As a rising power that detests competition, China might continue to test India’s resolve and patience through pinpricks on the border issue while progressively enhancing the level of engagement on the economic front and cooperating over global environmental concerns. In all likelihood, China will continue to promote activities that militate against the security interests of India. It is in light of these developments that the capabilities of the People’s Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF) must be assessed. Is the PLAAF finally spreading its wings? Does its sustained modernisation drive over the last two decades pose new challenges for India?

Two recent statements by Indian political leaders reflect the current state of Sino-Indian relations. On November 30, 2011, the Indian Defence Minister AK Antony admitted that the People’s Republic of China (PRC) had created some, “situations along the Line of Actual Control (LAC) that could have been avoided but which were due to different perceptions of the border.” Although the borders remain un-demarcated, disputes have been managed through established mechanisms such as hotlines, flag meetings and meetings of commanders of both sides. Consequently, the Sino-Indian border has been quiet and tranquil. On December 04, 2011, Omar Abdullah, the Chief Minister of Jammu & Kashmir expressed concern over Chinese involvement in the Kashmir region and urged India, “to show more spine” while dealing with China.

In the recent past, China has taken strong objection to oil exploration by India in collaboration with Vietnam in the South China Sea. The Indian Prime Minister has stated that this is purely a commercial activity in the ambit of international law and has clearly signalled India’s resolve to continue with the exercise.

It should be evident from the above that in the foreseeable future, Sino-Indian relations might be troubled and problematic. As a rising power that detests competition, China might continue to test India’s resolve and patience through pinpricks on the border issue while progressively enhancing the level of engagement on the economic front and cooperating over global environmental concerns. In all likelihood, China will continue to support Pakistan, a policy that would militate against the security interests of India. It is in light of these developments that the capabilities of the People’s Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF) must be assessed. Is the PLAAF finally spreading its wings? Does its sustained modernisation drive over the last two decades pose new challenges for India?

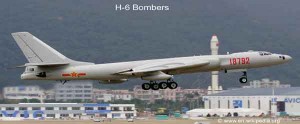

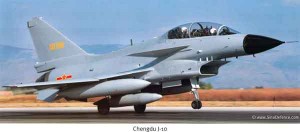

In September 2010, the PLAAF deployed six H-6 bombers escorted by two J-10 fighters to Kazakhstan during the Shanghai Cooperation Organisations (SCO) Peace Mission 2010 exercise. In October 2010, the PLAAF sent four J-11 (Chinese version of the Su-27) supported by one Il-76 aircraft to Konya in Turkey to participate in the Anatolian Eagle 2010, a bilateral exercise. The contingent staged through Iran which provided the required transit facilities. This was the first time that the PLAAF had deployed its air assets at such a distance from the Chinese mainland and engaged in an exercise with a NATO member nation. There were fears in the US about the potential of Transfer of Technology, particularly since Turkey operates F-16 fighters acquired from the US. Turkey, however, assured the US that no such transfer would take place.

In September 2010, the PLAAF deployed six H-6 bombers escorted by two J-10 fighters to Kazakhstan during the Shanghai Cooperation Organisations (SCO) Peace Mission 2010 exercise. In October 2010, the PLAAF sent four J-11 (Chinese version of the Su-27) supported by one Il-76 aircraft to Konya in Turkey to participate in the Anatolian Eagle 2010, a bilateral exercise. The contingent staged through Iran which provided the required transit facilities. This was the first time that the PLAAF had deployed its air assets at such a distance from the Chinese mainland and engaged in an exercise with a NATO member nation. There were fears in the US about the potential of Transfer of Technology, particularly since Turkey operates F-16 fighters acquired from the US. Turkey, however, assured the US that no such transfer would take place.

All three branches of the PLA have carried out numerous exercises in the last two decades. It was in the 1990s that the PLAAF was, for the first time, accorded the authority to “coordinate a joint exercise opposite the Taiwan Strait” signalling the intent of the PLA to play a dominant role. Most of the exercises conducted inside China involved joint operations, para-drop, strategic lift and operations from satellite airfields. The strategic lift exercise, Stride 2009 involved the movement by air and surface transport of a division plus strength of troops from the East to the far end of the country in the West. In the absence of detailed information, it is difficult to accurately assess the actual offensive potential of the PLAAF but emphasis on Rapid Reaction Units, education, joint and Special Forces operations, computer education, increasing reliance on space-based systems and synergy with cyber operations show that the China is serious about transforming its air force to enhance its reach and firepower.

Undoubtedly, the PLAAF has come a long way since the 1970s when it possessed some 5,000 aircraft, a mix of different types. However, only a few of those were really airworthy or posed any threat to China’s neighbours. When the PRC sent a Chinese Volunteer Army consisting of some six corps to fight in the Korean War, only a few pilots in the PLAAF were able to fly the Soviet MiG-15 against the American F-84, and later the F-86 Sabre fighters.

Aviation Industry in China

The threat of an American attack by nuclear weapons forced Mao Zedong to redouble China’s effort to develop nuclear deterrent capability with the necessary delivery systems. Although Russia helped China build a vast defence industry fashioned on the Soviet model, the PLAAF continued to suffer from ‘short legs’ or limited range and armament. During the 1950s and 1960s, operating in concert with Taiwanese forces, the US aircraft and warships regularly violated Chinese airspace and territorial waters. The PLAAF was too weak to retaliate. The focus of the PLAAF was air defence for which, despite their limited range, the Soviet-designed MiG-15, MiG-17 and later MiG-19 served the purpose. First generation Surface-to-Air Missiles, SAM II Guideline even shot down a few USAF U-2 spy planes. The PLAAF also manufactured the Il-28 light bomber and obtained the design of the Tu-16 long-range bomber but by then, relations between the two countries soured and almost all cooperation with the Soviet Union in the defence sector came to a halt.

Efforts were made to design and develop indigenous aircraft but due to China’s inability to manufacture suitable aero-engines, projects languished for years. However, it goes to the credit of Chinese engineers that despite the constraints, they succeeded in cloning the MiG-21 designated as the J-7/F-7 and also developed the J-8, a twin-engine variant of the MiG-19. In fact by 1984, China had already exported this highly agile and easy-to-maintain Chinese version of the MiG-21 to Iraq and other friendly countries.

Efforts were made to design and develop indigenous aircraft but due to China’s inability to manufacture suitable aero-engines, projects languished for years. However, it goes to the credit of Chinese engineers that despite the constraints, they succeeded in cloning the MiG-21 designated as the J-7/F-7 and also developed the J-8, a twin-engine variant of the MiG-19. In fact by 1984, China had already exported this highly agile and easy-to-maintain Chinese version of the MiG-21 to Iraq and other friendly countries.

The 1991 Gulf War came as a wake-up call to China. Her leadership suddenly realised that a nuclear deterrent alone was not enough when pitched against a modern air force that could blunt the capability to retaliate. What followed was the doctrine of ‘active defence’ that implicitly allowed even a pre-emptive strike and a renewed search for modern aircraft and weapons.

The PLAAF has some 1,687 combat capable aircraft up from 1,653 the previous year.Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russia was in serious economic difficulties. With her economy already booming, China immediately cashed in on the opportunity and signed a major deal for the purchase of 24 Su-27, roughly in the US F-15 class with the provision for the local manufacture of another 200 aircraft. China also purchased large numbers of Rolls Royce Spey-200 engines from the UK for the locally developed JH-7/FB-7 fighter bomber, accessed high technology from Israel and also purchased Russian aero-engines the RD-93 and Al-31 F to kick-start two other local fighter programmes. What emerged was the JF-17 Thunder co-produced with Pakistan and the J-10 based on the Lavi, an Israeli-designed fighter of the F-16 class. The Lavi programme had been abandoned by Israel supposedly under pressure from the US. Pakistan, incidentally, had allegedly supplied a crashed F-16 and a dud American Tomahawk Air Launched Cruise Missile to China to facilitate reverse engineering.

In less than two decades, the PLAAF has ‘leap-frogged’ two generations to reach a level significantly higher than where it was in the 1980s. Belying Western forecasts, China had deftly utilised her economic and diplomatic clout to transform the PLAAF into a modern air arm.

Not only did China focus on fighter aircraft but also developed, built, and wherever possible, blatantly copied the numerous designs of air-launched weapons and missiles, transport aircraft, helicopters and UAV/UCAV that were obtained from Russia and other countries. Flush with funds, China could get whatever she wanted from Russia. However, attempts to locally manufacture a cloned version of the Al-31F turbo-fan engine that powers the Su-30 have not as yet succeeded. Most China watchers believe that this feat could be achieved in the next few years. China would then have joined the elite club of nations with the capability to manufacture modern jet engines.

The venerable An-12 (Y-8) has been successfully modified into an AEW&C version with more powerful engines, new propellers and modern avionics. The WZ-10 is a locally produced armed/attack helicopter. Some 100 H-6, the Chinese version of the 1950s vintage Tu-16 bomber, modified, with more powerful Russian D-30KP engines, are still operational. This old bomber is now employed for roles such as flight refuelling, electronic surveillance and to deliver anti-ship cruise missiles while remaining out of harm’s way.

The Chinese have also test flown the J-20, their fifth-generation stealth fighter and are confident of inducting it into service by the end of the decade.

The PLAAF Challenge

According to the latest reports (IISS Military Balance 2011), the PLAAF has some 1,687 combat capable aircraft up from 1,653 the previous year. The Chinese aviation industry now has the capacity to manufacture 40-50 modern fighters every year. Such is the pace of progress that reliance on Russian technological support has now reduced to a great extant.

The PLAAF, however, has almost no combat experience nor has it participated in exercises with air forces other than the one with a few aircraft in Turkey last year. Yet if the type and variety of weapons, especially cruise missiles, UAV and UCAV and the focus on space-based systems such as the GPS/GLONASS, reconnaissance satellites are any indication, the PLAAF is by no means lagging behind other air forces in grasping the essentials of modern air power employment. A majority of the 1,687 combat aircraft, however, are of II/III generation. Barring some 144 J-10, a few Super-10, 243 Su-27/30 and 72 JH-7A, the rest comprise J-7 and J-8 of the older generation.

In addition, the PLA Navy’s aviation wing has some 311 combat capable aircraft with 24 Su-30 Flanker and 84 JH-7 fighter bombers with the remaining being J-7 and J-8 variants. Some 15 J-15, a locally manufactured version of the carrier-borne Su-33 are to join the PLA Navy’s new aircraft carrier, the Varyag.

In spite of the PLAAF and PLAN possessing a fairly large number of third generation or even slightly more advanced fighters, it is not clear if these would be used in their traditional roles. Given the strong influence of Sun Tzu’s philosophy of “winning wars without actually fighting”, the hangover of the People’s War dogma, PLA Army’s domination and relatively limited combat experience of the PLAAF, there is a possibility that the Chinese leadership might place a higher-than-normal reliance on the country’s missile force especially on the conventional short range ballistic missiles of the M-9 and M-11 variety. These weapons, available in large numbers, could well be used in the opening phases of a border conflict to convey Chinese political resolve and to keep attrition low. The terrain, large distances to airfields in Sichuan and Yunnan provinces (1,600km – 1,800km from Arunachal Pradesh to Chengdu and Kunming) and the limitations imposed by high altitude on fighter operations from Tibetan airfields could also force the Chinese to bank on conventional missiles. It is also debatable if on their way to targets in India, the Chinese aircraft would be allowed to fly over Myanmar and Bangladesh. As the crow flies, Mandalay is 805km from Kolkata, 821km from Tawang and 1,913km from Chennai. The Great Coco Island, that has only a 1,300-metre long runway, is just 284km from Port Blair.

In spite of the PLAAF and PLAN possessing a fairly large number of third generation or even slightly more advanced fighters, it is not clear if these would be used in their traditional roles. Given the strong influence of Sun Tzu’s philosophy of “winning wars without actually fighting”, the hangover of the People’s War dogma, PLA Army’s domination and relatively limited combat experience of the PLAAF, there is a possibility that the Chinese leadership might place a higher-than-normal reliance on the country’s missile force especially on the conventional short range ballistic missiles of the M-9 and M-11 variety. These weapons, available in large numbers, could well be used in the opening phases of a border conflict to convey Chinese political resolve and to keep attrition low. The terrain, large distances to airfields in Sichuan and Yunnan provinces (1,600km – 1,800km from Arunachal Pradesh to Chengdu and Kunming) and the limitations imposed by high altitude on fighter operations from Tibetan airfields could also force the Chinese to bank on conventional missiles. It is also debatable if on their way to targets in India, the Chinese aircraft would be allowed to fly over Myanmar and Bangladesh. As the crow flies, Mandalay is 805km from Kolkata, 821km from Tawang and 1,913km from Chennai. The Great Coco Island, that has only a 1,300-metre long runway, is just 284km from Port Blair.

Capabilities of the Indian Air Force (IAF)

Does it imply that the IAF cannot defend the Indian skies against this seemingly very formidable opponent? The answer is a definitive ‘NO’. As mentioned before, the actual offensive capability of the PLAAF is quite limited given the very large distances to their launch bases in mainland China and the severe payload limitations of fighter operations from the high altitude airfields in Tibet.

The PLAAF has a few Il-78 and ten H-6 converted into Tu-160 Flight Refuelling Aircraft (FRA). Their efficiency, state of training and employability however, remain somewhat uncertain. In the event of a face-off between the Chinese and Indian navies, the IAF may be called into action. Given the range, the IAF would have to undertake combat operations with the Su-30 fleet duly supported by FRAs.

The fleet of FRA with the PLAAF is neither large enough nor sufficiently trained to compensate for these limitations of operating from airfields at high altitude. Besides, the airfields in Tibet can be easily targeted by the IAF and hence would remain vulnerable. The IAF today has a fairly large number of combat aircraft and a small number of conventional missiles of the Prithvi class. The Su-30 MKI fleet in the East is being progressively enhanced and together with Mirage-2000 and MiG-29, would be able to counter any offensive by the elements of the PLAAF in Ladakh and Arunachal Pradesh. The situation would definitely improve once the Su-30 MKI fleet is built up to full strength and the 126 MMRCA and 40 Tejas Light Combat Aircraft are inducted into the IAF in the next decade. By 2020, hopefully the Indo-Russian Fifth Generation Fighter Aircraft would also be available to the IAF.

In the past, India has shown some reluctance to employ offensive air power in right measure. The combat elements of the IAF were simply not used for fear of escalation during the 1962 Sino-Indian War and India lost. Thirty-seven years later, in the 1999 Kargil conflict, the use of air power was delayed and then severely restricted to the Indian side of the Line of Control again for fear of escalation. It is therefore, essential that the country’s military and political leadership is prepared to demonstrate India’s resolve, without which all the expensive hardware would be utterly useless.

In the past, India has shown some reluctance to employ offensive air power in right measure. The combat elements of the IAF were simply not used for fear of escalation during the 1962 Sino-Indian War and India lost. Thirty-seven years later, in the 1999 Kargil conflict, the use of air power was delayed and then severely restricted to the Indian side of the Line of Control again for fear of escalation. It is therefore, essential that the country’s military and political leadership is prepared to demonstrate India’s resolve, without which all the expensive hardware would be utterly useless.

IAF resources would undoubtedly be stretched in the event of the Pakistan Air Force (PAF) also mounting an offensive in collusion with the PLAAF. But even in such a situation it would not be easy for them to prevail. Simultaneous and well-coordinated offensive operations by China and Pakistan are a remote possibility but one for which the country must be ever prepared. For a variety of reasons, at this point in time, neither China nor India is likely to seek to engage in an all-out, copy-book and set-piece conventional war. Firstly, India has consistently avoided using force even in the face of serious provocation by Pakistan. Secondly, for China, Taiwan and South China Sea disputes are of far greater strategic importance given the recently re-affirmed American interest in the region. This is not to suggest that Tibet and the so-called separatist forces in Xinxiang do not pose a serious challenge/threat to China’s national unity and territorial integrity. Thirdly, China is no longer the isolated country of the early Cold War era. Today, China is an important economic power with trading interests the world over and can hardly afford to sully her image as a responsible player. Fourthly, China’s dependence on maritime routes for exports and energy imports especially through the Strait of Malacca would also constrain her strategic options.

The possibility of a local border skirmish arising from a misunderstanding or misinterpretation of the situation viz the un-demarcated LAC cannot be ruled out. India would be well advised to sharply restrict the scope, both in time and space, of such a skirmish by resorting to carefully calibrated military/diplomatic responses without delay. In the meantime, the IAF must assiduously build up the capability for swift and effective response to any threat or proactive step by the PLAAF.

Conclusion

In August 2009, Admiral Sureesh Mehta, the then-Chief of Naval Staff had stated that India was not in a position to match China “force for force” and had advised a more technological solution to cope with the threat and not confront a rising China. In July 2011, Air Chief Marshal PV Naik, the then-Chief of the Air Staff had said that the PLAAF was three times the size of the IAF. While these statements are not very different from the suggestions by General Thimayya and Lieutenant General Thorat in 1960-1961, they may also be termed as ‘defeatist’.

Today, both India and China are very different. While China has no doubt shown a propensity to resort to aggressive language or even bullying, the actual use of force is another matter. Although slow in implementing steps in her defence preparedness, India is no push-over.

The IAF is well on its way to establish a network of light transportable radars, improved airfield infrastructure and the induction of new fighters, UAV/UCAV and a whole host of force multipliers such as the AWACS and FRA. Unfortunately, all of these are from foreign sources. China’s strategic defence industry has made spectacular progress leading her to be soon counted amongst the leading arms producing and exporting countries. Although the Indian economy too is on a growth trajectory, the power differential with China has been growing. Finally, although China and India are neighbours, fortunately their forces are neither in conflict nor in competition. Geography will continue to play a very critical and possibly, positive role in any future conflict, however, localised it might b