“I ordered a second missile to be fired at her and after the second hit, her speed came down to zero and dense smoke started rising from the ship. She sank after about 45 minutes, approximately 35 miles south-southwest of Karachi. She had mistaken this to be an air attack and reported accordingly to Maritime Operations Room (MOR) Karachi, which perhaps resulted in the anti-aircraft guns in Karachi opening fire for a few minutes. The trajectories of these tracer shells were seen by us from seaward. KHAIBER’s VHF transmission to Karachi in plain language was picked up by our shore wireless stations due to anomalous propagation.

“The other large unidentified ship to the northeast was completely darkened and was proceeding at 16 knots. At about 2300 hrs, NIPAT was able to get her within range and fired the first missile which scored a hit. A second missile was fired soon after and when this hit the ship, I saw a huge flash going up to about twice the height of the ship. My inference at that time was that ammunition had exploded on board. The ship was seen on radar to have broken into two and she sank in less than eight minutes, about 26 miles south of Karachi. After the war, it was reliably learnt from merchant shipping circles and from Pakistan Navy officers who went over to Bangladesh, as well as from Military Attaches of foreign embassies in Pakistan that this ship had been carrying a near full load of US ammunition from Saigon, for the Pak Army and the Pak Air Force. Lloyds Register of Shipping, London, gave the name of the ship as MV VENUS CHALLENGER, a ship chartered by Pakistan, which had sailed from Saigon, called at Singapore en route and was due to arrive at Karachi at 0130 hrs, on 5 December 1971. In addition to the ship’s crew, the ship was reported to have had on board a small number of Pakistan naval officers and sailors for communication and ordnance duties.

I ordered a second missile to be fired at her and after the second hit, her speed came down to zero and dense smoke started rising from the ship.

“The Pak warship which I had detected at 1810 hrs on 4 December 1971, had obviously come down to rendezvous MV VENUS CHALLENGER and after satisfying herself that all was safe, she headed northwest at high speed towards Cape Monze.

“During their attacks, the missile boats NIRGHAT and NIPAT had moved ahead of the force by four to five miles. On completion of the attacks, they rejoined the force, which took them just about five minutes, as the rate of closing during the rejoining maneuver was 60 knots. This is the correct doctrine to be followed to prevent being fired at by ships of the own force.

“PNS SHAHJAHAN, a destroyer, was now ordered by MOR, Karachi, to proceed to the assistance of KHAIBER. But she regretted her inability to do S9, due to engine problems. Then PNS MUHAFIZ, an ocean going mine sweeper was detailed and she was approaching my Task Group from right ahead. I designated this target to missile boat VEER. The speed of advance of the Task Group was 28 knots and VEER was not able to do more than 29 knots at this time due to a minor engine problem. Since PNS MUHAFIZ had come well within the missile range, I ordered VEER to fire the missile at the Pak warship from inside the formation. VEER was just abaft my port beam when she fired the missile at about 2320 hrs. PNS MUHAFIZ was set on fire by this missile hit and was seen burning fiercely for over 70 minutes, and finally sank in that position, about 19 miles to the south of Karachi.

“The reported presence of a reconnaissance aircraft in the area caused undue concern in the mind of the Missile Boat Commander and the manifestation of this were two serious violations of the Operations Orders. One was that he fired a missile without orders at about 2330 hrs, towards the shore from a wrong position and in a wrong direction. I saw this missile travel to the westward of Karachi and hit the sea. When asked on VHF the reasons for firing this missile, there was no answer. Just then my navigating officer, requested me to come over to the display of the navigation radar in connection with the navigation to the predetermined position.

“It was reported to me that all the other ships of the group had disappeared from the radar display.

The reported presence of a reconnaissance aircraft in the area caused undue concern in the mind of the Missile Boat Commander and the manifestation of this were two serious violations of the Operations Orders.

“I altered the range scale of the navigation radar from 24 miles to 12 miles scale and noticed four small echoes about seven miles to the south of my ship. After repeated calls on VHF for about five minutes, the Missile Boat Commander replied that he was heading for the withdrawal point and at that moment, they were 12 miles to the south of KILTAN. The rate of opening between KILTAN and the other four ships was 60 knots i.e. a mile a minute. KATCHALL had also joined the missile boats in the ignominious retreat. KILT AN had not kept watch on VHF on the missile boat net as any spare capacity in communications was required to search and intercept enemy transmissions. This unauthorised withdrawal was the second and more serious violation of the Operations Orders by the Missile Boat Commander. If he was so obsessed by the need to withdraw, the only legitimate course of action open to him was to suggest that to me as the Task Group Commander. He had no authority whatsoever to withdraw on his own.

“Even if the reconnaissance aircraft were present, there was no necessity to flee from the area, as it would not have made much of a difference to the strike aircraft whether the ships were 20 miles or 40 miles from the coast, as the reconnaissance aircraft would be able to home the strike aircraft on to its target. In actual fact, as shown on KILTAN’s warning radar display, there was no reconnaissance aircraft airborne at all. Major General Fazal Muqeem Khan states that when the shore authorities in Karachi saw the glow from the burning MUHAFIZ, they sent a patrol boat to investigate. Had there been any reconnaissance aircraft airborne, it would have reported the incidents of dense smoke emanating from KHAIBER and the fiercely burning MUHAFIZ to MOR Karachi.

Withdrawal Phase

“After arrival in the predetermined position, KILTAN turned around at about 2355 hrs, 4 December 1971, and I saw the near perfect blackout in Karachi remaining intact.

“The other ships of the group were now about 16 miles to the south of KILT AN. After having performed the difficult task of transporting the missiles to the vicinity of Karachi and having sunk the enemy warships which tried to intercept’ us, we could have easily fired at least three missiles on shore targets. This excellent opportunity was wasted. At about 0100 hrs on 5 December, I sent the message ‘Angar’ to the C-in-C signifying the completion of Operation Trident.

If he was so obsessed by the need to withdraw, the only legitimate course of action open to him was to suggest that to me as the Task Group Commander. He had no authority whatsoever to withdraw on his own.

“Meanwhile, I had ascertained that KATCHALL, NIRGHAT and NIPAT were together but not in contact with VEER. At about 0045 ms, 5 December 1971, I gained radar contact with VEER at a range of 12 miles to the south of myself and established contact with her. VEER was able to do a speed of only 16 knots and her Estimated Time of Arrival (ETA) Withdrawal Point was 0115 hrs. I informed her that I was to her north and my ETA Withdrawal Point was 0200 hrs. I then passed the information about VEER to KATCHALL and the other two missile boats and directed them to proceed as per the withdrawal plan given in the Operations Orders. Due to the panic caused by the hasty withdrawal, VEER mistook KILTAN for an enemy warship and got a missile ready to fire at her. Fortunately, at that time VEER’s engines were repaired and she was able to regain her maximum speed. The Commanding Officer of VEER therefore decided not to fire the missile. This was revealed to me by the Commanding Officer of VEER, after my return to Bombay. After she regained her speed, VEER was also directed to proceed as per the withdrawal plan given in the Operations Orders.

“During the withdrawal phase, one gas turbine engine of KILTAN failed at about 0045 hrs. The second gas turbine engine also failed at about 0130 hrs. KILTAN was now running on her main diesel engine and her speed came down to 13 knots. KILTAN finally arrived at Mangrol at about 1800 hrs on 5 December 1971. All the other ships of the Task Group had already arrived there.

“After completion of refuelling when I wanted to sail the Task Group to Bombay, KILTAN’s diesel engine failed to start and she became immobile. I therefore detached KATCHALL and the three missile boats to proceed to Bombay, where they arrived on the evening of 6 December 1971. KILTAN stayed overnight at Mangrol and after getting one gas turbine engine operational by the morning of 6 December 1971 arrived in Bombay on the night of 7 December 1971.

“I called on the C-in-C on the afternoon of 8 December 1971 narrated the details of the Operation to him and handed over my report of the Operation. I also brought to his notice the serious violations of the Operations Order committed by K 25 due to which an excellent opportunity for attacking shore targets in Karachi was wasted.

“The Admiral stated that he was pleased that the primary task of sinking enemy warships had been accomplished. Since this was the first major operation undertaken by the Indian Navy since Independence he would rather condone the lapse of failing to attack shore targets in Karachi; any inquiry would attract adverse publicity to the Navy:’

In his book. Admiral Kohli states:

Had the command and control by CTG been more close and a plot maintained of friendlies and enemy contacts it might have been possible to achieve an even greater victory than was achieved

“It is quite obvious that a serious command and control problem engulfed the Trident force and could have led to serious difficulties:

- The escorts and boats had not worked together as a Task Group. There was no combined briefing. Understanding of each other by Commanding Officers which is born out of intimate knowledge of each other and their reactions under different conditions of stress was lacking.

- The limited Action Information Organisation facilities in the missile boats did not allow an adequate picture to be built up for the Command. This imposes a great burden on control of escorts and missile boats. The facilities for such command and control on Petyas were limited. But also the existing facilities were not used to best advantage.

- There were also some communication lapses. Those units who lost touch on VHF did not automatically come up on H/F resulting in loss of communication between ships of the force.

- Identification Friend or Foe between different types of ships and the compatibility of code numbers was not checked prior to commencement of the operation. It was subsequently established that they were different. In my opinion it was just as well that the attack was broken off by K 25.

- Had the command and control by CTG been more close and a plot maintained of friendlies and enemy contacts it might have been possible to achieve an even greater victory than was achieved.”

The Pakistan Navy’s Account of the First Missile Attack

The First Missile Attack

“The Story of the Pakistan Navy” has given a detailed account of the first missile attack on Karachi as seen from their end.

“On the morning of 4 December the three ships joined the flotilla and at 0700 KHAIBAR was despatched for the outer patrol. She arrived at the western edge of the patrol area at 1030 and commenced her patrol; the day remained uneventful. After darkness had set in. KHAIBAR intercepted an HF radio transmission at 1905 emanating from a south-easterly direction. This radio transmission could well have originated from the missile force.

“The attacking force was first picked up by the surveillance radar on Manora at 2010 more than two hours before the attack at the range of 75 miles to the south (bearing 165 degrees) of Karachi and tracked. Detection of the missile force more than an hour before it detected KHAIBAR and MUHAFIZ-which was not until 2130-by our shore radar station was a creditable performance. No better warning could be expected in the circumstances. The radar contact obtained by the shore station was reported to Maritime Headquarters as an unidentified contact approaching Karachi on a northerly course (345 degrees) at speed 20 knots.

“Another radar contact was detected at 2040 by the tracker radar at a range of 101 miles south of Karachi on a northerly course. Long ranges are possible under conditions of anomalous propagation of radio waves prevalent in winter months in this area. These radar detections led to the issue of a signal by NHQ at 2158 to ships at sea warning them of the presence of two groups of surface contacts approaching Karachi from the south. KHAIBAR was ordered to investigate these contacts but she never received the message.

“In KHAIBAR, a bright light was observed approaching from her starboard beam at 2245 when she was on a course of 125 degrees and her speed was 20 knots. Action stations were sounded immediately and the approaching missile thought to be an aircraft was engaged by Bofors guns. The first impression of the Commanding Officer soon after arrival on the bridge was that the bright white light was a flare dropped by an aircraft. But observing the speed of approach, he appreciated it to be an aircraft.

“The deadly missile struck KHAIBAR on the starboard side, below the aft galley in the Electricians messdeck at about 2245. The ship immediately lost propulsion and power and was plunged into darkness. A huge flame shot up in Number One Boiler Room and thick black smoke poured out of the funnel. When the fire was observed spreading towards the torpedo tubes, a sailor was sent to train the torpedo tubes and jettison the torpedoes. But the torpedo tubes were jammed in the fore and aft position and could not be moved.

No better warning could be expected in the circumstances.

“After the ship was hit, a message was immediately sent by hand of the Yeoman to the Radio Office for transmission to MHQ by means of the emergency transmitter. The voice pipe between the bridge and the Radio Office had been damaged and could not be used to pass the message. The message read: “Enemy aircraft attacked ship in position 020 FF 20. No 1 Boiler hit. Ship stopped”. The transmission of this message in total darkness and prevailing chaos, reflects creditably on the part of the staff. It was unfortunate that the position of the ship indicated in the message was incorrect; this caused considerable hardship to ship’s survivors later.

“It was after evaluation of the extensive damage, for the first time appreciated that the ship was hit by a missile. But no attempt was made to amend the previous signal to avoid delaying its transmission.

“A few minutes later, another missile was seen approaching the ship at about 2249 and was engaged by Bofors. The second missile, a few moments after it was sighted, hit No 2 Boiler Room on the starboard side. The ship, which till then had been on an even keel, began to list to port. The ship’s boats were shattered by the explosion. At 2300, it was decided to abandon ship when the list to port had become dangerous and the ship had become enveloped in uncontrollable fires. By 2315, it had been abandoned by all those who could leave the ship. More explosions, possibly of bursting of ammunition, continued to rock the ship as men jumped overboard from the sinking ship. The ship went down at about 2320 stern first with a heavy list to port.

The deadly missile struck KHAIBAR on the starboard side, below the aft galley in the Electricians messdeck at about 2245.

“MUHAFIZ had sailed on the evening of 4 December to relieve ZULFIQAR on the inner patrol in compliance with orders from the Task Force Commander. She arrived at her patrol area at 2245, just in time to witness the missile attack on KHAIBAR and to become a victim of the next. The trajectories of the two missiles fired at KHAIBAR were observed on board from MUHAFIZ plunging into the outer patrol area to her south. The wavering white lights, when first observed by the Commanding Officer, were thought to be star shells but later evaluated as aircraft-impressions which were very similar to those of Commanding Officer PNS KHAIBAR. It appears that none of those who saw the missiles that night recognised them as such.

“As MUHAFIZ altered course southward, the glow of light from the burning wreck of KHAIBAR could be seen on the horizon. Action stations were closed up as the ship headed towards the scene of action. She was on course 210 degrees, speed 9 knots, when at 2305, the third white light was observed heading straight for the ship. The fast approaching missile hit MUHAFIZ on the port side abaft the bridge. Upon being hit, the ship (which was of wooden construction) disintegrated instantly and some crew members were thrown into the water. The ship’s instantaneous collapse gave no time for the transmission of a distress message. The ship’s debris continued to burn for quite sometime while the survivors floated around the burning remains.

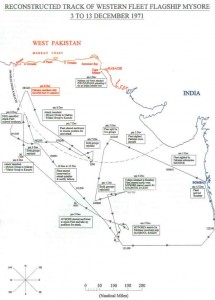

“The Indian Navy’s first missile attack on 4 December code-named Trident, was apparently planned well in advance and carefully rehearsed. It was based on the assumption that units of the PN Fleet would be on patrol some distance from Karachi at the outbreak of hostilities, and the assumption happened to be correct. The missile attack force consisted of two Petya class frigates, IN Ships TIR and KILTAN, and three Osa class missile boats, IN Ships NIPAT, NIRGHAT and VIR. The Trident force operated directly under the command of Vice Admiral Kohli, FOCINCWEST while the rest of the Western Fleet was placed separately under the command of FOCWEF. After topping up with fuel off Diu, the Trident force headed towards Dwarka keeping close to land in shallow waters to avoid PN submarines. Arriving off Dwarka, 150 miles from Karachi, the missile boats began their final approach on a direct route to Karachi at their maximum speed of 32 knots. A fourth missile boat was left at Dwarka to cover the withdrawal of the attacking force on its return passage.

It was unfortunate that the position of the ship indicated in the message was incorrect; this caused considerable hardship to ships survivors later.

“INS NIPAT’s radar apparently picked up two contacts, presumably KRAIBAR and MUHAFIZ, at 2130 at a range of about 40 miles, when the force was approximately 50 miles south of Karachi. NIPAT fired two missiles at KHAIBAR. INS NIRGHAT engaged MUHAFIZ from a range of about 20 miles. The missiles fired at Karachi harbour at 2330 were also from NIPAT. The oil installations had also been subjected to an aerial attack earlier in the day at 0830 when two oil tanks at Keamari had caught fire. The glow from the fire helped NIPAT as it approached Karachi harbour. Of the missiles fired by the Trident force, two hit KHAIBAR and one hit MUHAFIZ.

“Having launched their attacks, the Indian missile boats turned and headed for the R/V position off the coast of Mangrol where the tanker Poshak was waiting to refuel them. At this time TIPPU SULTAN, which was about 40 miles ahead of the formation picked up three radar contacts at a range of 49 miles. TIPPU SULTAN was on her Karachi bound passage to effect repairs to her main evaporator that had developed some defect the preceding day. FOFPAK on board BABUR on learning of the contacts by TIPPU SULTAN could do no more than take evasive action and move his force further inshore.

“Following their attack, two of the missile boats, VIR and NIPAT, suffered some mechanical failure. VIR was virtually disabled but managed to move at slow speed after effecting emergency repairs at sea. It is estimated that she went nearly 100 miles off her intended track in the process and NIPAT was also forced to reduce speed. By 0130, the latter could not have gone too far from Karachi and advantage could have been taken of the vulnerability of the two boats had the information available at MHQ been more precise.

“The missiles more than once had been mistaken for approaching aircraft. In fact, the attention of the controlling authorities ashore was distracted towards the threat of an aerial attack once too often to the extent that all warnings of a surface attack given by the tracker radar on Manora ware largely ignored or not given due weightage. Tracker radar was a good radar set loaned by SUPARCO to the Navy. Its performance was extremely good. It was installed in PNS Qasim near the entrance of the harbour.

“After the attack INS TIR (actually KATCHALL not TIR) and INS KILTAN, the two supporting Petyas, had been monitoring our signal traffic and were able to pick up MHQ message ordering SHAHJAHAN to assist KHAIBAR. This broadcast in plain language enabled the Indian Navy to announce the sinking of KHAIBAR the very next day. Fortunately, SHAHJAHAN was recalled and thus was saved. The Indian estimates of damage to SHAHJAHAN and sinking of two minesweepers and a merchant ship were exaggerated versions of the result of their missile attack.

”The rescue operation launched to locate and recover survivors of KRAIBAR was a somewhat disjointed and haphazard effort. The incorrect position of KHAIBAR indicated in her last signal also contributed towards the late recovery of survivors. The search effort was, therefore, centered on a position which was more than 20 miles away from the location where the ship had sunk. The location of survivors of MUHAFIZ was by chance.

“The credit for the rescue of survivors of KHAIBAR and MUHAFIZ goes to the gunboat SADAQAT whose single handed efforts saved many lives. It would be recalled that this boat, sent from Saudi Arabia and manned by a PN crew, was operating under the direct control of MHQ and had been employed on miscellaneous tasks. On the night of 4 December, soon after the attack on KRAIBAR, COMATRON in SADAQAT was ordered to proceed and look for KHAIBAR’s survivors.

“Soon after leaving harbour at about midnight, the Commanding Officer observed over the horizon a glow of light to the south-west. The light emanated from the burning remains of MUHAFIZ, but the fate of MUHAFIZ was not known to anyone at this time. He thought he had succeeded in locating KHAIBAR and steered for what he thought was the burning wreck of KHAIBAR.

“It was upon the recovery of survivors that it was for the first time learnt that MUHAFIZ had been sunk. The information was passed promptly to MHQ, and must have come as a shock for those who were busy organising the search for KHAIBAR and attempting to untangle the confused picture in the Headquarters. After an unsuccessful attempt to locate KHAIBAR’s survivors, the ship returned to harbour early on the morning of 5 December.

“ZULFIQAR joined the search effort at 0830 on 5 December, when she was on her way to join the Task Force having completed the inner patrol. At this time the Commanding Officer, having missed the original message, for the first time learnt the ship was required to conduct a search, but the message received merely stated that SHAHJAHAN was to join the Task Force while MADADGAR and ZULFIQAR were to continue the search. The Commanding Officer, not knowing the position or the purpose of search, joined MADADGAR which was seen emerging from the south of Churna Island at this time. Thus until the afternoon of 5 December, MADADGAR and ZULFIQAR had made no headway in the search for KIIWBAR’s survivors.

“COMATRON was again ordered to proceed out at 1000 to make a second attempt to locate KHAIBAR and her survivors. A fresh search centre was chosen by COMATRON and the search bore fruit when one of KIIWBAR’s life rafts with survivors on it was sighted at 1555. By 1745 on the evening of 5 December, the survivors were recovered. When it became dark, the ship set course for harbour and on the way back picked up 4 more survivors.

“In the meantime, a concerted search effort was mounted at 1425 when MHQ ordered COMKAR to ‘conduct a thorough search for survivors of KIWBAR’. A search force under the tactical command of COMMINRON in MUNSIF was despatched to the area. MADADGAR and ZULFIQAR joined MUNSIF for this search effort. An expanding square search based on a new search datum was commenced by the search force on arrival in the area towards the evening. This attempt was abandoned at 1913, when the search force was ordered to withdraw towards the coast, as a reaction to a false alarm of a missile attack. By this time the search had, in any case, become redundant as KIWBAR’s survivors had been picked up by the gunboat SADAQAT a few hours earlier.

“With the primacy of the missile threat recognised, a reappraisal of defence measures against this threat was done. It was obvious that the missile boats must be tackled at their base or during transit before they could launch their missiles. It was equally clear that this task could not be accomplished without the support of the PAF. The Navy had initially found it difficult to get firm commitments from the Air Force due to their involvement in Army operations. Once convinced of the necessity, after the missile attack on 4 December, the PAF responded by carrying out bombing raids over Okha harbour the forward base of missile boats. In one such attack, the fuelling facilities for missile boats at Okha were destroyed. The strikes would have been more effective had not the Indians, anticipating our reaction, dispersed the missile boats to less prominent locations along their coast.

“In the early hours of 6 December, afalse alarm of a missile attack was raised by the circulation of a number of reports indicating the presence of missile boats in the area west of Cape Monze. MHQ asked the PAF to carry out an air strike on a ship which had been identified as a missile boat by Naval observers flown on a Fokker Friendship aircraft for this specific task. ZUIFIQAR was informed by MHQ that a PAF sortie was on its way to attack a missile boat in the area. Shortly afterwards, at 0640, an aircraft appeared and strafed ZULFIQAR. The attack was broken off only when the ship’s frantic efforts to get herself identified as a friendly unit succeeded. There was a loss of lives and some were iryured. The ship sustained minor damage on the upper deck and returned to harbour to effect repairs and land casualties.”

In Retrospect

Viewed in retrospect, it is doubtful whether the first missile attack on Karachi could have achieved any more than it did because:

Viewed in retrospect, it is doubtful whether the first missile attack on Karachi could have achieved any more than it did because:

- The planning for such operations will always be highly classified, Earmarking forces beforehand and working them up for their tasks is likely to breach security. It is also not practical. Unforeseeable defects cause earmarked forces to fall out at the last minute, as happened in the subsequent attacks on Karachi when TALWAR on 6 December and KADMATT on 8 December fell out.

- The dispersal of friendly forces was unavoidable. When NIRGHAT found that KHAIBAR was approaching her at high speed, NIRGHAT had to reverse course to gain time to complete pre launch missile checks. In so doing she dropped miles astern of the other ships who were racing towards Karachi at high speed. NIRGHAT could never have caught up and arrived at the predetermined point during the time available.

Imponderables like these are unavoidable in naval operations. Overcoming them will depend on the reactions of the man on the spot.

As to who set the oil tanks on fire on 4 December. “The Story of the Pakistan Navy” clearly states that it was the Indian Air Force.

In its account of the first missile attack on 4 December, it states:

“The oil installations had also been subjected to an aerial attack earlier in the day at 0830 when two oil tanks at Keamari had caught fire.”

In its account of the second missile attack on 8 December it states:

“The first missile flew over the ships at the anchorage crossed Manora Island and crashed into an oil tank at the Keamari oil farm. There was a huge explosion and flames shot up so high that Qamar House-a multi-story building in the city- was clearly visible. The fire caused by the air attack on 4 December had been put out only a day earlier after three days of concerted efforts. Fires once again raged in the oilfarm after a short lived respite of a day. A distressing sight no doubt for everyone but particularly for those who had risked their lives in a tenacious battle against the oil farm fires earlier.”

1 India-trained Bangladesh Mukti Bahini HERO = 10 DARPOOK Pak Fouj.

1971 Bangladesh Liberation Struggle showed that Darpook Purkistan Army/ Air Force/ Navy morale would not stand more than a couple of hard blows at the right time and place.

Article was really great

I have also written on history of the Operation Trident 1971 and why 4th dec is celebrated as Navy day.

Let’s not bask in past glory. What’s important now, how India gonna take on Pakis and Chinks simultaneously. Congress has made Pakistan strong with nuclear weapons and made India weak against China by not building infrastructure in India-China border areas!

This is pure bullshit and propaganda spread by Pakistan by using Indian name for website.

Are pakistanis that dumb and idiots that on all 4 occassions they fired and sank their own warships ? do you guys think we are fools to believe your crap ?

It was the attack by Indian Naval vessels which destroyed karachi port and sank 4 paki vessels muhafiz , khaiber and challenger. why cant you shameless pakis accept it when the whole world knows how you guys lost the war and how your navy and airforce were humiliated and how your 1 lakh soilders n 20000 officers had to surrender to we Indians . wasnt that shameful enough that now you shameless pakis telling lies. a reminder you didnt win the war. we Indians won the war and f**ked you***

so how about the 6-day face to face battle in sep what happened then and i should remind u that we were just few miles away when indian begged for peace after disturbing it himself remember we gave you back half of india captured by our troops as a result of tashkant declration and the shameless indian soildiers we remember how they run leaving their shoes bare foot i think its enough i should not talk about how pak army fucked indian and american troops who were busy in supporting taliban and who were in tribal region spreading terrorism .we killed your men in operation zarbeazab thats why i see y your prime minister was jumping against this aperation.

The man that you killed was from where?

Who feeds you all these fictional story . . India can fuck you paki pigs anytime anywhere

India should be ashamed of that despite of being such a big country, 8 times bigger than Pakistan yet India could not fight the 1971 war alone as she rode on the shoulders of the USSR to fight with Pakistan because India was NOT capable to fight with Pakistan on the one-to-one basis, just because of the bitter experience of 1965 war when India attacked W. Pakistan suddenly at Lahore but was driven back beyond Amritsar. Pakistani forces were so fast that owing to the slow pace of supply they had to return from Amritsar, however, the infantry bought some Gifts from Amritsar for the people of Lahore and it was Cakes, pastries, and cookies from the bakery shops of Amritsar.

In 1971 war, the USSR had used AWACs on our borders which jammed our all radar systems, hence, GHQ and E.Command did not have contacts with each other.

Secondly, India had trained 300,000 Mukti Bahinis, the Indian Bengali terrorists, and infiltrated them in E.Pakistan because of which our army had to be divided and could not concentrate fully on borders.India taking advantage of it opened maximum fronts on E.pakistan borders which was covered from three sides by India.So, in such a situation, especially when a superpower was practically taking part with India, how a small country could have stayed longer.

Now India should know that in 2017 the things are very different and she could visualize the preparedness of our army that Pakistan had been attacked by the US and India in 2008 from Afghanistan, using Three armies, i.e TTP + NAA of Rashid Dostum + Indian army in civvies and they reached Swat, as per plan started making hue & cry that Taliban are just 60 miles away from Kahuta and Pakistan should handover all its nuclear arsenals to the US and all that blah blah blah. But our gallant army slaughtered all of them including Indian army in civvies, giving a BIG surprise to the world, particularly to the west.

And We are still alive and Kicking all the three armies continuously since then.

1971 Bangladesh Liberation Struggle showed that DARPUK P@rkistan Army/ Air Force/ Navy morale would not stand more than a couple of hard blows at the right time and place.