Chinese incursions have been making headlines in the Indian media. Unfortunately, the Indian leadership prefers to mitigate the facts, to not “hurt feelings of the Chinese” or “make things worse”. After all, they say, that China is our neighbour for a long time to come and we have to learn to live with it!

Foreign Minister SM Krishna articulated the government’s position: “With China, I think the boundary has been one of the most peaceful. So, there is no issue on that.” He added that there “is a built-in mechanism which is in place and which takes care of such incursions. India has so far acted with restraint, maintaining that the Line of Actual Control (LAC) with China is not very well defined.”

When the press pointed out: “But even on the maps it is shown as an undefined border.” Nehru could only say “Maybe. All these are high mountains. Nobody lives there. It is not very necessary to define these things.”

This mechanism1 seems to have given a free license for the PLA to intrude (or send grazers) into Indian territory, as in any case ‘there is a mechanism’ to sort out the problems!

This time however, the Indian Army acknowledged the facts. The Army Chief, General Deepak Kapoor admitted that India had lodged a protest with Beijing on the incursion of a Chinese helicopter into Indian territory and the painting of some rocks in red.

The Press reported that “the Army is gathering evidence from the spots where Chinese troops had painted rocks”. What does ‘gathering evidence’ mean? Does it imply that the Army is not aware of what is happening on the LAC? Perhaps, as Nehru, the first Prime Minister of Independent India said once during a press conference: “All these are high mountains. Nobody lives there.” The history of the first incursions is educative.

The beginning of the story

May 1951 was an important watershed in the history of the relations between India, Tibet and China. That month, left with no alternative, Tibetan officials signed a 17-Point Agreement2 with the People’s Republic of China in Beijing. Mao’s Liberation Army had invaded their country a few months earlier; the Roof of the World was now under occupation3 and no nation was ready to support the peace-loving Tibetans.

With the new Agreement, Tibet had become a mere ‘autonomous region’ of China; the other particularity of the Agreement was that, for the first time in fifty years, India was not a party to an accord between Lhasa and Beijing. It would have disastrous consequences for India and Tibet.Three years later, another agreement concerning Tibet (known as the Panchsheel Agreement) was signed,4 this time between China and India alone. This was the last nail in the Tibetan coffin; Delhi for the first time officially acknowledged that China was its new neighbour. In the meantime, Chinese troops had begun to trespass into Indian territory.

With the new Agreement, Tibet had become a mere ‘autonomous region’ of China; the other particularity of the Agreement was that, for the first time in fifty years, India was not a party to an accord between Lhasa and Beijing. It would have disastrous consequences for India and Tibet.Three years later, another agreement concerning Tibet (known as the Panchsheel Agreement) was signed,4 this time between China and India alone. This was the last nail in the Tibetan coffin; Delhi for the first time officially acknowledged that China was its new neighbour. In the meantime, Chinese troops had begun to trespass into Indian territory.

The Downgrading of the Mission in Lhasa

But let us go back to 1952. As Delhi started to dither on whether to address the confirmation of its borders with ‘China’s Tibet’ through bilateral talks with the Communist regime in Beijing,5 the first incursions took place through the porous border.

Ideologically, Nehru was not comfortable with the ‘imperialist’ privileges inherited6 from the British in Tibet.7 The Prime Minister had started dreaming of a great friendship with China. He wrote to the Chief Ministers: “For the first time, China possesses a strong Central Government whose decrees run even to Sinkiang and Tibet. Our own relations with China are definitively friendly.”8

By summer 1952, the Chinese were physically in control of most parts of the Tibetan Plateau; the Tibetans were discovering the hardships caused by an invading army.9 During a press conference, when asked about talks with China on the situation in Tibet, Nehru hinted at changes: “Nothing very definite has taken place yet… Obviously once it is accepted and admitted that the Chinese Government is not only the suzerain power in Tibet but is exercising the suzerainty, then something will flow from it. Then you cannot treat Tibet as an independent country with an independent representation from us.”10

As Nehru continued to backpedal, Beijing stepped up its pressure. It wanted India to downgrade the Indian Mission in Lhasa into a Consulate General.11 In June 1952 Nehru stated for the first time that “the status of the representative in Lhasa has never been defined for the last thirty years.”12

The Prime Minister explained that for him the circumstances had changed and from an independent country, Tibet had become a country under the effective suzerainty of China: “China is now exercising its suzerainty.”

In the same month, the clever Zhou Enlai told KM Panikkar, the gullible Indian Ambassador in China that he “presumed that India had no intention of claiming special rights arising from the unequal treaties of the past and was prepared to negotiate a new and permanent relationship safeguarding legitimate interests.”

Nehru explained: “The McMahon Line is the frontier, but on this side of the McMahon Line there have been undeveloped territories-jungles, etc. You take ten days to a fortnight to reach the frontier from any administrative centre.”

Nehru finally told Panikkar that Delhi had no objection to convert the Mission in Lhasa into a Consulate-General. And as a bonus the Communist regime would get a Chinese Consulate in Bombay!

He however added: “We would naturally prefer a general and comprehensive settlement which includes the Frontier.”13 This would not happen.

The Indian Representative was re-designated into a Consul-General under the Indian Embassy in Beijing. By downgrading the Mission, the Indian Government officially accepted that Tibet was a part of China; Tibet’s border was thereafter China’s border. The troubles were to start.

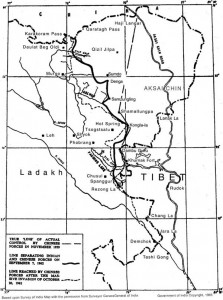

During another press conference in 195214 the Indian Prime Minister declared that he was not aware of “any infiltration of Chinese troops in India.” Rumours had begun about Chinese incursions through the UP-Tibet15 border as well as through the Ladakh-Tibet border. The first Chinese surveys for the Sinkiang-Tibet highway cutting through the Aksai Chin probably occurred during these years.

But Nehru always saw ‘larger perspectives’. Once, when S Sinha, the Indian Representative in Lhasa, asked the Ministry of External Affairs some help for the Tibetans, Nehru wrote to Sinha: “We have to judge these matters from a larger world point of view which probably our Tibetan friends have no means of appreciating.”

Indeed, the Tibetans could not understand what was happening to them.

Border Issues

A few months earlier, the issue of the border had been mentioned for the first time by the Chinese leadership. On September 21, 1951, Panikkar had a meeting with Zhou Enlai who told the Indian Ambassador: “The stabilisation of the Tibetan frontier [which] was a matter of common interest to India, Nepal and China and could best be done by discussions among the three countries.”16

In his biography of Nehru, Dr S Gopal noted: “this shrouded sentence [about the stabilisation of the border] was not an explicit recognition of the frontier.”

Also read: Low Intensity Conflict revisited

Nehru must however have sensed that something was not right, and he wrote to Panikkar: “the new situation made us somewhat apprehensive of this long frontier and we had to take some steps in regard to it. Previously we had completely ignored this frontier. Now we could not do that.”17

In February 1952, during a press conference, Nehru explained: “The McMahon Line is the frontier, but on this side of the McMahon Line there have been undeveloped territories-jungles, etc. You take ten days to a fortnight to reach the frontier from any administrative centre.”

However when the journalist pointed out the north-west sector, the Prime Minister was less assured: “I do not know. The McMahon Line is a definition of that border on the north-east.” But the journalist insisted: “There is a certain tract which is undefined so far – even on the maps it is shown as undefined18 – towards the north-east and north-west, between Nepal and the province of Kashmir: near Lake Manasarovar.” Nehru answered, “I do not know that any question has arisen; it has not come up before me at all at any time.”

And once again when the press pointed out: “But even on the maps it is shown as an undefined border.” Nehru could only say “Maybe. All these are high mountains. Nobody lives there. It is not very necessary to define these things.”

That was it!

Border infiltration in UP and NEFA

Disturbing rumours of Tibetan and Chinese infiltration through the U.P. border continued to circulate in the press and in some government circles.

In October 1951, Sampuranand, a Minister in the U.P. Government, wrote to the Prime Minister pointing out that some areas adjoining Tibet had become vulnerable “because of Tibetan activities supported by China.” He asked the Government to take necessary precautions by laying strategic roads, constructing barracks for soldiers and establishing army outposts on the Indian side. Nehru replied a few days later that India had not been entirely negligent about the Tibetan border. Various agencies had looked into the matter and “some steps have already been taken on the lines of the recommendations made.”19

Also read: India in the neighbourhood

The extent of the enquiries and who had made them20 is not very clear. It is true that a Border Defence Committee under Lt Gen. Kulwant Singh had been set up earlier and some recommendations had been given. However, very little was achieved in term of intelligence gathering and manning the border till the early sixties. Anyhow, Nehru optimistically concluded “I do not think that we need take too gloomy a view of the situation.”

We have to mention a personal anecdote. Recently while spending some leisure time in Munsyari, the last town before the Indo-Tibet border in the Kumaon Hills, we located the ‘historian’ of area. Till the 1962 War, this tehsil used to be the main centre for business with Western Tibet. Most of the Bothias, the local tribes lived on trade. Caravans used to depart from Milam, a village in Johar Valley, north of Munsyari and proceed to the trade markets around the Kailash-Mansarovar area.

In the early 1950″™s, Communist China decided to “™strengthen its border and roads were immediately constructed. In India, even though the decision had been made at the highest level, nothing happened for several years.

The old ‘historian’ told us a flabbergasting story. Lakshan Singh Jangpangi, a native to the area, had joined the Foreign Service in the forties as a senior accountant in the Indian Trade Mart of Gartok, east of the Kailash. In 1946, he was promoted to the important post of British Trade Agent. When India became independent, he continued to serve in the same position till he was transferred to Yatung in 1959. We were told that Jangpangi, who from Gartok had a panoramic view on what was going on in Western Tibet, had informed his Minister (Jawaharlal Nehru) that the Chinese had started to build on the arid Aksai Chin plateau. This was in 1951-52.

Crossing the Indian territory, the road only became the object of official correspondence with the Chinese Government seven years later. We shall come back to it.

The most ironic part of the story is that Jangpangi was awarded the first Padma Shri Award given to a Kumaoni ‘for his meritorious services’. Was it for breaking the news or for having kept quiet? We will probably never know.21

In September 1952, the Prime Minister, probably informed by Jangpangi wrote a Note to the Foreign Secretary about some alleged intrusions. He had also received a letter from Dr KM Munshi, the UP Governor, pointing out that the boundary between Tehri and Tibet was not clearly defined.

Nehru answered: “My own impression is that we are clear about the boundary. But Tibetans have regularly come across it here as well as in Assam22 and collected rent or revenue.”23

The fact that revenue was collected in some areas by the Tibetan authorities till 1951-52,24 would have very serious repercussions on the future of the border areas particularly in the Northeast, UP and Ladakh sectors. The Chinese were systematically building roads and a communication network from Lhasa to the borders of India.25 Soon they would claim as part of the People’s Republic of China, all the areas where the Tibetans had once collected (monastic) revenue, whether it was on the Tibetan or the Indian side of the McMahon Line.

Also read: Neglect of India’s frontier areas

In the central and western sectors, the situation was even more complicate, because as pointed out by Dr Munshi the frontier was not physically demarcated. Obviously, as long as there was a friendly and peaceful state on the other side of the border, it was not crucial to have a proper delineation or physical demarcation. Tibet and India had lived for millennia as neighbours and friends with no problems. But in the early fifties the situation had changed drastically.

It should be noted that in 1952 the question was only about Tibetan incursions into Indian territory. A year or two later it would be far more serious; it would be Chinese troops.

In September 1952, Nehru wrote to the Foreign Secretary to reiterate what he had earlier told Sampurnanand: “Definitely and precisely that they should not be allowed to come and they should be pushed back if they cross over.”

He admitted he had not followed up on the matter: “what happened later, I do not know.” The UP Government was ready to keep some armed police on the border provided that the Centre put up some barracks. Nehru added: “it was not fair to expect them to remain in tents or in the open.” Unfortunately for India’s borders, the buck was passed from one ministry to another, further from the State to the Centre and back. Finally, bureaucracy prevailed and nothing happened for one more decade.

It should be noted that in 1952 the question was only about Tibetan incursions into Indian territory. A year or two later it would be far more serious; it would be Chinese troops. Though they had never visited these areas before, their policy was clear: wherever Tibetans had made claims on Indian soil, this territory automatically became Chinese territory.

But the Indian Prime Minister saw things from a different angle. He felt that development was the only way to tackle the situation. The most important task was to ‘develop’ the border areas. He believed that the people of the border areas, if provided better opportunities would be the first to defend India’s borders. He felt that the people living close to the borders had to play an important role in the relations with the neighbour country: “while they can ensure peace in their own country, they can also create troubles”. In the same letter, he added: “Nobody need get upset over the recent developments in Tibet.”26 He repeated that one of India’s foremost interests was the cultivation of friendly relations with China and Tibet.

The manning of the border posts remained under the Ministry of External Affairs. With rumours circulating about border incursions, Nehru had to take a renewed interest in the issue of infiltrations and look at the steps necessary to control them. In March 1953, he informed the Foreign Secretary again about the difficulties experienced on the UP-Tibet border: “Two years ago or so a committee [made] certain recommendations about the steps to be taken on our frontier areas… Since then the UP Government has repeatedly written to us on this subject, but somehow the matter has got hung up between the Home Ministry and the Finance Ministry.”27

A few months later Nehru took up the matter with the Home Minister again: “this matter has been delayed very greatly, although it is of high importance. There is no doubt that it has to be done.”28

On 17 February 1953, GB Pant, the UP Chief Minister, raised the issue once more; he drew Nehru’s attention to the lack of development in the Indo-Tibet border area. The matter had been taken up with various ministries, a comprehensive scheme sent to the Planning Commission by the UP Government, but nothing resulted from this.

Also read: Politics at the cost of India’s security

Nehru regretted again the slow progress in spite of the various recommendations made from time to time. “Nothing is moving, we must get this moving… I am particularly interested in the roads, because without the roads nothing else can really be done.”

Here we see the difference between the Indian and Chinese way of functioning. In the early 1950’s, Communist China decided to ’strengthen its border’ and roads were immediately constructed. In India, even though the decision had been made at the highest level, nothing happened for several years. Files were stuck again and again in a bureaucratic morass.29

Debate in the Parliament

In March 1953, Dr Syama Prasad Mookerjee, leader of the Hindu Mahasabha, told the Parliament: “some of our frontiers on the northern side, namely the impregnable Himalayas, have today broken down and there is no reference in the Report [Annual Report of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs] as to what steps the Government are taking for the purpose of [the] securing strategic importance of that particular area. These are matters which vitally concern us.”

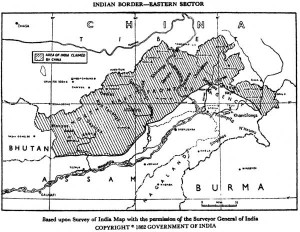

The matter was again raised during a debate in Parliament at the end of 1953. A member, Dr. Lanka Sundaram referred to the news about ‘percolation’ of Chinese troops on the Indo-Tibetan border across various passes. He claimed that 60,000 to 100,000 Chinese troops were poised across the Himalayan border, and expressed concern over the Government’s inadequate security measures. He also pointed out India’s special responsibility towards Bhutan, Sikkim, Nepal and Tibet, and referred to the existence of a note in the External Affairs Ministry in which it was mentioned that China was disinclined to accept the McMahon Line.He moved an amendment pressing for the strengthening of national defence. Though the amendment was later withdrawn, Nehru replied to Dr Lanka Sundaram on December 24, 1953: “Now, Dr Lanka Sundaram gave some facts which rather surprised me. I do not know where his information comes from about the happenings on the Indo-Tibetan border. He said that 100,000 or, I forget 50,000, troops are concentrated there. I have a few sources of information too, but I have not got that information. …I am in intimate touch this way and that way on the border, on both sides, and those figures which he mentioned, so far as I am concerned are completely wrong, and far out from truth.”32

The matter was again raised during a debate in Parliament at the end of 1953. A member, Dr. Lanka Sundaram referred to the news about ‘percolation’ of Chinese troops on the Indo-Tibetan border across various passes. He claimed that 60,000 to 100,000 Chinese troops were poised across the Himalayan border, and expressed concern over the Government’s inadequate security measures. He also pointed out India’s special responsibility towards Bhutan, Sikkim, Nepal and Tibet, and referred to the existence of a note in the External Affairs Ministry in which it was mentioned that China was disinclined to accept the McMahon Line.He moved an amendment pressing for the strengthening of national defence. Though the amendment was later withdrawn, Nehru replied to Dr Lanka Sundaram on December 24, 1953: “Now, Dr Lanka Sundaram gave some facts which rather surprised me. I do not know where his information comes from about the happenings on the Indo-Tibetan border. He said that 100,000 or, I forget 50,000, troops are concentrated there. I have a few sources of information too, but I have not got that information. …I am in intimate touch this way and that way on the border, on both sides, and those figures which he mentioned, so far as I am concerned are completely wrong, and far out from truth.”32

The matter was yet again discussed in March 1954 while negotiations on the Panchsheel Agreement were going on in Beijing. Once more, Nehru tried to pacify the members: “Yesterday some of our friends here raised the subject of our borders, particularly on the Tibet side, what is known as the McMahon Line. I do not know why they had this sudden doubt because the McMahon Line constitutes India’s border at the moment on which we have a number of established check posts. And as far as we are concerned it is our border and will continue to be so. There is no dispute with any other country over this.”33

The Panchsheel and the first ‘officials’ intrusions

By the end of 1953 India had began initiating talks with the Chinese government with the view of arriving at an agreement to meet the changed situation. The rumours of incursions had made many Indian leaders distrustful of the ’special’ friendship with China.

Many asked: India offers her friendship, where are the reciprocal sentiments and actions? Is the Indian government serious about the Chinese threat?

The first Chinese incursion in the Barahoti area of Uttarakhand (then Uttar Pradesh) occurred in June 1954. This was the first of a series of incursions numbering in hundreds which culminated in the attack of October 1962.

But once again, the Indian negotiators avoided bringing the border issue to the negotiating table during the Beijing Conference which gave birth to the famous (or infamous) Panchsheel Agreement. It was not part of the agenda!34

It took less than two months after India had signed the “Agreement between the Republic of India and the People’s Republic of China on Trade and Intercourse between the Tibet Region of China and India” which included the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence as a preamble for Delhi to discover that the border problem had not been solved.

The first Chinese incursion in the Barahoti area of Uttarakhand (then Uttar Pradesh) occurred in June 1954. This was the first of a series of incursions numbering in hundreds which culminated in the attack of October 1962.

The irony of the story is that it is China which complained about the incursion of some Indian troops… on India’s territory! The Counsellor in the Chinese Embassy in Delhi wrote to the Indian Ministry of External Affairs on 17 July 1954: “According to a report received from the Tibet Region of China, over thirty Indian troops armed with rifles crossed the Niti pass on 29 June 1954, and intruded into Wu-Je35 of the Ali Area [Ngari] of the Tibet Region of China. The above happening is not in conformity with the principles of non-aggression and friendly co-existence between China and India.36

Many asked: India offers her friendship, where are the reciprocal sentiments and actions? Is the Indian government serious about the Chinese threat?

On August 27, the Ministry of External Affairs replied to the Chinese: “We have made thorough enquiries regarding the allegation made by the counsellor of the Chinese … that a unit of 33 Indians attached to the local garrison in U.P. (India) had intruded into the Tibet region of China…our further investigations have confirmed that the allegation is entirely incorrect. A party of our Border Security Force is encamped in the Hoti Plain which is south-east of the Niti pass and is in Indian territory. None of our troops or personnel have crossed north of the Niti pass.”37

Barahoti was (and is) well inside Indian territory; the exchange of notes continued during the following months. This exchange is the first of more than one thousand Memoranda, Notes and Letters exchanged by the Governments of India and China over the next ten years, published by the Ministry of External Affairs in the White Papers on China.

TN Kaul, the Joint Secretary who negotiated the Panchsheel Agreement, philosophically explained: “Territorial disputes have existed between near and distant neighbours through the ages. The question is whether they can and should be resolved by war, threat, use of force or through the more civilized and peaceful method of negotiation… Both sides still profess their faith in the Five Principles, and therein lies perhaps some hope for the future.38

Also read: Chinese avionics & missiles for Pakistan

John Lall, the Diwan of Sikkim later commented: “Ten days short of three months after the Tibet Agreement was signed, the Chinese sent the first signal that friendly co-existence was over… Significantly, Niti was one of the six passes specified in the Indo-Chinese Agreement by which traders and pilgrims were permitted to travel.”39

Looking at the way Indian diplomats were ready to bend backwards to any Chinese demands, Mao Zedong and his colleagues found more and more outstanding issues to raise.

The construction of the road cutting across Indian soil on the Aksai Chin plateau of Ladakh was known to the Indian ministries of Defense and External Affairs long before it was made public.

The Chinese incursions continued in the fifties in Garwal (Barahoti), Himachal Pradesh (Shipkila) and then spread to Ladakh and the NEFA (today Arunachal). Mao’s regime could have only been encouraged by the Government of India’s feeble complaints. Delhi was probably satisfied with its seasonal protests and the immediate denials from Beijing. Hundreds of such complaints have been recorded in the 14 volumes of the White Papers published from 1959 to 1968.

The Aksai Chin case

Soon after the PLA entered Lhasa, the Chinese made plans to improve communications and build new roads on a war-footing.40 The only way to consolidate and ‘unify’ the Empire was to construct a large network of roads. The work began immediately after the arrival of the first young Chinese soldiers in Lhasa. Priority was given to motorable roads: the Chamdo-Lhasa,41 the Qinghai-Lhasa42 and the Tibet-Xinjiang Highway (later known as the Aksai Chin) in western Tibet.

Tibet-Xinjiang Highway is still a bone of contention between India and China and the major hurdle in the ’stabilization of the border’.

The first surveys were done at the end of 1951 and construction probably began in 1952.

The official report of the 1962 China War prepared by the Indian Ministry of Defense43 gives a few examples showing that the construction of the road cutting across Indian soil on the Aksai Chin plateau of Ladakh was known to the Indian ministries of Defense and External Affairs long before it was made public.

The Official report mentions S.S. Khera, a Cabinet Secretary in 1962, who later wrote that “information about activities of the Chinese on the Indo-Tibetan border particularly in the Aksai Chin area had begun to come in by 1952 or earlier.”44

Tibet-Xinjiang Highway is still a bone of contention between India and China and the major hurdle in the “™stabilization of the border.

The Report further quotes the Director of Intelligence Bureau: “B.N. Mullik, who was then Director, Intelligence Bureau, has, however, claimed that he had been reporting about the road building activity of the Chinese in the area since as early as November 1952. According to BN Mullik, the Indian Trade Agent in Gartok also reported about it in July and September 1955, and August 1957.45

The different incidents which occurred in the early fifties should have awakened the Government of India from its soporific Hindi-Chini Bhai Bhai dream-like world. It was not to be so.

Instead of alarming Nehru, these disturbing reports reinforced his determination to bolster the friendship with China. The first of these incidents was the harassment of Jangpangi and his colleagues of the Trade Agency in Gartok. Though Nehru wrote to Zhou Enlai about it,46 no following action was taken and no proper analysis of Chinese motivations was made. Nehru barely brought the matter to Zhou’s notice: “Recently, some incidents have taken place when the local authorities in Tibet stopped our Trade Agent in Western Tibet from proceeding on his official tour to Rudok and his staff to Taklakot, both important trade marts for Indian traders and pilgrims. There has been a forcible seizure of his wireless set which is essential for the performance of his duties. We learnt of this incident with surprise and regret, because it did not seem to us in consonance with the friendly relations between our two countries…”47

The harassment of the Indian Trade Agent in Western Tibet was without doubt linked with the work which had started on the Tibet-Xinjiang highway. Rudok, located midway between Lhasa and Kashgar is the last small town before entering the Aksai Chin. The presence of an Indian official there was embarrassing for the Chinese. Did Nehru realise the implications of the incident or did he still believe in Chinese goodwill? It is difficult to say.

A telling incident

In September 1956, 20 Chinese crossed over the Shipki-la pass into Himachal Pradesh. A 27-member Border Security Force party met the Chinese the same day. The BSF were told by a Chinese officer that he was instructed to patrol right up to Hupsang Khad (4 miles south of Shipki-la, the acknowledged border pass under the Panchsheel Agreement). The BSF were however advised “to avoid an armed clash but not yield to the Chinese troops.”

Did Nehru realise the implications of the incident or did he still believe in Chinese goodwill?

Delhi did not know how to react. A few days later, Nehru wrote to the Foreign Secretary: “I agree with [your] suggestion…it would not be desirable for this question to be raised in the Lok Sabha at the present stage.”

The policy of the Indian government was to keep the matter quiet and eventually mention it ‘informally’ to the Chinese officials.

Finally, the MEA informed Beijing, “The Government of India are pained and surprised at this conduct of the Chinese commanding officer.”

This was fifty-five years ago.

Why was it not ‘desirable’ to raise in the Parliament the questions of intrusions ‘at the present stage’? The babus in the Ministry were probably confident that they would be able to solve the issue without informing the Indian public of the seriousness of the situation. We know the result of their confidence.

Is the situation different today?

Notes

- In particular ‘The Agreement Between the Government of the Republic of India and the Government of the People’s Republic of China on Confidence-Building Measures in the Military Field Along the Line of Actual Control in the India-China Border Areas‘ signed November 29, 1996.

- Or Agreement on Measures for the Peaceful Liberation of Tibet. It can be read on the author’s website: http://www.claudearpi.net/maintenance /uploaded_pics/1951Agreementon Measures forthePeacefulLiberationofTibet.pdf.

- Though the Chinese said Tibet was ‘liberated’.

- Agreement between The Republic of India and The People’s Republic of China on Trade and Intercourse between Tibet Region of China and India signed on April 29, 1954. Text available on: http://www.claudearpi.net/maintenance/uploaded_pics/ThePancheelAgreement.pdf.

- As compensation for surrendering India’s rights and privileges inherited from the Simla Convention (1914).

- Such a full-fledged mission in Lhasa, three trade marts, a garrison posted in Gyantse, a series of guest houses and the telegraph line to Lhasa.

- He however admitted that they were useful for trade.

- Selected Works of Jawaharlal Nehru (hereafter SWJN), Series II, Vol. 16-2. Letters to Chief Ministers, October 1951, p. 726.

- Starvation appeared for the first time in Tibet.

- SWJN, Series II, Vol. 18, Press conference of 21 June 1952, p. 471.

- Downgrading meant that Tibet had no more an independent foreign policy, the prerogative of an independent State and had therefore become a region (or province) of China.

- Ibid.

- SWJN, Series II, Vol. 18, Cable to Panikkar, June 16, 1952, p. 474.

- Press conference, New Delhi, 28 February 1952. Press Information Bureau.

- UP or United Provinces under the British Raj later became the State of Uttar Pradesh. Since 2000, the northern part of Uttar Pradesh has become the State of Uttarakhand.

- SWJN, Series II, Vol. 16 (2), Cable from Panikkar to Nehru, 28 September 1951, p. 643.

- SWJN, Series II, Vol. 16 (2), Talk with Loy Henderson, New Delhi. 15 September 1951, p. 627.

- This refers to the Aksai Chin area of Ladakh.

- SWJN, Series II, Vol. 16 (2), p. 541.

- The Central or State Government, the Survey of India, the Indian Trade Agent in Gartok or the Intelligence Bureau?

- Today, if a courageous historian requests the government to declassify this file, he will be quoted Article 8(1)(a) of the Right to Information Act: “there shall be no obligation to give any citizen, information, disclosure of which would prejudicially affect the sovereignty and integrity of India, the security, strategic, scientific or economic interests of the State”.

- In the NEFA.

- SWJN, Series II, Vol. 19. p. 651.

- Some Tibetans may have been ‘pushed’ by the Chinese into India territory to test the reactions of the Indian authorities. This is still regularly done in Arunachal and Ladakh were Tibetan herders are sent to graze into India.

- Mainly towards the frontier south of Tsona in NEFA, Chumbi Valley near Sikkim as well as Western Tibet (UP and Ladakh border).

- SWJN, Series II, Vol. 18, Desirability of Friendly Ties with China and Tibet, 12 April 1952, p. 471.

- SWJN, Series II, Vol. 21, Need for Check-Posts on U.P.-Tibet Border, MEA, 9 March 1953, p. 308.

- SWJN, Series II, Vol. 21, To K.N. Katju, February 13, 1953, p. 305.

- It is sad to note that the situation is not very different fifty-five years later.

- By that time, Mookerjee had died under mysterious circumstances in Srinagar.

- An Independent member from Andhra Pradesh.

- SWJN, Series II, Vol. 24, A Realistic Approach to Problems, p. 577.

- SWJN, Series II, Vol. 25, Principles of Foreign Policy, p. 391.

- Though by that time, Beijing was publishing maps engulfing part of Northern India in the Himalayas. Despite several Indian complaints, the maps were never withdrawn or modified.

- Barahoti (Wu-Je for the Chinese) is about one day’s journey from the Niti Pass.

- Ministry of External Affairs, Notes, Memoranda and Letters Exchanged and Agreements signed by the Governments of India and China, [known as White Papers] (New Delhi: Publication Division, 14 volumes, 1954-68), White Paper 1 (1954-59), Note given by the counsellor of China in India to the Ministry of External Affairs, 17 July 1954, p. 1.

- Ibid, p. 2.

- Kaul, T.N., Reminiscences Discreet and Indiscreet (New Delhi: Lancers Publishers, 1982), p. 104.

- Lall, John, Aksai Chin and the Sino-Indian Conflict (New Delhi: Allied Publishers, 1988), p. 240.

- One should not forget that in 1950 (when Eastern Tibet was invaded), a caravan took two months from the Chinese border to reach Lhasa, the Tibetan capital.

- Xinhua News Agency reported on 29 November 1954: “The two large armies of road builders from the eastern and western section of the Sikang-Tibet Highway joined hands on November 27. Sikang-Tibet Highway from Ya-an [capital of the now defunct province of Sikang] to Lhasa is now basically completed.” The communiqué further mentions that “gang builders and workers, including about 20,000 Tibetans, covered over 31,000 li on foot in the summer of 1953 and began construction of the 328 km of highway eastwards from Lhasa.”

- Three weeks later, another Chinese report stated: “The Tsinghai-Tibet Highway is now open to traffic. The first vehicles reached Lhasa on the afternoon of December 15. Over 2000 km long, the highway passes through Mongol, Tibetan, Hui and Khazak brother nationality districts, traverses 15 large mountains… crosses 25 rivers, grasslands and basins at an average elevation of over 4,000 meters above sea level.”

- A document still marked ‘restricted’ today, but fortunately available on Internet (on bharatrakshak.com in particular).

- Khera, S.S. India’s Defense Problem (Bombay, Orient Longmans, 1968), p. 157. Khera probably refers to Jangpandi’s reports.

- Mullik B.N., My Years with Nehru – The Chinese Betrayal (Delhi: Allied Publishers, 1971),

- pp. 196-97.

- On September 1, 1953, Nehru began his letter to the Chinese Premier thus: “It has been a matter of deep satisfaction to me to note the growing cooperation between our great countries in international affairs. I am convinced that this cooperation and friendship will not only be to our mutual advantage, but will also be a strong pillar for peace in Asia and the world”.

- SWJN, op. cit., Vol. 23, Cable to Zhou Enlai, September 1, 1953, p. 485.