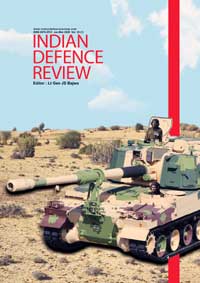

Various Unmanned Aerial Vehicles. Pictured are (front to back, left to right) RQ-11A Raven, Evolution, Dragon Eye, NASA FLIC, Arcturus T-15, Skylark, Tern, RQ-2B Pioneer, and Neptune.

Drones have been called “the ultimate military growth industry”. Air, naval and land forces everywhere are striving to acquire these platforms. Herein lies the danger; thanks to advanced armed drones, aggression is becoming pain-free. Practically every military that has inducted UCAVs has sought to purchase even more of them and employ them with increasing frequency. This is because armed drones are seen as a way to coerce the adversary without the risk of body-bags. Even the sixth-generation combat jets now in the conceptual stage, may be only optionally manned. The transformational potential of AI-endowed unmanned systems on air operations is immense. Future UAVs will be more capable than ever with higher speeds, greater ranges, more manoeuverability and more stealth than today’s systems. UCAVs will offer greater accuracy and lethality coupled with autonomy. Unmanned systems will provide the means to conduct aerial operations anywhere in the world and at any time, with or without human beings in the loop.

Although most drones are employed for ISR tasks, it is their use as Unmanned Combat Air Vehicles (UCAV) for kinetic strikes and so-called ‘targeted killings’ that regularly attract headlines…

War in the third dimension has long been fought by manned aircraft, whether of the fixed or rotary-wing variety. These are now being joined and in some cases, replaced by drones. Drones, more correctly known as Unmanned Air Vehicles (UAVs), may be remote-controlled and operated from the ground or may fly semi-autonomously based on a pre-set flight plan or may function entirely on their own, controlled only by Artificial Intelligence (AI) and dynamic automation systems. And they have the potential to revolutionise warfare.

Global drone proliferation has been rather rapid since the turn of the century. Military forces in an estimated 90 countries currently operate UAVs for anti-aircraft target practice, Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance (ISR), communications and strikes. The drones range in size from the Northrop Grumman RQ-4 Global Hawk, an unmanned surveillance aircraft with a 40m wingspan, to the Black Hornet Nano, a 10-cm military micro helicopter UAV developed by Prox Dynamics. While the former is a High-Altitude Long Endurance (HALE) platform with full-spectrum intelligence collection capability necessary to support United States (US) military forces in worldwide operations, the latter is optimised for ultra-quiet flight and can spy on the enemy by flying around walls or peering into trenches.

Although most drones are employed for ISR tasks, it is their use as Unmanned Combat Air Vehicles (UCAV) for kinetic strikes and so-called ‘targeted killings’ that regularly attract headlines. According to military analysts, ten countries have used UCAVs in combat: the US, Israel, UK, Iraq, Iran, Nigeria, Turkey, Pakistan, Azerbaijan, and the UAE. Another 10-15 nations either possess armed drones or are in the process of arming them.

With many countries striving to induct ever more advanced drones, the unmanned/manned mix of major air forces may be 50/50 or more within 20 years. That’s not all. The world is awash in cheap civilian drones, some of which rival or exceed the capability of more expensive military ones. These hold an obvious appeal for non-state actors and several militant outfits are known to have employed commercially manufactured fixed and rotary-wing drones for surveillance. A few groups in conflict zones around the world have even armed cheap consumer drones with rudimentary weapons, which is not difficult to do, and used them for attacks.

According to Stanford political scientist Amy Zegart, countries that possess armed drones could change an adversary’s behaviour without even using them…

Scholars are studying if this global drone proliferation could change the very nature of warfare. Will drones transform the future battlefield or will their impact be merely peripheral?

A Brief History of UAVs

Some historians trace the first drone strike to 1849, when the Austrian army launched 200 pilotless, bomb-carrying hot-air balloons armed with time fuses against the besieged city of Venice. However, the wind changed and brought the balloons right back over the Austrians. The Wright brothers’ first heavier-than-air manned flight happened in December 1903 and the first pilotless aircraft were built just a decade later, during the First World War. In 1935, the British developed a pilotless radio-controlled target, the DH.82B Queen Bee, derived from the de Havilland Tiger Moth biplane. The name Queen Bee probably gave rise to the use of the term ‘drone’ for all pilotless aircraft, especially when they were radio-controlled.

For many years, drones were seen as expensive and rather unreliable and their development happened only in fits and starts. Perhaps the first spectacular use of UAVs was during the Israeli Air Force’s victory against the Syrian Air Force over Lebanon’s Bekaa Valley in 1982. Israel used drones alongside manned aircraft as electronic decoys, jammers and for real-time reconnaissance.

| Pros and Cons of Drones in War

Pros • Save Lives: Drones greatly reduce the risk of injury or death to own airborne and surface personnel. • Low Cost: Cheaper to purchase and operate than manned aircraft. • Long Endurance: Can operate far longer than manned aircraft. • Systematic Surveillance: Can fly clandestinely and continuously for long periods and so gather more actionable military intelligence. • Rapid Deployment: Can be deployed and launched must faster than manned aircraft. Cons • Limited Survivability: Drones till now have featured only in asymmetric conflicts. They have yet to prove themselves against adversaries with matching capability. • Prone to Accidents: Drone crashes due to human error or technical failure are fairly frequent. • Limited Automation: Today’s drones are heavily dependent on links with their controllers. A drone whose link has failed is in big trouble. • Incapable of Value Judgements: Airborne pilots can keep the overall situation in mind and decide not to attack, whereas drone strikes may cause unintended damage to civilian lives and property. • Lower the Conflict Threshold: The ethical dimension of war may be compromised by eliminating fear of death of injury to own forces; the decision to attack becomes easy. • Attract Negative Publicity: Public opinion about drone strikes is typically negative. Targeted killings lie in a legal grey area. There are growing calls to ban autonomous strike drones. |

Drones gradually became an essential part of every modern air force’s inventory. The world’s first known drone strike by a nation occurred in Afghanistan on October 07, 2001. It was a Hellfire-missile attack by a General Atomics MQ-1 Predator operated by the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). The target was the Taliban leader Mullah Omar, but the Predator destroyed another vehicle killing several of his bodyguards and he managed to escape in the resulting chaos.

To Drone or Not to Drone?

Four characteristics of UAVs are mainly responsible for making them what they are today:–

• Their thin, long wings that give them vastly more endurance than manned aircraft.

• The use of real-time transmitters to send pictures and video footage straight back to commanders.

• The use of satellite networks rather than radio waves to exercise control across continents.

• Lastly, the fitment of weapons on some drones giving them credible strike capability.

Like any other military asset, drones have their strong and weak points (see Box). According to Stanford political scientist Amy Zegart, countries that possess armed drones could change an adversary’s behaviour without even using them. “The advent of armed drones suggests that costly signals may no longer be the best or only path to threat credibility,” she says.

Amy Zegart opines that as wars grow longer and less conclusive, a particular country’s test of resolve becomes, “more about sustaining than initiating action,” for which drones are ideally suited. She explains, “Drones offer three unique coercion advantages that theorists did not foresee: sustainability in long duration conflicts; certainty of precision punishment, which can change the psychology of adversaries and changes in the relative costs of war.” These coercion advantages are most marked in asymmetric warfare, “In situations where a coercing state has armed drones but a target state does not, drones make it possible to implement threats in ways that impose vanishingly low costs on the coercer, but disproportionately high costs on the target.” That is why drones are increasing in popularity.

The USAF is actively investigating the possibility of flying manned jets in tandem with fairly large unmanned systems…

Much of the growing body of discussion about drones relates to their now routine employment by the US for targeted killings. In countries such as Yemen and Pakistan, it would seem that such strikes have high pay-offs because a number of top leaders have been eliminated and various terror groups are now on the backfoot. But in countries such as Somalia, years of US counter-terrorism action have not succeeded in denting the al-Shabaab’s operational capability.

A deeper concern is that while drone strikes undoubtedly avoid casualties among the attacking force, the killing of hundreds of innocent civilians could spur the beleaguered societies to exact a terrible revenge at some future time. Although the US routinely dismisses criticism by human rights organisations that its drone strikes violate international humanitarian law, its own arguments could come back to haunt it when the shoe is on the other foot. In fact, the use of armed drones by militant and terrorist outfits is already a reality.

Swarm Attacks

At present, each UAV needs a separate controller. But thanks to advances in chip technology and software, it is becoming possible for simple drones to achieve mutual coordination. With scores of military technologists now working on drone swarms they could soon become the cheapest way to conduct many types of aerial missions. The hardware is already available and it may not be too long before technologists succeed in enabling a large number of individual drones to function as an integrated, cohesive unit.

Future ground forces, even infantry personnel, will make extensive use of small and nano drones…

On January 5, 2018, a Russian air base and a nearby naval base in Syria came under attack by a swarm of 13 small drones, probably operated by a Syrian insurgent group. The armed UAVs were all destroyed or forced down without casualties or damage to Russian installations. Over the last couple of years, there have also been several spectacular aerial demonstrations of hundreds of small drones dancing, blinking and manoeuvering in coordination. However, all these devices were pre-programmed or choreographed in advance.

On the other hand, in a true military drone swarm, every drone is partially or fully autonomous. One of the most significant tests of such a swarm was conducted in October 2016. In it, 103 robin-sized Perdix micro-drones were launched from three F/A-18 Super Hornet combat jets and demonstrated advanced swarm behaviour such as collective decision-making, adaptive formation flying and self-healing. According to the US Department of Defence, “Perdix are not pre-programmed synchronised individuals, they are a collective organism, sharing one distributed brain for decision-making and adapting to each other like swarms in nature. Because every Perdix communicates and collaborates with every other Perdix, the swarm has no leader and can gracefully adapt to drones entering or exiting the team.” Since then the US Defence Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) has been striving to give drone swarms the ability to work together in numbers and achieve mission objectives, even when communications are offline and GPS unavailable.

Scores of armed quadcopter drones could be simultaneously launched from vehicle-mounted canisters or deployed close to the frontline by fighter or transport aircraft, depending on the threat from the enemy’s Air Defence (AD) system. After release, they would link up and proceed to the mission area, recognise suitable targets based on complex algorithms and then mount their attack. They would be highly effective against targets such as aircraft on ground, fuel bowsers, ammunition dumps, heli-bases, radar and communication antennae, command and control nodes. Against these targets, even a small amount of precisely aimed explosive could render the system inoperative. Larger UAVs would be effective against targets such as armour and guns. Small jet-powered drones could also be launched in swarms to bring down a manned jet or transport aircraft.

Although autonomous drones can be programmed to cope with a variety of situations, they cannot handle the unexpected…

The clear advantages and rather low cost of drone swarms make them attractive even to smaller military forces. It would be difficult if not impossible, for current AD systems to counter hundreds of approaching drones. The UAVs would saturate the battlefield and swamp the available anti-aircraft resources. While some would certainly be shot down, enough might survive to regroup and successfully execute the attack.

A True Loyal Wingman

The other major trend for the coming drone wars is Manned-Unmanned Teaming (MUT) – the control of large unmanned systems from a manned aircraft. Manufacturers such as Airbus are performing flight tests to validate the concept. One demonstration consisted of five Airbus Do-DT25 target drones controlled by a mission group commander airborne in a manned aircraft. China’s Sky Hawk, one of its newest stealth drones, can also communicate and collaborate with manned aircraft for surveillance and combat operations.

But how can an already overworked pilot control a group of drones? The ability to easily and intuitively exercise control from the cockpit is the result of an advanced flight control and flight management system which combines fully automatic guidance, navigation and control with intelligent swarming capabilities on the part of the drones. A small number of manned combat jets and crew may then undertake what an entire squadron does at present. This could be a game changer for air missions such as air superiority, strike, ISR and EW. There would also be a major reduction in operations, maintenance and training costs.

The USAF is actively investigating the possibility of flying manned jets in tandem with fairly large unmanned systems. In March, it successfully tested an advanced, jet-powered drone, the XO-58A Valkyrie demonstrator, which will accompany a combat jet as a ‘loyal wingman’. The drone, which can use a conventional runway or be launched by a rocket, may be employed for EW, ISR, protecting its leader or even dropping bombs. One Valkyrie is expected to cost just $2 to $3 million against the $100 million for its lead jet.

The “box” misses out to enter in the cons list hand held jammers of the size of mobile phones which can easily confuse the attacking drones to miss their targets or become useless for gathering the intelligence information to transmit back. Also, the drones fly low and can be destroyed by ground fire or anti-aircraft guns. Thus these gadgets can be rendered virtually useless in the battle field when the defender is geared up with adequate countermeasures.