In a move to streamline defence procurement and push the Make in India initiative, the Ministry of Defence (MoD) has constituted a nine-member committee under the chairmanship of Vivek Rae, former Director General (Acquisition) – DG (Acq). The committee’s Terms of Reference (ToR) require it to suggest a suitable organisational structure in light of international best practices. In this context, this Special Feature highlights the importance of studying the French procurement system.

Notwithstanding the establishment of structures and procedures, India’s defence acquisition has not progressed as desired.

India’s Defence Acquisition Framework: The Problems

India’s current acquisition framework consists, broadly, of a two-tiered structure, comprising the Defence Acquisition Council (DAC) and its subordinate bodies – the Defence Procurement Board, the Defence Research and Development Board and the Defence Production Board. This structure was created in 2001 in pursuance of the recommendations of the Group of Ministers (GoM), which was set up to review the “national security system in its entirety”. The acquisition procedures, which are captured in a document known as Defence Procurement Procedures (DPP), predate the current structure and were first announced in 1992. The DPP has been revised several times, the latest revision being in June 2016.

Notwithstanding the establishment of structures and procedures, India’s defence acquisition has not progressed as desired. Among the failures of India’s defence acquisition framework has been its inability to ensure time-bound procurement thus forfeiting available budgetary resources, as well as vulnerability to import-centric pressures, corruption and controversies. In the last 10 years alone, the MoD has forfeited a cumulative total of Rs. 51,515 crore of the allocated budget (see Table 1). It is partly because of these unutilised funds that modernisation of the armed forces has been delayed inordinately.

In its 2007 audit report, the Comptroller and Auditor General of India (CAG) had noted that the basic problem of India’s defence acquisition framework was its dispersed centres of responsibility and lack of professionalism in acquisition.1 Earlier, the GoM had suggested the creation of a “separate and dedicated structure to undertake the entire gamut of procurement functions … to facilitate a higher degree of professionalism and cost effectiveness in the process.”2 What has been created, however, is a decentralised system of procurement with little regard to professionalism, accountability and price discovery.3 There are too many independent actors responsible for various acquisition functions that include drafting of technical features, issuance of tender document, undertaking of trials and evaluation, providing quality assurance and making payment to vendors. These actors are neither trained for their assigned roles nor are they given adequate time to build institutional capacity.

Table 1. Utilisation of Capital Acquisition Budget (in Rs crore)

| Year | Budget Estimate |

Actual Expenditure |

Under/Over Spending |

Under/Over Spending (%) |

| 2006-07 | 31722 | 27818 | 3905 | 12.3 |

| 2007-08 | 34515 | 30398 | 4117 | 11.9 |

| 2008-09 | 40163 | 32423 | 7739 | 19.3 |

| 2009-10 | 43816 | 42025 | 1791 | 4.1 |

| 2010-11 | 47528 | 50396 | –2868 | –6.0 |

| 2011-12 | 56743 | 55578 | 1165 | 2.1 |

| 2012-13 | 66549 | 59151 | 7398 | 11.1 |

| 2013-14 | 73855 | 67161 | 6694 | 9.1 |

| 2014-15 | 75695 | 66227 | 9468 | 12.5 |

| 2015-16 | 77848 | 65742 | 12106 | 15.6 |

| Total | 548433 | 496918 | 51515 | 9.4 |

Notes: 1. Plus figures denote under-utilisation and minus figures over-utilisation.

2. Under/over-utilisation is based on the difference between budget estimate and actual expenditure in a given year except for 2015-16, where the difference is between budget estimate and revised estimate.

3. The capital acquisition budget is inclusive of “medical equipment”.

Source: Author’s database.

In contrast to India’s defence acquisition system, several countries such as the UK, France and Australia follow a more centralised system of procurement. France, in particular, has been highly successful in promoting a domestic-industry-driven procurement system.

Another major problem of India’s defence acquisition framework has been its lip service to indigenisation/self-reliance, which is now being manifested in the current government’s Make in India initiative. Although the DPPs of recent years have tried to buttress the self-reliance efforts through a host of measures,4 the acquisition system still harbours its step-motherly attitude towards indigenous industry, particularly private sector companies.5

The apathy towards domestic industry has been institutionalised by keeping the acquisition and production functions under two distinct power centres in the MoD. Though a mere brick wall separates the offices of the DG (Acq.) and Secretary (Defence Production) – the latter is responsible for indigenous arms production by both state and private entities – their meeting grounds remain far apart. While the former is keen on awarding contracts (so as to utilise the allocated resources) irrespective of the source of supply, the latter is interested in obtaining some contracts for the domestic industry, particularly the state-owned/controlled Defence Public Sector Undertakings (DPSUs) and the Ordnance Factory Board (OFB). Since the basic objectives of these two high offices are not necessarily driven by indigenous-centric procurement, the focus on indigenisation has become subservient to acquisition. It is primarily because of the inherent conflict of interests between these two high offices that domestic industry has not received the necessary attention it deserves,6 and India continues to figure among the top arms importers in the world.

The French Acquisition System

In contrast to India’s defence acquisition system, several countries such as the UK, France and Australia follow a more centralised system of procurement. France, in particular, has been highly successful in promoting a domestic-industry-driven procurement system. It is one of the few countries in the world to have developed an advanced defence manufacturing base that is capable of producing the full spectrum of military items, including nuclear weapons. Nearly 90 per cent of France’s defence requirement is produced indigenously,7 and the French authorities openly boast that their system has “inspired other countries to copy”.8 It is no surprise that the Kelkar Committee, appointed by the MoD to suggest measures to promote self-reliance, in its April 2005 report, Towards Strengthening Self Reliance in Defence Preparedness, suggested an examination of the feasibility of emulating the French system. The present Vivek Rae Committee might also follow suit.

DGA: The Linchpin

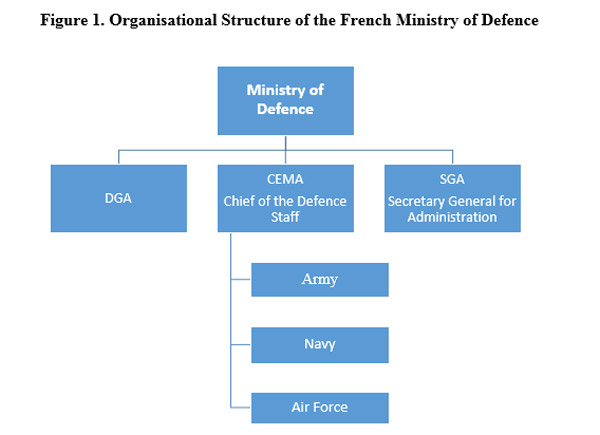

At the fulcrum of French defence procurement is the Direction Générale de l’Armement (DGA), one of the three pillars of the Ministry of Defence (Figure 1). The DGA is responsible for a vast array of defence acquisition functions relating to research, development, test evaluation, production and export of defence equipment. The DGA’s predecessor, the Ministerial Delegation for Armament (DMA), was set up on 4 April 1961 by President Charles de Gaulle by merging service-specific armament directorates dealing with land, naval and air equipment and powder manufactures into one entity. The DMA was renamed as DGA in 1977.

Prior to the DMA’s formation, the fragmentation of the industry and its non-synchronisation with the genuine requirements of the defence forces was the main hurdle in France becoming a major armaments producer. France had earlier attempted to restructure procurement and armament production at various times but without any major success. In the 1940s, for example, the armament policy was centralised under one ministry. Thereafter, the responsibility was handed over to three different ministries, each dealing with the army, navy and the air force. This led to ad-hocism and duplication in research and production efforts, with the industrial entities often offering “dissimilar solutions for similar problems and demands”. To arrest this trend, the post of Chief of Defence Staff (CDS) was created in 1948 and the services were tasked to report to him about their procurement plan. This did not improve matters as the industry “was not in synchronisation with the services”. Even as late as in the 1950s, the situation was still “characterised by a multitude of projects and prototypes, and of inter-service rivalry as well as intra-services isolation.”9 The French aerospace industry, which is now a major success story, was not internationally competitive way back in 1950.

Note: CEMA is responsible for “capability related decisions (both in terms of requirements and deployment)” whereas the SGA is responsible for “matters relating to budget, legal affairs and other support functions”. Source: DGA; and Review of Acquisition for Secretary of State for Defense: An Independent Report by Bernard Gray, p. 222.

The formation of the DMA/DGA was not without its problem of turf wars. The services, resenting a dwindling of their importance vis-à-vis the new agency, made fictitious complaints about the poor performance of tanks, vessels and aeroplanes.10 But De Gaulle had made his intent clear to the recalcitrant elements by placing the new agency’s head above any other civil or military officer in the hierarchy of the defence ministry.11 His prime motivation in creating a centralised procurement agency was rooted in his political ambition of achieving what many analysts say was a “small-scale version of a superpower status”, for which self-reliance in arms, particularly nuclear weapons, was the prime consideration.12

Since the late 1990s, owing to budget pressure and privatisation and Europeanisation of many industrial entities, the DGA has moved from performing its traditional role as a “project architect” to that of a “project manager”.

The merger of the various directorates into one agency required a “fundamental unification of the French Ministry of Defence and resulted in structures that have remained essentially the same to this day”13 even though the organisation has undergone several rounds of reforms over the years. Since the late 1990s, owing to budget pressure and privatisation and Europeanisation of many industrial entities, the DGA has moved from performing its traditional role as a “project architect” to that of a “project manager”.14 It has shed many of its original roles of designing and manufacturing weapons on its own to assume a role of actively managing industry and technology through efficient methods of contracting. It has nonetheless retained a great deal of expertise in independently evaluating weapon systems through a nation-wide network of testing centres.

The DGA has three primary missions: (i) equipping the armed forces; (ii) preparing the industry to meet future requirements, and (iii) promoting arms exports. With regard to equipping the armed forces, the DGA is responsible for design, acquisition and evaluation of the systems while working on a principle of the “entire life of the programmes”. For preparing the industry to meet future requirements, the DGA is responsible for assessing future threats and risks and setting the technological and industrial goals to meet those contingencies. In these efforts, the DGA identifies the key technologies and provides R&D funding to the industry/university/science and technology centres for development. Its R&D assistance to the industry for futuristic technology development amounted to €727 million in 2015. The mission of promoting arms exports has probably been the greatest symbol to the rest of the world of DGA’s success story. Its export order amounting to over €16 billion in 2015 far exceeded the €11 billion that France spent in procuring weapons for its armed forces. The French defence industry earns anything between 25 and 40 per cent of its turnover from exports.15

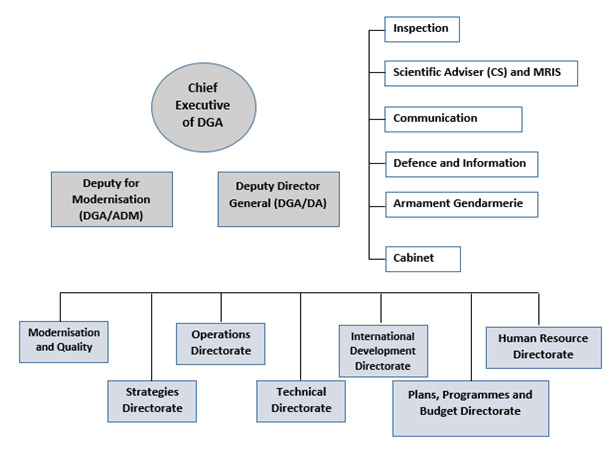

The DGA’s organisational strucure reflects the aforementined objectives with an arrangment that is divided into various directorates and enabling layers (see Figure 2 and Annexure). The Operations Directorate is the largest and deals with delivery of weapons. The Directorate for International Development is responsible for international colloboration and exports. The Directorate for Modernisation and Quality is principally responsible for test evaluation of equipment before their induction. In 2015, it conducted about 6.5 million hours of test evaluations.

Figure 2. Organisation Chart of DGA

What Makes the French System Special

DGA has several distinctive features that make it special. Foremost is its unique standing in the French governmental system. The DGA chief reports directly to the defence minister. This makes DGA loyal to the defence minister, and, in turn, to the prime minister and the president.16 Within the defence ministry, the DGA chief, who since 1977 is though technically in the same rank as the top military leadership, enjoys more powers in so far as the weapons programme is concerned. DGA’s direct reporting to the higher political authority and its supremacy over the military in the weapons programme is a rare phenomenon. This gives the agency a “tremendous prestige within the French Government”,17 which in turn helps it attract the “nation’s best and brightest scientific engineering talent”.18 As discussed later, it is this talent base that enables DGA to perform exceptionally well.

Dear Sir,

I read with interest your article. But I think you seem to ignore important points that can explain the specificity of the administrative organization of defense in France. First at the DGA there is a high concentration of highly skilled engineers coming from the best engineering schools in France. Last but not least, at the level of Army in France there is an integral Staff which is not the case in India. This is may be one of the great weaknesses of the organization of Defence in India.

Administration to be effective must be well organized. This is not the case in the context you mention. The DGA was founded in the 60s, so she has a good expertise of the equipment problems, related to the French Army. In the Indian context, we have no overall reflection related to defense issues. We have misused skills and all this lack of coordination.

Of course we must study the models of organization of defense administrations (although this should have been done long ago!). But we must first become interested in the place of the defense in the context of India .It would be useful to re-read THUCIDIDE or KAUTILYA. The concerns related to defense, security should be taught at school where we learn to become citizens!

What does it profit to have on paper a good organization of the defense, if it does not gather both men and women motivated?

Sougoumar Mayoura from Paris

I would not buy any scorpions from the French or any other Submarines.

prem

In my view the comparison of France and India in defence matters is unwarranted. France being part of Europe benefits enormously from the entire European industrial setup and expertise, which present India cannot match. Serge (not Marcel) Dassault has designed and fabricated some unique signal processing circuitry true, then again many other parts of French military electronics come from other sources around. The avionics to my information has been a joint development with the British. I fail to see how any benchmark can be set for the procurement process in any nation. Each has its own threat environment and perception and forward planning, and “procurement” needs to be tailored for that purpose. Hence what structure could be “good” for one cannot be “good” for the other, whatever that “good” criterion may be.

Nice analysis. However the Indian Army is huge. The people who tenant appointments at various levels are poorly selected. It’s not that we do not have the professional calibre. The system may be an issue but the implementation is a bigger one. Also the number of links needs to be lesser. We have a long supply chain and are diseased by the Bull Whip Effect due to the above.