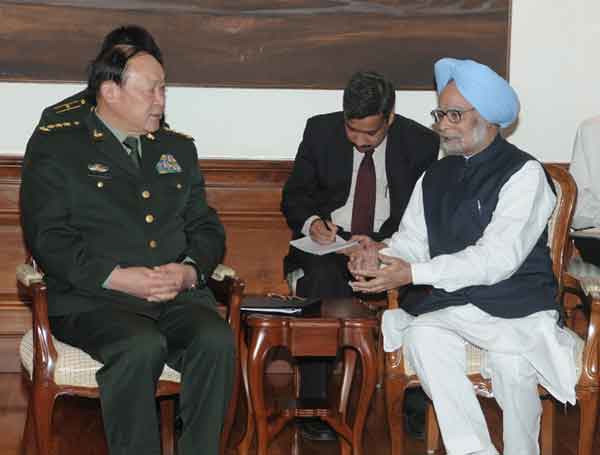

The State Councillor and Minister of National Defence of China, General Liang Guanglie calling on the Prime Minister, Dr. Manmohan Singh, in New Delhi.

The Chinese were taken completely by surprise as perhaps were our own political leaders. The then External Affairs Minister, Mr ND Tiwari was transiting Beijing on his way back from Pyong Yang after attending the Non-Aligned Coordination Bureau meeting that September, to try and assuage Chinese anger. I was accompanying him en route to Tokyo having been deputed to Pyong Yang to assist our delegation. Senior Chinese Foreign Ministry officials were at hand at the airport to receive our delegation. In the brief exchange that took place at the airport, our Minister’s protestations of peace and goodwill were met with the not unreasonable comment that while our leaders were talking peace they were making aggressive military moves on the ground at the same time. China would only be satisfied if Indian troops vacated the ridge they had occupied. China would not be fooled; it would “listen to what is said, but see what action is taken”. In later talks we agreed to vacate the heights on our side if the Chinese retreated behind the Thagla ridge, but since they were not ready to do so, we stayed put as well.

Also read: What India needs to know about China’s world view

While we may not have planned it this way, the Chinese judged our actions through their own prism: that we had countered their unexpected move by a well orchestrated counter move of our own. Subsequently, I am told, that the offensive and overbearing tone adopted by Chinese Foreign Ministry officials also changed to being more polite and civilized The next several years were spent in the two sides discussing disengagement in this sector and finally in 1992, the eyeball to eyeball confrontation was ended and a number of confidence building measures adopted.

The use of Indian soldiers in the various military assaults on China by the British and the deployment of Indian police forces in the British Concessions, may have also left a negative residue about India and Indians in the Chinese mind.

The lesson to be drawn is not that we should be militarily provocative but that we should have enough capabilities deployed to convince the other side that aggressive moves would invite counter moves. This is the reason why it is so important for us to speed up the upgradation of our border infrastructure and communication links along all our borders, not just with China.

In dealing with China, therefore, one must constantly analyse the domestic and geopolitical environment as perceived by China, which is the prism through which its strategic calculus is shaped and implemented. In 2005, India was being courted as an emerging power both by Europe and the US, thereby expanding its own room for manoeuvre. The Chinese response to this was to project a more positive and amenable posture towards India. This took the shape of concluding the significant Political Parameters and Guiding Principles for seeking a settlement of the border issue; the depiction of Sikkim as part of India territory in Chinese maps and the declaration of a bilateral Strategic and Cooperative Partnership with India. In private parleys with Indian leaders, their Chinese counterparts conveyed a readiness to accept India’s permanent membership of the Security Council, though it was not willing to state this in black and white in the Joint Statement.

Since then, however, as Indian prospects appeared to have diminished and the perceived power gap with China has widened, the Chinese sensitivity to Indian interests has also eroded. It is only in recent months that the tide has turned somewhat, when China has been facing a countervailing backlash to its assertive posture in the South China Sea and the US has declared its intention to “rebalance” its security assets in the Asia-Pacific region. There has been a setback to Chinese hitherto dominating presence in Myanmar and a steady devaluation of Pakistan’s value to China as a proxy power to contain India. At home, there are prospects of slower growth and persistent ethnic unrest in Xinjiang and Tibet. A major leadership transition is underway adding to the overall sense of uncertainly and anxiety. We are, therefore, once again witnessing another renewed though probably temporary phase of greater friendliness towards India, but it’s a pity that we are unable to engage in active and imaginative diplomacy to leverage this opportunity to India’s enduring advantage, given the growing incoherence of our national polity.

I will speak briefly on Chinese attitudes specific to India and how China sees itself in relation to India. While going through a recent publication on China in 2020, I came across an observation I consider apt for this exercise. The historian Jacques Barzun is quoted as saying: “To see ourselves as others see us is a valuable gift, without doubt. But in international relations what is still rarer and far more useful is to see others as they see themselves.” It is true that through their long history, India and China have mostly enjoyed a benign relationship. This was mainly due to the forbidding geographical buffers between the two sides, the Taklamalan desert on the Western edges of the Chinese empire, the vast, icy plateau of Tibet to the South and the ocean expanse to its East. Such interaction as did take place was through both the caravan routes across what is now Xinjiang as well as through the sea-borne trade routes across the Indian Ocean and South China Sea, linking Indian ports on both the Eastern and Western seaboard to the East coast of China. India was not located in the traditional Chinese political order consisting of subordinate states, whether such subordination was real or imagined.

In civilizational terms, too, India, as a source of Buddhist religion and philosophy and, at some points in history, the knowledge capital of the region, may have been considered a special case, a parallel centre of power and culture, but comfortably far away. During the age of imperialism and colonialism, India came into Chinese consciousness as a source of the opium that the British insisted on dumping into China. The use of Indian soldiers in the various military assaults on China by the British and the deployment of Indian police forces in the British Concessions, may have also left a negative residue about India and Indians in the Chinese mind. This was balanced by several strong positives, however, in particular the mutual sympathy between the two peoples struggling for political liberation and emancipation throughout the first half of the 20th century. To some extent, these positives continued after Indian independence in 1947 and China’s liberation in 1949 and were even reinforced thanks to Pandit Nehru’s passionate belief in Asian resurgence and the seminal role that India and China could play in the process.

When the 1959 revolt in Tibet erupted and the Dalai Lama and 60,000 Tibetans sought and received shelter in India, the differences between the two sides on the boundary issue, took on a strategic dimension…

However, such sentiments were soon overlaid by the challenges of national consolidation in both countries and the pressures of heightened Cold War tensions. With Chinese occupation of Tibet in 1950, India and China became contiguous neighbours for the first time in history. When the 1959 revolt in Tibet erupted and the Dalai Lama and 60,000 Tibetans sought and received shelter in India, the differences between the two sides on the boundary issue, took on a strategic dimension, as has been pointed out most recently by Kissinger in his book On China. The 1962 War was not so much about the boundary as it was a Chinese response to a perceived threat to China’s control over Tibet, however misplaced such perception may have been. The comprehensive defeat of Indian forces in the short war and the regional and international humiliation of India that followed, allowed China to conveniently locate India in its traditional inter-state pattern, as a subordinate state, not capable of ever matching the pre-eminence of Chinese power and influence. Since 1962, most Chinese portrayals of India and Indian leaders in conversations with other world leaders or, more lately, in articles by some scholars and commentators, have been starkly negative. An Indian would find it quite infuriating to read some of the exchanges on India and Indian leaders in The Kissinger Transcripts. In recent times, Chinese commentaries take China’s elevated place in Asia and the world as a given, but Indian aspirations are dismissed as a “dream”. There are repeated references to the big gap between the “comprehensive national power” of the two countries. India’s indigenous capabilities are usually dismissed as having been borrowed from abroad.

In an interesting research paper entitled Chinese Responses to India’s Military Modernization, Lora Salmaan refers to the “over confidence” phenomenon that characterises Chinese comparisons of their own capabilities vis-à-vis India. She points outs that Indian claims of domestic production and innovation are frequently dismissed by Chinese analysts by adding the phrase “so-called” or putting “indigenous” or “domestic” under quotes. She concludes that “These rhetorical flourishes suggest elements of derision and dismissiveness in Chinese attitudes towards India’s domestic programmes and abilities.” This dismissiveness also colours Chinese analysis of Indian politics and society.