The Indus Basin Irrigation System (IBIS)

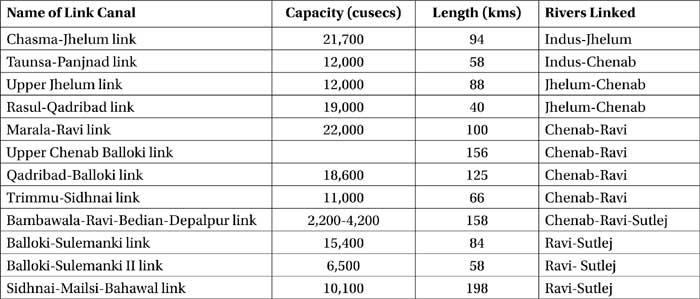

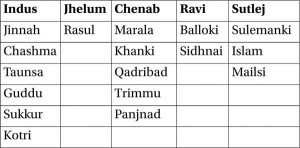

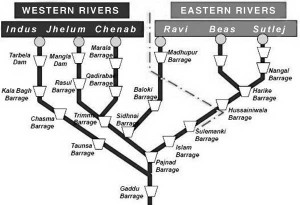

Pakistan linked its rivers through a canal-link system. Canals were taken out from the rivers, through dams and barrages. At the time of the partition of India barrages existed at Madhopur and Hussainiwala in India, while Pakistan had the Kalabagh, Sukkur, Trimmu, Baloki, Sulemanki and Islam barrages. No storage dam existed on either side. Today, Pakistan has 3 large dams, 85 small dams, 19 barrages, 12 inter link canals, 45 canals and 0.7 million tube wells to meet its commercial, domestic and irrigational needs – one of the largest canal irrigation systems in the world. The canal links constructed are given at Table 2.

Most of the link canals are unlined. They were built at a cost of 400 crore rupees, with a total capacity of 140,000 cusecs per day, transferring 2.81 MAF of water. The length of the links is about 900 kilometres. The barrages constructed on the various rivers in Pakistan are given at Table 3.

The IBIS covers all the provinces in Pakistan. In 1993, irrigated areas in the IBIS were estimated at 13,972,500 hectares. In addition, in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, about 7,800 hectares are irrigated through pump lifts which are maintained by the Provincial Irrigation Department. In northern parts of the province, irrigation is practiced by contour channels taking-off from locally available water sources i.e. streams or springs. Most of these schemes, which cover about 26,700 hectares, are owned and operated directly by the beneficiaries through traditional social organizations. In Balochistan, about 50,000 hectares are irrigated from about 800 underground channel tapping aquifers and from perennial springs. They are small group-operated schemes, with sizes ranging between 50 and 400 hectares. In addition, about 130,000 hectares of group-operated schemes are irrigated from infiltration galleries or small weirs in rivers, and about 130,000 hectares are irrigated by tube-wells and 10,000 hecatres from open wells.

Due to inadequate water availability in winter (storage capacity is too small) and at the beginning and end of summer, cropping intensity is exceptionally low.

Spate irrigation covers a total area of 1,402,448 hectares. In Pakistan, these areas are known as Rod Kohi in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Punjab, and Bandat in Balochistan, which is basically flood irrigation. Wherever possible, the runoff is harnessed for irrigation by weirs or temporary diversion structures. Farmers divert the spate flow onto their fields by constructing earth bunds (called gandas) across the rivers, or by constructing stone/gravel spurs leading towards the river. Captured water flows from field to field and when the soil is saturated, the lower bund is breached to release water into another field. The annual average cropping intensity is 20 percent.

Flood recession crop areas cover a total area of 1,230,552 hectares. In Pakistan these areas are known as Sailaba where cultivation is carried out on extensive tracts of land along the rivers and hill streams subject to annual inundation. It utilizes the moisture retained in the ground after the flood subsides together with sub-irrigation due to the capillary rise of groundwater and any rain. Apart from these water managed areas, some attempts have been made to develop water harvesting, which is known as Khushkaba. Pakistani classification of irrigation consists of:

- Government canals: 11,310,000 hectares in 1990, of which 74 percent are in the Punjab and 20 percent in the Sindh province.

- Private canals: 430,000 hectares, of which 86 percent are in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.

- Tube-wells: 4,260,000 hectares, of which 92 percent are in Punjab.

- Open wells: 280,000 hectares, of which 82 percent are in Punjab.

- Tanks: 60,000 hectares, all of them in Punjab.

- Other means: 620,000 hectares, of which 73 percent in Sindh.

- In 1989, 305, 231 tube-wells were used for irrigation in Pakistan, most of them privately owned.

The total water managed area of 16.96 million hectares is higher than the total cultivated area (16.56 million hectares). This is due to the fact that not all the water managed areas are actually cultivated. This is especially the case for spate irrigation and flood recession cropping areas. Due to inadequate water availability in winter (storage capacity is too small) and at the beginning and end of summer, cropping intensity is exceptionally low.

Statistically, the details are:

- Irrigated Area – 36 million acres (14.56 million hectares)

- Length of Canals – 56,073 kilometres

- Length of Water Courses – 1.6 million kilometres

The IBIS is characterized by its supply-based structure. It was designed to distribute water with minimum human interference. There are few structures to regulate canal flow. No escapes are provided at the tail end of the system and the surplus flows have to be absorbed within the systems. Drain construction has not kept pace with requirements, while infrastructure development has often obstructed natural drainage flows. River water, diverted by barrages and weirs into main canals and subsequently branch canals, distributaries and minors, flows to the farm in watercourses (there are over 107,000 watercourses) which are supplied through outlets (moghas) from the distributaries and minors.

The issue of water is emotive, touching people across Pakistan in a much more fundamental way than the demand for Kashmiri self-determination. Per capita water availability has fallen precipitously over the past few decades, due to rising population and poor water management…

The mogha is designed to allow a discharge that self-adjusts to variations in the parent canal. Within the watercourse command (an area ranging from 80 to 280 hectares), farmers receive water proportional to their land holding. The entire discharge of the watercourse is given to one farm for a specified period on a seven-day rotation. The rotation schedule, called warbandi, is established by the Provincial Irrigation Department, unless the farmers can reach a mutual agreement. (The warbandi is a system of water sharing prevalent in northern India and Pakistan where irrigation water is supplied according to crop assessment, size of landholding and cropped area. It is provided on an announced schedule, which changes from season to season depending on water availability).

In sum, 92 percent of Pakistan’s land area is arid or semi arid. The Indus Plain covers about 25 percent of the total land area and most of the irrigated agriculture takes place in this area, which now supports 65 percent of Pakistan’s population. The irrigated area, which is about 80 percent of the total cultivated area, produces 90 percent of Pakistan’s food requirements. 25 percent of Pakistan’s GDP comes from agriculture. While the realities of water availability, water regime, climate and delta conditions have changed, the demand for more and more water for agriculture continues to grow in most parts of Pakistan. This necessitates that the canal water management system be revisited and possible improvements carried out. Increasing population requires that crop production from irrigated areas needs to be enhanced by as much as 40 percent by the year 2025. Pakistan is using 97 percent of its surface water resources and mining its groundwater to support one of the lowest productivities in the world per unit of water and per unit of land.

The Problems

Pakistan has a population of 165 million, of which 98 million rely on agriculture. 49 million are below the poverty line and 54 million do not have access to safe drinking water, while 76 million have no sanitation.

According to the United Nations and World Bank, Pakistan’s deficit in grain production in relation to population is predicted to reach 12 million tons by the year 2013. Water availability went down to 1500 cubic metres in 2002, making Pakistan a water-stressed country and water scarcity (1000 cubic metres) is expected to be reached in 2025. Water and food security are, therefore, Pakistani’s major issues. Statistics for productivity in usage of water are given at Table 4 for purposes of comparison.

The issue of water is emotive, touching people across Pakistan in a much more fundamental way than the demand for Kashmiri self-determination. Per capita water availability has fallen precipitously over the past few decades, due to rising population and poor water management and is expected to fall below 1,000 cubic metres by 2025 — the international marker for water scarcity. In most years, the Indus barely makes it beyond the Kotri barrage in Sindh, leading to ingress of sea water, increase in soil salinity and destruction of agriculture in deltaic districts like Thatta and Badin. The current situation with regard to the degradation of the agricultural resource base is:

- 38 percent of Pakistan’s irrigated lands are waterlogged and 14 percent is saline.

- Only 45 percent of cultivable land is under cultivation at a given time.

- Salt accumulation has invaded the Indus basin and there is saline water intrusion into mined aquifers. Sea water intrusion has reached 225 kilometres inland.

Pakistan’s obsession with water must be understood in the context of the tremendous importance of the rivers of the Indus Basin for the survival of Pakistan and parts of Northern India. Though Pakistan’s water woes predate recent hydroelectric projects like Baglihar in Jammu and Kashmir, jihadi organisations have started blaming India for the growing shortage of water. Apart from inflaming public opinion against India, this propaganda helps to blunt the resentment Sindh and Balochistan have traditionally had — as the lowest riparian in the Indus river basin — against Punjab for drawing more than its fair share of the water flowing through the provinces. The campaign also deflects criticism of Pakistan’s own gross neglect of its water and sanitation sector infrastructure over the past few decades.

Pakistan’s obsession with water must be understood in the context of the tremendous importance of the rivers of the Indus Basin for the survival of Pakistan and parts of Northern India.

At the same time, the fact that river flows from India to Pakistan have slowly declined is borne out by data on both sides. Above Marala on the Chenab, for example, the average monthly flows for September have nearly halved between 1999 and 2009. India says this is because of reduced rainfall and snowmelt. Pakistan links reductions in flows to hydroelectric projects on the Indian side. Pakistani officials from time to time accuse India of violating the IWT. India denies this and there is, in any case, a system of international mediation built into the IWT for binding international arbitration if the two countries cannot resolve a water-related dispute. Pakistan invoked this mechanism for Baglihar in 2005, though the arbitrator ruled in favour of the project subject to certain modifications. An earlier dispute over the Salal project was resolved in the 1970s. Today, nothing prevents Pakistan from referring any or all of the projects India proposes to build on the Chenab and Jhelum rivers for arbitration. Mercifully, there have been no accusations of ‘water theft’ by India.

Though the treaty has a mechanism to ensure compliance with the stipulated partitioning of rivers, a major weakness from Pakistan’s standpoint is that it does not compel or require India to do anything on its side for the optimum development of what is, after all, an integrated water system. Inflows to Pakistan depend not just on rainfall and snowmelt in India and China (the uppermost eastern riparian) but also on the health of tributaries, streams, nullahs and aquifers as well as groundwater, soil and forest management practices. This is a classic problem. Costs incurred by the upper riparian on responsible watershed management produce disproportionate benefits for the lower riparian, so they are not incurred.

The IWT anticipated the importance of cooperation with Article VII stating that both parties “recognise that they have a common interest in the optimum development of the rivers, and to that extent, they declare their intention to cooperate, by mutual agreement, to the fullest extent”. So far, little has been done by either side to develop this mandate.

Costs incurred by the upper riparian on responsible watershed management produce disproportionate benefits for the lower riparian, so they are not incurred.

Today, both countries are facing the same problems with irrigated agriculture, i.e. waterlogging and soil salinity. Over the past 20 years, groundwater use has been a major factor in increasing agricultural production. Tube-wells not only supply additional water but have provided flexibility to match surface water supplies with crop water requirements. However, because of uncontrolled and rapid development of groundwater (six percent annual growth), there is a danger of excessive lowering of water tables and intrusion of saline water into freshwater aquifers. Within the IBIS, total water availability at the farm gate has significantly increased in the last 15 years, and changed slightly in its composition, with a higher use of groundwater extracted by tube-wells. In 1975, surface water represented 70 percent of the total water available, groundwater provided through private tube-wells 22.5 percent and through public tube-wells 7.5 percent. In 1990, the figures were 63 percent, 27 percent and 10 percent respectively. It has been estimated that the average water losses from canal head to outlet are 25 percent, and from outlet to farm gate are 15 percent in Pakistan.

The increasing diversion of river flows has significantly changed the hydrological balance of the irrigated areas in the past century. Initially, irrigation systems were developed without any provision for drainage. Seepage from irrigation canals and watercourses, and the deep percolation of this water have gradually raised the groundwater table, causing water-logging and salinity. It is estimated that about 2.39 million hectares had water tables within 1.5 metres of the surface level in June 1989 (which resulted in 4.92 million hectares in October 1989, just after the monsoon season). Such areas are “disaster areas” and need high priority for drainage. According to the Soil Survey of Pakistan (1985-1990), 1.78 million hectares are considered as severely saline and 0.18 million hectares as very severely saline, but the survey does not indicate which part is due to irrigation.

There is also a dispute between the provinces of Pakistan as regards sharing of the Indus waters. An accord was reached in 1991 based on the availability of 114.35 MAF per year, with a 3 MAF estimate for un-gauged canals. Though availability varies from year to year it is normally less than 117.35 MAF. The division among the provinces is at Table 5. (There is a demand of Sindh for a 10 MAF provision for downstream flow is, but this is not yet finalized).

The waters of the Sutlej are allocated to India under the Indus Waters Treaty between India and Pakistan. The annual flow of the river is around 14 million acre-feet (MAF) in the upstream of Ropar barrage located across the Sutlej River downstream of the Bhakra dam.

Looks good plan of India to destroy Pakistan using water terrorisim….but

In sha Allah this will not be happened as Allah is with us and Pakistanis will give their last drop of blood to stop India doing water terrorism against Pakistan. India has started all types of terrorism in Pakistan….heavily in Kashmir, Baluchistan and rest of Pakistan. We not cowards like you…that stop basic needs of human i.e. water…. if it continues then you will see In sha Allah that we’ll fight and give you a life long learning lesson….

We needs to revisit the IWT to choke Pak. Before doing so wee need to designate Pak a terrorist state and to withdraw MFN status to Pak to further our stand in case of any arbitration. If China intervene in the issue by threatening to stop water flow from Brahmaputra, we may demand an assurance from China regarding the flow of Brahmaputra water.

India fighting a diplomatic war to put economical sanction to Pakistan to cripple Pakistan economy that is good. But Why India does not block or divert water by abrogating IWT (Indus Water Treaty) as we know treaty are honored b/w friends not enemy. Pakistan is India’s enemy since 1947, trains, weaponized and infiltrates terrorists to kill Indian nationals.

If IWT is abrogated then entire Pakistan economy will collapse and all hydro power generation will be destroyed and thousands of Pakistani will go jobless. Pakistani security is not superior to Indian security abrogate IWT and let famine and starvation hits Pakistan. Due to weak economy Pakistan cannot handle Baluchistan freedom fighters/ guerrilla fighters as well

Be like Israel and carry out surgical strike as well otherwise BJP will have no face to public.

When we start implementing the 1960 Indus water treaty “The treaty has Annexures A through G, out of which D lists what hydroelectric projects may be constructed and operated and E lists what storage is agreed upon upstream in India. The permissible 3.6 MAF is actually a huge amount,” It amounts to 4.44 billion cubic meters / kiloliters. As a scale factor, consider that the average domestic water tank is no bigger than 2 kiloliters. No storage has been developed so far. If we start implementing the storage facility the Pakistan farmers will not get sufficient water and the people of Pakistan will turn against the Pakistan Army like what happened in Bangladesh in 1971. So we do not require any Nuclear weapon to defeat Pakistan. This is a better sanction than anything else.

Alas! Such a Cheap mentality people are still living in the word.

India fighting a diplomatic war to put economical sanction to Pakistan to cripple Pakistan economy that is good. Why India does not block or divert water by abrogating IWT (Indus Water Treaty) as we know treaty are honored b/w friends not enemy. Pakistan is India enemy since 1947.

If IWT is abrogated then entire Pakistan economy will collapse and all hydro power generation will be destroyed and thousands of Pakistani will go jobless. Pakistani security is not superior then Indian security. Due to week economy Pakistan cannot handle Baluchistan freedome fighters/ guerrilla fighters as well

Be like Israel and carry out surgical strike as well otherwise BJP will have no face.

Before the British handover of Hong Kong back to China in 1997, it was always thought that the easiest way for the Chinese to get back HK would be to turn the TAPS off as most of the water supply came from China. However, the handover was amicable. For Pakistan to use TERROR as an instrument would not work if India slows or stops the water/rivers flowing into Pakistan. It would be in Pakistan’s interest to distance itself from the terror outfits and sit down with India to settle the matter amicably before it is broken up by India. War will be useless option. Better to hand over the terrorist leaders and Dawood wanted by India!