IDR Blog

The Battle of Tawang

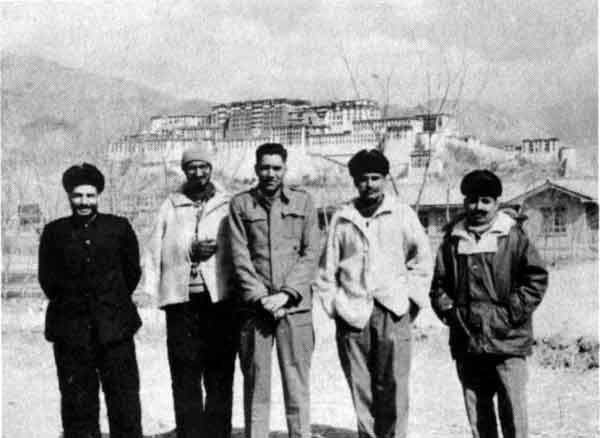

From Left to Right: Lt Col Rattan Singh, Lt Col Balwan S. Alhuwalia, Brig John Dalvi, Lt Col M.S. Rikh and Lt Col KK Tewari

Maj. Gen. K.K. Tewari, PVSM, AVSM (Retd) was commissioned in the British Indian Army in 1942. In 1962, he was Commander Signals of the 4 Infantry Division based in Tezpur, Assam. On October 20, 1962, as he was visiting his forward troops, the Chinese attacked India. He was taken prisoner and sent to Tibet where he stayed for nearly 7 months. He is today 90 years-old and lives in Auroville, South India. He spoke to Claude Arpi

As a result of the Chinese threat on our northern borders, sometime in 1959 the Headquarters of Eastern Command at Lucknow was given the operational responsibility for the defense of Sikkim and NEFA. I was at that time, the Commander Signals of the 4th (Red Eagle) Division Infantry Division located at Ambala. We were immediately ordered to move to Tezpur in Assam.

At that time, there were hardly any roads existing in any of the five frontier divisions (FD) of Arunachal Pradesh.

This Division, trained and equipped for fighting in the plains, had suddenly to be deployed to guard these high mountain regions. While a normal division occupies an area frontage of 30 to 40 km in the plains, we were assigned a front spreading on more than 1800 kilometers of mountainous terrain!

But worse! Before the Division could take its operational responsibilities to defend the border with Tibet, orders for the execution of an Operation Amar 2 were received from Lt Gen BM Kaul, then Quarter Master General in the Army HQ. We were suddenly supposed to build temporary basha (house with straw house) accommodations for the Division.

Besides the fact that my regiment had to provide communications for the Division in an entirely new and undeveloped area, we had now to become engineers and builders! You have to understand that a Signal Regiment is a functional unit in war or peace which is supposed to cater 24 hours a day to the various types of communications for its formation.

So, immediately after arrival in Tezpur, the Regiment got involved in the mad rush of building: the Prime Minister was to inaugurate the newly built bashas.

My first four months in command were a real nightmare. We would certainly have preferred to rough it out in tents and spend the time developing a reasonable communications set-up, getting our equipment properly checked and maintained and getting the men used to working with the available equipment in the mountains.

The idea was to establish the right of possession on our territory and to deter the Chinese from moving forward and occupying it, as was claimed by them.

It was a personal relief when, on 14 April 1960, the inauguration was over. Only then did we turn any serious attention and effort towards our operational responsibilities. Even our equipment was antiquated and unsuitable for mountainous terrain and the excessive ranges.

At that time, there were hardly any roads existing in any of the five frontier divisions (FD) of Arunachal Pradesh. The road into Kameng FD, the most vulnerable, finished at the Foothills just beyond Misamari [4 days walk from Tawang]

We were faced with shortages of every kind. It was during these early days in NEFA that one of the COs of an infantry battalion sent a note written on a chapatti. When asked for an explanation, he gave a classic reply: “Regret unorthodox stationary but atta (wheat flour) is the only commodity available for fighting, for feeding and for futile correspondence.”

Sometime in 1962, orders came from Army HQ for Operation Onkar (the famous “Forward Policy”), which directed all Assam Rifles posts to move forward, right up to the border. Of course, we were to back them. The idea was to establish the right of possession on our territory and to deter the Chinese from moving forward and occupying it, as was claimed by them. This order was certainly not supported by resources.

At that time, our Division had done almost three years non-family station service and some of the units were already on their way out on turnover. Suddenly all moves out of the area were cancelled and orders reversed.

Brig John Dalvi, the Commander Infantry Brigade who was in Tawang was ordered to move his HQ on a man/mule pack basis to Namka Chu River area. An ad hoc Brigade HQ was created for Tawang sector overnight with hardly any Signal resources.

At that time, I was the only field officer of Lt Col or higher rank who had the longest tenure at not only the divisional HQ but among all the divisional troops. I should have been posted out after a two-year tenure in a non-family station. But I had also a sort of premonition, and I recorded it in my diary, that a severe test was in the offing for me to assess my faith in the Divine. I certainly had no idea that I would be taken a prisoner of war.

At that time, I was the only field officer of Lt Col or higher rank who had the longest tenure at not only the divisional HQ but among all the divisional troops. I should have been posted out after a two-year tenure in a non-family station. But I had also a sort of premonition, and I recorded it in my diary, that a severe test was in the offing for me to assess my faith in the Divine. I certainly had no idea that I would be taken a prisoner of war.

On September 8, 1962, the Dhola post manned by the Assam Rifles on the McMahon line, was encircled by the Chinese. A few days later, we had a meeting of the senior commanders from the Army Commander downwards at Tezpur. A relief party had been ordered to relieve the besieged Dhola post. This linkup was expected by nightfall on the 14th of September: Everyone was tensely waiting for the news of the link-up. Naturally all eyes were on me; as the communications `chief’, to bring them the message. But there was no news until late in the evening.

After this incident, a new Corps HQ was created to take charge of operations in NEFA. Lt Gen B.M. Kaul was appointed as the Corps Commander. He arrived from Army HQ in a special aircraft at Tezpur in the late afternoon of 4 October. At about 10 pm, Lt Gen Kaul announced in his typical flamboyant style that he had taken over command of all troops in NEFA. It was all so dramatic!

Here was a new situation, normally a Corps HQ in those days would be served by a corps signal regiment and another communication zone signal regiment. These had yet to be raised.

To compound these difficulties, Lt Gen Kaul had his own way to send messages.

Normally, a signal message is supposed to be written in an abbreviated telegraphic language. But all messages from the new Corps Commander ran into a couple of typed sheets in prose language and were all marked Top Secret and Flash. They were not addressed to the next higher HQ but directly to Army HQ. You should understand that it required to stop all other traffic to clear FLASH messages.

In September 1962, the higher authorities had obviously assumed that it would be easy to beat the Chinese. Otherwise, one cannot imagine how such an order to engage the enemy could have been issued by Delhi to the ill-equipped, ill-clothed, ill-prepared, fatigued, disillusioned troops.

Do you realize that when Dalvi’s brigade arrived near the Namka Chu river after forced marches, he was ordered to throw the Chinese out of the Thagla ridge.

We filled up a jar of acid and marked prominently it: `Rum for Troops’…

I have to tell you a telling incident: arriving near the river, after an exhausting journey, the brigade signal officer discovered that the generating engine to charge the wireless batteries was not here. A porter had dropped the charging engine in a deep khud on the way. It could not be retrieved. I believe it was dropped deliberately, because some of these civilian porters were in the pay of the Chinese.

But I was in for a still bigger shock when it was discovered that almost all the secondary batteries had arrived without any acid. I presume that what had happened is that the porters must have found it lighter without liquid and they probably decided to lighten their loads by emptying out the acid from all the batteries.

How to establish communications when the batteries are dead and could not be recharged? Despite of our good relations with them, the Air Force helicopter boys refused to carry acid. There was no question, of course, of dropping sulphuric acid by air. What was I to do? Fate was also pushing me to my inevitable destiny.

We filled up a jar of acid and marked prominently it: `Rum for Troops’ and on October 18, I flew from Tezpur to Zimithang where I met with the GOC, Maj. Gen. Niranjan Prasad. Later, I went to Tsangdhar near the Namka chu in a two-seater Bell helicopter with just the pilot and with the `Rum’ jar strapped onto my lap. I landed there in the late afternoon and I marched down to Brig Dalvi’s brigade HQ.

I saw a line of khaki clad soldiers with a prominent red star on their uniforms advancing towards our bunker. I had never seen a Chinese soldier till then at such close range.

As I arrived there, I could quite clearly see the massing of the Chinese troops on the forward slopes of Thagla ridge.

When I discovered that every unit on the front had numerous signals problems, I decided to extend my stay by a day. It is where fate caught up with me!

On the 19th, Brig Dalvi informed over the telephone the GOC at Zimithang. He pleaded with his boss to let him move out of the `death trap’, up to a tactically sound defensive position. Brig Dalvi was told not to flap but to obey orders and stay put. He was extremely upset and passed the telephone to me saying, “You won’t believe me, Sir, but talk to your `bloody’ Commander Signals and he will tell you what all he can see with his naked eyes in front.”

I spoke to the GOC equally strongly saying that one could see the Chinese moving down the Thagla Ridge like ants and also see at least half a dozen mortars which were not even camouflaged. I added that the Chinese could not be there for a picnic. I was also told to concentrate on my work and not to worry.

I stayed on with the Gorkhas during the night of 19th October. Early on the 20th morning, I was woken up from a deep sleep by the noise of an intense bombardment. There was utter confusion in the pre-dawn darkness, shouting and yelling and running around in the midst of these exploding shells. I came out of the bunker and somehow found my way to the Signals bunker with two of my signalmen.

And suddenly hell was let loose with the Chinese yelling and firing and a number of them converging onto our bunker. My two assistants were killed and I was alive, but a PoW.

I looked out of the bunker. It was mystifying to see no visible movement outside. There was no one in sight. I peeped out of the bunker again. I saw a line of khaki clad soldiers with a prominent red star on their uniforms advancing towards our bunker. I had never seen a Chinese soldier till then at such close range.

I used to carry a 9 mm Browning automatic pistol in those days with one loaded clip.

The thought immediately was that one’s dead body should not be found with an unfired pistol; it must be used, however hopeless our situation. So, when a couple of Chinese soldiers approached our bunker, I let go the full clip at them. And suddenly hell was let loose with the Chinese yelling and firing and a number of them converging onto our bunker. My two assistants were killed and I was alive, but a PoW.

This book is an effort to recall the life in Kashmir, a state under perpetual conflict. It is a saga of courage, betrayal, passion and hatred seen from the eyes of a young soldier. Click to buy

In his book, Himalayan Blunder Brig. John Dalvi wrote: “Col. Tewari was a gentle, God-fearing man in addition to being a first rate signaler. He had worked against tremendous odds through the operations and had overcome difficulties which would have taxed an Army Signals Regiment. He is due much credit for providing communications with obsolete equipment and the distances involved. Instead of praise they came in for criticism for not being able to work miracles with out-dated sets and distances which were beyond the range of divisional signals”.”

Dalvi added: “There was a sad sequel to Tewari’s visit [on the Namkha chu]. …When the Gorkhas were attacked, Tewari found himself in the midst of an infantry battle. He was taken prisoner after the Chinese had over run the position. Who has ever heard of a Commander Signals being sent to an infantry battalion on the night before a massive attack, if there was any anticipation of a battle? He would have been at Divisional HQ attending to the Division’s communications.”

Post your Comment

8 thoughts on “The Battle of Tawang”

Loading Comments

Loading Comments

Sir I am tikili sahu …ap ke sath main service Kiya hu…my age 84 years

pl note Maj Gen K K Tiwari passed away 26th , sept at 1.45pm , on his feet while among friends ,

Mentality of Indian Army has been gradually change because of some of corrupted official from Indian Army. Today Army became more corrupted competitively to that of others official. Govt should react neutrally in this matter to save the nation

Kudos to our brave soldiers who fight valiantly in all conditions. It is there sheer courage and dedication that maintains the highest standards of the Indian Armed Forces. The political leadership even today is not free from the flaws that were responsible for the defeat at Namka Chu and perhaps will never be until they get compulsory military training.

Nobody talks abt liability of Nehru as PM and he never got punished for his day dreaming that always happened to be a blunder . nation suffered n he was awarded to Indians as Chacha Nehru. Shear democracy . No Liability clause.

sadness & anger wells up reading such, Every Time, at being ruled by IMBECILES & DUFFERS !

What the General Officer has written is absolutely true and I have also included it A in my 3770 page epic book NOTHING BUT! By Brigadier Samir Bhattacharya-Book Three –Chapter 15 A Forward Policy without Any Teeth and Chapter 17–Enticing the Chinese Dragon. All books from Book 1 to Book 6 available on amazon.in–barnes and noble—flipkart online book sites.

I salute your courage under fire sir, and all that you did then for safeguarding the country’s pride. I am now on page 50 of “The Himalayan Blunder”