The government of the day must take the country out of its asphyxiating bureaucratisation that seriously afflicts its defence production segment. The UK did it in the 1980s by privatising British ordnance factories. This really turned around their performance in terms of cost, quality, timeliness and global competitiveness. ‘Make in India’ in defence manufacturing, to be truly vibrant, has to consider privatisation in its production set up in a significant way. A beginning has been made in surveillance vessels. Time for big bang reforms and a change in mindset is long overdue. The great economist Keynes had aptly observed, “The difficulty does not lie in introducing new ideas but in replacing old ones.” The present government must clear the cobwebs of palpable inefficiency and lack of accountability that dogs the DPSUs and OFs and inculcate private sector dynamism into its ‘Make in India’ momentum.

India is uniquely perched to become a global manufacturing hub, should it embrace these global lessons and put in place the structural changes…

India has a large defence manufacturing base of nine Defence PSUs, 40 Ordnance Factories (OFs) and 52 laboratories with the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO). India’s self reliance index i.e. share of imports in value to total defence acquisition, is at a stagnant level of 30 per cent. This paper seeks to bring out the military industry capability in terms of manufacturing, research and development and the impact of liberalisation that has wafted through the private and public sector. It brings out the major policy changes in Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), leveraging big acquisition to gain key technologies and the need to usher in further structural changes to bring up military industry capability, design and research based on best global practices. India is uniquely perched to become a global manufacturing hub, should it embrace these global lessons and put in place the structural changes.

India’s Defence PSUs/OFs

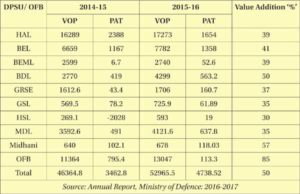

India’s Defence PSUs and OFs account for nearly $8.3 billion in terms of Value of Production (VOP) details of which along with profit after tax and value addition by each entity is represented below.

It would be seen from the above, that the VOP of the Defence PSUs and OFs has gone up by 14 per cent and the profit after tax is around 8.9 per cent. However, it must be added that the profit earned by them is due to their monopolistic character and lack of competition from the private sector. The other point to be noted is to the aspect of value addition. While in case of shipbuilding and aircraft, the value addition is around 35 per cent, it is very high in case of strategic materials and missiles produced by Midhani and Bharat Dynamics Limited (BDL) respectively. The high level of value addition in OFs (85 per cent) is predominantly due to their low technology content and complete Transfer of Technology (ToT) absorption. In contrast, in case of fighter aircraft, frigates and submarines, the DPSUs are still assemblers of sub-systems without significant value addition from the component stage.

India embarked upon economic liberalisation in 1990 by freeing the economy from the shackles of licence, quota and permit raj…

Liberalisation in Defence Manufacturing

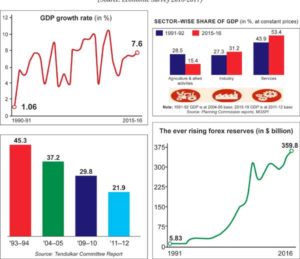

India embarked upon economic liberalisation in 1990 by freeing the economy from the shackles of licence, quota and permit raj. This unleashed high momentum of growth in terms of increase in GDP, saving, exports and Foreign Exchange (FE) reserves. It also freed the financial sector from the monopoly of public sector banks and brought in a whiff of fresh air in banking services. The impact of economic liberalisation is tabulated in figure 1.

The monopoly of Defence PSUs and OFs was done away with in 2001, when 100 per cent participation by the private sector and 26 per cent FDI was allowed. The Kelkar Committee (2005) was a major watershed, as it championed private sector participation, Public Private Partnership, a level playing field for the private sector and joint participation in R&D projects.

Fig-1: Impact of Reform on Growth, Poverty, Sector & FE Reserves (Source: Economic Survey 2016-2017)

This Committee also mooted the idea of an offset policy practiced by many countries where it could leverage big ticket acquisitions to get critical technology, FDI and outsourcing orders from the Original Equipment Manufacturers (OEMs). Subsequently, the Prabir Sengupta Committee (2006) coined the concept of Rakhya Utpadan Ratnas (RUR), as per which 12 companies were identified to have the same status as Navratna PSUs such as the HAL and BEL. This was to provide level playing field to major private sector players such as Tatas, L&T, M&M, Godrej & Boyce and Pipavav Shipyard, who are active in the defence sector, with significant investments.

However, this laudable initiative could not be progressed further as there was a perception that many large IT companies have been overlooked and a few have been favoured. The Strategic Partnership (SP) model proposed by the Dhirendra Singh Committee (2015) drew its inspiration for the ‘RUR’ model of 2006 of Prabir Sengupta. Dhirendra Singh’s model, has not received the kind of enthusiastic patronage from the Indian industry as it should have. This is because it has proposed to limit the SP to one segment only. This will limit the potential of major conglomerates such as the Tatas & L&T who can operate in several segments such as aircraft, warship, command, control and communication, to one sector only. The VK Aatre Committee (2016) also has not received enthusiastic response as it has restricted the participation of private players to one segment only. Many private players want to operate in several synergistic sectors. Any policy that preempts such opportunity would be self defeating.

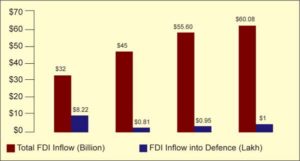

A close look at the total FDI inflow into all the sectors and inflow into the defence sector clearly underlines the urgent need to further unshackle the FDI policy in defence sector…

Major Policy Changes

FDI Policy: To the credit of the present NDA government, it has liberalised 87 rules cutting across many sectors to spur economic growth. Some of the sectors where it has been radically overhauled are construction, retail trading and food processing. In the defence sector, the present government has tried to unshackle the FDI limit by increasing it to 49 per cent from the earlier 26 per cent. However, a close look at the total FDI inflow into all the sectors and inflow into the defence sector clearly underlines the urgent need to further unshackle the FDI policy in defence sector. The inflow is really a trickle and that too from three countries viz UK, France and Israel.

It may be recalled that India’s telecom sector got a real boost due to 100 per cent FDI being allowed. The increase the FDI limit to 49 per cent in defence is ineffective. The inflow into the defence sector has been tepid so far and there is a need to increase it beyond 50 per cent, so that OEMs and design houses will like to have long-term investment in India and make India a preferred destination as a manufacturing hub with major stockholding. They will pass on critical state-of-the-art technology.

The experience of countries such as China, which has become the manufacturing hub for aircraft like Boeing, is a testimony to the realism of Chinese as they have increased the FDI limit for foreign players beyond 50 per cent. The fear that increasing FDI limit beyond 50 per cent will affect India’s sovereignty is misplaced as suitable legal safeguards can be put in place to preempt flight of capital and repatriation of profits.

Offset Policy: A major defence policy termed as the Offset Policy was announced in 2005 for leveraging India’s big ticket acquisitions to get critical technology and outsourcing orders from the OEMs who have bagged the export orders. This policy has been subsequently amplified in its scope by including multipliers for critical technology, incentivising SMEs and allowing products having dual use in paramilitary and the defence sector the benefit of offset. However, such policy changes have not brought in critical technology except orders for outsourcing low-tech work by the OEMs.

For the offset policy to be effective, it has to be complemented by a liberal FDI policy where the OEMs can be major stakeholders. Brazil’s experiment of building Embraer aircraft through technology transfer by USA was highly successful as the government provided full support in terms of galvanising the scientific pool of the country and providing tax holidays. The mosaic should be widened to include ‘indirect’ offsets, which will include other social sectors such as education, health and infrastructure instead of being defence specific only. Many countries allow indirect offsets to improve their education and health footprint. India must adopt best global practices in offset policy to build state-of-the-art systems and platforms, as countries like Brazil have done, by availing state-of-the-art technology and fostering long-term partnership with OEMs.

There is a need to make significant changes in the organisational structure of the Ministry of Defence (MoD)…

Need for Structural Changes

There is a need to make significant changes in the organisational structure of the Ministry of Defence (MoD) based on best global practices as in France and USA.

• Director General of Armaments (DGA)

It was created in 1961 in France with a view to providing a collaborative platform in which research, design, manufacture and maintenance by different stakeholders are monitored by the DGA. It has been able to provide unique solution for maintaining combat worthiness of the French defence while ensuring competitiveness, quality and safety of defence platforms.

In India, the different stakeholders such as the services, production organisations, the DRDO and the private sector player’s work in silos. The MoD, which should provide a coordinating platform to the different agencies, is unable to provide the leadership which DGA provides. The MoD is run by civilians who do not have the requisite specialised professional expertise in the defence sector and are unable to provide the much-needed strategic thinking and professional expertise required at the apex level.

• Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA)

DARPA was created in the US in 1958 in response to the technological surprise which was sprung by the then USSR by sending the Sputnik into space. DARPA seeks to avoid technological surprise from other countries and formulates research and development projects to expand the frontiers of technology beyond immediate military requirement. With very active participation from the industry, DARPA has been a frontrunner in developing state-of-the-art, military technology like super computers, stealth aircraft and Electronic Warfare (EW) systems. It has gone beyond pure military requirement to developing non-military products like computer networking that has made the US the leading IT super power in the world.

The private sector is still not sure as to how technology transfers from OEM and design houses will pan out…

Challenges of Strategic Partnership

The Dhirendra Singh Committee had rightly underscored the importance of Strategic Partnership where a private sector player would be identified as the Production Agency for a particular deliverable/platform, either in Aeronautics, Ship Building, Armoured Vehicles, Missiles and Materials in tandem with an OEM and design house. This would take away monopoly of the defence PSUs as nominated agencies for the platform without competition. The RUR concept of Prabir Sengupta Committee was on the same lines, though it seemed to favour a few private sector players and excluded the major players in the IT sector.

Dr Aatre, retired SA to RM, provided some guidelines on how to operationalise the SP concept. Though laudable as an idea, SP in India will never be realised because firstly, it limits the footprint of private sector as SP to only one system like Aeronautics or naval systems. This is grossly unfair as the major private sector players have multiple capabilities, cutting across systems. Unlike the DPSUs, which are built around a single product, the major private sector players will like to enter multiple fields of specialisation. Many OEMs are also organised on the same lines.

Besides, the private sector is still not sure as to how technology transfers from OEM and design houses will pan out and what kind of role the government would play to facilitate the process. Many countries insist on a sovereign guarantee in the matter of technology transfer as they are not quite sure about the End Use and Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) compliance by private players. In the existing structure of the MoD, the Department of Defence Production overtly patronises the defence PSUs, despite myriad promises of providing a level playing field to the private sector players. The PM Nair Committee had strongly pitched for corporatisation of the Ordnance Factories in the 1980s. The government could not combat the entrenched opposition of the trade unions. The concept of SP is likeable, but is not feasible, given the structural constraints and intransigence of the present government to give Big Push in defence manufacturing.

The private sector players are also at a serious disadvantage in designing such state-of-the-art defence systems…

Build to Print or Print to Build

The ToT route of India since the 1969s undertakes production based on design and production drawings from the licensor. The value addition is generally minimal. Most DPSUs cannot even make an upgrade, as is the case with the SU-30 MKI, an aircraft where HAL has enormous production experience. HAL’s design capability remains wobbly, particularly in state-of-the-art electronics and propulsion sub-systems. The critical factor, therefore, is how to improve our design capacity in niche sub-systems.

The private sector players are also at a serious disadvantage in designing such state-of-the-art defence systems and have to earmark a significant amount of their budget to R&D and collaborate with well-known design houses globally to absorb credible design capability. One also notes with concern a tendency on the part of the government to ask private players to hand over their prototypes and design documents to DPSUs for further development and production. This is clearly a retrograde move, as the private sector designer and prototype developer would like to have its choice of the Production Agency. This is tantamount to stopping the momentum of private sector players such as the Tatas, L&T and M&M who established good rapport with OEMs in the field of Aeronautics, Naval Systems and Armoured Vehicles and Artillery systems.

The government of the day must take the country out of its asphyxiating bureaucratisation that seriously afflicts its defence production segment. The United Kingdom (UK) did it in the 1980s by privatising British ordnance factories. It really turned around their performance in terms of cost, quality, timeliness and global competitiveness. ‘Make in India’ in defence manufacturing, to be truly vibrant, has to consider privatisation in its production set-up in a significant way. A beginning has been made in surveillance vessels. Time for big bang reforms and a change in mind set is long overdue. The great economist Keynes had aptly observed, “The difficulty does not lie in introducing new ideas but in replacing old ones.” The present government must clear the cobwebs of palpable inefficiency and lack of accountability that dogs the DPSUs and OFs and inculcate private sector dynamism into its ‘Make in India’ momentum.

A revamped organisational structure, with liberal FDI and offset policy can make India a global defence manufacturing hub and be part of the mainstream to promote ‘Make in India’…

The Way Forward

Defence sectors all over the world are unique in their character as they have to contend with adversaries and protect the sovereignty of the country. Organically they have to be guided by strategies, which cannot be shared with the public at large. However, the production segment of the MoD has witnessed significant privatisation over the years in several countries. In the USA, the private sector is the predominant supplier of weapon systems, UK also chose to privatise the Royal Ordnance Factories in the 1980s to unleash a process of cost and efficiency optimisation. The R&D activities of the developed countries also have significant private sector participation.

India, in contrast, is still saddled with a huge defence public sector and Ordnance Factories which do not function optimally. The private sector was allowed into the shipbuilding sector during 2008-2009 for producing surveillance vessels. This has been a very promising development in terms of economy and timely delivery. This will need to be tried out in the aerospace sector for building Advanced Light Helicopters, trainers and transport aircraft. Both shipbuilding and aerospace have considerable potential for dual use. Furthermore, the research and development activities must go beyond government funding in Science and Technology departments namely the DRDO, BARC, Space and DST. Private sector players must earmark funds for improving their design capability. A market economy is essentially an enabler to unleash ‘animal spirits’ of the private sector. India’s defence sector must be part of this economic renaissance. A revamped organisational structure, with liberal FDI and offset policy can make India a global defence manufacturing hub and be part of the mainstream to promote ‘Make in India’.