given four years of service before shifting to marriage life. But it has been observed that the charm of the national service is so captivating that “marriage” is hardly a factor.”26

Apart from the military activities, the pamphlets also provide testimony, to the role of outreach and advocacy, in the movement’s goals. The examples from the September 2008 issue gives evidence of the types of activities undertaken by the movement that would be similar to civil-“military” relations. Some of these activities undertaken in that month are listed below.27

- Reconciliation meeting at Auvuto Baptist Missionary Centre, Dimapur (9th September) under the Forum for Naga Reconciliation.

- Visit of delegation of Naga Student Federation (NSF) on 8th September to Camp Hebron, under the banner of “a journey of common hope.”

- Naga Christian Forum, Senapati, consisting of 31 pastors, visit Camp Hebron on 13 September 2008.

- One day consultative meeting with NSCN members (an initiative of Kuknalim Foundation Kohima) at Hebron on 13 September 2008 supported by the State AIDS Control Society.

Conclusion

The article has provided an overview of four pamphlets published by the GPRN/NSCN (IM). An attempt was made to use these sources to provide some insights regarding the worldview of the movement. While extracts from the sources reveal the linkages between the broader political context and the type of discourse emanating from the movement, certain aspects of this connection require reflection. The article in its essence is limited by the lack of continuity in the sources. This constraint arises out of the nature of conducting such kind of research. The aims and objectives of armed movements are extremely difficult to discern.

This partly arises out the constant changing of the political aims and the shifts in the attendant military capabilities to achieve the aims. The NSCN (IM) as an armed movement occupies an important space in the politics of the Northeast as it is one of the significant secessionist groups that is adhering to ceasefire arrangements with the Government of India. The maintenance of organisational integrity is one of the anomalies of the peace process, and in many ways, the peace process is paving the way for the increasing acceptance of the idea of Nagalim for members of the movement.

One of the more significant aspects of the sources, is that they convey the manner by which the GPRN/NSCN(IM) see themselves as “sovereign” and exercising certain degrees of governance. That the limiting of the “Naga Army” to specific designated camps in Nagaland, is one of the solutions, designed for the conditions of that specific conflict; yet, there is a great deal of ambiguity surrounding the functioning of the NSCN (IM) and its claim to Nagalim outside the borders of Nagaland.

While peace in Nagaland is viewed as a reduction in violence in absolute numerical terms in the state, it does not necessarily mean a reduction in armed activity in adjoining regions by the group. The literature emanating from armed movements in the Northeastern region requires thorough study and analysis if solutions towards peace are to be found. Simply interpreting armed movements as military and political entities implies a serious oversight. Rather, armed movements must be situated in their sociological context, as organisations that shape worldviews, entities that generate norms of behaviour that lead to unique cultural practices and identities, and eventually dictate the life-choices of their adherents. In conclusion, three areas of immediate research require mention if we are to systematically study armed movements. First, there is a need to document and consolidate diverse sources of literature, including the press releases by armed movements that appear in local newspapers. Second, micro-level studies at the local level which involve testimonies from current and former members of movements are required, in order to substantiate findings from the analyses of the “literature” that these movements produce. Lastly, these consolidated findings must be incorporated into peace-building efforts designed to mitigate the structural causes of conflict, versus the obvious political solutions.

Notes and References

1. Bethany Lacina, “The Problem of Political Stability in Northeast India: Local Ethnic Autocracy and the Rule of Law.” Asian Survey XLIX No. 6(2009): 998-1020. This is also seen in our data whereby security forces fatalities and injuries as much lower compared to those of civilians and armed groups.

2. Interview with anonymous police official, November 2010.

3. Government of India, Report of the Committee to Review the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act, 1958 (New Delhi: Ministry of Home Affairs, 2005)

4. South Asia Terrorism Portal (http://www.satp.org/satporgtp/countries/india/states/nagaland/data_sheets/insurgency_related_killings.htm)

5. Ibid. (Accessed September 6, 2012).

6. Veronica Khangchian, “Naga Factionalism Escalates,” South Asia Intelligence Review http://www.satp.org/satporgtp/sair/Archives/sair10/10_41.htm#assessment2> (Accessed September 4, 2012).

7. Sanjib Baruah, ”Confronting Constructionism: Ending India’s Naga War,” Journal of Peace Research 40, no. 3 (2003):324.

8. Vibha J. Patel, “Naga and Kuki: Who is to blame,” Economic and Political Weekly 29, no. 22 (1994):1331-1332.

9. Unpublished Database, “Manipur Micro-level Insurgency Database 2008-2009,” Centre for Study of Political Violence, Jindal School of International Affairs (2012).

10. Government of the Peoples’ Republic of Nagaland, Nagalim Voice Volume II/Issue 017, September 2008, p. 1.

11. Ibid.

12. Government of the Peoples’ Republic of Nagalim, Nagalim Voice Volume II/Issue 05, April-May 2008, p. 5.

13. Government of the Peoples’ Republic of Nagalim, Nagalim Voice Volume II/Issue 018, November 2008, p. 5.

14. Government of the Peoples’ Republic of Nagalim, Nagalim Voice Volume II/Issue 05, April-May 2008, p. 4.

15. Ibid.

16. Government of the Peoples’ Republic of Nagalim, Nagalim Voice Volume II/Issue 019, December 2008, p. 2.

17. Ibid.

18. Government of the Peoples’ Republic of Nagalim, Nagalim Voice Volume II/Issue 017, September 2008, p. 1.

19. Government of the Peoples’ Republic of Nagalim, Nagalim Voice Volume II/Issue 019, December 2008, p. 6.

20. Government of the Peoples’ Republic of Nagalim, Nagalim Voice Volume II/Issue 018, November 2008, p. 2.

21. Government of the Peoples’ Republic of Nagalim, Nagalim Voice Volume II/Issue 019, December 2008, p. 6.

22. Government of the Peoples’ Republic of Nagalim, Nagalim Voice Volume II/Issue 05, April-May 2008, p. 2.

23. Government of the Peoples’ Republic of Nagalim, Nagalim Voice Volume II/Issue 017, September 2008, p. 6.

24. Government of the Peoples’ Republic of Nagalim, Nagalim Voice Volume II/Issue 018, November 2008, p. 2.

25. Ibid, p. 6.

26. Government of the Peoples’ Republic of Nagalim, Nagalim Voice Volume II/Issue 017, September 2008, p. 3.

27. Ibid, p. 5.