The 21st Century has been designated as the era of knowledge and knowledge workers. In the sphere of military operations, classical fire and manoeuvre has been gradually replaced by Information & Intelligence. A vibrant defence manufacturing sector can play a significant role in providing Technology Security to a Nation faced with the prospect of a two front war.

The FICV programme can become the forerunner for creation of a defence industrial base if rolled out and executed with untrammelled vision and direction.

Technology Security is a vital step in the strategic capability building of our nation which is cherishing ambitions for a permanent seat in the UN Security Council. It has the potential to generate millions of job for our young work force, save billions of dollars being spent on acquisitions and through life cycle capability management besides creating avenues for export by being cost competitive.

In addition, most defence technologies developed have significant applications in civil, internal security,disaster relief etc and would find use therein. In order to trail blaze this seemingly opaque work space, it is important that a defence technology strategy is put in place outlining the priorities for research, funding, skill development, opportunities and collaboration.

Defence Capability

The Make in India programmes needs to be viewed as a strategic step towards Defence Industrial capability building and long term technology security. If the Make in India initiative turns out to be an exercise of sourcing military capability from overseas by the private sector, the likelihood of military capability failure at crucial times will always be high, besides, nothing prevents the adversary from acquiring knowledge from overseas on means to neutralize/inhibit deployment of such capabilities.

For political/economic reasons, the overseas source may end up selling the same systems to a host of other countries. Sukhoi, Mi 17 are examples of these. Besides, the cost for life cycle system readiness would be exorbitant if dependence on foreign industrial base remains. A vibrant indigenous defence industrial base, where innovation and injection of new ideas is the norm, will contribute to achieving a battle winning edge by giving technological advantages over the opponents. The FICV programme can become the forerunner for creation of a defence industrial base if rolled out and executed with untrammelled vision and direction.

Pulling through of military technology into the civilian market will continue to be feasible in the future and hence Government funding in certain areas for setting up the country’s defence industrial base is desirable.

Defence Acquisition has to be seen as an exercise that not only looks at acquiring a combat capability but also an industrial capability to manufacture and resuscitate systems over a life cycle. It is not akin to procurement. It has to be more enabling and forgiving to encourage industry participation. It may be appropriate therefore to rename DPP as Defence Acquisition Guidelines instead of a procedure.

Technology Benefits

Defence Industrial bases of countries like US, UK, Germany, France, Russia, Israel etc in the past have been a source of innovation and technologies which had follow on application in civilian fields e.g. internet, cellular communications, surveillance systems, UAVs, prosthetics etc. These civil applications have provided the economics of scales for the technologies to be sustained and improved upon.

Pulling through of military technology into the civilian market will continue to be feasible in the future and hence Government funding in certain areas for setting up the country’s defence industrial base is desirable. But this investment has to be made with a difference, since earlier such investments in the public sector had not created significant industrial capabilities & knowledge cache. There are PSUs that have absorbed up to 6-7 foreign technology transfers, but are yet not capable of designing and fielding an elementary indigenous system. It is therefore essential to take stock of existing design/development capabilities within the country, identify capability gaps in technology after listing out capability surpluses and short falls and create a road map for future industrial capability development.

Acquisition should aim at bridging the technology gap & the lever of acquisition of a major systems like aircraft, missile system or naval systems should be used for acquiring know-how on critical sub-systems to bridge the technology gap.

FICV needs to be a home grown programme with technology transfer for only those systems that are not available indigenously.

Constituents of Defence Industrial Base

• Prime Contractor or Systems Integrator. An entity with industrial capability to deliver a complex system or product like an AFV, ship or aircraft. It requires high grade systems engineering skills, processes & tools to integrate a complex system and testing facilities to test & prove system functionalities.

• Partial System Manufacturer. These manufacture independent systems which while possessing independent purpose, are relevant when integrated in to a complex system e.g. air defence missile.

• Sub-system Manufacturer. They manufacture systems which give a capability to the complex system only when integrated with the platform e.g. a power pack will provide mobility to the platform, when integrated with rest of the running gear.

• Replaceable Units/Component Manufacturers. These entities generally MSMEs provide finished assemblies/aggregates/LRUs which form part of sub-systems/systems e.g. engine parts, PCBs, power supplies, sensors, harnesses, etc.

• Design Houses. These are knowledge based organisations (Design Authority) with unique systems engineering skills, a suite of modern organisational, modelling & simulation processes & tools and facilities to test & prove at system/sub-system level. They generally pick up sub-contracts from prime SIs for designing/testing of systems & have specialists who have deep insights into all levels of systems engineering & maintain knowledge of the system as a whole.

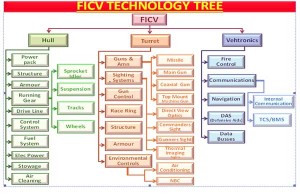

Given below is an approximate Technology Tree for the Future Infantry Combat Vehicle programme that is expected to be rolled out for the industry in the months ahead and could become the flagship programme of Make in India in the Defence Sector. The Technology Tree gives a useful insight into the supply chain requirements for this programme.

It is evident from that the FICV programme has the potential to put a large number of entities small & big in the overdrive, as hundreds of sub-systems & thousands of components will have to be manufactured in India. However, it would be ideal if a few design houses also spring up during the programme to give it an indigenous design & architecture. It is important to design & configure systems for our terrain & operating conditions ranging from deserts to mountains & high altitude areas in order to get the required Equipment Capability. Thus FICV needs to be a home grown programme with technology transfer for only those systems that are not available indigenously.

It is essential to build an elaborate technology & engineering ecosystem to mesh in indigenous technology and foreign technology that would come through JVs & technology transfers.

As on date capabilities to manufacture major sub systems of a combat vehicle (tracked or wheeled) are available with the public sector only, as a consequence of several technology transfers that have taken place. However, whether they will be able to build upon the knowledge cache available, to design new sub-systems for the FICV is yet to be tested. In the FICV programme, there would be a need for systems houses on power pack, running gear, main & secondary armaments , missile systems, the basic hull & turret, fire control systems, power traverse & stabilization system, surveillance & target acquisition systems, communication & battle field management systems, water propulsion systems, defensive aids suite etc.

Needless to mention these system houses will be supported by hundreds of unit / component level manufacturer from the SME ecosystem. If the entire programme is managed by a higher organisation, that can facilitate hand holding, collaboration, participation & knowledge sharing, control wasteful expenditure through unwarranted competition, the programme can be realised without costs & time overruns.

The entire programme must aim to develop affordable options to fill in the capability gap, through life capability management & manage technology & supplier risk to acceptable levels. No point developing a system, that has high levels of import content (Arjun, Pinaca&Brahmos) where initial acquisition costs & support costs hit through the roof or develop a system that has same capabilities as an upgraded ICV BMP.

It is essential to build an elaborate technology & engineering ecosystem to mesh in indigenous technology and foreign technology that would come through JVs & technology transfers. The Chinese technology development strategy of IDAR (introduce, digest, absorb & re-innovate) is a best practice which is worth an evaluation. One can only hope that with so many technology transfers that have already taken place, at least the mobility systems of the FICV would be an indigenous design. It could have been, had the practice of indigenous innovation been encouraged in our universities and R&D centres in the years gone by.

The FICV programme, if and when rolled out, could be a trail blazer for establishing a defence technology ecosystem for architecting, design, testing, evaluation & production of a major land system i.e. a tracked combat vehicle.

Israel, which has faced enormous challenges to its security, adopted the human capital intensive growth strategy where a lot of focus was placed on creating a knowledge & skill base in universities & Govt laboratories. This has created an exceptionally creative set of scientists & engineers for the high tech industry. Another practice which has helped Israel is the large no of conscripts who learn skills during their Army service & transfer it to civilian life upon release. Of course a liberal export policy did help. For us a combination approach of the two is most desirable to find cost effective solutions.

Another area where there is a know-how deficit is the classic `design for Ibilities`, a vital requirement of systems engineering. Knowledge on design for reliability, maintainability, usability, supportability, producibility, affordability (life cycle costs) and disposability is absent or at best sub optimal. The FICV programme must endeavour to create these technical capabilities in order to meet the measures of performance given in the qualitative requirements and bring out a combat vehicle that is engineered for combat in our operating conditions. Infrastructure for test and evaluation is only available with the Govt, as are the duty cycles for evaluating System Effectiveness. Ground rules to facilitate easy access to these by private players need to be framed for Type 1 and Type 2 testing.

The FICV programme, if and when rolled out, could be a trail blazer for establishing a defence technology ecosystem for architecting, design, testing, evaluation & production of a major land system i.e. a tracked combat vehicle. If a modular concept is encouraged, this programme could offer as offshoot, wheeled APCs of 4×4 & 6×6, 8×8 configuration for deployment in mountains, high altitude areas and island territories thus generating adequate economics of scale. Such operational innovations will come through if direct communication & close team work is maintained between the Army (users & sustainers), designers and producers of the FICV.

Really I appreciate for this column and I want to thanks like such a grate Sir.

I want number of Lt Gen NB Singh. Can you provide me.