IDR Blog

Equality in Armed Forces Comes with All Its Dues: Revisiting the Judgement of Apex Court

“Inferior inducements bring second rate men. Second rate men invite second best security. In war there is no prize for the runner up.” —General Omar N Bradley

In what has been called significant judgment on gender equality, the Supreme Court on 16th February 2020 directed that Permanent Commission should be granted to women in army regardless of their service, in all the ten streams where the Union Government have already taken a decision to grant Short Service Commission to women[1].

The Court also held that absolute exclusion of women from command assignments is against Article 14 of the Constitution and unjustified. Therefore, the policy that women will be given only “staff appointments” was held to be unenforceable by the Court.

“An absolute bar on women seeking criteria or command appointments would not comport with the guarantee of equality under Article 14. Implicit in the guarantee of equality is that where the action of the State does differentiate between two classes of persons, it does not differentiate them in an unreasonable or irrational manner.”

To understand it in a better manner we need to quickly go through the history.

Historical Background

India has had women officers in its support services for over 70 years, with the Army Medical Corps (AMC) and the Military Nursing Service (MNS) taking the lead. These women from the AMC and MNS have been deployed even in “combat” zones, especially in Forward Hospitals and Field Hospitals in the Northern and Eastern sectors. Another major development came in 1993, when they were brought in for five years of service under “Special Entry Scheme”, which was then converted into Short Service Commission (SSC).

In 2008, permanent commission was extended to women in streams of Judge Advocate General (JAG) and Army Education Corps.

Last year, in a landmark move[2], the NarendraModi government decided to grant permanent commission to women in all ten branches where they are inducted for Short Service Commission — Signals, Engineers, Army Aviation, Army Air Defence, Electronics and Mechanical Engineers, Army Service Corps, Army Ordnance Corps and Intelligence[3].But it came with a caveat that women wouldn’t be considered for criteria and command appointments.

So this policy of considering women only for “staff appointments” and not for “criteria and command appointments” came under scrutiny before the apex court in Babita Puniya’s Case.

Revisiting the Issues and the Problem

The recent debate about the entry of women officers in the armed forces has been highly ill-informed and subjective in nature. People have taken stands and expressed opinion without analysing the matter in its entirety. It was imprudent on the part of Apex Court itself to consider it as an issue of equality of sexes or gender bias or even women’s liberation. It is also not a question of conquering the so-called ‘last male bastion’. That would amount to trifling a matter that concerns the well-being and the war-potential of a nation’s armed forces.

Focus need to be given on what General Bipin Rawat, then Chief of Army Staff (now Chief of Defence Staff), on December 15, 2018, in an interview to CNN-News 18, said-

“Women in combat would have to be “cocooned” from the prying eyes of subordinate soldiers; commanding officers of fighting units might require long maternity leave, which the army can ill afford; our soldiers are not ready to accept women leading them; and the society is not ready for women coming back in body bags.”

When the top most official of Army said this, then it definitely deserved consideration on merits keeping our emotions and passionate attitude aside.

In view of the same the present paper deals with the following issues:

• Whether it was right on the part of Apex Court to interfere with the policy of the Union and Defence Ministry, knowing the fact that Government is in best position to decide what will be in the interests of women as a person and nation as a whole after talking with the relevant stakeholders.

• Whether the policy of government differentiated in an arbitrary and unreasonable manner violating the concept of equality enshrined under Article 14.

• A detailed conclusion and

• Possible solution.

An Unwarranted Interference in Government’s Policy

A policy decision taken by the Government is not liable to interference[4], unless the Court is satisfied that the rule-making authority has acted arbitrarily or in violation of the fundamental right guaranteed under Articles 14 and 16[5].

The Supreme Court in Fertilizer Corpn. Kamgar Union (Regd.), Sindri v. Union of India[6], observed that:

…We certainly agree that judicial interference with the administration cannot be meticulous in our Montesquien system of separation of powers. The court cannot usurp or abdicate, and the parameters of judicial review must be clearly defined and never exceeded. This function is limited to testing whether the administrative action has been fair and free from the taint of unreasonableness and has substantially complied with the norms of procedure set for it by rules of public administration[7].

In Premium Granites v. State of T.N.[8], while considering the court’s powers in interfering with the policy decision, it was observed that:

It is not the domain of the Court to embark upon unchartered ocean of public policy in an exercise to consider as to whether a particular public policy is wise or a better public policy can be evolved. Such exercise must be left to the discretion of the executive and legislative authorities as the case may be.…[9]

Acceptance of this approach is reflected in the judgments of Laws LJ in International Transport Roth GmbH v. Secy. of State for the Home Department[10] and of Lord Nimmo Smith in Adams v. Lord Advocate[11] in which a distinction was drawn between areas where the subject-matter lies within the expertise of the courts (for instance, criminal justice, including sentencing and detention of individuals) and those which were more appropriate for decision by democratically elected and accountable bodies. If the courts step outside the area of their institutional competence, the government may react by getting Parliament to legislate to oust the jurisdiction of the courts altogether. Such a step would undermine the rule of law.

The Government, as was said in In re Permian Basin Area Rate cases[12], is entitled to make pragmatic adjustments which may be called for by particular circumstances. The court cannot strike down a policy decision taken by the State Government merely because it feels that another policy decision would have been fairer or wiser or more scientific or logical. The court can interfere only if the policy decision is patently arbitrary, discriminatory or mala fide.

Moreover in Babita Puniya’s Case Apex Court observed that:

“Courts are indeed conscious of the limitations which issues of national security and policy impose on the judicial evolution of doctrine in matters relating to the Armed forces.”

The court can interfere only if the policy decision is patently arbitrary, discriminatory or mala fide[13].It is against the background of these observations and keeping them in mind we will be dealing with second issue based on Article 14 of the Constitution.

Armed forces have been constituted with the sole purpose of ensuring defence of the country and all policy decisions should be guided by this overriding factor. All matters concerning defence of the country have to be considered in a dispassionate manner. No decision should be taken which even remotely affects the cohesiveness and efficiency of the military. Concern for equality of sexes or political expediency should not influence defence policies.

The wholesome rule in regard to judicial interference in administrative decisions is that if the Government takes into consideration all relevant factors, eschews from considering irrelevant factors and acts reasonably within the parameters of the law, courts would keep off the same[14].

Four categories of people are intimately connected with women’s presence in the services – Training academies, their commanding officers, colleague male officers and the soldiers. Their views and responses were seriously considered by the government while moulding policies to address all concerns because they are in the best position to tell what is in the interests of army and what is not. As they are in direct contact with the women officers and know the ground realities their views and perspective needs some mention here.

Training Academies Own Experiences

Compared to the average male Army recruit, the average female recruit is 4.8 inches shorter, weighs around 15 kg less, has 18 kg less muscle mass and 3.5 kg more fat mass. The consequence is that, in general, women are at a disadvantage when performing military tasks requiring muscular strength because of their lower muscle mass. Since fat mass is inversely related to aerobic capacity and heat tolerance, the average woman is also at a disadvantage when performing aerobic activities such as marching with heavy loads (related to the lower cardio respiratory capacity of women) and working in the heat[15].

While designing the training syllabus, this has been taken into account with different standards laid down for men and women.

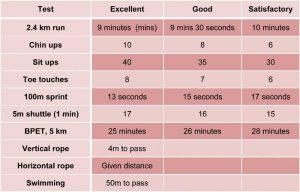

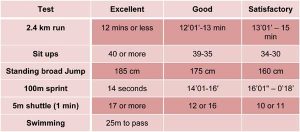

As of now, the physical differences between men and women are addressed in a very simplistic way during training by having separate standards for men and women. Even with the enforcement of separate standards, few women are able to achieve any high levels of physical fitness. The differences are exaggerated by theextremely modest standards adopted for women. For example, the basic Physical Efficiency Tests for a Gentlemen Cadet (GC) and a Lady Cadet at the Officers Training Academy (OTA) constitutes the following along with the timings.Only one chance at passing these tests is afforded to the GCs but passing these entire tests is at times discretionary for the women cadets.

As is evident that the most difficult test of endurance, the Battle Physical Efficiency Test (BPET) and other difficult tests such as, Chin-ups and Toe touches are also not applicable for lady cadets.

As it can be observed, there is a marked difference in the standards of men and women. During other training activities such as cross-country runs, route marches etc., women cover less than half the distance with half the weight as compared to men.

Boxing which is compulsory for every GC is a sport not even considered for women even if they pit against each other. Even in the informal physical toughening up sessions, most women are just not able to do the very basic and stock exercises at the Academy such as push-ups and front rolls and neither are they pushed to perform like the GCs who are pushed to the limit of their endurance.

Experiences at the training academies and research indicates a high risk of injury to female recruits with just over 50% injured during initial Army training compared to only 27% of males. The risk of leg injury to women was just over twice as likely and for stress fractures 4.71 times that of men. The higher risk of injury for women was related to a lower level of general fitness when compared to men. It was also reported that 54% of women sustained reportable injuries during Army basic training which resulted in an average loss of 13 days training time. Routinely, more women cadets report sick and are given excuse from PT or hospitalised.

These biological differences explain the male and female secondary sex characteristics which develop during puberty and have lifelong effects, including those most important for success in sports and military: categorically different strength, speed, and endurance[16].

As of now, the physical standards for women at the Academy are ridiculously low and any physically fit woman from any walk of life who has been exercising regularly can achieve them with ease. Over the years, physical standards have only marginally increased vis-a-vis men. There still exists a scope for greater improvement as can be made out from the tables and other details mentioned above. It would be unfair to solely censure women for accepting these low standards because that is all that they are made to do. Till the standards are toughened up to an extent where women as a group are perceived as physically tough, whether fair or not, they will never be judged as equals in the Academy.

As Capt. Deepanjali Bakshi (Retd.) remarks,in an ideal integrated situation, men and women should train together in all respects including physical training. But the vast differences in the prevailing physical standards have shown that under the current circumstances it is inconceivable for idealism and ground realities to connect. In the quest for total equality, if the exercise of similar standards is applied across-the-board, the results will be counter-productive. Either most women will not be able to cope with the rigours of physical training and suffer excessive injuries while trying to keep up with the men, or alternatively, if the standards are reduced to accommodate women, then men will not find training challenging enough[17].