The Indian Ocean Region

The Indian Ocean is the third largest body of water on the globe, covering 20% of the earth’s surface. They are the waters of wealth as well as conflict, depending on who can exploit it for their ends. There’s a very good reason why that body of water is called the “Indian” Ocean. The Indian peninsula juts 1,980 kilometres into the Indian Ocean. 50% of the Indian Ocean basin lies within a 1,500 kilometre radius of India, a reality that has strategic implications. The area between the Gulf of Aden and Malacca Strait is seen as India’s sphere of influence. India is one of six countries in the world to have developed the technology to extract minerals from the deep sea bed.

Under the law of the sea, by adding up the sea waterways comprising territorial zone of 20 kilometres, contiguous zone of 40 kilometres, an exclusive economic zone (EEZ) of 320 kilometres, India has exclusive rights to explore mineral wealth in an area of 150,000 square kilometres in the Indian Ocean. The oceans are recognised as a repository of treasure and this add-on area gives India sovereign rights over all living and non-living resources with regard to activities for the economic exploitation and exploration of the sea. India has the status of pioneer investor in this region.

Under the law of the sea, by adding up the sea waterways comprising territorial zone of 20 kilometres, contiguous zone of 40 kilometres, an exclusive economic zone (EEZ) of 320 kilometres, India has exclusive rights to explore mineral wealth in an area of 150,000 square kilometres in the Indian Ocean. The oceans are recognised as a repository of treasure and this add-on area gives India sovereign rights over all living and non-living resources with regard to activities for the economic exploitation and exploration of the sea. India has the status of pioneer investor in this region.

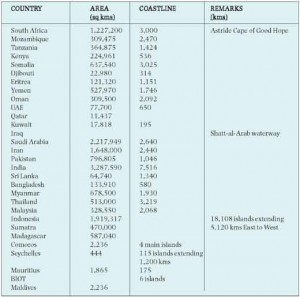

A look at the countries on the Indian Ocean littoral will give an adequate idea of the size and potential of India as compared to any other country in the region.

Geo-strategic Imperatives

The Indian Ocean provides major sea routes connecting the Middle East, Africa and East Asia with Europe and the Americas. It carries a particularly heavy traffic of petroleum and petroleum products from the oilfields of the Persian Gulf and Indonesia. Large reserves of hydrocarbons are being tapped in the offshore areas of Saudi Arabia, Iran, India and Western Australia. An estimated 40% of the world’s offshore oil production comes from the Indian Ocean. Beach sands, rich in heavy minerals, and offshore deposits are actively exploited by bordering countries, particularly India, South Africa, Indonesia, Sri Lanka and Thailand.

Today, nearly 20 million shipping containers are moving around the globe — carried by fewer than 4,000 hulls. The explosion of transoceanic trade has made commerce more vulnerable, not only in the obvious sense that economies have grown more interdependent, but also because, even as the volume of shipped goods increased, the number of significant cargo carriers has reduced because of the increasing size of commercial vessels, from supertankers to container ships. Far fewer transports ply the seas today than a century ago; the sinking, seizure or blockading of a small portion of the international merchant fleet could bring high-end economies to a standstill.10

Today, nearly 20 million shipping containers are moving around the globe — carried by fewer than 4,000 hulls. The explosion of transoceanic trade has made commerce more vulnerable, not only in the obvious sense that economies have grown more interdependent, but also because, even as the volume of shipped goods increased, the number of significant cargo carriers has reduced because of the increasing size of commercial vessels, from supertankers to container ships. Far fewer transports ply the seas today than a century ago; the sinking, seizure or blockading of a small portion of the international merchant fleet could bring high-end economies to a standstill.10

The Straits of Malacca, the world’s second busiest sea lane, assume relevance here. 80% of Japan’s oil supplies and 60% of China’s oil supplies are shipped through the Straits of Malacca. US$ 70 billion worth of oil passes through the straits each year. Almost half the world’s containerised traffic passes through this choke point. Most of the ships approach the straits through the 10 degree channel between the Andaman and Nicobar islands. India, thus, has the potential to dominate a strategic sea lane. India has established its first tri-service command, the A&N Command at Port Blair in the Andamans. It plans to develop Port Blair as a strategic international trade centre and build an oil terminal and transhipment port in Campbell Bay in the Nicobar islands.

India has exclusive rights to explore mineral wealth in an area of 150,000 square kilometres in the Indian Ocean.

India is a member of the Antarctic Treaty Parties Consultative Group and has already set up two permanently staffed scientific bases there. It has constructed a 10,000 foot runway in Antarctica to service future missions, having completed several successful landings there.

The Laccadive islands, likewise, offer the possibility of India projecting its power westwards. India is just 800 kilometres away from US military facilities in Oman. Trade with the Gulf States is an important facet of the Indian economy from ancient times.

The conflict-affected Indonesian province of Aceh sits at the tip of Sumatra i.e. the southern entrance of the Straits of Malacca. The Chola empire had an outpost in Aceh in early medieval times while the Portuguese, Dutch and British controlled it thereafter in succession. Aceh has large reserves of natural gas and minerals. The land mark peace accord between Acehnese rebels and Djakarta needs to be viewed in the context of this strategic sea lane.

India is uniquely placed between the two major drug and narcotics producing parts of the world, namely, the Golden Crescent, including Afghanistan, and the Golden Triangle, spanning the regions of northern Thailand, East Myanmar, and West Laos.

With increasing trade relations with the countries of the East, India has higher stakes in the region in the years to come. Trade volumes with the ASEAN countries have more than doubled in a decade. From a mere $1484 million in 1993, the Indian market has emerged as one of the largest importers of South East Asian goods with imports touching $ 10,942 million in 2004.11 The recently concluded Free Trade Agreements with countries like Thailand and Singapore are set to contribute to this trend. Expanding markets and larger import flows imply not only economic prosperity but also vulnerability at sea. The incidence of piracy, armed robbery and maritime terrorism are on the rise and has placed a premium on the complexity of sea-lane defence.

The Indian Ocean is a “vital sea” for India12 and the northern part of which is of immense economic and strategic importance. India’s burgeoning economy entails new markets for import and export. India’s foreign policy orientation towards its eastern neighbours has spurred interest and attention there. India’s burgeoning economy, now forecasted to become one of the three fastest growing economies in the world, entails expansion of existing export and import markets. Being a sea faring nation with island neighbours has added to the need for safe sea-lanes in the inter-lying waters. The world’s busiest choke point in the straits of Malacca located here adds complexity to a strategic factor.

Threats in the Indian Ocean region

From the Straits of Malacca to the Horn of Africa, piracy is a major threat. The direct damage terrorist-pirates could do is limited, but their crimes would probably impede regional trade, with economic consequences, from lost business and customs revenue to insurance hikes that damaged fragile economies and multinational corporations alike. The worse scenario would be terrorist-sponsored pirates who engaged in sheer destruction with weapons of mass destruction.

Bangladesh, Myanmar and Thailand are known to be sources and conduits for sea-based smuggling rackets and arms-trafficking. The Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) is also to use foreign shipping vessels for gun running. It is estimated that about 30% of the total illegal arms trade in the world reaches India.

Major environmental problem in the Indian Ocean is the spilling of oil. Oil pollution in the Arabian Sea is well-documented by oceanographers.

India is uniquely placed between the two major drug and narcotics producing parts of the world, namely, the Golden Crescent, including Afghanistan, and the Golden Triangle, spanning the regions of northern Thailand, East Myanmar, and West Laos. India is sandwiched between these two and is thus both a convenient and vulnerable conduit and destination for drug and human trafficking. The sea routes from Thailand to Bangladesh to India are especially thriving with this dangerous trade. Drug peddling, production and distribution are often seen as the easiest form of financing subversive activities. The presence of liberation organisations is both the cause and effect of smuggling trade. Symptomatic to this trade is the illegal migration and trafficking of humans. A phenomenal number of people are attempting to enter richer countries illegally. This is soon to overshadow drugs as the largest illegal business in the world.13

Another major environmental problem in the Indian Ocean is the spilling of oil. Oil pollution in the Arabian Sea is well-documented by oceanographers. The Japan oceanographic centre has reported that during 1975-80, on 495 out of 611 occasions, oil slicks were sighted in a sample quadrant close to Goa.14 This is highest frequency of oil slicks in the Indian Ocean. It is higher than even the transects surrounding Sri Lanka, which is close to the supertanker lanes.

The security environment in the northern Indian Ocean is being challenged from several directions. The region is plagued with piracy, drug smuggling, gun running and illegal migration.

Efforts have been made by states to address these problems and there has been an encouraging response from states but only as part of a bilateral agenda.

Efforts have been made by states to address these problems and there has been an encouraging response from states but only as part of a bilateral agenda.

The China Factor

China has not been unaware of these developments. It is in the processing of building a ‘string of pearls’ around India. It developed a naval facility, including submarine infrastructure, at Sittwe on Hanggyi Island; electronic posts at Manaung, Hanggyi Zedetkyi and on the Greater Coco island in Myanmar (Burma) in the Bay of Bengal. This island formed part of India until 1954 and lies just 50 kilometres from the Andamans. It is an ideal location to monitor Indian naval and missile launch facilities.

China hopes to establish a naval base in Marao (25 miles from Male) in the Maldives from where the Chinese navy proposes to deploy nuclear submarines fitted with sea launched Dong Feng. China is building a dual purpose naval facility in Gwador in Baluchistan, besides assisting in the construction of new ports at Ormara and Keti Bandar in Pakistan. And it hopes to build a naval base in Bandar Abbas in Iran overlooking the strategic Straits of Hormuz. US$ 200 billion worth of oil passes through the straits each year.

Analysis

India has expanded its security horizon beyond its territorial defence. India is essentially a maritime nation with a coastline of nearly 7,500 kilometres which falls halfway to the nation’s land frontier of 15,000 kilometres. With the continental shelf, the sea frontiers extend manifold. However, India has so far been able to explore only half of the area i.e. 75,000 kilometres bringing out 9.5 metric tonnes of natural wealth. Ninety per cent of India’s trade is ferried through sea, making it a lifeline of the nation’s economic prosperity. However, despite the lack of sea consciousness India is the sixth largest producer of fish and possesses the seventh largest merchant shipping fleet.

China is in the processing of building a “˜string of pearls around India. It developed a naval facility, including submarine infrastructure, at Sittwe on Hanggyi Island; electronic posts at Manaung, Hanggyi Zedetkyi and on the Greater Coco island in Myanmar (Burma) in the Bay of Bengal.

The world shipping tonnage puts India at the 17th position. The country has 12 major and 175 small ports. There are inadequacies in terms of infrastructural growth, port congestion, lack of networking and communication, poor power and water links and the mafias. Even though India has achieved a high degree of self-reliance in the field of marine science and technology, it has failed to exploit its sea opulence judiciously.

The Maritime Draft Policy aims to develop India’s maritime sector with new projects for developing shipping, ports and waterways. Of special significance is the Rs 10,00,000 Sagarmala project. However, a lot needs to be done in strengthening, infrastructure as it is causing a major loss to the exchequer as Indian port operations are being circumvented by Singapore, Dubai and Colombo.

A greater Indian Ocean strategic alliance could be to the 21st century what the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation was to the 20th : A military alliance that prevents a catastrophic war and fosters regional cooperation. A vision to grasp the command of the Indian Ocean will be decisive to the global future. Both, India and the US have conducted several exercises at sea in the recent past and carried out joint patrolling in the Indian Ocean upto the Malacca Straits to combat piracy and protect the sea lanes of communications.

“At the same time, India will play an increasingly international role. Its goals are analogous to those of Britain east of the Suez in the 19th century – a policy essentially shaped by the Viceroy’s office in New Delhi. It will seek to be the strongest country in the subcontinent, and will attempt to prevent the emergence of a major power in the Indian Ocean or South East Asia. What ever the day to day irritations between New Delhi and Washington, India’s geopolitical interests will impel it over the next decade to assume some of the security functions now exercised by the United States.”15

Conclusion

International politics arises out of the fact that the surface of the earth is divided very unequally from place to place, into political units that are independent and sovereign. Though all members of the UN are entitled to equality, they differ in location, area, population, political organisation, language, economic and cultural levels. They also differ in attitudes, aspirations, military strength, stages of development and political stature. Their relations with other states, whether close and friendly or adverse and hostile, vary both locally and at long range.

| Also read: |

Each state seeks, above all, to increase its economic well-being and ensure its security and survival. It is not an easy task in an environment where eternal and internal dangers underline the need for awareness and caution in state policy. History and geography mould the attitudes and policies of changes, even though these may be subject to sudden and unpredictable changes. Each state is a unique entity with characteristics of its own. It is helpful to try and discover its raison d’etre. Definition of national aspirations is a start point in any defining of national interests.

India is poised to achieve great power status. It needs to play its cards well otherwise the 21st century is Indias to lose.

The inter-locking mechanism of nation-states is now so delicate that events at one point can cause repercussions widely and remotely. Local events and situations can quickly acquire international interest and importance. (The “butterfly effect” explains that small variations of the initial condition of a dynamical system may produce large variations in the long term behavior of the system). Geographical analysis can offer more towards the understanding of international politics than just an appreciation of the facts of the location or situation.

Problems exist whenever states are enclosed within arbitrary boundaries, originally chosen by their imperial rulers and poorly supported by undeveloped economies. They thus face the dubious prospects of successfully charting their courses alone, in the troubled arena of international politics. The notion of ‘independence’ intrudes unhelpfully in an interdependent world.

| Editor’s Pick |

A major challenge to the international system is posed by the competition among different nations for land, resources and power. This challenge is as old as history itself. Survival of over-populated and under-nourished countries of the subcontinent, with any kind of self respect or honour, in the emerging world order will be so much more difficult unless they take note of the unifying factors and cooperate.

India is poised to achieve great power status. It needs to play its cards well otherwise the 21st century is India’s to lose.

Notes

- Amartya Sen; “The Argumentative Indian: Writings on Indian History, Culture and Identity”; (Allen Lane, London; 205) p.152

- Andrew Gyorgi, The Geopolitics of War: Total War and Geostrategy” ; The Journal of Politics, Vol. 5, No. 4 (Nov 1943) pp. 347-362.

- The Economist – 3 January 1998

- Indian Ministry of External Affairs, Annual Report: 2003-04, p.1.

- Quotes from C. Raja Mohan, Crossing the Rubicon (New York : Palgrave Macmillan, 2004), p.262: and C. Raja Mohan, “India’s Diplomatic Spring”: Indian Express, 22 March 2005.

- C. Raja Mohan; Foreign Affairs, Jul-Aug 2006

- As measured in GDP in Dominic Wilson and Roopa Purushothaman, “Dreaming with the BRICs: The Path to 2050”. Goldman Sachs Global Economics Paper, No. 99, October 2003, p.4.

- Manmohan Singh, Prime Minister of India, in his inaugural address at the Hindustan Times Leadership Initiative; Ed: Namita Bhandare: “India and the World: A Blueprint for Partnership and Growth”; Roli Books; New Delhi, 2005; p.23

- UN Monthly Bulletin of Statistics: Coca Cola – Forbes Estimates; http://unstats.un.org/unsd/mbs/

- Ralph Peters; Waters of Wealth and War: The Crucial Indian Ocean; http://www.armedforcesjournal.com/2006/03/1813970

- Donald L. Berlin, ‘India in the Indian Ocean’, Naval War College Review, Spring 2006, Vol.59, No.2, p.59

- Bradford, John; “The Growing Prospects for Maritime Security Cooperation in Southeast Asia”, Naval War College Review, Vol 58, No. 3, Summer 2005; p.72

- Dr. Sengupta & SZ Qasim ed., “The Indian Ocean”, Volume 1, Oxford and IBH, 2001

- Nandkumar Kamat, “Goa: Marine Pollution Management Needed”, The Navhind Times, March 28, 2005, http:/ www.navhindtimes.com stories.php?part=news&Story_ID=03283

- Henry Kissinger; Newsweek: September 19, 1988

- Source: World Development Indicators database (http: www.worldbank.org). Statistics for 2004; figures marked with + indicate data for previous years.

- The Military Balance 2005-2006

- ibid.