While having agreed in principle the idea that expansion of connectivity takes place between countries, India has not yet confirmed or regret its attendance at the China’s Belt and Road(OBOR)Forum to be held in Beijing on May 14-15. India’s non-participation involves serious reservation about OBOR as it violates India’s sovereignty[1]. Indian strategic analyst who view OBOR in negative terms site China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) as violation of India’s national sovereignty[2].

The China-Pakistan Economic Cooperation (CPEC) as the flag-ship project of the OBOR passes through Pakistan Occupied Kashmir (POK) claimed as an integral part of Indian territory and under forceful occupation. Following the increase in terrorist violence and Pakistan’s attempt to highlight the Kashmir issue both houses of parliament passed a resolution on 22 February (1994) declaring the state of Jammu and Kashmir integral part of India and that Pakistan must vacate parts of state under its occupation[3].

The resolution firmly declares that-(a) The State of Jammu & Kashmir has been, is and shall be an integral part of India and any attempts to separate it from the rest of the country will be resisted by all necessary means;(b) India has the will and capacity to firmly counter all designs against its unity, sovereignty and territorial integrity; and demands that -(c) Pakistan must vacate the areas of the Indian State of Jammu and Kashmir, which they have occupied through aggression; and resolves that -(d) all attempts to interfere in the internal affairs of India will be met resolutely.”The Resolution was unanimously adopted and unanimously passed. Hence, its operational meaning includes a possible military use of force for upholding India’s territorial integrity and sovereignty.

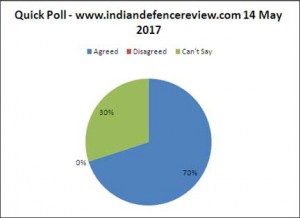

Online Quick Poll Research Question – China has been grossly insensitive to India’s sovereignty claims in POK by continuing to progress its CEPC project. In response should India threaten to cut off the Western Highway passing through Indian territory of Aksai Chin?[4].

Finalised in April 2015 on the basis of 51 agreements, the CPEC consists of a series of highway, railway and energy projects, emanating from the newly developed port of Gwadar on the Arabian Sea, all of which taken together will be valued at $46 billion. These projects will generate 700,000 jobs in Pakistan and, when completed, add 2-2.5% to the country’s GDP.While intra-regional trade has benefits, providing security to trade and investments made therefore has strategic consequences. For example, along with distribution of China’s domestic surplus capacity in infrastructure building overseas, China has increased the strength of its marine corps from 20,000 to 1,00,000 (Six Brigades – Provisional) for overseas contingencies and sought a reduction in its land forces by 3,00,000[5]. The additional trained marines are likely to be stationed at offshore supply ports Djibouti (Red Sea – Horn of Africa) and Gwadar (Pakistan) overlooking the Strait of Hormuz providing strategic impetus in regulating Middle East peace and stability.

Concerns for security are not exclusive to China alone, other major powers United States, Japan and France too conduct military operations from bases in Djibouti[6], while China, India and Japan have been carrying out long-distance naval deployment along north Indian Ocean since 2008-09[7].This militarised component of OBOR has led some in Indian strategic community to believe that the role of extra-regional power struggle (geo-political & geo-strategic) in Indian Ocean to have profound correlation to India’s broad national security concerns in the region. Hence, India has out of no choice strengthened its strategic partnership with both Japan and US in last decade as a direct consequence of increase in China’s defence expenditure particularly its naval arm (15%).Both Japan and US have begun to invest in Indian Navy’s three-dimensional quest for sea-control in Indian Ocean. A special attention is being paid to Indian Navy’s Anti-Submarine Warfare (ASW) capability which allows India to exert control over Indian Ocean from Gulf to Malacca.

Having empathised with India’s genuine security concerns, China has attempted on its part to factor in India’s geo-strategic concerns and put forth the following 4-point solution to “manage differences” apart from suggesting to rename CPEC and disconnect OBOR with sovereignty issues. At a closed-door meeting held at United Services Institute (USI), New Delhi on 05 May Chinese Ambassador to India Luo Zhaohui proposed the following[8];

• A New Treaty on Cooperation

• Restarting Talks on a Free Trade Agreement

• An Early Resolution to the Border Issue

• Aligning OBOR with India’s Act East Policy

While both India and China agree that trade (intra-regional) will determine Asia’s economic outlook in the 21st century, India’s non-participation at the multi-national OBOR forum where heads of state from at least 28 countries will participate needs a careful rethink[9]. India’s strategic concerns must be factored in without compromising the potential economic gains to be made by participating at the OBOR Forum where all South Asian Association of Regional Cooperation (SAARC) members have signed the 60-nation infrastructure initiative first proposed in 2013, but India[10].The strategic implication of OBOR is a matter of India’s national security, however it has been articulated and understood as China’s unilateral approach towards its own national security while posing regional challenges and opportunity[11]. India herself is engaged in securing its own perception of strategic communication lines with Middle East and South East and in-vogue prior to the declaration of OBOR[12].

While Indian approach remains unaffected by OBOR its strategic consequences remains a genuine challenge to India. Furthermore, India stood to gain from Chinese investment in port facilities in Sri Lanka[13], however investments of similar nature in Pakistan where China plans to invest in Gwadar (Arabian Sea) would give China a permanent naval presence in the western Indian Ocean and a commanding position at the mouth of the Gulf. China strategic predicament with respect to its “Battle for Access” is clear and present in its strategic understanding of the importance of Pakistan in Indian Ocean as witnessed by the strengthening strategic bond between the Pakistan Navy and People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN).

Admiral Wu Shengli, former PLAN commander, was conferred with Pakistan’s highest military award, Nishan-e-Imtiaz (Military), on 11 May in recognition of his distinguished services and significant contributions in strengthening the bilateral relations between Pakistan and China in general and Navies of both the friendly nations in particular[14].This dramatic expansion of the Chinese naval forces into what India sees as its strategic backyard is a matter of long-term concern for India. It has been perhaps the driver of Japan-US-India-Australia maritime partnership in the Indo-Pacific region[15].

While China’s leading scholars portray OBOR as a benign foreign policy to distribute China’s over-built domestic capacity in infrastructure development and financial assistance to strategic regions important to China[16], the strategic consequence of such a policy have direct bearings with China’s national security consciousness and of the region. The following is the brief summary of the possible strategic reasoning behind China’s OBOR.

• China’s economy requires it to exert influence abroad to maintain the momentum of its economic growth, which has for natural reasons slowed in recent years. Deteriorated conditions in Middle East or Eastern Europe have direct effects on China’s trade and economic prosperity. It is expected that some of the security problems such as terrorism can be resolved by fostering long-term economic development and prosperity by reducing poverty[17].

• The issue of interconnectivity was first emphasised by China’s border provinces such as Yunan, Xingjian, and Fujian. It was consolidated into a major national project having sensed its grand strategic potential that attempts to neutralise China’s traditional disadvantage referred to as “Battle of Access” via land and sea. OBOR’s successful implementation over a period of time will provide China’s foreign policy makers to influence regional crisis erupting faraway in Middle East, Central Asia, and Eastern Europe by increasing its stake and regional reputation along with credible influence.

• By way of investing in infrastructure development and financing other key social sectors, China intends create a favourable external environment in order to conduct meaningful trade and foreign relations. Efficiency produced by new transportation grids will increase the profitably of economic transaction and reduce cost[18].

• Implementation of OBOR is further guided by China’s need for a peaceful rise and Chinese dream that seeks to avoid confrontation and quell the China threat theory by linking its own security with others. This provides China with enhanced flexibility in controlling and shaping external events that have direct bearings for China’s own national security and development. As part of China’s Security Vision for the Asia-Pacific Region China envisages the Concept of Common, Comprehensive, Cooperative and Sustainable Security along with Improving the Regional Security Framework[19].

• China’s OBOR policy thus reassures China of its own ability and independence in realising its set national objectives articulated within the recent promulgations of Chinese dream by relating its economic gains to geo-political and geo-strategic gains. Both United States and Japan are now seriously contemplating joining Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) with China at its core[20].

• China therefore, through OBOR initiative attempts to comprehend and resolve its national security issues pertaining to its economy and security by way of comprehensive calculation in long-term. For example, unlike the previous efforts for transnational commercial linkages, China’s OBOR is as much people and cultural centric as commercial.

From an Indian perspective, while it has not objected to OBOR (barring CPEC) in principle it must remain conscious of the potential long-term geo-political and geo-strategic gains made by China. India must decipher the inherent strategic consequences of this initiative in a long-term perspective with respect to its own national security requirements. For India, it is essential to recognise that OBOR or any other such multi-national initiative is unlikely to produce efficient results without India’s unequivocal partnership[21].

From a geo-strategic perspective, India retains the advantage at sea through which part of the OBOR -21st Century maritime Silk Route- passes along with the domestic economic transformation that’s underway. The other half of OBOR Silk Road Economic Belt passes through regions that are Islamic and India must take advantage of its traditional linkages to deal with the strategic consequences arising out OBOR. India’s relation with China despite long pending border dispute has shown resilience where both countries have attempted to display strategic alignment by creating multi-lateral institutions that are oriented towards developing economies (RIC, BRICS, NDB, AIIB), a project that failed to take-off with the 1955 Bandung Conference given poor material capability of India and China.

A framework for India’s strategic interpretation of OBOR includes the following key points;

• OBOR is China’s unilateral comprehension of its strategic reality and a comprehensive strategic framework to address its strategic requirements in both economic and security spheres.

• It is not India centric, however it may or may not have strategic consequences for India in long term, if not in near future. India’s predominant position in India Ocean is unlike China’s strategic quest to guard lines of communication from a global perspective.

• Despite pending resolution of border between the two, China and India have multiple reasons for strategic alignment as both countries have noticed in recent past.

• India’s potential economic power in near-long term, can be used to manoeuvre around the strategic consequences arising out of OBOR along with India’s traditional role in Indo-Pacific region.

Conclusion:

While India’s decision to neither consent nor regret its participation at the OBOR Forum at Beijing is genuine and a possible rupture in the bilateral relations, both India and China must see the opportunity in the crisis. China and India can perhaps use this crisis to negotiate the new normal in the bilateral relations, where India can seek China’s unequivocal acceptance of India’s “one-Jammu and Kashmir” policy in line with China’s “One China” policy and a China’s admission of Pakistan occupied Kashmir (PoK) being a disputed territory between India and China along with a strategic commitment that all infrastructure construction in PoK be undertaken by Pakistan and not China[22], which will neutralise India’s objection to the highway passing via PoK under the OBOR’s flag ship project CPEC. China on the other hand can seek India’s strategic acceptance of the importance of the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road over which India has a dominant position to shape events. A meaningful negotiation of a new security cooperation treaty as put forth by China’s Ambassador to India last week may perhaps be an opportunity that this crisis has imbedded within it.

From a theoretical perspective while OBOR may appear a checkmate (#) where India will lose its immediate neighbours to China as their largest trading partners and the geo-political and geo-strategic influence that follows it, in practice uncertainty over the land domain part of OBOR (Silk Road Economic Belt) that passes through the Islamic world and the sea domain (21st Century Maritime Silk Road) part of OBOR dominated by west is a complex affair and investments made thereof double-edged sword. It is only in-action that will make OBOR a strategic checkmate (#), despite the fact that India has multiple options to deal with the strategic consequences.

[1]Arun Jaitley (Union Finance Minister, India) cited in Suresh Seshadri (2017), “We Have Doubts on China’s OBOR Project: Minister Cites Issues of ‘sovereignty’”The Hindu, 06 May, 2017. Available at http://www.thehindu.com/news/national/we-have-doubts-on-chinas-obor-project-jaitley/article18401482.ece [Accessed on 09 May, 2017].

[2]C.Raja Mohan (2017), “Network is the Key: India Must Ramp Up Its Internal Connectivity to Counter China’s Belt and Road Initiative”Indian Express, 09 May, 2017. Available at http://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/network-is-the-key-4646728/ [Accessed on 09 May, 2017].

[3]Text of theResolution Available atwww.satp.org [Accessed on 05 May, 2017]

[4]Through an online public Quick Pollconducted by the Indian DefenceReview based in New Delhi as on 14 May, 2017for the above-mentioned research question to be answered in “Yes”, “No”, and “Can’t Say” categories. “Quick Poll” Indian Defence Review, Available at https://www.indiandefencereview.com [Accessed on 14 May, 2017].

[5]Minnie Chan (2017), “As Overseas Ambitions Expand, China Plans 400 Percent Increase to Marine Corps Numbers, Sources say” South China Morning Post, 13 March, 2017. Available at http://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy-defence/article/2078245/overseas-ambitions-expand-china-plans-400pc-increase [Accessed on 09 May, 2017].

[6]SCMP Editorial (2015), “Chinese military base in Djibouti necessary to protect key trade routes linking Asia, Africa, the Middle East and Europe” South China Morning Post (Insight and Opinion), 01 December, 2015 (Updated on 01 May, 2017). Available athttp://www.scmp.com/comment/insight-opinion/article/1885396/chinese-military-base-djibouti-necessary-protect-key-trade [Accessed on 09 May, 2017]. Tomi Oladipo (2015), “Why Are There So Many Military Bases in Djibouti” British Broadcasting Corporation, 16 June, 2015. Available at http://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-33115502 [Accessed on 09 May, 2017]

[7]S. Rajasimman (2009), “China’s Maritime Thrust in Africa” Indian Defence Review, Vol:24; No:2 Apr-Jun (On Line Publication date 13 September, 2012). Available at https://www.indiandefencereview.com/spotlights/chinas-maritime-thrust-in-africa/

[8]Note: The fact that details of an indoor meeting between the Chinese Ambassador and Retired Armed Forces Officers on 06 May has found its place in media indicates a deliberate leak to retain flexibility in decision making on India’s part prior to the start of OBOR Forum in Beijing on May 14-15.Suhasini Haider (2017), “China Offers to Rename OBOR to Allay India’s Fear” The Hindu, 08 May, 2017. Available at http://www.thehindu.com/news/national/china-offers-to-rename-obor-to-allay-indias-fears/article18410413.ece [Accessed on 09 May, 2017].

[9]“China Maps Out ‘One Road, One Belt’ With Action Plan” Global Times, 04 May, 2015. Available at Globaltimes.cn [Accessed on 10 May, 2017]

[10]Rajiv Ranjan (2017), “How Can China Convince India to Sign Up For “One Belt, One Road: New Delhi Has Its Concerns With OBOR, Are They Entirely Insurmountable?”The Diplomat, 05 May, 2017. Available at http://www.oborforum.org/ [Accessed on 09 May, 2017].

[11]According toFormer National Security Advisor Shivshankaran Menon – (2017)

[12]Indian Ambassador (Retd) Talmiz Ahmed (UAE, Oman, and Saudi Arabia) – (2017)

[13] As part of a series of interview given by Mr. Menon to various media channels on his latest book “Choices: Inside the Making of India’s Foreign Policy”

[14]The award was conferred by Abdul Quadir Baloch (Federal Minister for States and Frontier Regions), held at Pakistan Navy Dockyard. Admiral Muhammad Zakaullah (Pakistan Chief of the Naval Staff), Ambassador of China, Air Officer Commanding South and other senior officers of armed forces attended the impressive ceremony. Zhang Tao (2017), Pakistan Observer, 11 May, 2017. Available at http://english.chinamil.com.cn/view/2017-05/11/content_7597319.htm [Accessed on 14 May, 2017].

[15]Author (2017) – Forthcoming

[16]Discussion with Professor Wang Qiu Bin (Deputy Dean), School of International Relations and Public Affairs, Jilin University (Changchun), People’s Republic of China. 20 November, 2016.

[17]Yukio Hatoyama (2017), “AIIB: A Dream Provider” Beijing Review, 02 February, 2017.

[18]In 2016, China’s outbound direct investment in non-financial sectors reached $161.7 billion, and its outbound investment surpassed the foreign investment it attracted, making China a net exporter of capital. Ding Yuan (2017), “How Can China’s Overseas Investment Be More Successful?” Beijing Review, 26 January, 2017.

[19]“China’s Policies on Asia-Pacific Security Cooperation (1 [中国的亚太安全合作政策)” January 2017. Available in (Document) Beijing Review, No.04 January 26, 2017.

[20]As a budding multilateral financial institution, it has delivered a satisfying report: $1.73 billion worth of loans were issued to nine energy and infrastructure construction projects in seven countries, and among the G-7, only the United States and Japan have not submitted an application to join the institution.

Yukio Hatoyama (2017), “AIIB: A Dream Provider” Beijing Review, 02 February, 2017.

[21]“China Must Take Competition from India Seriously”Global Times, 10 January, 2017.

[22]Lt Gen JS Bajwa (Retd) Editor, Indian Defence Review – 12 May, 2017.

OBOR serves NO purpose for India. OBOR will create No new trade route for trade with India. India has nothing to gain but more to lose from it.