Sea Lines of Communications (SLOCs) in the Indian Ocean, came into prominence in the 90s when forces of globalisation sparked a process of huge economic growth that resulted in increased consumption and competitive trade, creating an upsurge in oil demand in both developed nations and developing economies.

Covering an area of 73,556,000 sq kms, the Indian Ocean consisted of some of the most critical sea lanes and choke points that connected the oil rich Middle East, East Asia and Africa with Europe and on which most oil and goods trade came to depend. The ocean became the highway of international trade. It inevitably led to a rivalry between countries for dominance of key trade routes and choke points.

SECURITY OF THE SLOCs

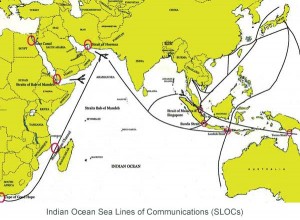

The oceans vast spread hosted heavy international maritime traffic that included half of the worlds container cargo, one third of its bulk cargo and two third of its oil shipment. Its waters carried heavy traffic of petroleum and petroleum products from the oilfields of the Persian Gulf and Indonesia and contained an estimated one third of the worlds offshore oil production. The SLOCs connected major ports through some strategically significant seas and gulfs “” the Persian Gulf; the Red Sea; the Laccadive Sea, between Kerala and the Lakshadweep in the Arabian Sea; the Andaman Sea in the Bay of Bengal, between the Andaman Islands and Burma; the Gulf of Aden at the entrance to the Red Sea and Gulf of Oman at the entrance to the Persian Gulf. In about ten years, between 1985 and 1995, the region saw a jump in cargo and oil traffic by nearly 30%. It was the first sign of the areas growing prominence.

The Navy realised soon enough that to cater to the changed realities, its maritime vision needed to cover the critical areas in the Indian Ocean where our vital national security interests lay. It therefore redrew its area of interests to include the Persian Gulf and the Malacca Strait.

In addition, another phenomenon had a part to play in the Navy’s reworking its priorities power projection. Traditionally, Navies have followed a doctrine of littoral power projection along with the “˜sea control that principally manifested itself in amphibious landings and carrier air power. This changed during the Cold War, when a confrontation between the Soviet and Western navies on the high seas created a “˜blue water emphasis to naval doctrines. The end of the Cold War era, however, saw a return to a littoral priority. The new doctrine proposed a model of “˜power projection in the littorals that meant the deployment of standoff military capabilities to deliver significant force either to deter or coerce. Power projection thus, became the centrepiece of the worlds advanced navies. It became critical for the Indian Navy, to take measures to maintain presence, especially in and around critical SLOCs.

SAFEGUARDING THE SLOCs

Indian Ocean Sea Lines of Communications (SLOCs)

To appreciate the scale of the Navys concerns about safeguarding the SLOCs, it is instructive to consider the sheer expanse and stretch of the area that major Sea Lines of Communications (SLOCs) in the Indian Ocean covered.

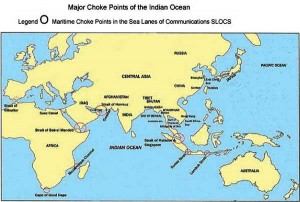

Major Choke Points of the Indian Ocean

Major choke points in the Indian Ocean that conceivably required greater security included:-

- The Strait of Hormuz between the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Oman.

- Bab-el-Mandeb at the southern access to the Red Sea and the Suez Canal.

- The Mozambique Channel between Madagascar and the coast of Africa.

- The Strait of Malacca between Sumatra and Malaysia.

- The Sunda Strait between the Indian Ocean and Borneo.

- The Lombok Strait between the Indian Ocean and the Sulawesi.

THE EMERGENCE OF NEW THREATS

With “˜presence, “˜patrolling and “˜projection, many regional and sub-regional powers thought they had got the power equation right. But, evidently their plans hadnt catered for the twin scourges of piracy and terrorism. The increased maritime activity of the post-globalisation era undoubtedly resulted in economic expansion and development.

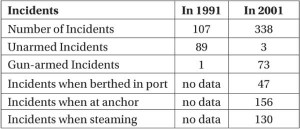

However, despite “˜maritime bonding, this phenomenon strangely, precluded the emergence of a vibrant trans-oceanic community, possibly because wide dissimilarities and divergent interests in regional countries led them to shun each other, but prompted each to pursue economic linkages with Europe and North America. As a result, trade in the SLOCs grew exponentially in value and importance. The high value cargo transiting through its waters was only an invitation for the twin threats of “˜Piracy and “˜Terrorism to raise their ugly heads.Piracy.One of the biggest threats to shipping that emerged in the late 80s was that of Piracy. According to the International Maritime Organisation (IMO) “˜piracy, since the early 90s, posed a threat to shipping of the same scale as it did in medieval ages. 2680 incidents recorded since 1984 (roughly one every third day over the last twenty years), occurred mostly in territorial waters while ships were at anchor or berthed. A steady increase was witnessed in the 90s decade and as statistics show, there was a marked increase in incidents involving firearms.

Soon, it was clear that any disruption in traffic flow through “˜choke points in the Indian Ocean (such as the Straits of Hormuz, Malacca, Lombok and Sunda) could have disastrous consequences. The disruption of energy flows in particular was a considerable security concern for littoral states, as a majority of their energy lifelines are sea-based. Since energy is critical in influencing the geo-political strategies of a nation, any turbulence in its supply would have led to serious security consequences. Given the spiralling demand for energy, it became inevitable for countries to sensitise themselves to the security of the sea lines of communications (SLOCs) and choke points of the region.

Terrorism. Sea Terrorism, in the late 80s was a novel concept, rather too perverse for rational comprehension by national maritime forces that had a linear mind-set. The enormity of the threat that it posed became clear in the 90s, as there was a sudden rush in the number of sea attacks. In 2000, the attack on the American Naval Warship, USS Cole at Aden stunned the world. It was a grim portent of what was to follow in the 9/11 attacks on the USA. Navies reacted by factoring in “˜Terrorism in their plans of operations. But it wasnt an easy exercise as “˜asymmetric warfare was going to take much more time, experience and large-scale coordination to tackle effectively.

THE SPECTRUM OF INCIDENTS

1985: On the 7th of October, four men representing the Palestine Liberation Front took control of the Italian passenger liner Achille Lauro off Egypt. Holding the passengers and crew hostage, they demanded the release of fifty Palestinians in Israeli prisons.

1998: On the 16th of April, the Malaysian tanker Petro Ranger sailed from Singapore bound for Ho Chi Minh City with a cargo of $1.5 million worth of diesel fuel and kerosene. The next day, the agents reported the vessel missing. It transpired that Indonesian hijackers in the South China Sea had seized the vessel. The hijackers held the ships Australian captain at gunpoint for 10 days whilst they transferred more than a third of the cargo to a Chinese-registered vessel. The Chinese Maritime Police intercepted the vessel on 26th April. The hijackers were executed.

The Indian Navy, for the first time began to show signs of increased cooperation with western navies. India and the United States conducted two major, joint naval exercises in the 1990s and a third one in 1996.

1999: MV Alondra Rainbow was hijacked in October 1999 by masked pirates armed with guns and swords. The hijackers were later found to be Indonesian personnel. The ship was rescued by the Indian Navy.

2000: On the 12th of October, the United States Navy Warship, the USS Cole, berthed alongside in Aden was rammed by a terrorist rubber dinghy full of explosives. The attack left seventeen sailors dead and thirty nine injured.

In response to such incidents, the US 5th Fleet was established in 1995, at Bahrain and Kuwait to cover the Indian Ocean, the Persian Gulf, the Arabian Sea and the Red Sea, to monitor the sea lines of communication throughout the region.

In the same year, India and the US signed the “Agreed Minutes on Defence Relations between the US and India” which stated that both sides recognized the importance of enhancing defence cooperation, that the growth of bilateral relations in new areas would be evolutionary and related to convergence on global and regional issues and that enhanced defence cooperation was designed to make a positive contribution to the security and stability of Asia.

The US Defence Secretary visited India that year. Praising the Indian Navys contribution in securing SLOCs, in his address to the National Defence College, he also emphasised his nations shared interest with India in the security and stability of the Persian Gulf region. He reiterated the very strategic basis of the relationship that was based on ensuring the freedom of the seas. It was a fitting testimonial to the Indian Navys approach of securing the SLOCs in the 90s “” through cooperation, collaboration and coordination.

IN RETROSPECT

The Indian Navy, in this decade, realised the increasing significance of safeguarding the SLOCs and made efforts in that direction. By doing so, it sought to further the national strategic interests (of supporting free trade in a growing market economy) and also helped guarantee similar benefits for its littoral neighbours.

Significantly, the Indian Navy, for the first time began to show signs of increased cooperation with western navies. India and the United States conducted two major, joint naval exercises in the 1990s and a third one in 1996. These were the first significant joint naval exercises that India has ever engaged in with a major navy, and helped open the door for similar exercises with other countries. Soon exercises were undertaken with France. By early 2002, it had expanded to include the British and the Singapore Navies.

By the early 90s, the Indian Ocean had a marked central presence in the affairs of the world, not just from an economic but also a military point of view.

The initiative taken in the 90s of cooperation and collaboration not only helped deal effectively with the threats of piracy and terrorism but also aided in the evolution of perspectives that take into account differing perceptions, sensitivities and national interests of the concerned states.

To understand the role of the Navy in the 90s it may be important to review the circumstances in which the Navy was required to operate in that time “” especially with regard to the increased presence of other navies in the region.

By the early 90s, the Indian Ocean had a marked central presence in the affairs of the world, not just from an economic but also a military point of view. Not surprisingly, the region abounded with the presence of many navies. The Indian Navy was a significant force in the Ocean with an expanded sphere of operations. The US, with a base at Diego Garcia and owing to its naval operations in East Asia was also a dominant player. Britain (that formed the British Indian Ocean Territory, way back in the 60s) had since reduced its presence. The French possessed vital territory in the form of some critically positioned islands. The Chinese, the Japanese and other regional navies were also beginning to realise the oceans strategic significance and show interest in the region.

THE UNFOLDING OF EVENTS (1945-80)

The phenomenal rise in interest in the Indian Ocean had its roots in history. The question of its dominance, really, harks back to 1945 when, at the end of the Second World War, a cold war erupted between two powerful countries “” USA and USSR. This confrontation, which was primarily a conflict of competing interests and overlapping ambitions, ended with the dissolution of the latter and Russia emerging as the largest (but militarily weakened) constituent of a new confederation.

In the northern Indian Ocean, India began to be seen as the pivotal regional power and her Navy as the pre-eminent regional Navy. Within the Indian establishment, there was a desire to engage with the US Navy”¦

Throughout the Cold War, the over-riding goal of US policy in the Indian Ocean was to safeguard the supply of Persian Gulf oil to the US and its allies. This was to be achieved by strengthening the Persian Gulf monarchies and sheikhdoms and by positioning forces to deter and counter any Soviet threat from landward to seize the oilfields.

From the 1960s onwards, Britain and the US ensured that as the British Navy withdrew from the Indian Ocean, the American Navy took its place. In the middle of the Indian Ocean, Britain carved out a British Indian Ocean Territory from the Chagos Archipelago to enable Diego Garcia to be leased to the US Navy. The pro-US monarchies in Saudi Arabia and Iran were encouraged to build up their navies.

During the 1970s, the US and Soviet Navies manoeuvred for base and refuelling facilities in the northwest quadrant of the Indian Ocean ”” Berbera in Somalia on the Horn of Africa, Asmara in Ethiopia in the Red Sea, the island of Socotra off South Yemen, Muscat in Oman, and the island of Masirah off Oman. The US started building up Diego Garcia into a naval base. Neither Navy sought facilities from India. Warships of both navies enjoyed goodwill visits to Indian ports.

By the end 1970s, domestic opposition to the US supported Shah of Iran increased to an extent that a revolution was foreseeable. Nearby in Afghanistan, a pro-communist coup was initially successful but soon encountered opposition. Afghan leaders repeatedly sought urgent Soviet military assistance to suppress the opposition.

In anticipation of a Soviet threat to Western oil supplies from landward, the US had started pre-positioning the wherewithal, on board ships, for military intervention in the Persian Gulf from seaward.

Two separate crises coincided in end 1979. The Shah of Iran was overthrown in a coup. Soviet troops entered Afghanistan to assist the protégé government. Despite Soviet assurances that they had no intent to threaten Persian Gulf oil, the US felt it prudent to deploy, on a regular basis, ships from its 7th (Pacific) Fleet to the North Arabian Sea. A new US Central Command, headquartered in the US, was created for this theatre of operations. Whilst events in Afghanistan were still unfolding, the Iran”“Iraq War (1980-1988) erupted. Western navies had to be deployed to escort tanker convoys into and out of the Persian Gulf.

Significantly, this was also a time when relations between India and America showed signs of thawing following a visit by Prime Minister Mr. Rajiv Gandhi to the US in 1985. A rapport developed between him and President Reagan and Indo”“US relations brightened. Successive US Defence Secretaries and US Chiefs of Naval Operations visited India. An Indian Naval Delegation visited the US Navy which was followed by ships visiting each others ports.

DEVELOPMENTS IN THE 90s

In 1990, Iraq invaded Kuwait. In the subsequent operations to evict Iraq, US warships bombarded Iraq from within the Persian Gulf. With bases in nearby Oman and Qatar and an overwhelming presence in the Persian Gulf, the US Navy had established itself in the Indian Ocean. The dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 and the subsequent withdrawal of its Navy from the Indian Ocean further helped its cause.

In the years that followed, turbulence in Afghanistan, a rise in terrorist activities and the lessons that the US learnt in the war against Iraq forced it to review its strategy for the Indian Ocean, but that was in no way an indication of a reduction in presence. To the contrary, it only served to strengthen US resolve to maintain presence in the region.

In the northern Indian Ocean, India began to be seen as the pivotal regional power and her Navy as the pre-eminent regional Navy. Within the Indian establishment, there was a desire to engage with the US Navy that saw some high-level meetings on Confidence Building Measures and culminated with the introduction of the Malabar series of bilateral naval exercises. The exercises, which commenced in 1992, were held again in 1994 and 1995.

In 1995, the US established its Fifth (Indian Ocean) Fleet, headquartered in Bahrain, to conduct operations in the Red Sea, the Arabian Sea, the Persian Gulf and the adjacent land areas. By 2000, the American Navy was the predominant Navy in the Indian Ocean.

IN PERSPECTIVE

By 1995, there were a host of navies trying to exert influence in the Indian Ocean region. Apart from the Americans there were the French, who had the next most significant presence, the British (who though, a considerably reduced lot, retained relevance), the Chinese and the Japanese, who too had begun to show some interest, primarily to protect their own maritime interests.

Most of these forces displayed a long-term perspective about their operations in the region with a consistent and compelling rationale for maintaining presence.

AMERICAN NAVAL PRESENCE IN THE INDIAN OCEAN

The American presence in the Indian Ocean had Diego Garcia1 at the core of its larger strategy. There were three major considerations for the US presence in the Indian Ocean.

China’s growing economy needed to ensure uninterrupted energy supplies. To secure themselves against disruptions through the sea route, the Chinese were in the process of developing overland pipelines.

- First and foremost was the American desire to maintain a geo-strategic presence. It was a strategy based on long term considerations and not aimed at immediate objectives or securing access to oil (as was generally believed to be the case).2

- The second reason was to protect its vital interests in the region. Having made heavy investments over decades to safeguard their key interests in the Indian Ocean, the US positioned its forces in a manner to maintain and reinforce presence in the Persian Gulf. The US Fifth Fleet clearly intended to remain in the area with a huge intervention capability pre-positioned in Diego Garcia.

- The third reason was conceivably to do with the new threat of terrorism that the Americans faced in the 90s. By maintaining presence, they aimed to root out non-state terrorist outfits and strangulate their access to funds and arms.

FRENCH NAVAL PRESENCE IN THE INDIAN OCEAN

France saw its perceived commitment to its “˜Overseas Territories in the Indian Ocean “” Djibouti and the Island of La Reunion as overriding and catered for the defence of her island territories and erstwhile French colonies (which also had a considerable majority of French speaking people) in the Indian Ocean, by maintaining a substantial naval presence.

A very substantial proportion of Frances oil supplies came from the Persian Gulf. France considered her naval presence necessary to guard her oil routes. To appreciate how important the region was in her plans it may be useful to highlight that during the Iran”“Iraq war is 1980″“88, it formed a multinational force with USA and Britain that opposed the threat of closure of the Straits of Hormuz and the consequent disruption of oil supplies.

France also considered her presence in Djibouti as a stabilizing force in the conflict between Somalia and Ethiopia in the 1980s, and saw itself as a significant equalising agent.

CHINESE NAVAL PRESENCE IN THE INDIAN OCEAN

In the early 90s, there were strategic drivers for China’s presence in the Indian Ocean.

American desire to maintain a geo-strategic presence. It was a strategy based on long term considerations and not aimed at immediate objectives or securing access to oil.

- Need to Secure SLOCs. China was investing heavily to develop markets in Central Asia, Africa and South America and needed to secure the SLOCs to ensure the uninterrupted flow of raw materials from Africa and finished goods to its key export markets.

- Constant Energy Supply. Chinas growing economy needed to ensure uninterrupted energy supplies. To secure themselves against disruptions through the sea route, the Chinese were in the process of developing overland pipelines3.

JAPANESE NAVAL PRESENCE IN THE INDIAN OCEAN

After World War II, Japans security policy had been based on five basic tenets:-

- A commitment never to develop nuclear weapons.

- Civilian control of the military.

- An exclusively defence oriented military strategy.

- Dependence on the US”“Japan Security Treaty.

- Ensuring the security of oil supplies.

Japan got its oil supplies from the Persian Gulf through the Indian Ocean, the Straits of Malacca and the South China Sea. The country was totally dependent on imports for its oil and gas supplies. This overwhelming reliance on oil and gas imports required secure shipping lanes.

The nation had so far desisted from becoming a military power that could be perceived as a threat by neighbouring countries. It focused its military effort on self-defence and sea-lane protection and eschewed the development of a stand-alone military capability that might provoke regional arms races. Japanese law also banned participation in collective security measures. For these reasons, there had hitherto been no Japanese Naval presence in the Indian Ocean4. In light of the prevailing circumstances, however, it made sense for it to gradually build up a Naval presence in the Indian Ocean. In line with its new strategy, the Japanese Navy began to participate in the safeguarding of SLOCs and in undertaking patrols and peacekeeping duties.

CONCLUSION

The Indian Ocean remained a hub of major military activity in the 90s, primarily because of its strategic positioning on the map that resulted in a majority of the world sea traffic “” both in terms of energy trade and goods shipping, passing through its waters. It was an area inherently given to competition and rivalry. Navies of all hues vied with each other for “˜presence and “˜control. The “˜symbolism and status of controlling the waters of the Indian Ocean was also a significant factor. For the Indian Navy, presence on the Indian Ocean was a new reality that it needed to cater for in its future plans.