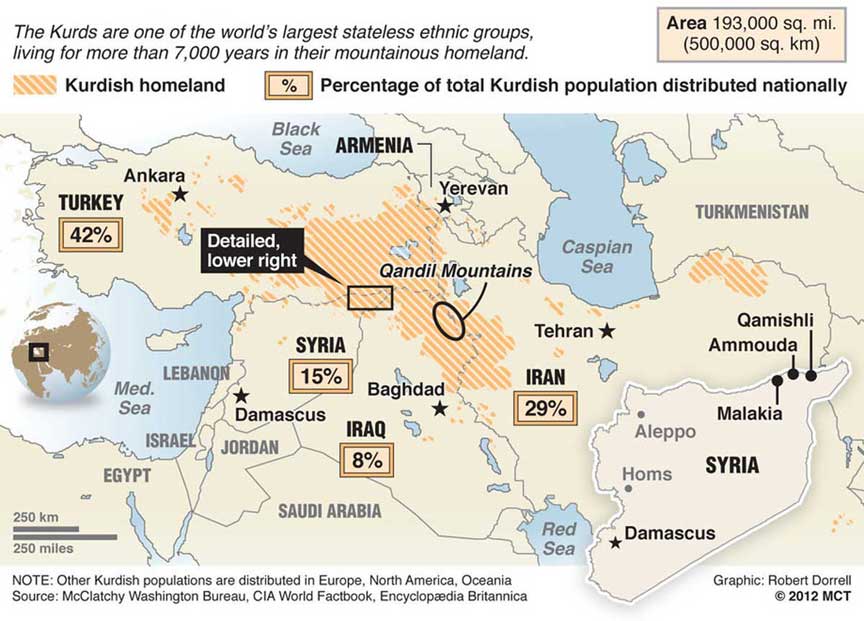

The 30 million or so Kurds are large ethnic minorities in Turkey, Syria, Iraq and Iran, but have no sovereign state of their own. This status quo is a continuing source of instability in the region, and a recurring theme throughout the 20th century was the significant conflicts between the various Kurdish populations and their de facto governments. Kurdish nationalists of the PKK (Kurdistan Workers‟ Party) have fought a long-running guerrilla war against the Turkish government, Iraqi Kurds have fought many conflicts with the Saddam regime in Iraq, and Syrian Kurds are currently major combatants in the Syrian Civil War. This is a multifaceted issue, with overarching principles such as the right to self- determination and national sovereignty at stake, as well as more practical issues such as refugee crises and self-government.

Kurds have played a central role in the reconstruction of Iraq, and have secured considerable rights and safeguards from the central government.

The situation is made more complex by the differences in political representation and status of Kurds in the various countries, with discussions and working papers having to reference and consider the differences between the various regions. The events discussed are very current – there are active negotiations in Turkey, shifting political dynamics in Iraq, and an on-going civil war in Syria, and a postponed pan-Kurdish conference.

History

The Kurdish people have lived in the upper reaches of the Euphrates and Eastern Anatolia for thousands of years. While their exact origins are unclear, with some sources suggesting the existence of a group of people closely related to Persians fighting the Sassanid Empire in the 4th century AD. References to Kurds and Kurdish states were relatively few, but sources attest that independent Kurdish principalities were established in eastern Anatolia and northern Mesopotamia starting from the 10th century, many of these surviving well into the 15th before being conquered by the Ottoman Empire.

The height of Kurdish power and influence came in the 12th century, when, under the leadership of Nur-al-Din and Saladin, they defeated several crusades (most famously Richard the Lionheart’s Third Crusade), crushed the Crusader states, and established the Ayyubid dynasty. This dynasty would rule much of the Middle East until Mamluk revolts in Egypt in the 13th century, and the Mongol invasions of the 13th and 14th century. While the Kurds, as a people, have had a long, rich history, modern Kurdish nationalism dates back to the 19th century, where growing national awareness gave rise to dreams of an independent Kurdistan. Several attempts were suppressed by the ruling Ottoman Empire with particularly brutal efficiency.

Most of what is now Kurdistan was within the borders of the Ottoman Empire, with particularly large populations in Eastern Anatolia. In the aftermath of the First World War, the Entente initially attempted to carve out a Kurdish state from the ruins of the Ottoman Empire during the Treaty of Sevres. However, the Turkish victory in the War of Turkish Independence tore out a large chunk of the proposed state (now the Turkish portion of Kurdistan), and the other regions were instead absorbed into the French mandate of Syria and British mandate of Iraq. From then, Kurdish history diverged, as the various ruling governments took differing approaches to their Kurdish minorities, and therefore they will be treated individually.

Some Kurds want nothing less than a pan- Kurdish state to be carved out from Syria, Iraq, Iran and Turkey, while other Kurds wish for more autonomy and for their rights to be recognized.

Kurds in Iraq

During Iraq’s early years, a combination of weak central governance from Baghdad and continuing British interference meant the Kurds were granted considerable autonomy, and were able to run much of their own affairs and have their own laws. The post-Second World War withdrawal of British troops and the rise of a pan-Arab identity as the 20th century progressed meant successive governments began restricting and limiting Kurdish autonomy and rights. Kurds rose up several times against the Iraqi government, especially in 1963. In all these cases, the rebellions were brutally suppressed.

The suppression reached a pinnacle in the 1980s, where during the Iran-Iraq War; Saddam Hussein’s ruling Baathist party viewed the Kurds as potential traitors, due to their ethnic differences and propensity to revolt against the central government. The Iraqi military engaged in brutal campaigns against Kurdish independence movements and, on multiple occasions, used chemical weapons on Kurdish cities.

The First Gulf war saw drastic improvements in the Kurdish political position, and considerable autonomy was granted to Iraq’s Kurdish provinces as part of the peace agreement. UNSC Resolution 688 saw the enforcement of a no-fly zone over most of Northern Iraq, in order to stop further crackdowns and bombings from Baghdad. A three year civil war, however, soon emerged where rival Kurdish factions, the Kurdish Democratic Party and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan fought each other in a three year civil war, before Turkish intervention prompted an armistice and eventual reconciliation. Kurds played a significant role during Operation Iraqi Freedom, helping the American-led coalition to secure much of northern Iraq. Kurds have played a central role in the reconstruction of Iraq, and have secured considerable rights and safeguards from the central government.

While there are still considerable political divides between the central Iraqi government and the Kurds, Iraqi Kurdistan is the best example of a successful and peaceful Kurdish region. Even during the worst of the Iraqi insurgency, terrorism in the northeast was rare, with Kurds mostly responsible for their own internal security, and key allies of the coalition during American counter-insurgency operations in the unstable Sunni Northwest. Helped by oil wealth, the region is growing increasingly prosperous, assertive and is a prime example of a stable Kurdish proto-state. The Iraqi Kurds are even getting along with Turkey – their new-found oil wealth and common interests (particularly their mistrust of Iran, and pro-Iranian elements in the Iraqi government) have made Turkish companies big investors in Iraqi Kurdistan, with trade booming – Iraqi Kurdistan looks set to displace Germany as Turkey’s biggest trading partner.

Syria has the smallest Kurdish population of the major countries in the region, but, is also the most current issue.

Kurds in Syria

The history of Kurds in Syria is similar to those of Kurds in Iraq. Initially granted considerable autonomy by the French colonial authorities, the Syrian Kurds found their minority rights and autonomy increasingly restricted by the pan-Arab nationalist governments that came to dominate Syria in the 1950s and 60s, particularly during the years of Syria’s political union with Egypt. The Kurdish language was, and still is, legally banned in Syria, and Kurdish culture is generally suppressed. Many Kurds were also stripped of their citizenship in the 1960s, entailing loss of political and property rights.

Throughout the rest of the 20th century, Kurds were often displaced from their homes by Syrian policies encouraging Arab settlement in predominantly-Kurdish areas, alongside repression of Kurdish culture and languages. Crackdowns and disappearances of particularly outspoken individuals were common, and Kurds were marginalized and ostracized by the central government in Damascus. In a sudden reversal of previous policy, however, in 2011, Syrian Kurds were granted a degree of limited autonomy by the Assad regime, and repressions were eased, with many Kurds stripped of their citizenship in the 60s offered Syrian citizenship again (according to some, this was done cynically, to destabilise the Turkish-PK peace process). The Syrian Civil War, however, has disrupted central government control over Kurdish regions.

Kurds in Turkey

The Kurds are the dominant ethnic group in Eastern Anatolia (though, due to migration, Kurdish pockets exist throughout all of Turkey), and form up to a fifth of the population of Turkey, though the exact proportion of the population is uncertain. While ostensibly protected and treated equally to Turks in the constitution, throughout the 20th century, many Turkish governments have attempted to force Kurds to assimilate more closely into Turkish society – a stance long resisted by the Kurds. Indeed, Turkish non -recognition of Kurdish cultural and linguistic rights is a major barrier to Turkish accession to the European Union, a long-term goal of successive Turkish governments, as these policies violate several EU requirements on minority rights. There were many revolts against Turkish rule throughout the 20th century, but the longest- running revolt has been waged, with interruptions, since 1984 by the PKK (Kurdistan Workers Party). This is a particularly controversial organization, with communist-leanings, that has been classified by Turkey, the EU, the US and NATO as a terrorist organization.

There is also a growing refugee crisis, as Kurds fleeing from the civil war will attempt to cross the border into more ―stable regions such as Iraqi or Turkish Kurdistan.

Kurds are not united behind the PKK, with significant numbers of Kurds wishing to remain part of Turkey, and forming a large part of many pro-Turkish paramilitaries (called ―Village Guards) created by the Turkish Army to fight the PKK in the Kurdish southeast. The conflict itself caused significant devastation to South-eastern Turkey, particularly the countryside, with mass Kurdish migration (and forced removal by the Turkish Army) to larger urban areas. The PKK has also operated from relative safe havens in Iraqi Kurdistan, particularly since the First Gulf War, and, on several occasions, Turkey has sent military forces directly into Kurdish territory – first, in 1996, as an intervention force in the Kurdish civil war, and, in a more limited fashion, throughout the 2000s against PKK groups. However, since then, Iraqi Kurdistan and Turkey have found common cause in many matters – primarily economic, but also political – both have reservations about Iraqi Prime Minister al-Maliki and his close ties to Iran.

A long, tortuous peace process between Turkish Kurds and the government has been in the works for many years. Many ceasefires have been declared – the longest was a unilateral ceasefire declared by the PKK in 1999 was rescinded in 2004, and was then followed by numerous bombings in Ankara and Istanbul, and attacks on military bases across South- eastern Turkey. Further ceasefires were declared, and then broken. 2011-12 was particularly bloody for both sides, with renewed Kurdish attacks on Turkish bases and serious Turkish counterinsurgency operations leading to hundreds of deaths. Recently, however, negotiations have been optimistic – the PKK has toned down its demands from full independence towards cultural recognition, political rights and local autonomy, and have rescinded armed conflict. On December 28th 2012, Turkey announced that it had begun full negotiations with Abdullah Ocalan, jailed founder and leader of the PKK. While many members of the PKK support these talks, there have been conflicts within the PKK, with more militant fighters clashing with those in favour of talks. Pro-Ocalan Kurdish activists, in particular, have been targeted, culminating with a brutal murder of Kurdish activists in Paris.

Kurds in Iran

Unlike Iraqi, Syrian and Turkish Kurdistan, Iranian Kurdistan was never supposed to be part of the post-Ottoman Kurdish state, and had long been under Iranian rule. Iranian Kurds, like Kurds in other countries, have faced cultural repression from the central government in Tehran. Rebellions against the Iranian government have occurred at multiple points throughout the 20th century, particularly the Simko rebellion of 1918-22, which ended with Kurdish leaders being forced into exile by Imperial Iranian forces.

the relative success of neighbouring Iraqi Kurdistan has inspired many Iranian Kurds to speak up and call for greater representation and political rights…

The Kurds had continued conflicts with the Iranian/Persian governments throughout the 20th century. During the Second World War, Iran was occupied by the Soviet Union and the Western Allies, in order to remove a government deemed to be unreliable. The Soviet occupation allowed Kurdish groups in the northwest of Iran to establish a Republic of Kurdistan centred around the town of Mahabad. This received the implicit approval of the Soviets, who viewed them as a potential future ally to help their interests in the region. However, following the Soviet withdrawal from Persia post-war, the Iranian government moved in to crush the fledgling republic and retook control of the region, ending the only independent Kurdish state in recent history. They were enthusiastic supporters of the revolution in 1979, which initially promised to be a liberal revolution to remove the tyrannical Shah, but was quickly dominated by the return of Ayatollah Khomeini and the establishment of a Shi’a Islamic state. Their former revolutionary allies turned on the Kurds, with violent crackdowns on Kurdish towns and villages. Long- running civil unrest caused by elements of Kurdish independence movements continues to this day, while other Kurdish groups have moved on towards more peaceful action.

Unlike in Syria and Turkey, however, Kurdish is a recognized minority language in Iran, and basic Kurdish cultural rights are recognized. However, reports by Amnesty International have highlighted the systematic discrimination against Kurds by the Iranian government, noting that their political, social and economic rights are heavily repressed, and many Iranian Kurds live in poverty. Many are also discriminated against because of their religion – most Kurds are Sunni Muslim, as opposed to the Shi’a theocracy. The relative success of neighbouring Iraqi Kurdistan has inspired many Iranian Kurds to speak up and call for greater representation and political rights, but many of these groups have faced repression and members have often been imprisoned by Iranian authorities and charged with treason.

Discussion of the Problem

The problems faced by Kurds in Iraq are different to those faced by Kurds in Syria, or in Turkey or in Iran. It is important to emphasize that there are many groups with many different objectives – the Kurds do not present a united front with a clear objective. Some Kurds want nothing less than a pan- Kurdish state to be carved out from Syria, Iraq, Iran and Turkey, while other Kurds wish for more autonomy and for their rights to be recognized.

Iraqi Kurdistan officially only consists of 3 provinces in the country’s northeast, but Kurdish inhabited areas stretch well beyond that region.

Iraq

Currently, Kurdish rights in Iraq are very well developed. Kurds are well represented throughout Iraqi politics and society, with Iraq’s ceremonial president, Jalal Talabani, being a Kurd, though recent arguments with the central government in Baghdad, as well as Mr. Talabani’s stroke, have begun to strain relations between the two, with many Kurdish ministers and MPs resigning over a budget considered unfavourable. Iraqi Kurdistan officially only consists of 3 provinces in the country’s northeast, but Kurdish inhabited areas (and indeed, de facto control by the Kurdish Regional Government) stretch well beyond that region. Kirkuk, for example, has a large Kurdish population, but control is currently disputed between the Kurdish regional authorities and the Iraqi federal government.

The Iraqi Kurdish region, however, is viewed as a threat by many of the nations around it – a semi-autonomous Kurdish state is seen by the Syrian government in particular as a potential lightning rod for their own Kurds, Arab Iraqi politicians are resentful of Kurdish demands, and particularly of de facto Kurdish independence – the Kurds even have their own army, the Peshmerga militias, which, while not as lavishly equipped as the American-supplied Iraqi army, still remains a formidable fighting force. Iraqi Kurdistan’s main problem, therefore, is primarily political – the jostling of power between the central government in Baghdad and the Kurdish Regional government in Erbil, and particularly dealing with boundaries and budgets. There is also the elephant in the room – the question of full independence from Baghdad. This possibility may be particularly acute if relations between Kurdish Regional Government and the Iraqi government were to deteriorate further.

Syria

Syria has the smallest Kurdish population of the major countries in the region, but, is also the most current issue. Though initially relatively uninvolved in the Syrian Civil war, Kurds began revolting in 2012. Kurdish militias are engaged in fighting Assad, but there are also growing signs of conflict between generally more secular minded Kurds and more religiously inclined other rebels (particularly al-Qaeda related groups). Currently, the Kurds are in control of the north-eastern, Kurdish-majority area in the country, but recent counteroffensives by the Syrian Army, as well as attacks by other anti-Assad rebels, have made the position more tenuous.

…some groups threatening to halt the on-going withdrawal of Kurdish fighters, due to perceptions that the Turkish government has not made sufficient progress towards safeguarding Kurdish rights.

There is also a growing refugee crisis, as Kurds fleeing from the civil war will attempt to cross the border into more ―stable regions such as Iraqi or Turkish Kurdistan. Iraq received over 40,000 refugees in the first two weeks of August 2013, and this has the potential to accelerate, given the increasing use of brutal chemical weapons and the growing conflicts between the various rebel groups. While other countries have shut their doors to these refugees, they have been welcomed by the Kurds in Iraq. This, however, has the potential to overwhelm the government; even now the Iraqi Kurds are straining under the influx of more refugees than initially imagined.

Further action in Syria would have to look at reconciling Kurdish separatists with the government in power – either the rebels of the Syrian National Army, or, more likely, Assad’s Baathist regime. Again, this will depend heavily on the events of September and October – whether or not a planned American-led intervention goes ahead, or how the civil war will develop. Beyond the civil war, Kurds still face many political obstacles – the victor of the civil war may not necessarily support increased political participation for Kurds, particularly if the victor is Assad, but also, to a lesser extent, if the victors are some of the more extremist Islamic factions.

Turkey

The situation in Turkey is perhaps the most dynamic, as on-going negotiations between the Turkish government and elements of the PKK have yielded dividends. A new ceasefire has been declared in March, and PKK fighters have agreed to disarm and leave Turkey for Iraqi Kurdistan. Talks about legal and constitutional reforms to recognize the Kurdish minority, as well as the Kurdish language and Kurdish culture, have begun. Even now, however, the peace-process is fragile, with many Kurds being unhappy with the pace of change, and some groups threatening to halt the on-going withdrawal of Kurdish fighters, due to perceptions that the Turkish government has not made sufficient progress towards safeguarding Kurdish rights.

Talks on Turkey should focus on the continuing attempts at a lasting peace, particularly at dealing with elements of the PKK and other Kurdish groups dissatisfied with the current arrangements. It should also, however, look into rebuilding South Eastern Turkey, and at cementing the minority rights of Kurds in a multicultural Turkey. South Eastern Turkey has suffered from years of uncertainty and underinvestment due to the continuing conflict, and many towns are full of slums which Kurds fled to during the worst years of the conflict. Kurdish rights would also have to be cemented – Turkey still bans political parties based along ethnic lines, and a Kurdish mayor has faced persecution for wishing a Happy New Year to his constituents in Kurdish, as it violates laws on Turkish being the national language. Steps have been made to launch Kurdish-language TV and radio channels, but these are still controlled by the Turkish state.

Most attempts by the Iranian government to deal with them have been ruthless suppression, rather than negotiation.

As recently as 2009, Turkey jailed Kurdish politicians, particularly prominent Kurdish MP Layla Zena, a former winner of the Sakharov Prize, and banned others from for politics for extended periods of time due to their supposed links to the PKK. Turkey also banned a political party, the Democratic Society Party, with significant numbers of Kurdish politicians. In the 2011 elections, the Democratic Society Party’s successor, the Peace and Democracy Party, boycotted Parliament for several months after several of its MPs were jailed under Turkish anti-terror laws. The full legalization and amnesty for ex-PKK members will likely be a vital part in securing a lasting peace under the peace process.

Iran

Dealing with problems in Iran will mostly concern economic, cultural and political discrimination against the Kurdish people in Iran. . Kurds are underrepresented in Iranian society, with no Kurdish party sitting in the Iranian consultative assembly, partly due to the requirement for candidates to be ―vetted by the Guardian Council. This is a continuing source of instability in certain areas, as many Kurds continue to feel disenfranchised. Armed rebel groups (such as the Party for a Free Life in Kurdistan) persist. Most attempts by the Iranian government to deal with them have been ruthless suppression, rather than negotiation.

Current situation

The Syrian civil war, which began in March 2011, led to an unprecedented exodus of international refugees, including hundreds of thousands of Kurds fleeing to Turkey and northern Iraq. This massive movement presents a problem for Iraq and Turkey. The problem is especially acute for Iraq, where Kurdish-Sunni-Shia’ites sectarian warfare never fully ended after the American withdrawal in December 2011. The civil war has increased Kurdish arming and development of Kurdish militias. Those who have managed to remain in Syria are gaining increasing control of their territory, reducing the influence of the Alawits-dominated government of Bashar al Assad in the east of the country. Fawzia Yusuf, a Kurdish politician spoke for many Kurds when he said ―Our main goal will be to unify Kurdish opinion.

The Kurds are the last military force standing between ISIS and all-out civil war.

The second goal is to form a Kurdish national organization to take charge of diplomacy with the rest of the world. And the third goal is to make decisions on a set of common principles for all the Kurdish people. A prominent effort to unify and organize Kurdish opinion is the organization of a Kurdistan National Conference. Long proposed, major Kurdish political parties are hesitant, worried about antagonizing regional governments. On 4 September 2013, the conference was postponed and rescheduled for 25 November 2013, which is still on hold. The conference might help unify the Kurdish people from all four countries. Taking this step towards unity could ultimately be the starting point towards the unified nation that the Kurds have dreamt of for decades. But disagreements between Kurdish factions make this difficult. Parties are concerned with over representation by some parties while others are insisting on better representation to account for their influence across the region, or even representation overall.

ISIS and the new challenges

ISIS is qualitatively different from the jihadists of the past, who fought against either the ―near enemy of authoritarian Arab regimes or the ―far enemy of the United States and the West. Different from Al-Qaeda, from which it was recently disowned, ISIS heralds a new chapter in the evolution of extreme jihadist. They actively use social networking services such as Twitter, publish financial reports like a profit-seeking company, and release manifestos and narrated videos in fluent English to reach a global audience. Its fighters hail from all over the world, including Europeans, Americans, Central Asians, and even Uyghurs.

While Al-Qaeda recruited foreign fighters to help them in their global jihad against the West, ISIS remains—at least for the time being— firmly focused on sectarian cleansing in Iraq and Syria. It has no qualms about using foreigners as suicide bombers in even minor tactical operations. Years of sectarian policies pursued by the Iraqi government of Nouri Al-Maliki have severely marginalized Iraq’s Sunni community, creating a fertile breeding ground for militancy and insurgency. These groups, which include tribal militias, secular Baathist from the old regime, and radical Sunni Islamists, have a range of grievances against the current government. The battlefield success of ISIS is due to this broad coalition of Sunni groups. Their capture of Mosul, Iraq’s second-largest city, in June set off a major humanitarian crisis as hundreds of thousands of Iraqis of all religious and ethnic backgrounds fled the ISIS onslaught.

Ultimately an independent Iraqi Kurdistan is likely to change not only its own borders, but the entire map of the Middle East.

ISIS and the Kurds

Unlike the Iraqi central government on which the U.S. spent tremendous amounts of money without success, the KRG possesses a more professionalized military, institutional capacity, and political accountability. As ISIS forces approached, thousands of Iraqi troops fled Mosul and other northern cities, leaving behind their American-pro- voided weapons, uniforms, and vehicles, not to mention hundreds of thousands of civilians. However, the professionalism of the peshmerga, the Kurdish military forces, has been in stark contrast to the collapse of the Iraqi army. If ISIS is able to conquer Iraqi Kurdistan, it will only be a matter of time before its forces once again turn to Baghdad and further south, potentially leading to the total breakdown of Iraq as a state. The Kurds are the last military force standing between ISIS and all-out civil war.

Indeed, over the past decade, the Kurds have successfully governed their region even as the rest of Iraq slide into sectarianism and civil war, proudly pointing out that not a single coalition soldier died in Kurdistan during the war, nor was a single foreigner kidnapped. Also, in a part of the world where democracy remains rare, the Kurds strive towards political representation and inclusive government. The people are secular yet religiously tolerant, with Muslims, Christians and many other denominations living side-by- side. In addition, their economic potential is also significant, with estimates that Iraqi Kurdistan could possess up to 45billion barrels of oiling mostly untapped oil fields. To summarise, the success of a viable Kurdistan is thus crucial to the future of Iraq as a whole. Ultimately an independent Iraqi Kurdistan is likely to change not only its own borders, but the entire map of the Middle East.

Chemical weapons used against Kurds by Iraq? Any proof? Can author justify this?

a very insightful article. however, can you dwell upon implications for our

country